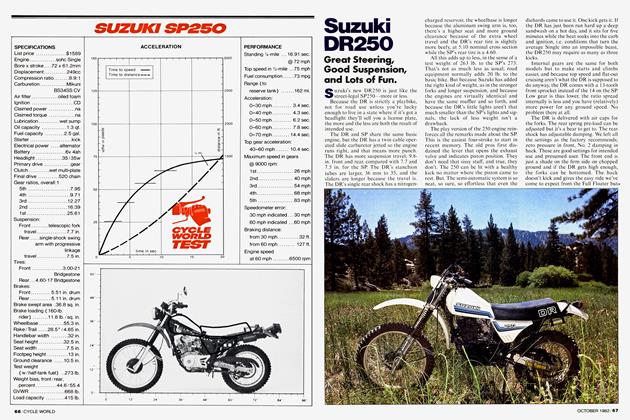

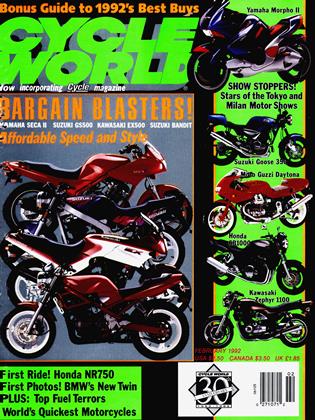

4. SUZUKI GS500E

SOMETHING OLD, SOMETHING NEW, SOMETHING PURPLE?

THE WORST THING ABOUT A comparison test is that there has to be a last-place finisher. And, in the case of the Suzuki GS500E, there could not be a more undeserved one. Because as bad as we feel about giving the Kawasaki EX500 third place, we feel even worse about giving the GS fourth. It earned a spot in our testers’ hearts as the underdog; one editor, in fact, threatened to elect it his favorite before sense—and a long, winding uphill road—prevailed.

Simply put, the GS lacks motor. With 1 ess displacement than the Seca, fewer cylinders than the Bandit and fewer valves than the EX, it was cursed from the start. Plus, its motor—a development of the two-valve per-cylinder, dohc, parallel-Twin of the ancient GS450E—is air-cooled. The poor thing never stood a chance.

On the dyno, the GS is down 8.5 horsepower to the EX, and 10 to the class-leading Seca. And though its tachometer is redlined at l 1,000 rpm, the engine peaks much lower—at about 8500. What this means is that to keep pace with the other bikes, the rider must ride the GS harder. So, it is a measure of the GS’s fine handling that, no matter which bikes our testers rode, the GS was always in the hunt. That wasn't the case during our dragstrip or top-speed testing, but on twisty mountain roads, the GS was able to keep up even when the pace quickened.

Most of the credit for the GS’s backroad performance goes to its rigid, twin-spar steel chassis, an item that would not look out of place on a modern sportbike. But some of the credit should also go to its suspension and tires. Although its fork and shock are lightly sprung and a bit underdamped in both directions, the GS’s suspension is well-balanced, and the bike remains composed at speed. Only mid-corner rough spots upset it. And its Bridgestone Exedra tires, a 110/70-17 front and 130/7017 rear, offer excellent traction, though hard riding accelerates wear rates. Our GS’s tires were showing signs of distress at 1000 miles.

Like the Bandit, the GS has excellent brakes, a single disc at each end offering more power than needed, considering the GS’s light, 390pound dry weight. And though all four of these bikes have 30-inch seat heights, give or take a few tenths, the GS is the shortest and the lightest. Those facts make the GS the easiest to maneuver at slow speeds.

What the GS lacks in outright performance, it makes up for in civility. Its smooth-running, torquey engine is easy to control, even for a novice. Its riding position is comfortable, with a low, wide tubular handlebar, low footpegs, and a nicely contoured, though thinly padded, seat. Cornering clearance, however, is not handicapped; only the Bandit had more.

If the GS500E still sold for its 1989 introductory price of $2999, it may have climbed a position in this comparison. But at $3249—while a few hundred dollars less expensive than any of the others—it does not offer enough savings to make up for its performance handicap.

But, while all four of these bikes will tolerate the abuse dealt them by novices, the GS is the most good-natured. It’s a Labrador Retriever on wheels. And if you’re on a budget, there may not be a better choice.

Suzuki

GS500

$3249

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSex Lessons

FEBRUARY 1992 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsBoots And Saddles

FEBRUARY 1992 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCThe Cannon Connection

FEBRUARY 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

FEBRUARY 1992 -

Roundup

RoundupAll-New Bmw Twin: Tradition Takes A Turn

FEBRUARY 1992 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki's Little Engine That Thinks Big

FEBRUARY 1992 By Yasushi Ichikawa