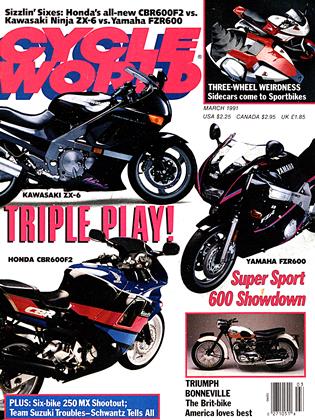

ATTACK OF THE SPORT-WORM!

EVER WANTED YOUR OWN GP-STYLE SI DEHACK?

JON F. THOMPSON

FORGET EVERYTHING YOU know about going straight. In fact, forget everything you know about riding a motorcycle, except maybe where the controls are. Just

try to remember, lane position’s real important. You wouldn’t want to prune the hack off on the undercarriage of some diesel, would you?"

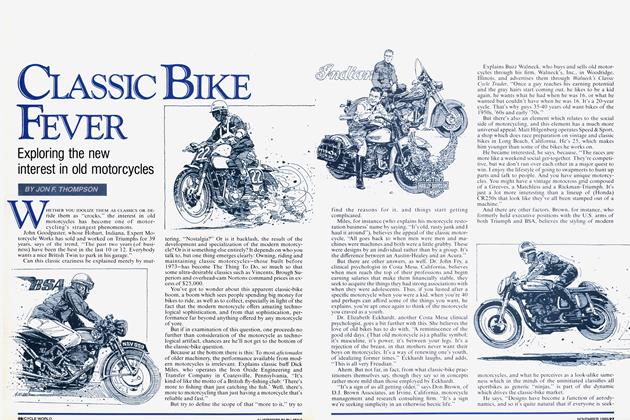

And with that. Associate Editor Brian Catterson. just back from a photo shoot with my mount, was gone. 1 was left standing in the CW garage next to a rather astonishing device. Call it a sidecar. Except that referring to the Side Bike Comanche as a sidecar is like referring to Eric Clapton as a guitarist or to Mario Andretti as a driver. For just as Clapton and Andretti are the creme de la creme of their respective arts, the Comanche is the ne plus ultra of sidecars.

Designed and built in France, the Comanche, and its less sporting, twoseat cousin, the Comete, have been available in the U.S. since mid-1990 through California Side Car (15161 Golden West Circle, Westminster, CA 92683; 714/891-1033). To get a Comanche or a Comete—they use identical frames, the only difference is the bodywork—all it takes is $8500 for the frame and gel-coated bodywork of the chair, $500 to paint the fiberglass, and $450 and two working days to mate the thing to your own Yamaha FJ 1 100 or FJ 1200, the only bikes the outfits are built for.

What you get for your money is something that will astound you and open your eyes about the joys of hacks. Especially sport-hacks.

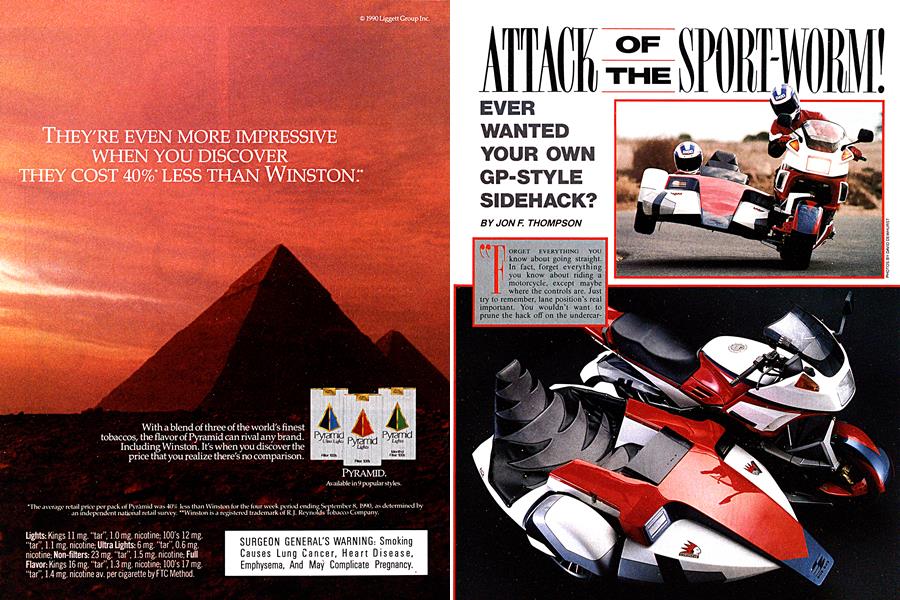

You'll also get looks. You'll get them from drivers, other motorcyclists. pedestrians, and cops. We certainly got our share. even when riding the dark blue and comparatively conventional Comete. But aboard the swoopy, red-and-white Comanche, heads swiveled, and adjacent traffic played bumpercars as drivers tried to get closer fora better look. Definitely not a ride for the shy.

Also, not a ride for the unadventurous, as the rig is an interesting blend of technologies and systems that are. at least in the U.S., fairly unusual, and use of which takes some getting used to.

Start right at the ground. The rig's underpinnings consist of a stout framework bolted securely to the FJ's frame in two spots on the right and one on the left. The resulting assembly rolls on three Dunlop automotive tires. Those on the front of the bike and the chair are 165/65-13s, with 1 75/65-14 rubber on the rear wheel.

Front suspension is pure hub-center, courtesy of a stout, beautifully fabricated steel steering frame and linkage, which feed their loads into two solid steel tubes clamped into the FJ's stock triple-clamps. An Ohlins shock takes care of the springing and damping. Rear suspension is stock Yamaha. An Ohlins unit also is used on the chair, and acts upon a pair of unequal-length control arms to provide the hack's suspension. What's important about that third wheel, the axis of which is just a little below and a little behind the bike's swingarmpivot point, is that it is linked, via a system of levers and rods, to the front axle, and therefore steers with the front wheel at a variable rate—with a little bit of steering on left-handers, and rather more of it on righthanders.

The rig's brake system is a modification of the standard FJ system, with some interesting additions. Gone are the FJ's two front rotors, but not its two calipers. These both work on one new rotor, mounted on the right side of the front wheel. Back brake is stock. The biggest addition is a Brembo rotor and caliper on the chair’s wheel, activated by the standard foot lever.

But if all this is interesting, so is the skin which shrouds the hard parts. Fiberglass from aftermarket companies sometimes can be less competently done than that from front-line, largevolume manufacturers who can afford to invest serious money into their tooling, but the Side Bike bodywork is straight, flat and ripple-free, and seems sufficiently heavy to withstand the stresses of normal use without ragging apart. Both rigs offer comfortable cockpits, the Comanche insisting that the passenger assume a position much like that of a formulacar driver, and the Comete allowing a more relaxed, upright riding position. The Comete offers one large, lockable storage trunk behind the passenger seat, while the racy Comanche bodywork contains four storage compartments—one each on either side of the knee well and one in front of the foot well. These are accessed by unlatching the sides of the front-hinged body flap and folding it up and open. The fourth compartment is behind the passenger backrest, behind the zip that helps hold the upholstery in place. Using all of them, there’s more than enough space to stow your goods for a long weekend away for yourself and a passenger.

We found two items of particular interest stowed in the Comanche’s front compartment. The first was a

tonneau for the hack, and the second w'as a tonneau for the hackee. The first was the usual, snap-down sort of cover, but the second was very special, as it has a heavy rubber rainsuit top built into it. Interesting, if just the slightest bit unusual.

But not as unusual as the sensations to be derived from riding the beast, as we learned to our considerable glee during CW*s time with the Side Bike creations. These sensations start the instant you throw your leg over the FJ chassis—and, yes, because of its sporting nature, we concentrated on the one hooked to the Comanche. Of course there’s no need for a centeror sidestand. And of course, once aboard, there’s no need, ever, for the rider to remove his feet from the bike's pegs. Why should he? The thing isn’t going to fall over.

At rest, the bike feels like a motorcycle, but once you've adjusted the right-side mirror so you can see the

looks of terror on your unwitting passenger's face, engaged first and released the clutch, it's a lot more like a giant, 100-horse ATV, one that doesn't exactly want to go straightjust as Catterson suggested —but which doesn't exactly want to turn, either, at least not using the procedures normally associated with turning a motorcycle.

The thing will turn, though, and do so w’ith vigor. You’ve just got to get the dynamics figured out. a task complicated by the fact that those dynamics change, depending on whether you're turning left, or right, with power on, or off. and whether you're doing so without a passenger, or with one.

Unloaded, sans monkey, first: Screw the power on. hard, and the rig wants to go right. Roll out, tap the front brake, it wants to go left. Roll out, tap the front brake and hit the rear brake, it wants to go right. For this reason, and because stopping distances for the rig, with its claimed 783-pound dry weight, were considerably longer than with the bare FJ, we found ourselves leaving plenty of room in which to get slowed.

Up to speed, in a straight line, the rig hunts and twitches, and reacts to the slightest input to the handlebar as instantly as a spark from static electricity. Want to change lanes? Just turn your head a few degrees; the change in your shoulders’ attitude is enough to put you into the next lane right now. We should point out that the two-passenger Comete is less twitchy, and. after a few miles on either rig, a rider learns to relax more and let the outfit have its head.

As corners heave into view, so do the first of your real learning experiences. You tip-toe around righthanders, channeling all your body weight into the right side of the chassis by shifting emphasis to the right footpeg, this to help keep the chair's wheel on the pavement. Flying the chair's wheel is fun. and certainly astounds passers-by. It also astounds traffic cops, and probably that’s not so good. Also, when you fly the third wheeh you lose its steering, and that’s even less good.

On left-handers, no tip-toeing is necessary. You just rail, power on, through your curve, relishing the effect of the chair’s outrigger-like third wheel. Some care is called for, though, because in left-handers, the chassis wants to push, or understeer, and the harder you screw the power on, the more it pushes, as the FJ’s prodigious torque acts to lighten the weight on the front tire. Rolling out changes things in a hurry, transferring weight off the back and onto the front, and snapping the chassis around into oversteer. Fun to play with, once you figure out how to deal with it.

With a passenger in the chair, things change considerably, and if acceleration is slowed a bit because of the passenger's extra weight added to the 250 pounds of empty chair, cornering speeds generally go up as the monkey learns how to use his weight. With a rider aboard, righthanders become a lot more fun. thanks to the extra ballast. The chair, in fact, is designed with cutouts that encourage the passenger to shift weight, especially on right-handers, just like a GP sidecar monkey. Lefts, meanwhile, become rather more difficult. As you screw the power on in exits from left-handers, with a passenger aboard, it becomes especially important to stand on the FJ’s pegs and place as much weight as possible on the handlebars to try and keep the front tire on the pavement. Without doing that, the rig just wants to push straight ahead.

What’s of interest is that whether you’re carrying a passenger or not, left and right corners require different techniques. For lefts, you charge in as hard as the rig’s weird braking will allow, apex late, and screw on the gas. For right-handers, a much more deliberate, classic, geometric cornering arc, with no quick direction changes, is called for.

Great fun, and worth the effort it takes to get past the initial intimidation factor of a machine this unusual.

A few things we didn't much care for about the Side Bike include the difficulty of checking the FJ's oil level in the engine's sight glass—for this, we resorted to contortions, a small makeup mirror, and a flashlight—and the buzziness of the FJ itself. thanks to its solidly mounted en-

gine and the lower final-drive ratio derived from the smaller-than-stock rear tire. This raised the revs at cruising speeds from about 3800 rpm at 60 mph on a standard FJ to more like 4350 rpm. Hauling the rig's extra weight around also impacted fuel mileage—no big deal for its own sake, but important for the loss of range it implies. Ridden hard, the Comanche-equipped FJ delivered fuel economy in the midto high-20-mpg range, cutting the overall range to about 160 miles from the bike’s ability to cover, unadorned by sidehack, 2 l 5 miles between fill-ups.

How fast is the Comanche, bottom-line? Not as fast as a good rider on a solo FJ, not in a straight line and not around any corner of either direction. But that’s not a fair comparison. The rig is much easier to ride at the limit than a bare FJ. because its limits are lower, and it’s easier to deal with, once its limits are exceeded and it starts to get out of shape, than any motorcycle we can think of. As a purely practical device—well, forget it; we’ll take our pickup trucks, thanks just the same. But for a completely unique way to have a ball, to experience the sensations felt by GP sidecar riders, and to operate a vehicle nobody else in your neighborhood is going to have a copy of, well, the Side Bike Comanche has to be the ride of choice. E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontNote To Edgar

March 1991 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeFuture Shock

March 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsShould You Buy An Italian Bike?

March 1991 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1991 -

Roundup

RoundupAnother Yamaha We Can't Have

March 1991 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupLaverda Gsx-R: Italy's Orient Express

March 1991 By Alan Cathcart