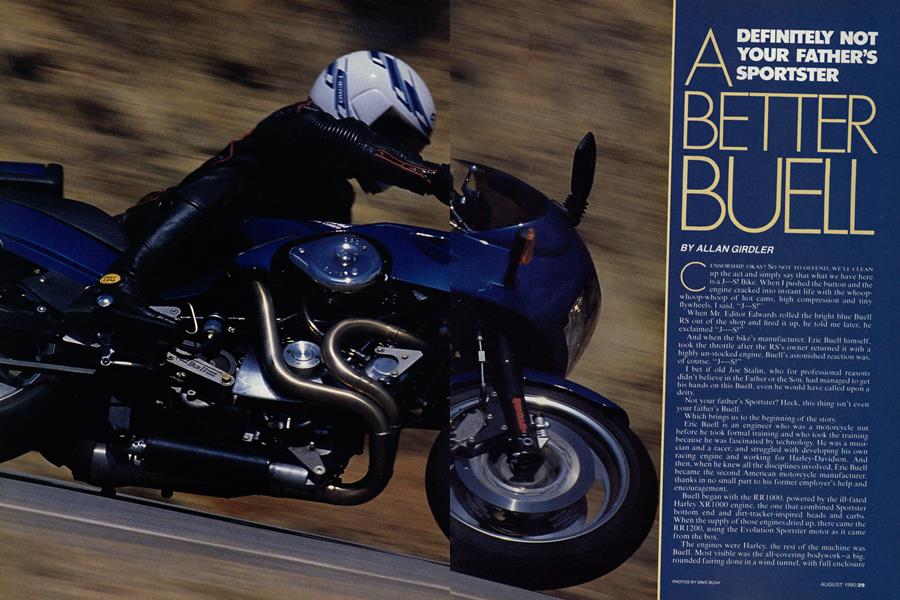

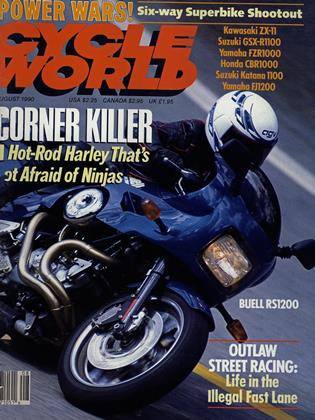

DEFINITELY NOT YOUR FATHER’S SPORTSTER

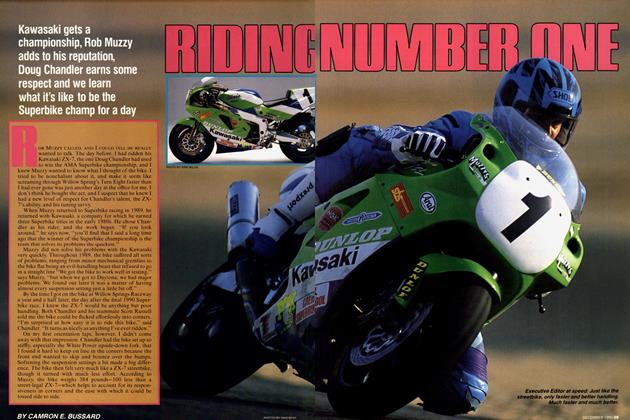

A BETTER BUELL

CENSORSHIP, OKAY? So NOT TO OFFEND, WE'LL CLEAN up the act and simply say that what we have here is a J---S! Bike. When I pushed the button and the engine cracked into instant life with the whoop-whoop-whoop of hot cams, high compression and tiny flywheels, I said, J---S!"

When Mr. Editor Edwards rolled the bright blue Buell RS out of the shop and fired it up, he told me later, he exclaimed "J---S!"

And when the bike's manufacturer, Eric Buell himself, took the throttle after the RS's owner returned it with a highly un-stocked engine, Buell's astonished reaction was, of course, "J---S!"

l bet if old Joe Stalin, who for professional reasons c ïdn t believe in the Father or the Son, had managed to «el his hands on this Buell, even he would have called upon a deity. r

Not your father’s Sportster? Heck, this thina isn’t even your father's Buell.

W hich brings us to the beginning of the story.

Erie Buell is an engineer who was a motorcycle nut before he took formal training and who took the training because he was fascinated by technology. Fie was a musician and a racer, and struggled with developing his own racing engine and working for Harley-Davidson. And then, when he knew all the disciplines involved, Eric Buell became the second American motorcycle manufacturer, thanks in no small part to his former employer's help and encouragement. ' 1

BueM Kaan with the RR 1000. powered by the ill-fated Harley XR1000 engine, the one that combined Sportster bottom end and dirt-tracker-inspired heads and carbs.

D D^nne suPP,y,oi those engines dried up. there came the RR I _()(). using the Evolution Sportster motor as it came from the box.

Ehe engines were Harley, the rest of the machine was Buell. Most visible was the all-covering bodywork—a big. ounded fairing done in a w ind tunnel, with full enclosure 2for the engine, and bulbous panels for seat, rear fender and hindquarters.

The RR models were full race: demanding seating position, solo seat, limited steering lock; exactly what s demanded by the sort of people who’ll pay the money required for new technology.

Which is exactly what Buells had, and still have. Notable here is Buell’s patented engine-mounting system,

which he calls Uniplanar. , , nn thf>

This is different. Begin with the rear wheel on the ground. The swingarm attaches to the wheel, and the engine/transmission unit goes onto the other end of the fwingarm. Atop the engine is the frame a network of straight steel tubing. The car chaps would call it a space frame. Buell says it’s geodesic, from the dictionary

“light, straight structure." . , , _ ,

Now then: The engine isn't really inside the frame, and the rear wheel doesn’t directly attach to the frame. Instead, the engine is the key structural member. The swingarm moves in one plane, up and down. It can t go back and forth and it can’t twist or move side to side^The engi and frame are connected by three rubber-insulated mounts and four Heim-jointed rods, geometrically sited so the engine can move-make that shake only up an down. In one plane, see, which is where Uniplanar comes from. The mounting system isn t like Harley s rubber mounts, nor like the design Norton used. It is, to belabor the obvious, unique, as proven by the patent. And while the Harley V-Twin vibrates a lot, because the cylinders are aligned fore and aft and the connecting rods ditto the vibration is in the plane in which the engine is allowed to

m(presto The first impression is that the Harley XLH engine now runs smoothly. Of course, it doesn’t. Instead, just as shutting the door makes the lawn mower sound quieter, the mounting system isolates the rider (and the bike s vanous hardware) from the vibration the engine is bound by naThe rest of the bike is merely the best Buell can get.

There’s a Works Performance rear shock, mounted below the engine in a protective sort of canister, and there are 41mm Marzocchi fork tubes, beefy and fitted with Buell own anti-dive system and with Buell’s own brakes fourpiston discs. It’s worth noting here that as the Buell factory grows, Buell uses more and more of his own pieces, made in his shops or produced elsewhere to his specifications. This is beginning to make economic sense and. of course, one of the reasons the man is in business for himself is to do things the way he believes they should be done.

By mid-1990, Buell had made something close to 200 examples of his art. They’ve gone to enthusiasts in the U.S., Europe and, yes, Japan. No secret has been made of the Harley-Davidson involvement, and in other countries, the Harley half is as much a lure as the sportbike half.

But the market for sporting single-seaters is finite, and Buell reckons it’s taken just about all the RR 1200s the world wants, which gets us to the model here, the RS.

Buell’s racing background and reading of the market led first to the RRs. Yet, he knew—and was told many times in case he didn’t know—that there are enthusiasts who don’t want full enclosure, who like to see mechanical parts, and who’d sometimes like to take their Significant Other along for the ride.

Buell could understand this and deal with it. The resulting RS has the same frame, engine-mounting system, brakes and suspension as the RR. but there’s a half-fairing instead of a full one, there are places through which one can view the machinery, and the seat is now long enough for two.

Beyond that, there’s another unique feature, a fold-up backrest/storage bin. In his youth, Buell says, he once inadvertently wheelied a girl off the back of his streetbike. He’s never forgotten that, so when market forces dictated passenger space, Buell designed a hinge and catch for the bodywork behind the operator. Lock it down and it braces the rider, like a racebike seat cowl. Lock it up and it supports the passenger, like a sissy bar. Further, the shape lends itself to carrying small packages: Remove the velcroed-on upholstery and there's a fine place to stow, for example, the uneaten pasta from lunch, which was enjoyed at an Italian restaurant, what with this motorcycle being a Yankee version of a Bimota.

■ The J—S! element referred to earlier comes from a happy accident. With no criticism meant, the Buell frame and chassis and body and brakes, etc., are way beyond the demands put on them by the stock XLH engine. The 1200cc Evo Sportster is friendly and durable, but it comes with 55 horsepower, and that isn't enough to put the rest of the package to a test.

Comes now Don McCaw, a magna cum laude engineer in Iowa with his own engine business and a passion for doing things like going 200 miles per hour at Bonneville. Working on his own, for the sport of it, McCaw bought a Buell RS from his neighborhood Harley-Davidson dealer and enlisted the cooperation of George Smith at S&S, one of the places to buy speed for Harleys.

McCaw’s engine uses S&S Sidewinder aluminum barrels with steel bores of 3.63 inches and a stock stroke, which boosts the 1200 out to 1 340cc, or 80 cubic inches, as we old guys say. The heads were reworked by Craig Walters, a Spokane, Washington, wizard. The lighter flywheels are from S&S, as is the carburetor and the connecting rods. The latter are fractionally longer than stock, to give what McCaw figures is a better ratio of rod/stroke length. The heads and forged aluminum pistons are machined to allow for the extra reach, and compression ratio is 9.8:1, about as high as today’s gas will allow.

S&S also supplied aluminum pushrods and prototype lifters, which McCaw hedges about, saying only that they’re hydraulic at low rpm, and quiet, and go to solid at high revs, which allows more timing precision,and just how this is done he’d rather not say right now. Cams are from Thundertech. The exhaust system is Supertrapp, as used on stock Buells, but reworked here to match the cams. Dyna supplied the ignition,and the clutch is from Barnett, with Harley’s Screamin' Eagle springs.

McCaw is more of an engine builder than he is motorcyele owner, so the $6500 engine in this $ 14,695 motorcycle was delivered to Cycle World fresh, with instructions to break it in carefully and then run it as hard as we pleased.

That’s exactly what we did.

The numbers we tallied back up seat-of-the-pants expletives. Run to its 7200-rpm redline (stock is 5500), McCaw’s Buell reeled off a 138-mph top-speed pass. At the strip, it notched an 11.46-second run at 119.04. Those numbers make the bike easily the quickest, fastest streetlegal Harley ever to compress our eyeballs. But its top-gear roll-ons were even more astonishing, helped, no doubt, by the bike's light. 485-pound dry weight. Impressive enough was the 40-to-60-mph time of 3.75 seconds, but 60-to-80 flashed by in just 2.75 seconds-and that, folk^s 9uickIn fact no CWtest bike, not even the awesome ZX-1 l,has ever posted a quicker time than this built-up Buell

McCaw says actual power isn’t something he likes to claim, no two dynamometers being alike, but estimates that the engine probably has between 100 and 115 horsepower at the engine sprocket. It fired quickly from cold okay 60-degrees-in-the-shop cold-didn t idle worth beans, but whipped out instant power, as much as we could possibly want, at a crack of the throttle. McCaw says it will last as long as a stocker if you ride it like a stocker, as long as a racer if you use it that way, and what else is new. In sum the engine is a tribute to its designers and to its

modifiers.

So is the Buell, in its own way.

Eric Buell isn’t much for compromise. Further, he must know that he isn’t selling motorcycles, not in the sense that Honda and Harley sell machines for transportation and fun to people with budgets and other demands on their

time and energy. , , -,

And he’s sport-oriented, a roadracer at heart, so it

shouldn't leave you slack-jawed that the RS has two elements in which it’s at home. One is the winding, climbing, sweeping open road we all dream of. At speeds that put the engine and gears and brakes and suspension to work, the RS works. The fairing shields the torso from the blast. I he steering is quick and sure. There’s always more power than you can use and the brakes make you glad for the pads on the back of the fairing that literally keep you from being

pitched into the screen. Handling? Not quite world-class, as the pull-to-compress shock has some wonkiness left in it, and the Marzocchi fork is very good, but not great. Still, this bike, with this engine and a respectable pilot at the controls will hang with anything that Japan, Italy or Germany can throw its way. r ,,

The other element is public display. None of us would even think about the simple pleasure of having the sharpest baddest bike in the parking lot, heck no. But tor academic reasons, suffice it that the Buell knocks em out.

The downside to the RS is that for three or four times the price of a Sportster, it isn’t as good as a stock XLH in daily life. The seating is cramped and the saddle is good for only about an hour unless adrenaline masks the discomfort. Steering lock is limited. The suspension that works well at speed, pounds kidneys on the interstate. There are quirks like not being able to zero the odometer at fill-ups. And there are awkward bits, like the fiber flap to keep the rider's right heel out of the chain, or the footpegs that look like refugees from a swap-meet parts bin.

The Buell RS isn’t a Sportster with bodywork. It’s not a Harley-Davidson with a souped-up engine. The Buell has

a distinct character, a personality, as much a sports VTwin in its own way as is a Moto Guzzi or (Dare we say? Yes!) a Ducati.

In a rational world, we wouldn’t even consider paying more for a motorcycle we can use less.

In a rational world, Eric Buell would spend his time working with a committee somewhere, earning his pension. Instead, if this is the morning, he’s at the shop. If it’s the afternoon, he’s at home minding his small children and working on CAD-CAM programs for his next bike.

If you believe in motorcycles, clap your hands. SI

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

August 1990 -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

August 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

August 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

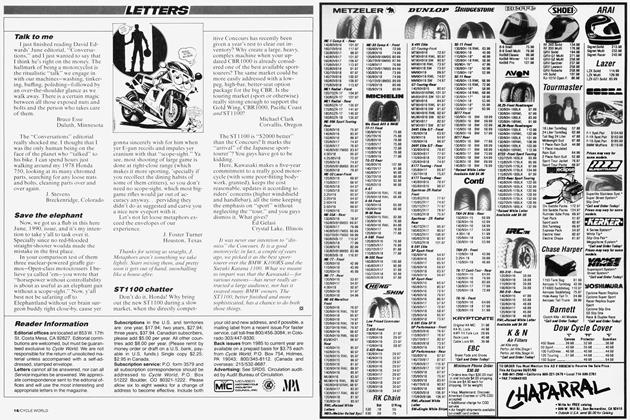

LettersLetters

August 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupBimota-Guzzi: High-Tech Chassis Meets Low-Tech Motor

August 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupHonda Prices: What Was Up Goes Down

August 1990 By Jon F. Thompson