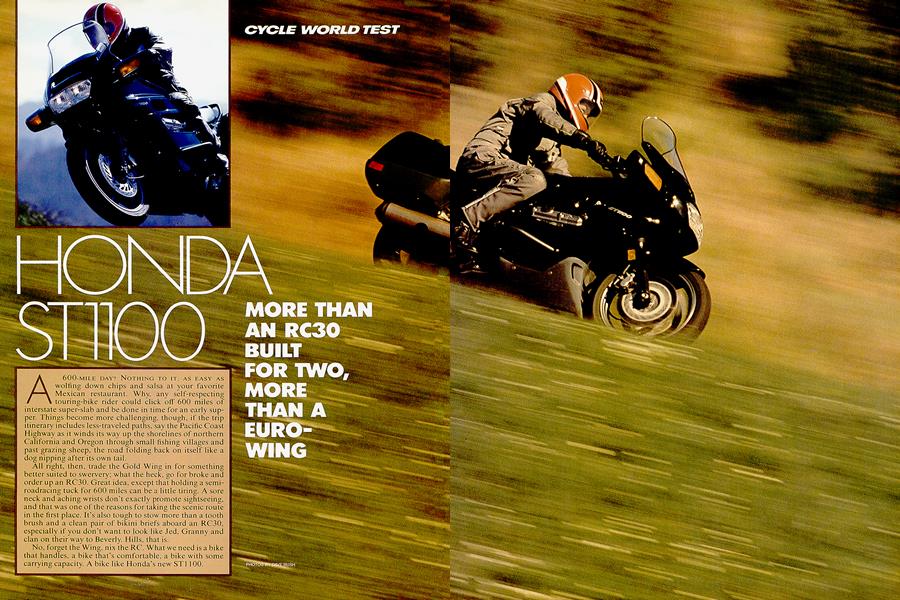

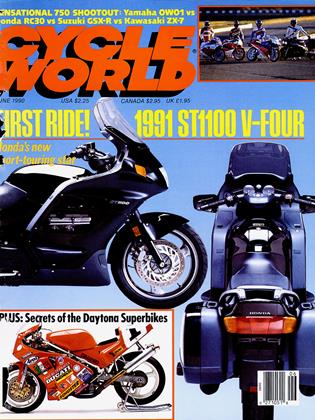

HONDA ST1100

CYCLE WORLD TEST

MORE THAN AN RC30 BUILT FOR TEO, MORE THAN A EUROWING

A 600-MILE DAY? NOTHING TO IT; AS EASY AS wolfing down chips and salsa at your favorite Mexican restaurant. Why, any self-respecting touring-bike rider could click off 600 miles of interstate super-slab and be done in time for an early supper. Things become more challenging, though, if the trip itinerary includes less-traveled paths, say the Pacific Coast Highway as it winds its way up the shorelines of northern California and Oregon through small fishing villages and past grazing sheep, the road folding back on itself like a dog nipping after its own tail.

All right, then, trade the Gold Wing in for something better suited to swervery; what the heck, go for broke and order up an RC30. Great idea, except that holding a semiroadracing tuck for 600 miles can be a little tiring. A sore neck and aching wrists don’t exactly promote sightseeing, and that was one of the reasons for taking the scenic route in the first place. It’s also tough to stow more than a tooth brush and a clean pair of bikini briefs aboard an RC30, especially if you don’t want to look like Jed. Granny and clan on their way to Beverly. Hills, that is.

No, forget the Wing, nix the RC. What we need is a bike that handles, a bike that’s comfortable, a bike with some carrying capacity. A bike like Honda’s new STI 100.

Sport-touring bikes have never really caught on in America. A small throng swears by BMW’s RS series, and Kawasaki’s Concours has a loyal following, though the bike sold poorly enough in 1987 and ’88 that Kawasaki called for a one-year hiatus in production before cranking up the assembly lines again this year. In the past, there was Honda’s CBX Six with a half-fairing and bowling-bagsized panniers, a bike that proved as popular then as embassy duty in the Middle East is today.

Given sport-tourers less than warm embrace by the majority of U.S. riders, it shouldn’t come as a shock that the ST is primarily a European motorcycle. In fact, the idea for the bike was conceived by Honda Germany, and the project continued as the first joint effort of Honda Japan

and Honda Europe. Sport-touring bikes make good sense in Europe, where a Gold Wing just feels clumsy and is barely fast enough on the autobahns to stay out of the bumpers of swift-running Mercs and Bimmers. And, yes, any 600cc-and-above sportbike is fast enough for the highways and handles well enough for the mountain passes Over There, but European necks and wrists aren’t any less susceptible to cricks than ours, and, if anything, European riders heap more gear on bikes then we do.

So, Europeans get the ST l 100 (and an additional moniker for the bike, “Pan-European”), and we in the U.S. are given another chance to take a sport-tourer to heart.

There’s nothing earth-shattering about this new motorcycle’s chassis. The ST’s frame is made of mild steel, and :

apart from tubes slightly larger in diameter than normal and some unusual curves around the engine, students of frame-making will find little else noteworthy here.

Likewise, no new ground is broken by the ST 1100’s suspension. The fork has 41mm stanchion tubes and is non-adjustable. A cartridge damper contained in the right fork leg and an anti-dive mechanism in the left at least keep the front suspension out of the Stone Age. Rear suspension is handled by a single shock, adjustable for spring preload and rebound damping. Like the system used by BMW, the Honda’s shock is located on the right side of the bike and connects the swingarm and frame directly, without benefit of a rising-rate linkage system. As on BMWs, the ST’s swingarm contains the bike’s drive shaft, but it has two conventional arms rather than being single-sided as are the swingarms used on the German machines. The 1100 also makes do without the Paralever anti-chassisjacking mechanism that is used to good effect on the R100GS and the new K1.

The bodywork that wraps around the ST l 100’s running gear shows that Honda learned from the criticisms that were leveled against the Kawasaki Concours’ wavy, poorly fitting panels. The ST’s multi-piece fairing fits together well, and the cockpit surfaces are nicely finished in a pebble-grain pattern. The bike’s removable saddlebags, each of which will easily swallow a full-face helmet, are well integrated into the bike’s lines.

Opinions on the ST’s appearance varied wildly. Many observers, particularly non-motorcycle enthusiasts, were bowled over by the bike, using words like “beautiful,” “refined” and “classy.” The more involved in the sport a person was, the less enthusiastic his view of the ST tended to be. More than one rider referred to the bike as looking like a “Pacific Coast on hormones,” and there was the Ninja 900 rider who trailed the ST for a few blocks before pulling alongside, pointing at the Honda and then wigwagging his outstretched hand in the universal symbol of so-so-ness.

During our 2500 miles with the ST, any lukewarm feelings about its looks by test riders were nullified soon after the reviewer climbed aboard the bike and set off for the next gas stop. “Great engine,” was the universal acclaim as soon as the helmet came off at the other end. And indeed it is.

The ST continues Honda’s fascination with V-Four powerplants, but this time, there’s a difference. Instead of the now-familiar across-the-frame disposition of the crankshaft as exhibited in Honda’s Interceptor, Sabre and Magna series, the ST engine has been swung around 90 degrees so that its crank runs fore and aft, and its cylinder banks angle out to the sides. This is the same configuration as Moto Guzzi’s Twins and Honda’s own now-defunct CX500 and CX650 push-rod Twins. And, in fact, when the CX500 was introduced in 1978, there were rumors that two of the engines would be linked together to form a longitudinal V-Four.

Twelve years later, the 90-degree, liquid-cooled V-Four mostly hidden behind the ST’s plastic panels shows some automotive influence, as well. With its car-like valve covers, complete with an oil-filler cap that might well have been lifted from a Civic or Accord, visible through the gilled side panels, it would be easy to believe that the engineers in the Honda’s car division had as much to do with the engine’s design as the bike guys did.

That theory is further supported by the ST’s timing belt, a toothed rubber affair that winds its way over various cogs and pulleys at the front of the engine, just as many cars’ timing belts do. But there’s some new thinking going on here. Rather than loop the timing belt over a gear on the end of each cylinder assembly’s two overhead camshafts, a configuration that adds height to an engine, Honda’s engineers devised a set-up where the belt drives a gearset situated between and slightly below the cams. Thus, the ST uses belt-actuated, gear-driven camshafts.

Of course, all of this engineering acumen, which has resulted in the application for 14 patents covering the engine, wouldn’t be worth a warm cup of used 20w-40 if the motor didn’t work out on the road, which it does. Thumb the engine into life and it quickly settles into a 1 200-rpm idle, accompanied by a gear whine that’s reminiscent of the noise made by BMW’s threeand four-cylinder Kbikes. The whine is soon drowned out by the flat exhaust note of the V-Four. The ST has a 360-degree crankshaft, but unlike some earlier Honda V-Fours that used a 360degree crank and had powerbands about as exciting as elevator music, the new engine has some personality. One rider likened the motor to BMW’s lOOOcc opposed-Twin, albeit one that had been eating its Wheaties and working out three times a week.

Performance-wise, the ST is no quicker or faster than its chief rivals, the K 1OORS and Concours. Where the Honda has an advantage is in its tall gearing. At 60 miles per hour, notching from fourth gear up to fifth drops the revs from 3700 to just over 3000, a Harley-like level that is 500 to 600 rpm lower than the competition. This Iong-leggedness is accompanied by almost-vibrationless running at the speeds that most American riders will encounter. Thanks for this go to the V-Four layout—inherently smoother than an inline-Four—plus a counterbalancer and rubbermounted handlebar and footpegs. Zing the tach to it’s 8000-rpm redline and some quaking can be felt in the footpegs and seat, but the mirrors remain as clear as cable television no matter what rpm the engine is spinning.

The ST1 100’s suspension compliments the engine’s big strides, soaking up most jolts before they can do any damage to the rider. We found that setting the rear shock to its fourth (of five) spring-preload position and screwing the damping adjuster one-half turn short of maximum matched the fork’s action nicely and got rid of a weaving in fast corners that was evident with the shock on its softest settings. Still, some riders felt the lack of front-fork adjustability and the rear suspension’s lack of a rising-rate linkage system hurt the bike in fast cornering, noting a vagueness in the front end and the inability of the shock to deal with sharp bumps at high speed. It can be argued that a $9000 flagship sport-tourer ($2200 more than the Concours, about $3000 less than the yet-to-be-released 1990 K100RS) ought to come with more sophisticated suspension.

Be that as it may, it should be noted that the ST1 100, a bike with comparatively lazy frame geometry, an 18-inch front wheel and a dry weight of 658 pounds, was ridden from Portland, Oregon, to Los Angeles in the company of the four 750cc sportbikes tested elsewhere in this issue. On unfamiliar roads, the ST, unsophisticated suspension and all, gave a good account of itself, dogging four of the besthandling motorcycles on Earth, only losing ground when the cornering elevated to wham-bam, knee-skimming velocities.

And the ST is blessed with comfort that no repli-racer can match. Fairly wide, tubular handlebars rise three inches, allowing a sporting but comfortable stance. The stepped seat will allow about 250 miles of the bike’s 300mile range to be used without numbing the rider’s derrière, at which point the fuel-reserve light is on and its time to look for gas anyway. Wind protection is excellent for riders 5 foot 10 and below, though taller riders complained of buffeting, especially at high speeds.

In the end, the ST will win friends not on any single virtue, but on the combination of its likable engine, its competent handling and its well-thought-out features. No, it’s not a Gold Wing born in Europe. It’s not an RC30 built for two, nor is it an Oriental BMW. Think of the ST 1 100 as the arrival, at last, of the Japanese sport-tourer.

EDITORS' NOTES

A SPORT-TOURING MOTORCYCLE FITS my street-riding desires perfectly. I've enjoyed riding BMW's sporttourers over the years, and I bought one of the first Kawasaki Concours. So, Honda's new sport-touring model quickly grabbed my attention. And after riding the ST1100 for several hundred miles along the California and Oregon coasts, I'm even more excited: Its V-Four engine is smooth, powerful, responsive and flexible, and its suspension provides a plush ride while droning along at normal touring speeds, and does a respectable job of keeping the bike stable when the road sprouts curves. The handlebar is just the right height. shape and reach for me, but the ST1 100's otherwise nicely padded seat lets me slide forward into the back of the fuel tank under hard braking.

That glitch wouldn't stop me from buying an ST. but the bike's retail price of $8998 would probably bring a gasp from my wife. I think after a couple of rides, she can be convinced. -Ron Griewe, Senior Editor

I'VE BEEN WAITING FOR SOMEONE TO come out with the. ultimate sporttouring motorcycle for quite some time. I appreciate BMW's idiosyn cratic machines, and Kawasaki's Concours was a great attempt. but I want something more refined. Some thing like Honda's new ST 1100. The ST's secret lies in its whopping I 11%... ) I %./~ II'..~ I1 VV 1085cc V-Four engine. This baby steams, especially in its~ low and mid, range. I like the upright seating position and the wide handlebar that allows me to click off miles effortlessly, all the while being protected from the ele ments by the large windscreen and fairing. The detach~ able luggage is a bit small, but it's better than having to bungee and strap bags all over the bike.

Don't get me wrong. even a motorcycle as good as the ST is not my ultimate sport-touring machine. It's a bit too big and heavy for that. But it comes real close.

-Camron E. Bussard, Executive Editor

OFFICER BARDER OF THE OREGON State Troopers didn't have much to say about the STI 100's sophisti cated, integrated appearance. I ex plained that the Honda had been bred for the autobahns of Germany. and that it had such a torquey, tall geared motor that I really had no choice but to rundown his section of U.S. 101 at 80 miles per hour, especially since road con ditions were good and traffic was light. He wasn't buying any of it, and kindly invited me to contribute $ 1 72 to the state's coffers.

Had Officer Barder been a little more lenient, i'd have told him how much I liked the ST. How I thought the ST was at least $2000 better than Kawasaki's Concours. How it's preferable to the BMW sport-tourers I've rid den. I'd even have told him that as impressive as it is, the ST is in need of a few options. I'd like to see a flatter seat offered. A radio/cassette player would be nice. Maybe a cruise control.

And definitely a radar detector.

-David Edwards, Editor ]

HONDA ST1100

$8998

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

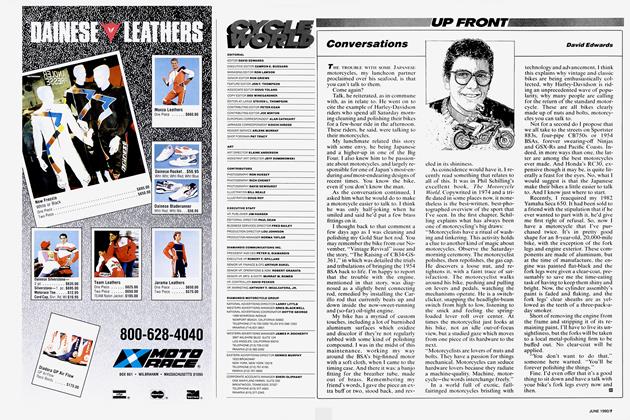

Up Front

Up FrontConversations

June 1990 By David Edwards -

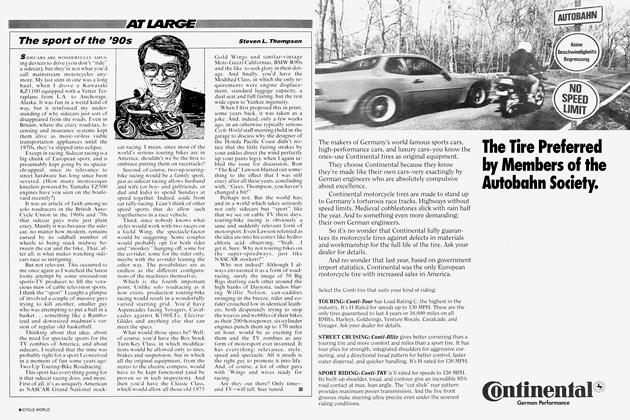

At Large

At LargeThe Sport of the '90s

June 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

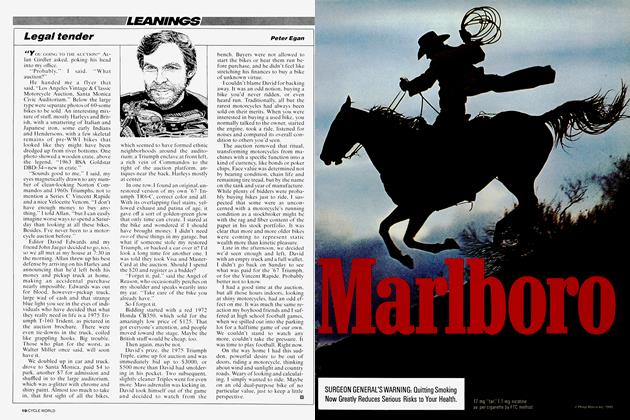

Leanings

LeaningsLegal Tender

June 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupBrm Spyder Upgrading the Gsx-R1 100's Flash Factor

June 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

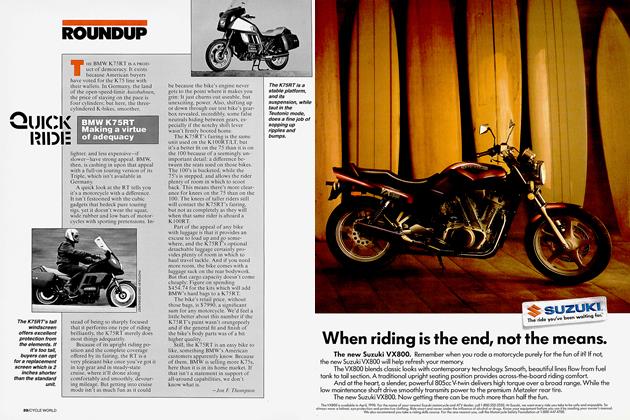

Roundup

RoundupBmw K75rt Making A Virtue of Adequacy

June 1990 By Jon F. Thompson