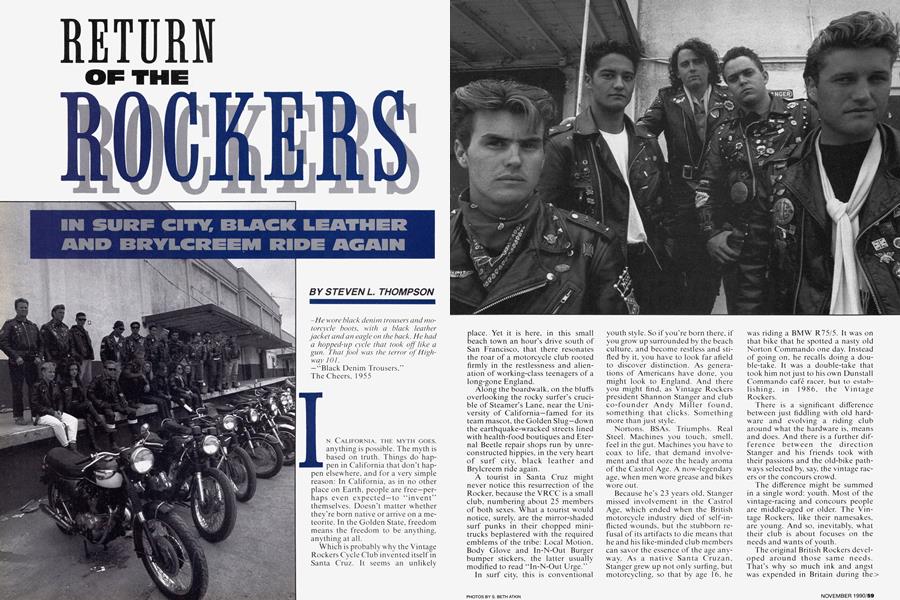

RETURN OF THE ROCKERS

IN SURF CITY, BLACK LEATHER AND BRYLCREEM RIDE AGAIN

STEVEN L. THOMPSON

He wore black denim trousers and motorcycle boots, with a black leather jacket and an eagle on the back. He had a hopped-up cycle that took off like a gun. That fool was the terror of Highway 101.

—“Black Denim Trousers,”

The Cheers, 1955

IN CALIFORNIA, THE MYTH GOES, anything is possible. The myth is based on truth. Things do happen in California that don't happen elsewhere, and for a very simple reason: In California, as in no other place on Earth, people are free—perhaps even expected—to "invent" themselves. Doesn't matter whether they're born native or arrive on a meteorite. In the Golden State, freedom means the freedom to be anything, anything at all.

Which is probably why the Vintage Rockers Cycle Club invented itself in Santa Cruz. It seems an unlikely place. Yet it is here, in this small beach town an hour’s drive south of San Francisco, that there resonates the roar of a motorcycle club rooted firmly in the restlessness and alienation of working-class teenagers of a long-gone England.

Along the boardwalk, on the bluffs overlooking the rocky surfer’s crucible of Steamer’s Lane, near the University of California—famed for its team mascot, the Golden Slug—down the earthquake-wracked streets lined with health-food boutiques and Eternal Beetle repair shops run by unreconstructed hippies, in the very heart of surf city, black leather and Brylcreem ride again.

A tourist in Santa Cruz might never notice this resurrection of the Rocker, because the VRCC is a small club, numbering about 25 members of both sexes. What a tourist would notice, surely, are the mirror-shaded surf punks in their chopped minitrucks beplastered with the required emblems of the tribe: Local Motion, Body Glove and In-N-Out Burger bumper stickers, the latter usually modified to read “In-N-Out Urge.”

In surf city, this is conventional youth style. So if you’re born there, if you grow up surrounded by the beach culture, and become restless and stifled by it, you have to look far afield to discover distinction. As generations of Americans have done, you might look to England. And there you might find, as Vintage Rockers president Shannon Stanger and club co-founder Andy Miller found, something that clicks. Something more than just style.

Nortons. BSAs. Triumphs. Real Steel. Machines you touch, smell, feel in the gut. Machines you have to coax to life, that demand involvement and that ooze the heady aroma of the Castrol Age. A now-legendary age, when men wore grease and bikes wore out.

Because he’s 23 years old, Stanger missed involvement in the Castrol Age, which ended when the British motorcycle industry died of self-inflicted wounds, but the stubborn refusal of its artifacts to die means that he and his like-minded club members can savor the essence of the age anyway. As a native Santa Cruzan, Stanger grew up not only surfing, but motorcycling, so that by age 16, he was riding a BMW R75/5. It was on that bike that he spotted a nasty old Norton Commando one day. Instead of going on, he recalls doing a double-take. It was a double-take that took him not just to his own Dunstall Commando café racer, but to establishing, in 1986, the Vintage Rockers.

There is a significant difference between just fiddling with old hardware and evolving a riding club around what the hardware is, means and does. And there is a further difference between the direction Stanger and his friends took with their passions and the old-bike pathways selected by, say, the vintage racers or the concours crowd.

The difference might be summed in a single word: youth. Most of the vintage-racing and concours people are middle-aged or older. The Vintage Rockers, like their namesakes, are young. And so, inevitably, what their club is about focuses on the needs and wants of youth.

The original British Rockers developed around those same needs. That’s why so much ink and angst was expended in Britain during the> 1950s and ’60s to dissect the Rocker phenomenon. It baffled, enraged and sometimes frightened the adult citizens of England. At the root of it all was the fear not really of caféracer motorcycles, but of the exploding power of youth “out of control.” Youth in loosely organized clubs like the Rockers.

The Rocker phenomenon itself has generated considerable social history (such as the two titles offered by Motorbooks International: Rockers! by Johnny Stuart and Café Racers: Rockers, Rock n'Roll and the Coffee Bar Cult, by Mike Clay), and the impact of the movement is once again rippling through English life with the emergence of Retro-Rockers. Now in their middle age, these once-and-future Rockers gather annually on London’s Chelsea Bridge to fire up old bikes, don old jackets and rekindle old flames.

All of which is of some interest to the young (median age, 21 ) members of the Vintage Rockers. But only some interest. These riders are not simply celebrating another age’s style and values so much as using them to enhance and enliven their own lives. Mostly through the efforts of club president Stanger, they have codifed the core values of what they think it means to be an American Rocker.

During the '50s and ’60s, many people in England thought that one of the core values was a propensity for violence. Former Rockers like Fair Spares America manager Phil Radford—now fortysomething and living and working in San Jose, California, but originally from Nottingham—reluctantly admit that fighting, mostly with the Vespa-riding Mods, was a part of the scene. But he stresses the same things that Stanger and his club members do about why Rockers stick together: Fundamentally, it’s the British concept of “mate-ship.” >

As both chroniclers listed above agree, what glued Rockers together in England was, in the words of the Rocker in Quadrophenia, The Who’s 1979 saga of the Mods-and-Rockers 1964 battle in Brighton, “not (just) the bikes, the people.” The impecunious condition of most young working-class people kept them on fairly short tethers, so that the local coffee bars and transport cafés became havens from the psychological oppression and physical compression of the tiny council-house “estates” in which many had grown up.

It was at these hangouts (like the famous Ace Café) that kids searching for freedom from the depressing future of what author Stuart calls “squirrel-cage” working-class jobs, as well as the ruthless conformist pressures of the contemporary adult world, invented their own cultures. One was what would become the Rockers. (Originally, they called themselves Bike Boys or Ton-Up Boys, not Rockers.) And the fundamental value at the heart of Rockerdom was mate-ship.

Americans have no direct equivalent of mate-ship, but in British youth cultures, one’s mates are more than just friends; they are the cornerstones of one’s identity, aspirations and status. So what Shannon Stanger stresses now about his club is that it’s much more to its members than merely a means by which they display a certain fashion; it’s the joy of Real Steel ridership and all that goes with it, as well as a transmogrified American version of mate-ship.

Because most of the Vintage Rockers are from Santa Cruz or nearby, they share experiences, mores and values beyond black leather, tattoos and bikes. Thus the idea of mate-ship can work for them. Whether they're going to nearby Cabrillo College (like Sarah), digging as archaeologists at Indian sites (like Brian and John), working at places like Sears (like Stanger), Plam BMW (where Stanger once worked, and where club secretary Chris Canterbury now works as parts manager), or “doing hair” as Moto Guzzi rider Angel does, the Vintage Rockers cohere socially. Membership is controlled by the group, thereby protecting the club against dilution of its identity. The Vintage Rockers, unlike most marqueor activity-based motorcycle clubs, do not proselytize.

So what do they do? Unlike the poseur-motorcyclists now adopting the fashionable Harley look, they ride. A lot. For some members—both male and female—as for the original Rockers, their motorcycles are their sole means of transportation. And from> their base in Santa Cruz, they try to gather at least twice monthly for rides through the beautiful coastal mountains, sometimes associating with groups like the Norton Owners Club or the Monterey Bay European Motorcycle Club to join in celebration of Real Steel. And, of course, there is the endless mechanical work to be done on the bikes.

Since the youth of the membership precludes restoration by application of credit cards (so common among older “collectors”), club members, like the Rockers of long ago, do their own wrenching. The results, of course, are bikes continually being worked on. Real Rocker Radford, whose business brings him into contact with many of the Vintage Rockers, notes not only that the club members remind him of himself decades ago, but that their bikes are like his and his mates’ too: “Not perfect,” he says tactfully.

But for riders who grew up in an era of Japanese motorcycles so good that all you need to know to ride or own them is how to pay for them, the trials and rituals of Real Steel are themselves rewarding. A large part of the pride the group feels is based on its members finding, buying, building and rebuilding the bikes to make them fit their own visions of modernbut-classic café racers, whether British, German or Italian. And in seeking out battered old Bonnies and creaking Commandos to learn the lessons of Lucas and Girling and Hermatite, they achieve results among their Japanese-mounted peer group. “They respect us,” notes John, whose Norton reflects the pride and work the young archaeologist obviously put into it, “because they know we have to know what we're doing.”

Do they also respect the VRCC for its studded-and-decorated blackleather style, which so clearly threatens so many people? On this subject Stanger is clear: Group members like their leathers, but they do not necessarily see them as combat gear. Mick Farren, in his book, The Black Leather Jacket (Abbeville Press, New York, 1985), probes deeply into the mystique of the look so well captured by the Vintage Rockers, and emerges with some astute observations about its power. Farren documents all the uses to which the seemingly simple and protective jacket has been put— from clothing combat pilots to juvenile delinquents, from Nazi generals to American policemen, from Rockers to gay-bar habitues—and concludes with these words: “The black leather jacket continues. At times it looks like it will go on forever.”

Among the Vintage Rockers, where the jacket is such an important element, no one doubts it. Yet Stanger and his membership reiterate that what they are about is not a look but a way of club life, in which the look is an element, but only an element.

The other elements may have been distilled most eloquently by a young Rocker interviewed three years before Shannon Stanger was born, whose words are quoted in Stuart's book. Asked to sum up his identity, he said. “I'm a Rocker because I ride a motorbike. To be a Rocker you've got to have a bike and a leather jacket with a studded belt, jeans and hightopped racing boots.”

And then he added. “You’ve got to really love the bike to understand.”

In Santa Cruz, there are at least 25 young people who understand perfectly. So in surf city, as in the East End of London all those years ago, the Rocker beat goes on.

Maybe it'll go on forever. As long as there are Real Steel motorcycles, trustworthy mates and rock n’roll, why should it not? 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

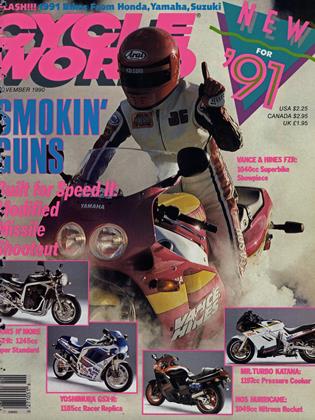

ColumnsUp Front

November 1990 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

November 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

November 1990 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1990 -

Roundup

RoundupA Hotter Zephyr Blows Into the U.S.

November 1990 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupResurrecting Triumph

November 1990 By Alan Cat Heart