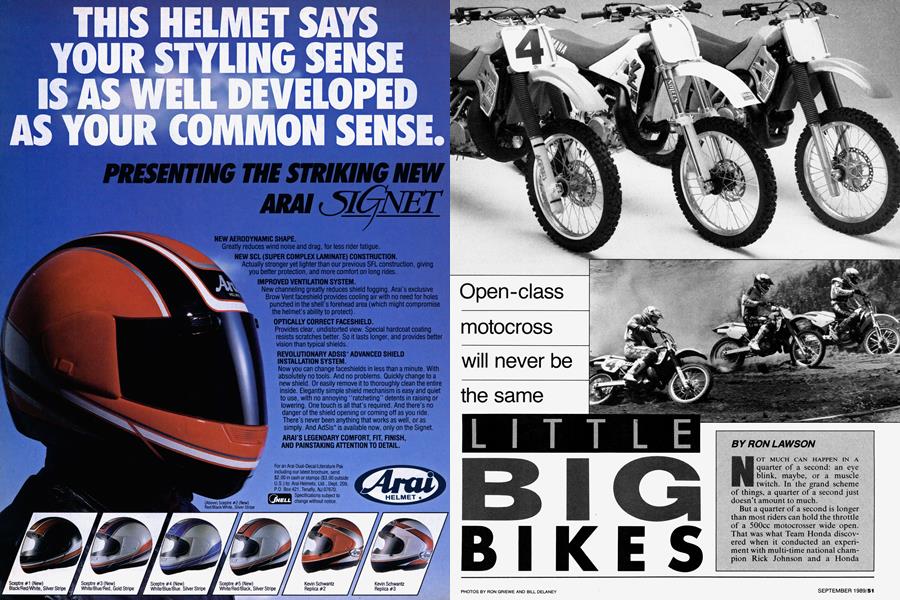

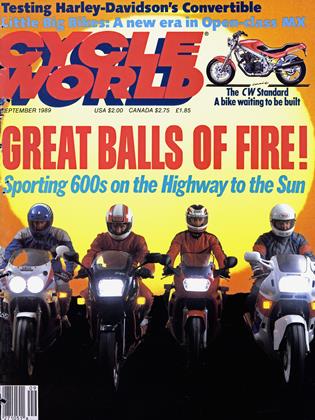

LITTLE BIG BIKES

Open-class motocross will never be the same

RON LAWSON

NOT MUCH CAN HAPPEN IN A quarter of a second: an eye blink, maybe, or a muscle twitch. In the grand scheme of things, a quarter of a second just doesn’t amount to much.

But a quarter of a second is longer than most riders can hold the throttle of a 500cc motocrosser wide open. That was what Team Honda discovered when it conducted an experiment with multi-time national champion Rick Johnson and a Honda CR500R on a typical motocross track. The CR was equipped with computerized testing equipment that recorded how much and how long Johnson was on the gas.

The results showed that even Johnson, one of the greatest riders in the history of the sport, rarely used the 500’s full power potential. Fullthrottle bursts averaged about a quarter-second in duration. A modern 500 simply produces more power than anyone can use.

That’s why a new breed of Openclass motocross bikes has come into being. The Noleen 360 Yamaha and the Klemm Research 285 Kawasaki both are bikes that began life as 250s, then were modified to compete in the Open class. They try to blend the best of both worlds: enough power to get the job done, but not so much as to be unmanageable. And that raises a question: How much horsepower is enough to run against the big bikes?

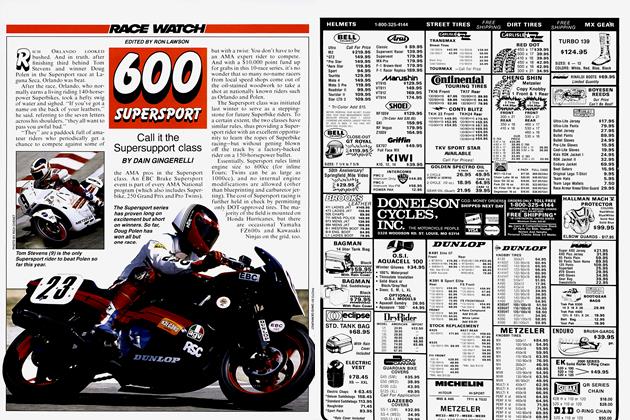

To get the answer, we took both bikes, along with a stock Kawasaki KX500, to motocross instructor Russ Darnell’s private training-camp in the hills near Hemet, California. Darnell’s track was designed to be anything but easy. At the time we visited it, the course was dry and hard: a hilly, one-mile loop-dotted with rocks ranging from golf-ball sized to coral-reef sized—that allowed our riders, Intermediates and Pros, very little rest.

First came a ride on the stock Kawasaki KX500. Currently, the KX

ranks on top of the Open-class hill, producing more power than any other knobby-shod motorcycle sold. But that day in Hemet, all that horsepower really didn’t matter. On Darnell’s long uphill, the KX rider had to strike a careful balance between too>

much and too little throttle—either caused wheelspin on the hardpack surface. Without enough throttle at the bottom of the hill, the bike didn’t have the momentum to make the climb, so the rider compensated with too much gas, too late. The rear

wheel alternately spun and grabbed at brief bits of traction.

A steep downhill, with a sharp turn at the bottom, followed. Making the turn required careful braking. And, because the 500 weighed a good 15 pounds more than its 250-derived

counterparts, braking had to begin earlier. And the big KX’s greater displacement created a greater chance of locking up the rear wheel.

Darnell’s track then treated our riders to a series of off-camber turns and twisty sections, few of which al-

lowed a fully open throttle on the KX500. Even Rick Johnson would have had to think twice about keeping the gas on for an entire quartersecond here. The problem wasn’t having too little room to open up the big Kawasaki—Darnell’s track was

spread-out and wide. The difficult part was avoiding wheelspin and getting traction. Having the throttle open doesn’t do you much good unless you're going someplace as a result. In short, the KX500 was a handful.

Next, the Klemm Kawasaki was unbottled. After riding the 500, the 285 made all our riders feel like heros. Dialing up just the right amount of power to climb the big hill was easy: The 285 was predictable and controllable. And on the downhills, the 250-based bike was much easier to control.

The Klemm bike had a powerband exactly like a KX250—it’s just that there was more power everywhere. The bike had good low-end, and then spun quickly up to its mega-rpm topend. The machine was stronger than any 250 on the market, although it still was outgunned by the KX500 in a straight line. Of course, on most motocross tracks there are no straight lines.

Splitting the difference between the Klemm 285 and the KX500 was the Noleen 360. The powerband of the Noleen bike wasn’t quite like a 250, but then it wasn’t quite like a 500, either. The bike had an extremely smooth delivery off the bottom, and demanded to be shortshifted, because at higher rpms, where the Klemm bike liked to be ridden, the Noleen bike just flattened out and began to vibrate. Nowhere in the rpm range did it ever hit with a sudden rush of power. That allowed> the 360 to hook up and get traction where the KX500 and even the Klemm bike would spin. Of the three, the Noleen bike seemed to be in the mildest state of tune, suggesting that a good tuner could make a real fire-breather out the machine. But of course with more horsepower, the machine’s tractability would suffer.

On that track on that day, either one of the Little Big Bikes would easily walk away from the stock 500. In a race, the 500 might get the holeshot, but the Klemm and the Noleen bike would be dicing for the lead by the second turn.

But Darnell’s track was an extreme that day—highly technical and very slippery. To give the 500 another chance, we took all three machines to the badlands of the Southern California desert, a hilly, sandy playground that requires horsepower as much as agility. But even there, the Klemm and Noleen bikes held the upper hand. For this round, the 285 had a distinct advantage in the shape of Klemm’s flywheel kit: We bolted on the optional 15 ounces of flywheel weight between rides, and that made the Kawasaki much more tractable. Both the 500 and the 360 would have benefited from similar treatment. The Noleen bike, despite having such a smooth powerband, was more difficult to control than the Klemm bike simply because it was easier to stall when applying the rear brake. After all, the 360-kitted Yamaha is a legitimate Open bike with crank weight designed for a 250.

Still, the 500 was harder to control yet. The big KX would stall easiest of all and was the hardest to handle in just about any situation. It’s interesting to note how dramatically horsepower effects handling. The 500 feels bigger, heavier and clumsier than it really is, simply because it has so much power. Sure, there are tracks that suit the KX500 better, that require enough raw horsepower to give a full-sized 500 an advantage. But those are rare. On most courses, the only place a 500 can use its awesome potential is between the start and the first turn. After that, toe much horsepower just gets in the way. That makes these two Little Big Bikes the best bets in the Open class today.

Of course somewhere there might be someone who can hold his 500 open for a full second or two. And if you ever meet him, hopefully not in some dark alley, you might ask him to share his secrets. Rick Johnson, for one, would love to hear from him. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

September 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

September 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

September 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupA New Supertwin?

September 1989 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupItalian Traffic Solution

September 1989 By Alan Cathcart