ADVENTURE IN THE ANDES

RACE WATCH

The Incas Rally: A lifetime squeezed into 10 days

RON LAWSON

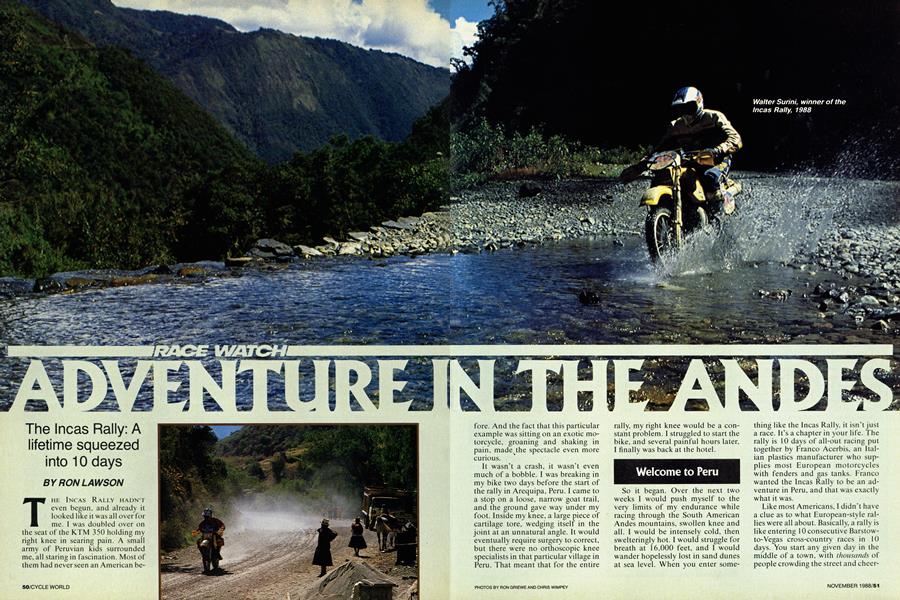

THE INCAS RALLY HADN’T even begun, and already it looked like it was all over for me. I was doubled over on the seat of the KTM 350 holding my right knee in searing pain. A small army of Peruvian kids surrounded me, all staring in fascination. Most of them had never seen an American before. And the fact that this particular example was sitting on an exotic motorcycle, groaning and shaking in pain, made the spectacle even more curious.

It wasn’t a crash, it wasn’t even much of a bobble. I was breaking in my bike two days before the start of the rally in Arequipa, Peru. I came to a stop on a loose, narrow goat trail, and the ground gave way under my foot. Inside my knee, a large piece of cartilage tore, wedging itself in the joint at an unnatural angle. It would eventually require surgery to correct, but there were no orthoscopic knee specialists in that particular village in Peru. That meant that for the entire rally, my right knee would be a constant problem. I struggled to start the bike, and several painful hours later, I finally was back at the hotel.

Welcome to Peru

So it began. Over the next two weeks I would push myself to the very limits of my endurance while racing through the South American Andes mountains, swollen knee and all. I would be intensely cold, then swelteringly hot. I would struggle for breath at 16,000 feet, and I would wander hopelessly lost in sand dunes at sea level. When you enter something like the Incas Rally, it isn't just a race. It's a chapter in your life. The rally is 10 days of all-out racing put together by Franco Acerbis, an Ital ian plastics manufacturer who sup plies most European motorcycles with fenders and gas tanks. Franco wanted the Incas Rally to be an ad venture in Peru, and that was exactly what it was.

Like most Americans, I didn't have a clue as to what European-style ral lies were all about. Basically, a rally is like entering 10 consecutive Barstow to-Vegas cross-country races in 10 days. You start any given day in the middle of a town, with thousands of people crowding the street and cheer-

ing deliriously. And then you ride at a sedate pace to the edge of town where the timed “special test” begins. And from that point on you’re racing on an unmarked course, finding your way with only a road book and an odometer to tell you when to turn and where to go. Somewhere, 60 to 300 miles later, the special test will end near another town. Your time is recorded there, and then you ride at a leisurely pace to the official finish in the center of town where you’ll once again be mobbed by masses of enthusiastic locals. It’s at the end of each day that the Incas Rally differs from most other rallies. In the Paris-to-Dakar, for example, the riders just roll out a sleeping bag and struggle to get some shut-eye before starting it all over again the next day. In the Incas rally, the riders usually stayed in the best hotels in Peru, ate well and were well-prepared for the next day.

This year there was a small handful of Americans who braved the wilds of Peru in the Incas Rally. The most formidable was Scot Harden, of Baja 1000 fame. The most famous was Malcolm Smith, of “On Any Sunday” fame. I was there, with no rally experience, just to test my own endurance, just like New Englander Gary Doski and grizzled, 62-year old Jessie Goldberg. David Dunn and Alan Naille were trail riders who came just to see if they could make it. None of us knew quite what to expect.

What makes rallying so tough? It isn’t the terrain—there’s nothing so hard about fast, rocky fireroads. Rather, a rally is a battle with the rider on one side, and fatigue, illness and distance on the other. The length of a day can be enormous, easily involving over 12 hours of riding for some people. And all during that time a rider not only has to try to ride as fast as he can, but go fast in the right direction, as well.

You left what on?

The first part of your body to give way isn’t your arms, your legs or your back. It’s your mind. After a couple of days in the saddle, you can get pretty stupid. Example: At the end of Day Two, I changed front wheels, and forgot that the pick up for my ICO odometer was on the old wheel. That’s only a little stupid; I got worse. At the start the next day I couldn’t figure out why my odo wouldn’t work and developed a mild state of panic. Without an odo, you get lost. It’s that simple. Gary Doski was start-

ing a few minutes behind me, so I decided to wait and follow him, let him do all the navigation. But once underway, my bike started running so poorly that I couldn’t keep up with Gary, or anyone else, for that matter. The machine would sputter and cough, running for all the world like the choke was on. It wasn’t until 200 kilometers had gone by and the bike had run completely out of gas that I discovered why. The choke, naturally, was on.

So, there I was, out of gas on a frozen mountain in Peru with an I.Q. that was barely in the double digits. My knee hurt, I was cold, and even if I had gas I wasn’t sure I could find my way to the end of the special test without a working odometer. Most of the other riders had long since passed me, and I had nothing but a few llamas for company. Are llamas carnivourous? I wasn’t sure. I gave them a wide berth and started pushing my motorcycle.

That’s when I encountered Buster the Indian. I don’t what his real name was, or why he lived in the middle of this icy wilderness. In fact, I don't know anything about him besides he didn’t have a tooth in his head, he could have been a hundred years old, and he saved my butt. I simply pointed at the fuel tank of the motionless motorcycle, and he spun around and headed back over the hill, obviously excited to be of help and jabbering with much more energy than I could have managed even at my best. I couldn’t keep up, but I watched as he disappeared into a mud hut in the distance. When he came back he was carrying a Coke bottle full of gas. God only knows

what he used it for.

I made it in that day—it was remarkable how much better the bike ran with the choke off. I had told Buster I was going to buy him a new car as soon as I got back to the States. He just grinned and nodded. I sure hope he doesn’t know any English.

Stop that grinning

Malcolm Smith never had any such problems, at least not that I saw. At the end of every day he would be calmly working on his bike, which, for some reason, used less gas, fewer

Just what is a rally bike, anyway?

RALLY BIKES ARE BUILT WITH ONE THING IN MIND, SURVIVAL. WHEN you’re 100 miles away from the next.human being, you don’t want to have bike worries.

But different types of rallies require different types of bikes. Unlike the Paris-to-Dakar, where speed is essential, the Incas Rally consists half of rock piles and half of twisting dirt roads. A mid-size, reliable enduro bike is the perfect machine for that type of terrain. That’s why most of the bikes entered in the Incas Rally were KTM 350s, built especially for that event. Rally promoter Franco Acerbis provided most of the bikes in the rally, and requested numerous changes from stock 350s, including wider gear ratios, different disc rotor material and brake pads, massive sevengallon fuel tanks, rim pins in place of tire bead clamps and speedometers mounted to the right side of the handlebars.

For the most part, the Cycle World entry was identical to other 350s. We did run Michelin Bib Mousse airless tires on about half of the days to avoid flats, and we used an ICO odometer as a back-up to the stock odometer. During the event, we went through a short list of spares, including two silencers, two stock odometers, four sets of rear brake pads, and assorted clamps and carburetor jets.

After it was all over, we couldn’t have asked for a more trouble-free rally, at least mechanically. The bike ran perfectly for over 2500 miles— despite the sometimes terrible gasoline and an improperly mounted air cleaner that passed sand during one of the days, the KTM engine never required a single part.

In fact, the only part that we continually had trouble with throughout the rally, was the part that sat behind the bars. And unfortunately, that was one part we weren’t allowed to change. Ron Griewe

tires and fewer brake pads than anyone else’s. One day, Malcolm came in complaining that he had crashed so hard that he was lucky to be alive, that he barely sputtered to the end of the special test, dizzy from this terrible get-off. But at the end of the day when the times were posted, Malcolm had one of the best times of the day. What a brush with death. I figure that terrible crash of crashes cost him at least 20, maybe 30 seconds.

At first it bothered me that this 47year-old man was doing everything so much better than I was. Then I decided that he was really a robot, put here to humiliate us humans. Robots don’t get tired or sick or hurt their knees. They just grin. Malcolm grinned a lot.

But even Malcolm seemed to be slightly affected by a flu bug of some kind that hit all the Americans halfway through the event. That was all we needed. We were already tired and dehydrated—water is a rare commodity in Peru—when this virus took what little energy reserves we had left. It was on one of the very longest days, one that took us through the Amazon jungle, that it hit me the hardest.

You always hear runners and cyclists talking about “hitting the wall,” when their bodies are so depleted that they simply can’t go any farther. I found out on that fifth day that the wall can be moved. Runners would know that too, if, for example, they were being chased while they ran. If you absolutely have to keep going, then you can. On that fifth day, I kept going all the way to the finish, even though I was dying to stop. Otherwise, I would have been rewarded by darkness, cold and hunger.

Kiss your own baby, Ma'am

And, of course, the finish is something to look forward to. The only part that was harder to survive than a long day of riding was the end of a long day of riding. Obstacle number one: thousands of kids. At the finish, they would crowd against me from all directions, shouting, tugging and pulling, anything to catch my attention. To these kids, the Incas Rally was the only excitment to pass through their village all year. They don’t have video arcades, movies or even TV in most of these areas. So a motorcycle race is the Peruvian equivalent of Martians landing on the White House lawn.

At first, it was a blast. “Autograph? Sure, anything for my fans. Here, have a sticker.” But even Ozzie and Harriet couldn’t maintain a benevolent, child-loving attitude by the fifth or sixth day of such chaos. I would be

tired, dizzy and hot, and between me and a hot shower would be this throng of humanity, waving pencils and wanting me to sign pieces of

trash they had picked off the street. You could blow your nose on their autograph books and they would still love you and treasure the souvenir forever.

Once through the mob of kids, I still had to get through the local press. I figure this is a perverse justice for all the rude questions I've asked racers hot off the track at Daytona or Laguna. I would barely be capable of understanding English and they would shout questions at me in Italian and Spanish. And even if I understood the question, I sure wouldn’t understand my own answer. I'd just stand there and mumble into the microphone until they got tired of me and turned their attention to another rider, stumbling out of the crowd. Malcolm, of course, always signed the autographs and answered the questions with all the patience in the world, grinning the whole time. Robots can do stuff like that.

By far, the most impressive reception we recieved was in Andahuaylas (And-why-lus), a town isolated in the mountains at about 12,000 feet. When we arrived, the street was crowded with the entire population of the town. A band played and the mayor watched from his balcony while each rider was given a bouquet

of flowers. Then a small Indian child was held up for each rider to kiss while the crowd cheered wildly. It was like a scene from a hot-fudgeand-apple-pie dream. Any second, I

expected the little girl to turn into a dragon that would gobble up the entire band and belch fire in the mayor’s face. But that didn’t happen. It wasn’t a dream at all.

Franco Acerbis eventually led us to sanctuary in a small café. The locals weren't allowed in, so they simply pushed their faces and bodies against the plate-glass window until it became a pressed-human wall. It was a little scary.

Won't This Rust Your Machine Gun?

What followed was one of the weirdest nights of my life. Andahuaylas isn't known for its hotels. In fact, it doesn’t have any. What it does have is a military academy, complete with a bunkhouse. Now, if you know how stark your average military academy is in the USA, one of the richest nations on earth, you can try to imagine what one would be like in Peru, one of the poorest nations on earth. Imagine a block building with no glass in the windows and no doors in the doorways. It did have running water, though, and a long shower would have been all the luxury I needed.

I peeled off my riding gear, and one of the guards—they were never out of sight—escorted me to the shower room just as the sun was going down. At that altitude, the temperature drops like a stone when it gets dark. I was shivering in the suddenly sub-freezing air when the guard pointed at the nearest showerhead and smiled slightly. Below it was a single knob. No choice of hot or cold, just off or on. I closed my eyes, turned the knob and braced for impact . . . and nothing happened. The guard laughed openly, walked over to the master control, and flipped it wide open. Nothing could have prepared me for the blast that followed. What came out of that showerhead had no right to be liquid. The air in that room already was in the 20s, and the water seemed far colder. In fact, the word “cold” doesn’t even apply. My nerve endings could only tell that the temperature was extreme. It could have been scalding hot and provided the same sensation.

It was, needless to say, a brief shower. The guard remained, machine gun over his shoulder, smiling the whole time. They must have had orders never to leave us alone, even if it meant getting wet. All that night, the guards watched over us as we tried to sleep in the undersized bunks. The lights remained on, and the icy wind howled through the open building all night. It was a relief to get up at 4:30 am and chip the ice off the KTM’s seat. Andahuaylas had been friendly, but I was happy to leave.

Which way to the ocean?

The week continued, and life became easier. While I still couldn’t extend my leg, it was no longer painful. All traces of the mysterious Peruvian flu bug gradually disappeared, and as we descended from the mountains, the KTM began running stronger than ever.

On the eighth day, the rally took us on a short loop around the coastal city of lea. It was an easy ride, and I felt better than I had in days. I actually topped the 500 class on that stage of the rally, finishing fourth overall with only three 600s in front of me.

Of course, that was the good news. The bad news was that each day, your starting position was determined according to how you finished on the previous day. So, on the ninth day, a day that would take us through disorienting sand dunes where getting lost would be easier than ever, I would start near the front of the pack.

The ride started in heavy fog. Somewhere in the mist I passed Roberto Belmonte, the local hero on a Honda 600. That left me with only two tracks to follow. It was only a few kilometers before I was hopelessly lost. And right on cue, the bike stopped running so well. Actually, I thought it was going to stop running altogether. I soon found myself in the same limited-I.Q. mode of semipanic that had almost taken me out of the rally on Day Three. The fog kept beading up on my goggles, making it even harder to figure out where I was. There were no roads, no tracks, no landmarks. Just sand.

But I knew that the course would eventually go along the beach, so all I had to do was find the water, and go there. Simple enough. By the time I did find the water, though, I discovered another problem. There was no beach—just a cliff dropping off into the surf. And there was no path paralleling the ocean. And the bike was running worse. And I was almost out of gas. Again.

It wasn’t looking good. Lost, out of gas and on a bike that sounded like it was going to grenade any second. I had come so far, and now everything I’d worked for was coming apart at the seams. About the only miracle that could save me was the rally being called to a halt right then and there.

God smiled. The rally was called to a halt, right then and there.

I came to a small fishing village where virtually everyone in the rally was waiting, as well as Franco Acerbis himself. It seems that the tide had come in and the rally had to be postponed for a while before the course would again become passable. Then everyone would be allowed to continue in the order in which they had arrived. Not only had I found the course, but I had several hours to work on the bike and scrounge gas from the other riders.

Malcolm spotted my problem before I did; the silencer core in my bike’s pipe was busted. Making the machine run right was simply a matter of gutting the silencer and putting up with the noise for the rest of the day. I let Malcolm do most of the work on my bike. Again, I finished.

Odd. Malcolm had so few problems of his own that he had to take responsibility for other people’s hardships. When the entire affair ended the following day, I had the distinct feeling that he and I had ridden entirely different events. I had had two or three major catastrophies every day. He had had a sunny vacation in southern Peru. I struggled through the most demanding physical test of my life. He rode the event only because it was the best way to see the countryside. I was unbelievably proud of my ninth-place overall finish. He was indifferent to his fourth-place finish. Clearly, not the same event.

Doski would have done anything to finish right beside Malcolm. Like me, he became fascinated by Malcolm’s perfomance throughout the rally. But unlike me, he became obsessed with trying to keep up with the incredible 47-year-old. Eventually, Doski pounded his bike and his body into junk, and what started off as great top-ten ride ended up a struggle to finish in 30th. The top American was Harden, as expected, who finished third behind Italian ISDE riders Walter Surini and Alessandro Gritti. Goldberg, Dunn and Naille didn’t finish.

And that’s a shame. Because even if it’s just another entry on Malcolm Smith’s long list of achievements, finishing the Incas Rally is something I’ll think about and be proud of for the rest of my life. I don’t think I have ever tried so hard or been so miserable as I had been in that rally.

But I know that I had never had as good a time.

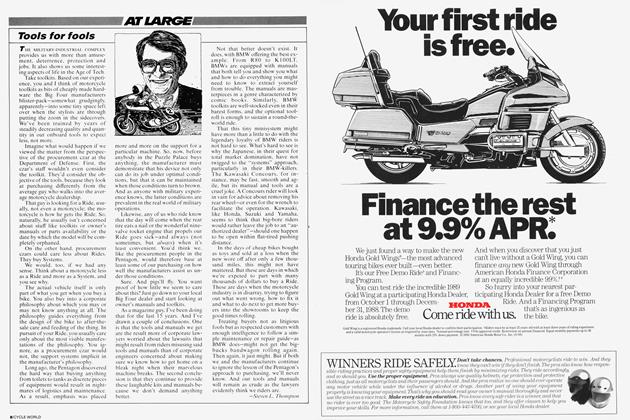

Survival at Suzuka

To win a GP you have to go fast. To win an endurance race, you have to endure. But to win the Suzuka 8Hour, you have to endure going fast for a very long time. Make no mistake, the 8-Hour race held at Suzuka in Japan is the fastest, most competitive endurance race there is. It’s also the only endurance race in the world that consistently attracts most of the top GP riders. And this year, the eleventh running of the event, was no different. Wayne Gardner and Niall Mackenzie were there on an HRC Honda RVF750; Kevin Schwantz and Doug Polen shared a Suzuki GSX-R750-based endurance machine; and Wayne Rainey rode with last year’s co-winner, Kevin Magee, on a Yamaha YSF750.

After eight hours of racing,

Rainey and Magee were in front, marking the first time an American has been a co-winner since 1984 when Mike Baldwin and Fred Merkel scored the win. Overall, though, more Americans have won at Suzuka than riders from any other single country. Including, incidentally, Japan.

The Bubba Pro Series

7"he Camel Pro series is just past the halfway mark, and already there’s little doubt about who the next champion will be. “Bubba’s going to win the championship. That’s a guarantee,” says the man who currently is running third in the championship race, Steve Morehead, about Camel Pro series points leader Bubba Shobert.

Shobert is the only rider to earn points in every single one of the events so far. In fact, he’s finished in the top three in every event except one, where he got ninth. If Shobert holds on to his incredible point lead for the remaining six races, he'll tie Carroll Resweber’s record of four consecutive Grand National championships. And with 38 career wins under his belt, he also stands a good chance of eclipsing Jay Springsteen’s all-time win record, which currently stands at 40. Morehead’s hope: “Maybe we can force Bubba to wait until Springfield (September 4th) to clinch the title.”

Who’s Out There, Anyway?

IVhen Pepsi decided to sponsor motorcycle roadracing last year, it had good reason: According to that company’s research, over one million spectators went to motorcycle Grands Prix last year. That’s even more than the total for Formula One auto racing. The 1 5 races last year averaged 87,000 per event, the highest attendance coming at Czechoslovakia where 200,000 fans showed, and the lowest being Brazil with 40,000. This year, the average is expected to reach over 90,000.

It's a fair assumption that Pepsi and the tobacco companies aren’t the only ones to take note of motorcycle racing’s publicity potential. If these kind of numbers continue, you can bet that other sponsors of this caliber will follow.

Pick A Class

A sk Eric Geboers what size bike he currently rides and it might take him a while to remember. He just became the first rider in history to collect world motocross championships in all three GP classes by taking the 1988 500 title. What made it even sweeter was that he did it in his home country, on the Namur course in Belgium, with a fifth place in the opening moto.

Geboers won his first world championship in the 125 class in 1982, riding for Suzuki. He repeated in 1983, then claimed the 250 class for Honda in 1987. This year he moved up to the 500s, and with Britain's David Thorpe having a terrible sea son due to repeated injuries. Geboers took the title quite easily on his Honda. In the final point standings. American Billy Liles was eighth.

Crash for Cash

The Mid-Ohio round of the U.S. Superbike Championship turned the entire series-and a few riders-up side down. Suzuki's Doug Polen en tered the race with a slight points lead over Honda's Bubba Shobert, and that lead looked even more se cure when Shobert crashed hard in practice, totally destroying his Honda.

But Shobert's team came back, rebuilding the bike almost from scratch before the race. And in the race, it was Polen who crashed, giv ing up the win to Shobert on the last lap.

But as Yogi Berra said, it's not over `til it's over. The second-place finisher at Mid-Ohio, Scott Gray, protested Shobert's rebuilt machine, claiming the frame was illegally re placed. The protest was denied, but now that decision has been ap pealed. Whichever way the final ver dict goes will probably decide who will become the next Superbike champion of the United States.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialHumble Beginnings

NOVEMBER 1988 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeTools For Fools

NOVEMBER 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Importance of Being Earnest

NOVEMBER 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

NOVEMBER 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupElections 1988

NOVEMBER 1988 -

Letter From Japan

NOVEMBER 1988 By Koichi Hirose