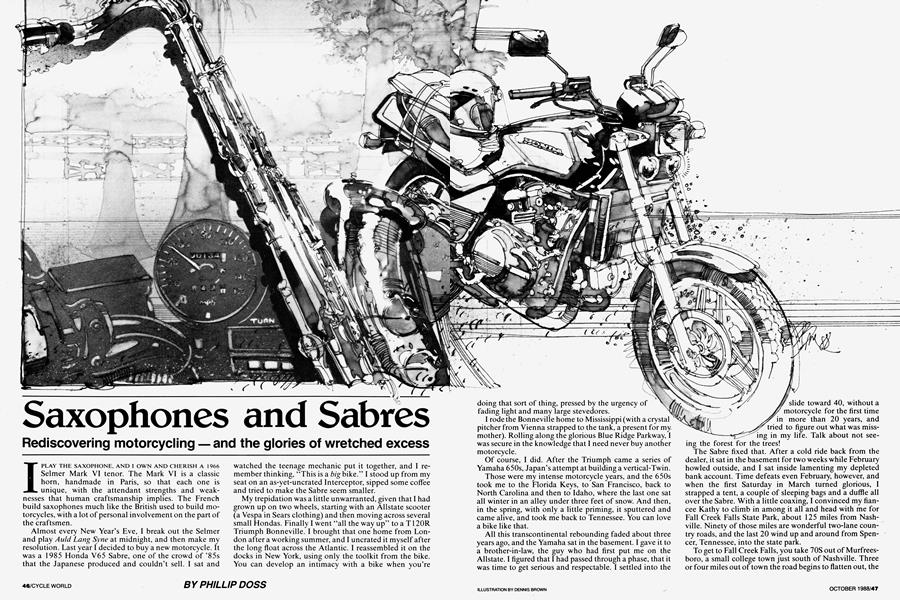

Saxophones and Sabres

Rediscovering motorcycling — and the glories of wretched excess

I PLAY THE SAXOPHONE, AND I OWN AND CHERISH A 1966 Selmer Mark VI tenor. The Mark VI is a classic horn, handmade in Paris, so that each one is unique, with the attendant strengths and weaknesses that human craftsmanship implies. The French build saxophones much like the British used to build motorcycles, with a lot of personal involvement on the part of the craftsmen.

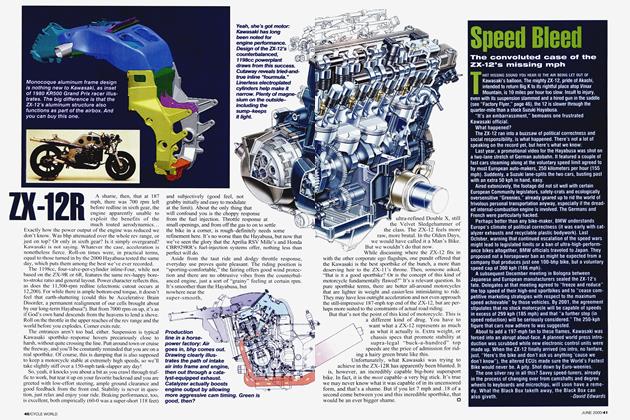

Almost every New Year’s Eve, I break out the Selmer and play Auld Lang Syne at midnight, and then make my resolution. Last year I decided to buy a new motorcycle. It was a 1985 Honda V65 Sabre, one of the crowd of ’85s that the Japanese produced and couldn’t sell. I sat and

watched the teenage mechanic put it together, and I remember thinking, “This is a big bike.” I stood up from my seat on an as-yet-uncrated Interceptor, sipped some coffee and tried to make the Sabre seem smaller.

My trepidation was a little unwarranted, given that I had grown up on two wheels, starting with an Allstate scooter (a Vespa in Sears clothing) and then moving across several small Hondas. Finally I went “all the way up” to a T120R Triumph Bonneville. I brought that one home from London after a working summer, and I uncrated it myself after the long float across the Atlantic. I reassembled it on the docks in New York, using only the toolkit from the bike. You can develop an intimacy with a bike when you’re doing that sort of thing, pressed by the urgency of fading light and many large stevedores.

PHILLIP DOSS

I rode the Bonneville home to Mississippi (with a crystal pitcher from Vienna strapped to the tank, a present for my mother). Rolling along the glorious Blue Ridge Parkway, I was secure in the knowledge that I need never buy another motorcycle.

Of course, I did. After the Triumph came a series of Yamaha 650s, Japan’s attempt at building a vertical-Twin.

Those were my intense motorcycle years, and the 650s took me to the Florida Keys, to San Francisco, back to North Carolina and then to Idaho, where the last one sat all winter in an alley under three feet of snow. And then, in the spring, with only a little priming, it sputtered and came alive, and took me back to Tennessee. You can love a bike like that.

All this transcontinental rebounding faded about three years ago, and the Yamaha sat in the basement. I gave it to a brother-in-law, the guy who had first put me on the Allstate. I figured that I had passed through a phase, that it was time to get serious and respectable. I settled into the slide toward 40, without a motorcycle for the first time in more than 20 years, and tried to figure out what was missing in my life. Talk about not seeing the forest for the trees!

The Sabre fixed that. After a cold ride back from the dealer, it sat in the basement for two weeks while February howled outside, and I sat inside lamenting my depleted bank account. Time defeats even February, however, and when the first Saturday in March turned glorious, I strapped a tent, a couple of sleeping bags and a duffle all over the Sabre. With a little coaxing, I convinced my fiancee Kathy to climb in among it all and head with me for Fall Creek Falls State Park, about 125 miles from Nashville. Ninety of those miles are wonderful two-lane country roads, and the last 20 wind up and around from Spencer, Tennessee, into the state park.

To get to Fall Creek Falls, you take 70S out of Murfreesboro, a small college town just south of Nashville. Three or four miles out of town the road begins to flatten out, the

wWhen we came bach, stuck on my speedometer was an invitation to visit South Carolina. I was beginning to feel like part of the family again?*

bread-and-beer markets become less frequent, and it’s easy to sit back and feel the land. It begins to rise almost imperceptibly, and then through Woodbury and McMinnville you come to big, sweeping curves that beg for a little more speed and a little more lean. Highway 30 just out of McMinnville begins to get serious. The climb becomes steeper and the curves turn back on themselves. And it was here where I began to appreciate what had happened to motorcycles while I had been in my vertical-Twin coma.

My first surpise was that the Sabre handled. Over 500 pounds of bike, with another 325 pounds of folks and gear, and still it nosed into uphill curves with hardly any effort on my part. Ld always been told that when I gave up my Triumph I’d give up that feel of response, that quickness through corners, and I d believed that, because I felt a little of it slip away when I went from the Bonneville to the Yamaha. This is not to say that the Sabre handles in the same league with the Triumph, or at least with my memories of the Triumph, but 1 certainly didn’t have to wrestle the thing, and there was none of the big-bike wallowing I’d expected.

Then came the best surprise: the power of the thing. It pulled all that load up and out of the curves and through the next climb with no effort. And the tachometer face itself was a revelation: redlined at 10,000 rpm. I shudder to remember what my 650s felt like at even half that engine speed. At anything past 5000 rpm, they always seemed on the brink of something ominous, the pistons yowling and protesting and threatening to abolish themselves at any instant. But the Sabre at 5000 rpm just purred, like it was doing what it was built to do.

The ride into Fall Creek Falls State Park is truly relaxing. The road is divided by a wide median, so that most of the time the other lane is not even visible. For our visit, the trees were still bare, except for the occasional cedar or pine. And here and there, the mountain laurel stood out green against the lower half of the big hardwoods. We had our pick of campsites. The wood had already been cut and stacked by the clearing crews (1 can’t say enough about Tennessee State Parks), so we popped up the tent, showered and made for the lodge and dinner overlooking the lake.

After dinner we hiked down to the bottom of the falls and stood in the mist. When we came back, stuck on my speedometer was a card from the Southeastern Honda Sport Touring Association, with an invitation to visit South Carolina. I was beginning to feel like part of the family again. Latei that night, we sat and poked the fire, while the couple down the way entertained the campground with some soft harmony singing.

Of course we slept like babies—the long day and mountain air made sure of that—but at 7:30 Sunday morning we woke up to the pat-pat of some pretty fat raindrops on the tent fly. We scurried around and got things packed, had a quick breakfast and headed home. Our 70-and-sunny had turned into 50-and-rainy, and I discovered that some things about motorcycling hadn’t changed; that is, when it rains, you either have a good rainsuit and stay dry, or you

don’t and you get wet. In five minutes we were soaked to the skin and shivering.

I’m normally careful about the speed limit, but this time I nudged 70 most of the way home. Again, the Sabre was a pleasant surprise. No difference between 55 and 70 mph, except that we got home sooner.

I had time to think while we were humming along the interstate. I’d often been amused at the hypercritical tests that motorcycle magazines put bikes through. A little disappointed that the new Hurricane will only do 156 mph, are you? That seemed silly at first, but then I realized that the engineers and the manufacturers will always be squeezing a little more out of this idea we have called motorcycling. The difference between 156 and 160 might not be significant on the face of things, but obviously, the knowledge gained from coaxing those extra few mph out of a machine goes a long way toward building a bike that will do the things my Sabre will do. I began to understand that this technological explosion the world is going through is not merely theoretical laboratory stuff, but is practical and directly affects our everyday lives. Real benefits can come from technological excess.

I’d had a pretty good relationship with my Triumph that had started in earnest on the docks of New York. Through the years, I’d come to accept maintenance as part of the motorcycle mystique, just as I’d accepted the notion of hands made numb by engine vibration. I tuned the Triumph so often that it became second nature, something I could do in the parking lot after a long lunch to let the valves cool. But I don’t want to tune the Sabre, and except for oil changes and the occasional valve adjustment, I don’t have to.

That, as I see it, is a real benefit. And if it comes from technological excess, then bravo for excess and let’s have more of it.

My hands were blue and wrinkled from the cold and the wet when we pulled into Nashville. The gear was soaked, and while we unloaded it, the bike sat like a wet and friendly dog in the yard. After a hot bath and a bottle of champagne, I began to appreciate the weekend, even the cold, wet part. I think Kathy felt the same way. I had the card from the South Carolinian, and I had seen Fall Creek Falls. My motorcycle hiatus is over, and I’m pretty excited about that. I might not range as far and wide as I did on the 650s, but I will range, you can count on that.

One more thing. After the champagne took effect, I pulled my Mark VI out of the case and played for awhile. It’s a good horn, no doubt. A classic. But I keep thinking about the difference between the Sabre and the Triumph, and I think that maybe I should stop by a music store and look at some saxophones, just to see if anything has happened since 1966.

Phillip Doss is the chief of research at the Tennessee comptroller's off ce. When he's not riding his Sabre or playing saxophone at Nashville nightclubs, he's working on a novel, he says, ‘just like everybody else in the world. "

View Full Issue

View Full Issue