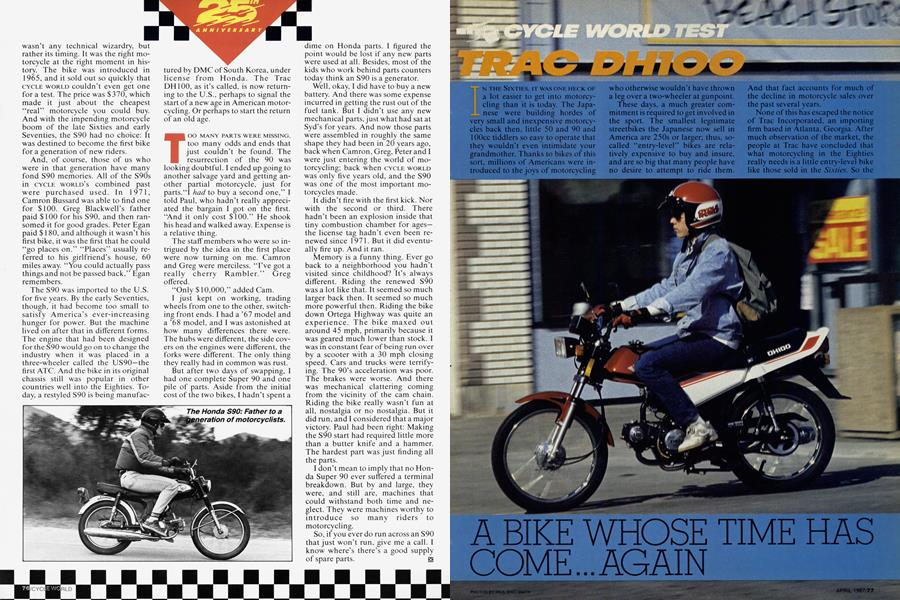

TRAC DH100

CYCLE WORLD TEST

A BIKK WHOSE TIME HAS COME...AGAIN

IN THE SIXTIES, IT WAS ONE; HECK OF a lot easier to get into motorcycling than it is today. The Japanese were building hordes of very small and inexpensive motorcycles back then, little 50 and 90 and 100cc tiddlers so easy to operate that they wouldn't even intimidate your grandmother. Thanks to bikes of this sort, millions of Americans were introduced to the joys of motorcycling who otherwise wouldn't have thrown a leg over a two-wheeler at gunpoint.

These days, a much greater commitment is required to get involved in the sport. The smallest legitimate streetbikes the Japanese now sell in America are 250s or larger; thus, socalled “entry-level” bikes are relatively expensive to buy and insure, and are so big that many people have no desire to attempt to ride them. And that fact accounts for much of the decline in motorcycle sales over the past several years.

None of this has escaped the notice of Trac Incorporated, an importing firm based in Atlanta, Georgia. After much observation of the market, the people at Trac have concluded that what motorcycling in the Eighties really needs is a little entry-level bike like those sold in the Sixties. So the company is importing the DH100, a 97cc, street-legal motorcycle made in South Korea by the Daelim Motor Corporation (DMC).

Actually, the DH100 isn’t like a bike from the Sixties; it is a bike from the Sixties. This single-cylinder, fourstroke tiddler is nothing more than an overbored and restyled Honda S90, circa late 1960s. DMC doesn’t build any bikes of its own design, but instead manufactures a line of smalldisplacement machines mostly for the Korean domestic market, each of them built under license from the Japanese company that originally designed it. The DH100 is one of DMC’s biggest sellers in Korea; and if Trac International has its way, the DH100 will become a top-seller in this country, as well.

At $895, the DH100 costs a full $600 less than Honda’s 250 Rebel, the low-price champion of full-sized motorcycles for the last year or so. In addition, the DH is about $300 cheaper per year to insure than the Rebel. Those two factors alone ought to make the DH100 irresistible to first-time buyers.

Functionally, the DH is an almost perfect beginner’s bike, if for no other reason than it eliminates any element of intimidation. Its nonthreatening, nine-horsepower engine is virtually the same reliable, fourspeed, sohc Single that powered hundreds of thousands of Honda 90s in the late Sixties and early Seventies. About the only difference is the DH’s slightly larger displacement, up from 89cc to 97cc. The engine still has no electric starter, but it easily fires up on one or two light kicks when it’s cold, and on one kick once it’s warm.

Once running, the engine revs rather slowly and has a wide powerband, characteristics that make the DH easy to ride and keep under control. First gear is rather tall, so the clutch must be engaged slowly while keeping the engine spinning at fairly high rpm. Although the DH can stay ahead of automobile traffic from stoplight to stoplight, it can’t accelerate quickly enough to get novices into trouble; and since it tops out at around 58 mph, the DH100 isn’t likely to frighten anyone with sheer speed, either.

Nor will it win any awards for having the plushest ride—one of the prices to be paid for having minimalcost suspension. The low-tech front fork cushions smaller bumps without much difficulty, but sharper, bigger bumps give the rider a distinct jolt. The twin rear shocks also are timetravelers from the Sixties that allow only two inches of wheel travel; and like the fork, they lack the springing and damping sophistication required to handle any real bumps.

Partly due to its stiff suspension, but mostly because of its very light weight and short wheelbase, the DH handles and responds with exceptional quickness. It feels taut and unusually light, and flicks from side to side with ease, making cornering an effortless proposition.

Not only that, the DH100 is surprising roomy for such a small bike. The seat is long, thick and nicely padded, and the distance between it and the non-folding footpegs ifr longer than on many larger bikes. In addition, the handlebar props most riders into a comfortable position and gives them plenty of room to move around without straining to reach the grips.

About the only area in which the DH 100 comes up noticeably short is in its brakes. The small, drum front brake is too weak ever to come close to locking the wheel, so it doesn’t offer enough stopping power for most panic-stopping situations. The rear drum works fine in controlled stops, but, like any rear brake, it locks up too easily to be of much use in really hard stops. The DH 100 simply needs a better front brake that employs modern technology rather than one that was a marginal, minimal-cost design even back in the 1960s.

Still, all in all, the DH100 is a charming, capable little bike that could be just what the motorcycle doctor ordered. Some hard-core enthusiasts will no doubt consider the DH cute but insignificant, while others are sure to dismiss it as simply a dumb little toy. But the DH100 is neither. In fact, it well could be the most important motorcycle on the market right now. It has more potential for getting huge numbers of new people aboard two wheels than any other bike currently for sale in the U.S.; and if it succeeds at that, you can bet your eyes that lots of similar bikes will follow.

Hey, it happened before; it can happen again. And if it does, there will be a certain irony in the fact that, in essence, the same bike that played a major role in motorcycling’s first big growth period will have led the way to the second. E3

TRAC DH100

$895

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialThe Best of Rides, the Worst of Bikes

April 1987 By Paul Dean -

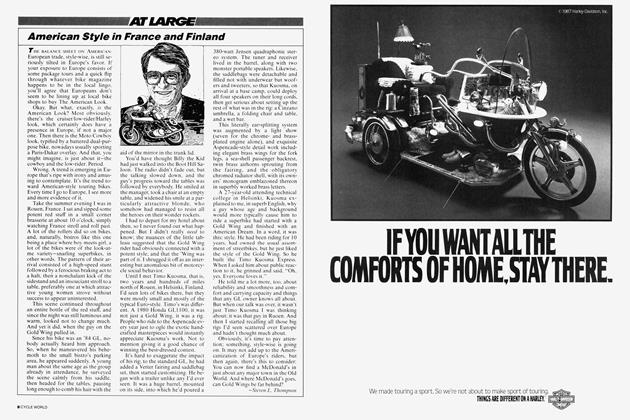

At Large

At LargeAmerican Style In France And Finland

April 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupLending History A Helping Hand

April 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

April 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

April 1987 By Alan Cathcart