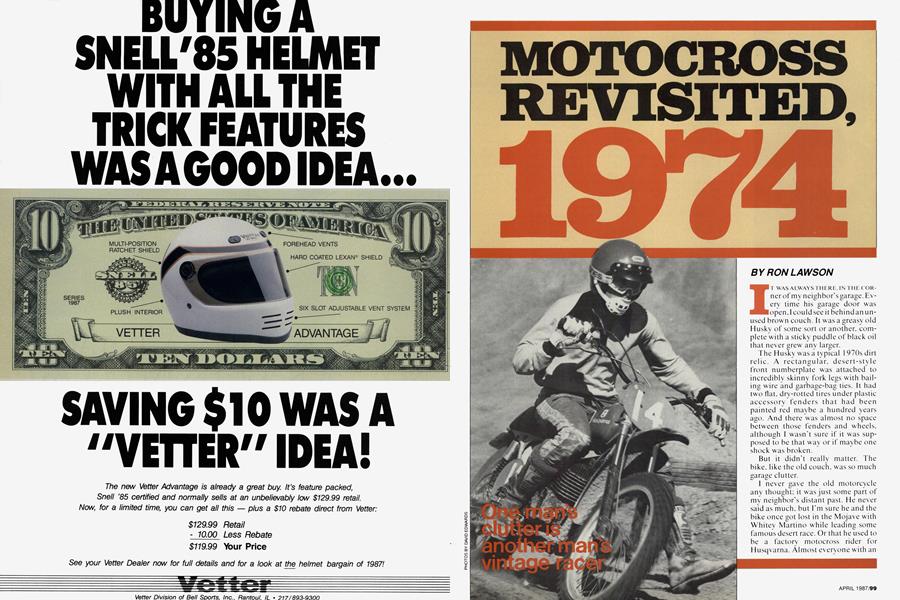

MOTORCROSS REVISITED, 1974

One man's clutter is another man's vintage racer

RON LAWSON

IT WAS ALWAYS THERE. IN THE CORner of my neighbor's garage. Ev ery time his garage door was open. I could see it behind an unused brown couch. It was a greasy old Husky of some sort or another, complete with a sticky puddle of black oil that never grew any larger.

The Husky was a typical 1970s dirt relic. A rectangular, desert-style front numberplate was attached to incredibly skinny fork legs with bailing wire and garbage-bag ties. It had two flat, dry-rotted tires under plastic accessory fenders that had been painted red maybe a hundred years ago. And there was almost no space between those fenders and wheels, although I wasn't sure if it was supposed to be that way or if maybe one shock was broken.

But it didn't really matter. The bike, like the old couch, was so much garage clutter.

1 never gave the old motorcycle any thought; it was just some part of my neighbor's distant past. He never said as much, but I'm sure he and the bike once got lost in the Mojave with Whitey Martino while leading some famous desert race. Or that he used to be a factory motocross rider for Husqvarna. Almost everyone with an old Husky in his garage was, you know.

Basically, the only way to avoid having to hear such tales is not to ask. So I never asked. But one day I got trapped. 1 was working in my garage, and my neighbor came walking up with that purposeful, “Let's be friendly" look in his eyes. I stared down at a nearby valve stem, pretending I was checking the tire pressure.

“Whatcha doin' ?" he asked.

“Just getting ready for the races," I replied, letting a little air out of the tire.

“I got an air gauge you can use. if it'll make that any easier." he offered.

1 looked up. searching desperately for some way to change the subject, and noticed that both the couch and the Husky were sitting out in the street. “What are you doing with those?" I asked.

“That's w hy I came over. 1 wanted to see if you would help me lift them into the dumpster. See. I'm moving and I gotta clean out the garage."

I thought about it a second. “I could use the couch."

“You’ve got them both." And with that, he turned and started back to his garage.

“But I don't want the bike." I said.

“Then you can throw it away."

A year later. I found myself sitting on the start line at Dick Mann's Vintage Dirt Bike Rally aboard a nearpristine Husqvarna 250—yes, that Husqvarna 250. The bike turned out not to be as old as it had looked in the corner of that garage; it was a 1974 250CR Mag. In its day, it marked Europe’s retaliation against the new generation of Japanese motocross bikes. The Japanese had launched a full-scale invasion on the sport, knocking the Europeans off-balance and sending them back to regroup. This Husqvarna was the product of a Swedish counteroffensive. It was a tiny slice of MX history.

Ánd while my Husky didn't look like a museum piece, it didn't look half-bad. either. Once several pounds of grease had been carved off, and new fenders, seals and bearings had been installed, the Husky started a new life.

Which points out something very entertaining about new garage clutter. as opposed to old garage clutter. If the Husky had been sitting in my garage since 1974. getting up the enthusiasm to restore it would have been almost impossible. I would have been tired of the same old rust spots and broken parts. But this bike was entirely new to me; every stripped bolt was a revelation, every leaky seal an adventure. I worked on it every night, painting this, welding that, and trying to find a new one of these. It took a couple of months before all the painting, w elding and finding was done—before the bike officially had been restored into . . . well, into nicelooking garage clutter.

In fact, it almost looked good enough to ride.

Now. in 1974. I had already been racing motocross for about a year, so I figured I knew what to expect. Mv '74 Husky would be sort of fast, it would turn sort of well because it is so low to the ground, and the suspension would be sort of terrible.

Wrong. It was amazingly slow, it took an amazing amount of effort to bend the thing around turns, and the suspension was amazingly terrible. The gearing was so tall that pulling third gear was a challenge, made more difficult by the fact that I had to shift twice before I could get into third.

Actually, shifting in general was a chancy proposition. 1 had to pull in the clutch, let the engine rev dow n to an idle, lif't my foot all the way off the footpeg and keep my toes crossed. Sometimes I made it, sometimes I didn’t. But that’s the way Huskys shifted back then.

Not only that, the engine was pipey, although it never quite managed to come on the pipe. And the handlebar was so wide that when 1 got the bike cranked all the way over in a turn. I couldn't reach the outside grip. Motocross sure was a different sport in 1974.

So there I was on the start line of the 250 class at the Dick Mann motocross, on this relic of a motorcycle that was terrible in every way. My only consolation was the thought that everything in the race probably was equally terrible in every way. There was a mean-looking character on another Husky that looked like it had been raced every single week since it was new. And there was this chubby rider on a CZ that was composed mostly of duct tape. He was comparing notes with another CZ owner—at least I think it was a CZ; it might have been just a massive grease collection on wheels. And then there was a guy on a nearly perfect YZ250 twin-shocker, dressed in modern-day white riding gear. But he was an exception; most of the rest of the field looked like they either had bought their gear from the nearest flea market, or stolen it off a neighborhood sidewalk the day after every garage in America had been de-cluttered by government mandate.

But this was a race, even though it didn't look or feel like one. I wasn’t very optimistic, though, because no matter how grim the competition looked, it was a strain to imagine my old Husky actually beating any other motorcycle.

Surprise Number One: I pulled the holeshot. I think it was because I made a big gamble between the gate and the first turn: I shifted into second. Most of the other riders just left their bikes in first all the way up the hill, and I could hear a few unfortunate souls making unsuccessful attempts to shift. Two or three machines might not have even made it.

Disappointment Number One: I was immediately passed, and it wasn't by any super-trick or modified bike. It was the Husky just like mine.

D isappointment Number Two: The chubby guy on the duct-tape special swapped past me on a straight and took over second. That didn’t last long, though; on the next straight his pipe came untaped and cartwheeled across the track, barely missing me. I was back in second. And as the race progressed. I saw more and more parts laying on the track. A fender here, a seat there, a chain and a puddle of oil over there. But my Husky hung in there, keeping all of its parts all the way to the finish.

My confidence was growing. The bike seemed like it had something to prove. When the gate dropped the second time around. I pulled yet another holeshot. Only this time, the guy on the other Husky didn't pass me—mostly because he was back in the pits trying to make his bike run. What’s more, the guy on the CZ was forced to back off. Every time he opened the throttle more than halfway, some part or another would shake off the bike, and even two or three rolls of duct tape couldn’t keep him at a competitive pace.

And so, much to my surprise and delight, the Husky and I won.

What that race taught me, aside from the fact that my Husky was a better machine than I had thought, was that classic-bike motocross racing has an entirely different set of goals than regular MX. In any other kind of motocross, the contest is to see who can make X number of laps the fastest. With classic bikes, the goal is to see who can make X number of laps. In fact, much of the contest is in just making it to the start line in the first place.

The rewards are different, too. Although I had won the second moto and the overall, I didn’t feel like I had done the hard part; rather, the Husky had. At the Dick Mann rally, the riders were only of marginal importance, and the bikes were the stars of the show. At the end of the race, I was more proud of my old piece of garage clutter than any motorcycle I had ever raced.

I'm still proud of it now—although, I admit, I haven’t cleaned it up since the race. One fork seal started drooling right after I put the bike back in the garage (in the corner). Shortly afterward, the resulting puddle stopped growing larger. The problem is that the bike is rapidly becoming old garage clutter. I already know which bolts are stripped and which seals leak; the adventure is gone. But I still intend to restore it to its race-winning former self, probably right before the next Dick Mann rally.

But first I need to make more room in my garage by getting rid of this old brown couch. E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialThe Best of Rides, the Worst of Bikes

April 1987 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeAmerican Style In France And Finland

April 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupLending History A Helping Hand

April 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

April 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

April 1987 By Alan Cathcart