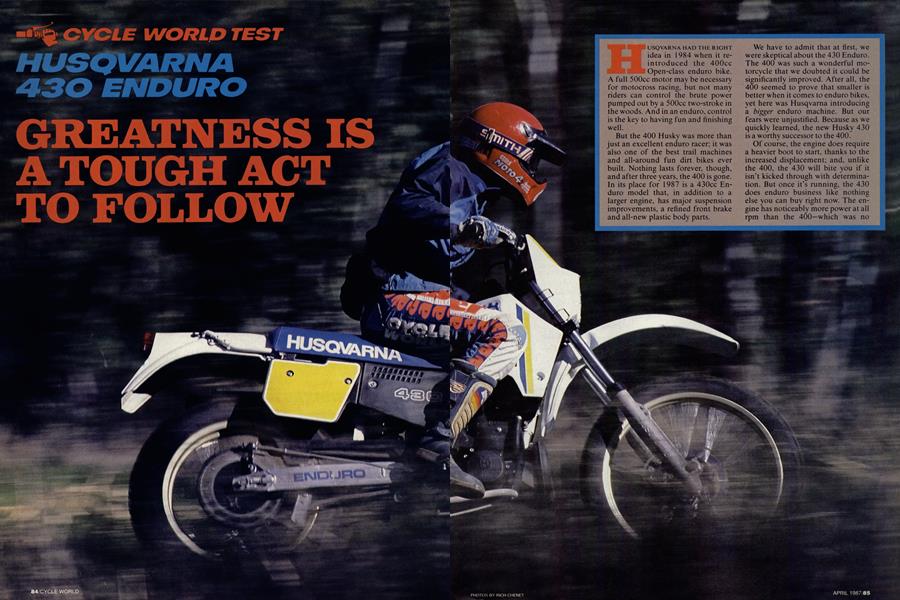

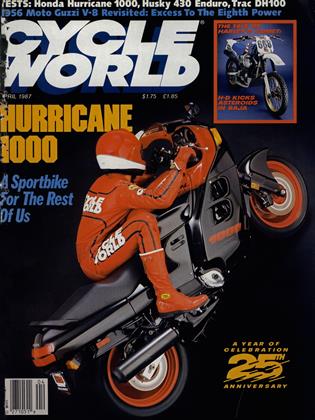

HUSQVARNA 430 ENDURO

CYCLE WORLD TEST

GREATNESS IS A TOUGH ACT TO FOLLOW

HUSQVARNA HAD THE RIGHT idea in 1984 when it reintroduced the 400cc Open-class enduro bike. A full 500cc motor may be necessary for motocross racing, but not many riders can control the brute power pumped out by a 500cc two-stroke in the woods. And in an enduro, control is the key to having fun and finishing well.

But the 400 Husky was more than just an excellent enduro racer; it was also one of the best trail machines and all-around fun dirt bikes ever built. Nothing lasts forever, though, and after three years, the 400 is gone. In its place for 1987 is a 430cc Enduro model that, in addition to a larger engine, has major suspension improvements, a refined front brake and all-new plastic body parts.

We have to admit that at first, we were skeptical about the 430 Enduro. The 400 was such a wonderful motorcycle that we doubted it could be significantly improved. After all, the 400 seemed to prove that smaller is better when it comes to enduro bikes, yet here was Husqvarna introducing a bigger enduro machine. But our fears were unjustified. Because as we quickly learned, the new Husky 430 is a worthy successor to the 400.

Of course, the engine does require a heavier boot to start, thanks to the increased displacement; and, unlike the 400, the 430 will bite you if it isn’t kicked through with determination. But once it’s running, the 430 does enduro business like nothing else you can buy right now. The engine has noticeably more power at all rpm than the 400—which was no slouch—and is especially strong in the mid-range. If the throttle is twisted wide-open when the engine is in the middle rpm ranges, the front wheel either leaps into the air or at least gets very light, and the bike moves out quickly, no matter what gear the six-speed transmission might be in. At very low revs, the engine growls down to a crawl like a Caterpillar tractor—and with almost as much climbing power. Yet the 430 revs freely and produces a good amount of horsepower at high rpm.

In all, it’s as perfect an enduro engine as you could reasonably imagine. We rode our test 430 in the wilds of Baja, across the wide-open expanses of the Mojave Desert and on the tight trails of local mountains, all with the stock final gearing; and nowhere did we find conditions that the Husqvarna 430 engine couldn’t conquer in grand style.

Not only is the 430 faster and torquier than the 400, but it’s smoother-running, as well. Mainly due to its use of a lighter connecting rod, the 430 gives off a bit less engine vibration than the 400. The motor also incorporates other changes, such as a primary-drive case fabricated from aluminum instead of magnesium (which supposedly eliminates the corrosion problem that occurred inside the waterpump cavity on the 400 engines), as well as a few improvements to the kickstart lever and its little rubber bump pad. Altogether, these changes might seem insignificant, but they make the Husky an easier bike to live with.

In addition, the 430 has a largerdiameter clutch, which, for the most part, is an improvement over the 400’s fragile clutch. The engagement span is much wider than on Huskys of the past, which makes the clutch pull easier and the engagement more gradual; but the clutch on our test bike insisted on increasing its freeplay every time it was slipped or slightly abused, and would not return entirely to normal once the clutch cooled off.

Okay, so give the 430 low marks for clutch durability. But this bike will get no such demerits when it comes to suspension quality; the 430 absorbs the thumps and bumps of fast olf-road riding better than anything this side of a hand-prepped factory enduro racer. On last year’s 400, the fork and shock worked well at flat-out racing speeds but tended to be harsh at slower speeds; the 430 suspension, though, is plush at all speeds and over all bumps. The fork has a new damper arrangement, and the rear suspension has a revised linkage that allows the use of a much softer spring and lighter internal shock damping.

When you first sit on the 430 and do the traditional, all-important suspension test—bouncing the front fork up and down—you just know that the front end is way too soft. But out on the trail, the fork behaves magnificently, gobbling up the nastiest bumps, holes and whoops with ease. The rear end is just as wonderful, allowing the rider to pass over ridiculously rough terrain usually without even needing to stand up. And the 430 does all this while always exhibiting amazing straight-line stability.

On most types of terrain, the 430 also steers easily and precisely. But when the bike gets in sand, the fork’s softness works against it. The front wheel tends to “tuck under” in tight turns, and the bike weaves around a lot at higher speeds. We remedied much of this by cutting two full coils from each fork spring and reshaping the spring’s end. This shortened each spring by about an inch, thus increasing the spring rate. We made spring spacers from thick-wall PVC plastic pipe, and tried different lengths to achieve various amounts of spring preload. We finally decided on 2mm preload, which resulted in the best compromise between steering precision and ride quality.

Adding to the 430's overall comfort is a wider, longer seat that allows all-day rides to be no problem. The seat lets the rider move fore and aft easily and doesn’t foul his legs when he stands on the 430's new and stronger footpegs.

Another welcome addition is a stronger front disc brake. Its dual-piston caliper floats on the fork leg, and the disc rotor is solidly mounted (rather than floating as on the 400) to a lighter front hub. An easy, two-finger pull on the front brake lever is all that’s needed for most situations. The brake furnishes good feel, with powerful but progressive stopping power. And although the large, 6.3inch rear drum brake is the same as on previous Huskys (except for a lighter hub and more easily accesible sprocket bolts on the 430), it delivers more than adequate braking performance on the 430.

Altogether, the major changes Husqvarna has made to the 400 when upgrading it to a 430 have resulted in a better motorcycle, but there are a couple of small but annoying problems that the company continues to ignore year after year. One is the sidestand spring, which is located on the bottom side of the stand where it constantly gets broken or knocked off by rocks and tree roots. If the spring were moved to the top side of the stand, it would last more than a few miles. Then there’s the speedometer cable, which, traditionally, seldom lasts more than a few miles on a Husky before getting caught in the front tire and ripped out of the drive unit. And for almost 20 years, the kill buttons on Husqvarnas have been shorting out.

Cagiva/Husqvarna deals with these deficiencies in an unusual way: by simply removing the speedo cable and disconnecting the kill button on magazine test bikes. So while the 430 now has a nice little odometer in place of a full speedometer, we don’t know how well it works (although the odometer bracket cracked due to vibration during the test). It’s about time the same engineers who have designed one of the world’s finest enduro motorcycles tackle these nagging little problems and put them in the past.

Despite those little glitches, though, the 430 still is the best Openclass enduro machine in existence— maybe the best all-around enduro bike of any size. It’s one of those rare machines that can make just about anyone who climbs aboard them a better rider.

HUSQVARNA 430 ENDURO

$3435

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialThe Best of Rides, the Worst of Bikes

April 1987 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeAmerican Style In France And Finland

April 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupLending History A Helping Hand

April 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

April 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

April 1987 By Alan Cathcart