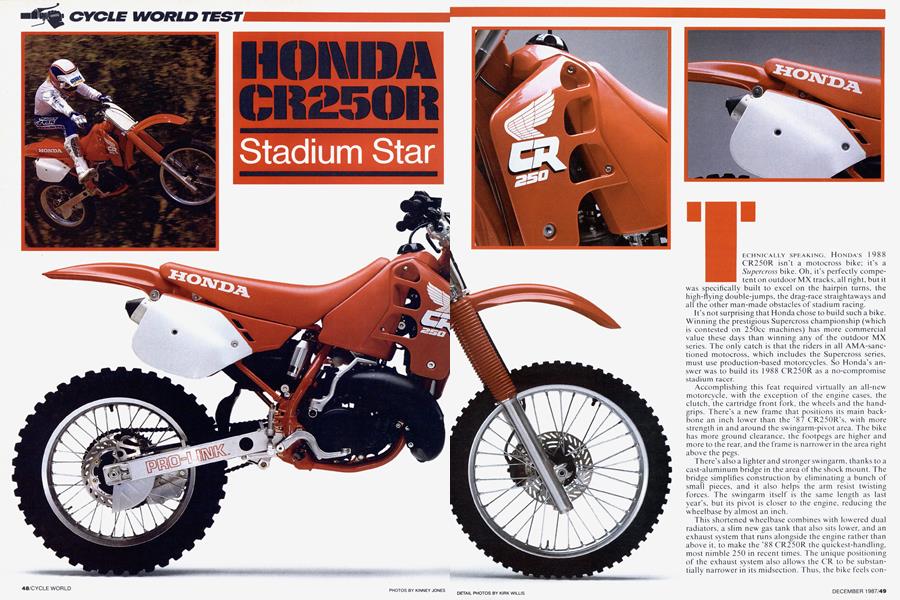

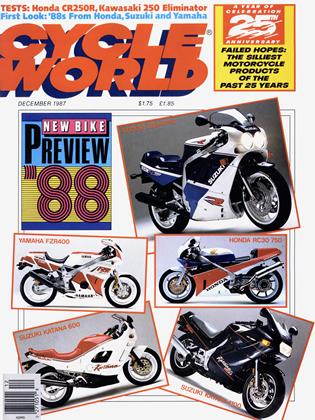

HONDA CR250R Stadium Star

CYCLE WORLD TEST

TECHNICALLY SPEAKING. HONDA'S 1988 CR250R isn't a motocross bike; it's a Supercross bike. Oh, it's perfectly competent on outdoor MX tracks, all right, but it was specifically built to excel on the hairpin turns, the high-flying double-jumps, the drag-race straightaways and all the other man-made obstacles of stadium racing.

It’s not surprising that Honda chose to build such a bike. Winning the prestigious Supercross championship (which is contested on 250cc machines) has more commercial value these days than winning any of the outdoor MX series. The only catch is that the riders in all AMA-sanctioned motocross, which includes the Supercross series, must use production-based motorcycles. So Honda’s answer was to build its 1988 CR250R as a no-compromise stadium racer.

Accomplishing this feat required virtually an all-new motorcycle, with the exception of the engine cases, the clutch, the cartridge front fork, the wheels and the handgrips. There’s a new frame that positions its main backbone an inch lower than the '87 CR250R’s, with more strength in and around the swingarm-pivot area. The bike has more ground clearance, the footpegs are higher and more to the rear, and the frame is narrower in the area right above the pegs.

There’s also a lighter and stronger swingarm, thanks to a cast-aluminum bridge in the area of the shock mount. The bridge simplifies construction by eliminating a bunch of small pieces, and it also helps the arm resist twisting forces. The swingarm itself is the same length as last year’s, but its pivot is closer to the engine, reducing the wheelbase by almost an inch.

This shortened wheelbase combines with lowered dual radiators, a slim new gas tank that also sits lower, and an exhaust system that runs alongside the engine rather than above it, to make the ’88 CR250R the quickest-handling, most nimble 250 in recent times. The unique positioning of the exhaust system also allows the CR to be substantially narrower in its midsection. Thus, the bike feels considerably lighter than its 217 pounds, and it will change direction in the blink of an eye. Flicking the 250 into an Sturn or through a tight switchback requires very little effort on the rider’s part.

Amazingly, the CR also has improved straight-line performance. The front-wheel trail has been increased a tenth of an inch, and the solidly mounted handlebar now sits farther to the rear. These changes, with the help of the more-rearward placement of the footpegs, have eliminated most of the infamous CR headshake.

Still, the bike’s extreme sensitivity to any kind of input tends to make even experienced CR riders feel a little uncomfortable during the first few hours they ride it. The bike’s willingness to change direction instantaneously is always present, and the slightest movement or weight shift by the rider immediately changes the Honda’s flight path when it’s airborne.

But this very sensitivity is what makes the ’88 CR250R such a magical machine once the rider adjusts. It has the handling quickness that is essential to be competitive in stadium racing, and it simplifies the task for riders who have the talent to thrill the spectators with aerial acrobatics.

Obviously, a short, quick-handling bike like this one needs exceptional suspension to be manageable in the rough. And the new CR has no problems there, either. Previous C’Rs tended to lose their rear-shock damping after a few races; and the behind-the-tank location of the shock reservoir on the ’87 bike didn’t let it get much cooling air, so the damping would quickly fade. But the new bike’s Showa shock has compressionand rebound-damping rates that start out practically perfect and stay that way, due in part to the shock’s integral reservoir being placed on the right side of the bike where it can be cooled by the air. The rear end also has a new spring and revised linkage arms that alter the progression curve.

The rear end is really impressive when accelerating across hard-edged potholes, a condition that normally poses a problem for any rear suspension. But the CR handles those obstacles with style. The rear wheel follows the ground with precision, and there’s no kick or sidehop or other heart-stopping reaction to crossing cobby terrain under power.

Up front, the Showa cartridge fork that was state-of-theart in 1987 is slightly improved for ’88. It uses higherquality, slipperier bushings, and a bit more compression damping. Stififer fork springs are also standard and should be adequate for most riders up to Pro level. Pro riders, however, may need stififer springs, for they’ll probably be able to ride across rough ground and sail off of jumps fast enough to bottom the fork too often.

Complementing this stadium-racer chassis is a potent engine with a mile-wide powerband. It pulls more strongly on the bottom than the ’87 motor did, partly the result of an exhaust-port-control mechanism that opens its valves at a lower rpm. The exhaust port itself is larger, which boosts power by letting the engine rev higher, and a lighter crankshaft lets it rev faster. A Nikasil-coated aluminum cylinder bore is home for a more durable piston, while a new connecting rod has a larger big-end bearing. The midmounted exhaust pipe does its bit to increase the engine's power and powerband, as well, while its thick outer wall helps silence exhaust noise and ward against crash damage.

The end result of all this is a bike that feels nothing like a typical 250. Its exceptional narrowness and low center of gravity give the rider the impression he is riding a crisphandling 125, while the low, sharp exhaust bark and earthmoving power output send messages that tell him he’s on an Open-class bike. Indeed, the CR250R rockets out of the turns like a big-bore racer, usually with its front tire just skimming the ground and the engine groaning along at lower rpm.

Thanks to a five-speed transmission with all-new ratios, none of this Open-class-style power is wasted. First gear is taller than its ’87 counterpart, but the wider powerband makes it feel lower. Second and third are slightly lower than before, while fourth and fifth are taller. What’s important, though, is not the gear-ratio numbers, but rather what those numbers mean. And on the '88 CR250R, they mean that there is never any bogging or lagging, for the engine is always in its powerband—unless, of course, the rider is a couple of gears too high or too low for any given situation. The gearbox also shifts precisely and with little rider effort. Second-gear starts seem to work best, and the clutch engages smoothly and progressively as the CR churns off the starting gate.

Charging toward the first turn, the rider can easily move fore and aft on the extremely narrow CR. Shifting his weight to the front of the bike for a tight turn is equally easy, for the gas tank is so slim and so low that he can slide as far forward as he wants without climbing atop the tank or spreading his knees far apart.

Once into a turn, the CR will take virtually any line the rider chooses. It allows excellent control while either riding the high berm or diving in tight. And changing lines mid-way through a turn is kid’s stuff on this bike.

Despite being built as a Supercross specialist, then, the

new CR250R just may turn out to be the perfect racebike, a machine that will need no more than a tire change to be fully competitive in all sorts of motocross racing all around the country, indoors, outdoors or anywhere in between. It’s one of those rare machines that lets the rider concentrate more on the act of winning and less on the act of operating the thing.

In all fairness, however, we can't yet say that the CR250R will be the best 250-class motocrosser of the year. Our brief test rides on the '88 Yamaha YZ250 and Cagiva 250MX have indicated that they are very serious contenders, and we’ll have sampled the newest Kawasaki KX250 and Suzuki’s Hannah-replica RM250 before this issue hits the newsstands. So the Honda appears to have no shortage of competition for 1988.

But we will say this: For any of those other 250s to outgun the Honda for top spot this coming year, it will need to be one absolutely killer motocross machine.

HONDA CR250R

$3298

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialIdol Speculation

December 1987 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeService Bulletins

December 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsDesmo Fever

December 1987 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1987 -

Roundup

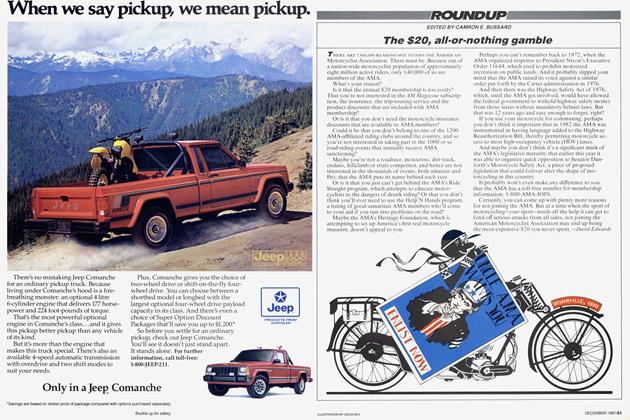

RoundupThe $20, All-Or-Nothing Gamble

December 1987 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupRallying In the Rockies

December 1987 By Bill Stermer