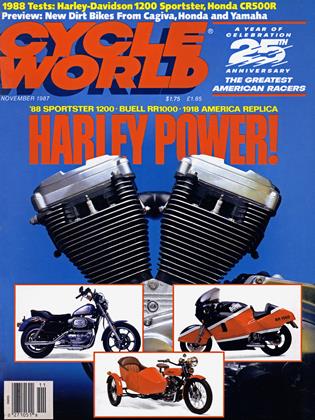

1988 HARLEY-DAVIDSON SPORTSTER 1200

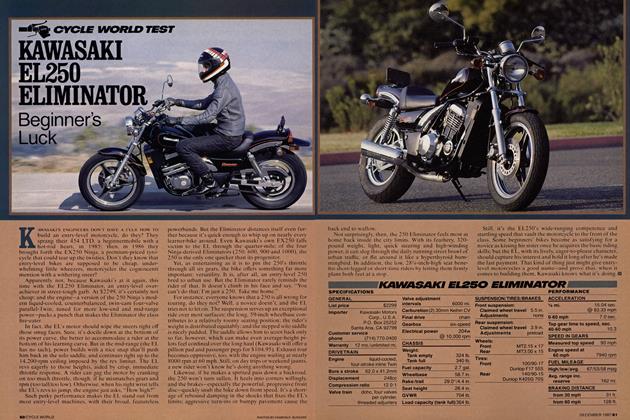

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Bigger—and better—than ever

SOME THINGS NEVER CHANGE. IN 1957, HARLEY-DAVidson first started building Sportsters. Now, 30 years later, Harley is still building Sportsters. Just as in the beginning, a Sportster is a big, fast, rowdy motorcycle, a machine that’s all bones and muscle and gristle, and no fat at all.

But while things may not change, that doesn’t mean they remain exactly the same. For 1988, an extra lOOcc of muscle have been added to Harley’s top-of-the line XL, making it a 1200. That increase, along with other updates, has produced the strongest-running production Sportster at least since the limited-production XR1000 of 1983, if not ever, and brought some new civility in the bargain. But a few problems that have burdened XL Harleys for years still remain, leaving the Sportster... a Sportster, for better and for worse.

What makes this year’s biggest XL special is its new 1200cc (or 74 cubic-inch) engine. By borrowing the 3.5inch cylinder bore of their 80 cubic-inch Big Twins, Harley engineers have brought Sportster displacement to a new high without lengthening the long, 3.812-inch stroke that’s been in use since 1957.

This displacement increase has been held in the Harley engineers’ bag of tricks for several years; they could just as easily have incorporated it into the 1986 1100 Sportster, but hesitated because of the bike’s four-speed gearbox. Sized for a considerably less-potent 883cc engine back in the 1950s, this gearbox was thought unlikely to appreciate the extra torque that 1200cc of Evolution V-Twin could provide. But several years of testing convinced the engineers otherwise; so, for 1988, we have the 1200.

Whatever its piston size, the Sportster engine retains the rest of its design intact. A 45-degree V-Twin, it is Harley’s only engine with unit construction, meaning that the gearbox (driven by a three-row primary chain) is integral with the crankcases. As with all Harley engines, the cylinders are not offset relative to one another, so a fork-and-knife connecting-rod arrangement is mandatory; one rod has its big end spread out into a U-shaped yoke that the other’s rod big end can nestle in. There are no counterbalancers or offset crankpins to reduce vibration; no one thought of such a thing in 1957.

On the righthand side of the engine, no less than four camshafts open the valves via long pushrods, a design that can only be explained by the Sportster’s derivation from Harley’s earlier K-model flathead. This is an old engine.

But while the Sportster's original blueprints may have faded, Harley has been busy bringing the engine into the modern world. So much has been changed over the last few years that only a few parts interchange between this year’s engine and one from 1957. The aluminum heads and cylinders are of Harley’s “Evolution” design, only slightly modified from those that rest atop Big Twin crankcases. Their compact combustion chambers and efficient ports explain how Sportster performance has improved, even while noise laws have required ever-stricter muffling.

The clutch and gearbox, too, have been updated over the last few years, reducing the effort needed to pull the clutch lever, and at the same time hiding away the alternator behind the clutch. And this year sees another important change: Both the 883 and the 1200 Sportsters now breathe through a 40mm Keihin constant-velocity carburetor. Basically the same carb used on, Kawasaki’s KL650R dual-purpose Single, the Keihin brings the dual benefits of precise fuel/air mixing and light throttle effort to an American motorcycle. It and the big pistons are this year’s contribution to the improvement of a classic American engine.

Riding the Sportster emphasizes the combination of the new and the old. The seating position is unusual, not chopper or standard or sport. The footpegs are high, and just forward of the front edge of the seat. The seat itself is fairly low, and the buckhorn handlebar places your hands high and back. The combination is almost like the sit-upand-beg posture demanded by 1960’s British bikes fitted with American-market high bars: but the low seat on the Sportster makes the position cramped. The bike would be more comfortable and sportier with the pegs back eight inches, or more comfortable and choppier with the pegs forward a foot or so. Either would be preferable.

There are no such glitches with the 1200’s engine, which fires quickly when cranked by the electric starter— but only when the enrichener circuit on the Keihin carburetor is engaged. Yes, this new carb doesn’t use the traditional Harley choke; so, unlike previous Sportsters, the 1200 won’t flood if the choke/enrichener knob is left open more than a few seconds. Lean, low-emissions jetting, however, requires the use of the enrichener for the first mile or so until the engine warms up.

Then, the 1200 impresses with its abundance of power. It accelerates hard from low rpm, and delights in being short-shifted. This performance is highlighted by superb top-gear roll-on acceleration, as verified by our thirdwheel tests. The 1200 leaps from 40 to 60 mph in 3.6 seconds, and from 60 to 80 mph in 3.9. There are 125horsepower, four-cylinder superbikes that don’t do much better. And around town, the smoothness of the power delivery is especially impressive. The 1200 does vibrate, but the vibration is only intrusive at engine speeds much above 3000 rpm, and that range is rarely used in town.

Quarter-mile times also demonstrate the power of the new 1200. Its best run took 13.07 seconds, a time that was hindered by the lack of start-line traction provided by the rear tire. On a grippier surface, or with stickier tires, the 1200 would surely match or better the 12.88-second quarter-mile time of the XR1000, the quickest production Sportster we have ever tested.

Unfortunate, then, is that this power can’t truly be appreciated on the open road. A rebalanced crankshaft in the 1200 makes for a far smoother engine than the 1100 it replaces, but the smooth range of engine operation still only extends to about 57 mph in top gear. Up to that point the quaking and shaking of the Sportster engine are only charismatic, part of its appeal. But above that speed the buzzing felt in the seat and footpegs is annoying and uncomfortable. The worst range is from 60 to 65 mph, where the vibration electrifies the seat; go a little faster, and the vibration diminishes a little, but only a little.

This is the strongest showing of the Sportster’s 1950s’ heritage, and should be the next problem that Harley’s engineers attack. A five-speed gearbox with a tall top gear to slow engine speed on the highway would help. In the meanwhile, concerned owners might think about installing a bigger countershaft sprocket; the 1200 engine can certainly pull taller gearing.

The Sportster’s chassis also contributes to the bike’s classic feel, but with modern touches. No trendy 16or 17inch front wheel here; instead, the front wheel measures 19 inches, just as God, the Queen and anyone else who had anything to do with big 1960s roadburners intended. Combine that big front tire with conservative steering geometry, and you might expect a two-wheeled train, sacrificing agility for unassailable stability. Well, the 1200 is stable, but it also turns nicely. Attribute that to the leverage provided by the high and wide handlebar, and to the 1200’s 470-pound dry weight, which makes it the lightest open-class production bike in existence.

Actually, the 1200 is quite at home on a twisty backroad. The torquey engine pushes the big Sportster hard away from corners, and its competent chassis can snake through them quickly. The 1200 runs a little shy of cornering clearance on the right-hand side, and feels a bit short of spring rate and damping when ridden aggressively through most corners; but by the time you reach that point, you have to be riding hard. So this isn’t a bike that will be embarrassed by a modern sportbike on a stretch of twisties, even if it’s not quite up to the latest standard.

Of course, more and more, hardware on Sportsters, and Harley-Davidsons in general, measures up. A few years ago a Sportster clutch was most useful as a tool for sadistic left-handers wishing to develop a deadly hand-shake; now it operates with reasonable pressure. The throttle used with the new CV carburetor is a quick-turn, low-effort item, and even the hold-down-for-flasher turnsignal switches can be replaced by the international rocker-style version from Harley’s accessory catalog. Only the front brake remains high-effort, and that from a deliberate design philosophy (one we keep hoping Harley will change).

So, in the end, it’s fairly amazing how far Harley has taken a 30-year-old design. The 1200cc Sportster is still a big, fast, rowdy motorcycle, even if some definitions of “big” and “fast” have transcended it. It’s a Sportster that’s better in every measurable way than its predecessors. It’s certainly not a perfect motorcycle, but it’s still a very good motorcycle.

And for a machine bearing the Sportster name and look, with all the character and charisma those two things carry, being perfect may be a much less vital goal than simply being a ... a Sportster.

1988 HARLEY-DAVIDSONSPORTSTER 1200

SPECIFICATIONS

$5875

PERFORMANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

November 1987 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1987 -

Roundup

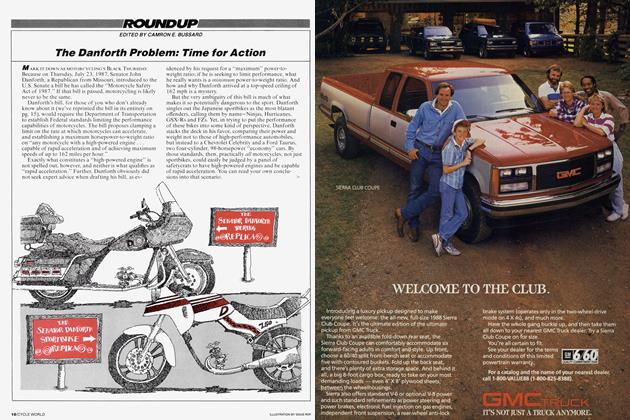

RoundupThe Danforth Problem: Time For Action

November 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Preview

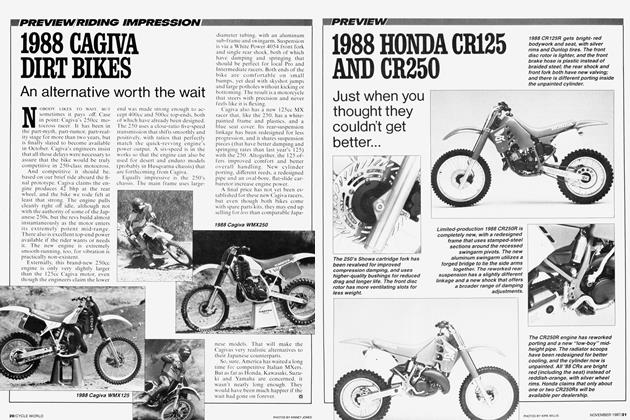

Preview1988 Honda Cr125 And Cr250

November 1987 -

Preview

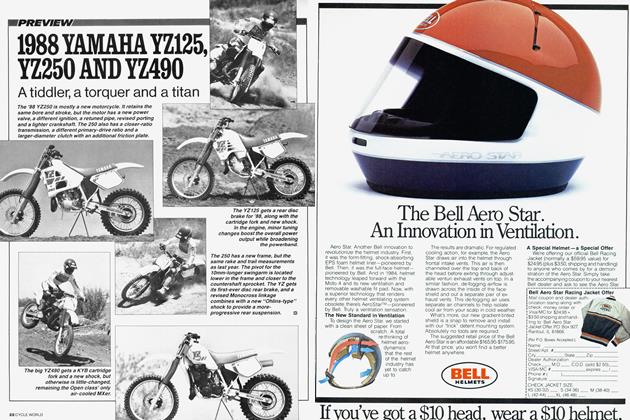

Preview1988 Yamaha Yz125, Yz250 And Yz490

November 1987 -

Features

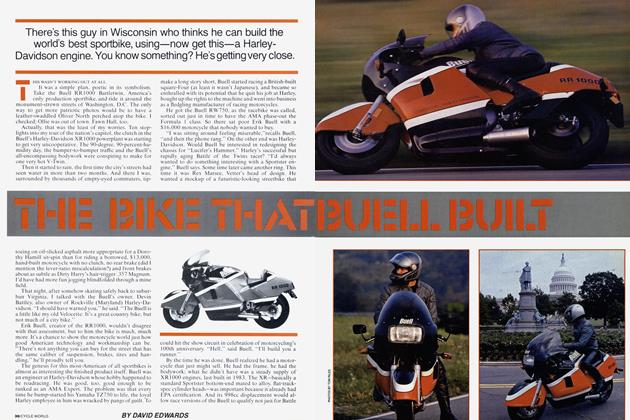

FeaturesThe Bike That Buell Built

November 1987 By David Edwards