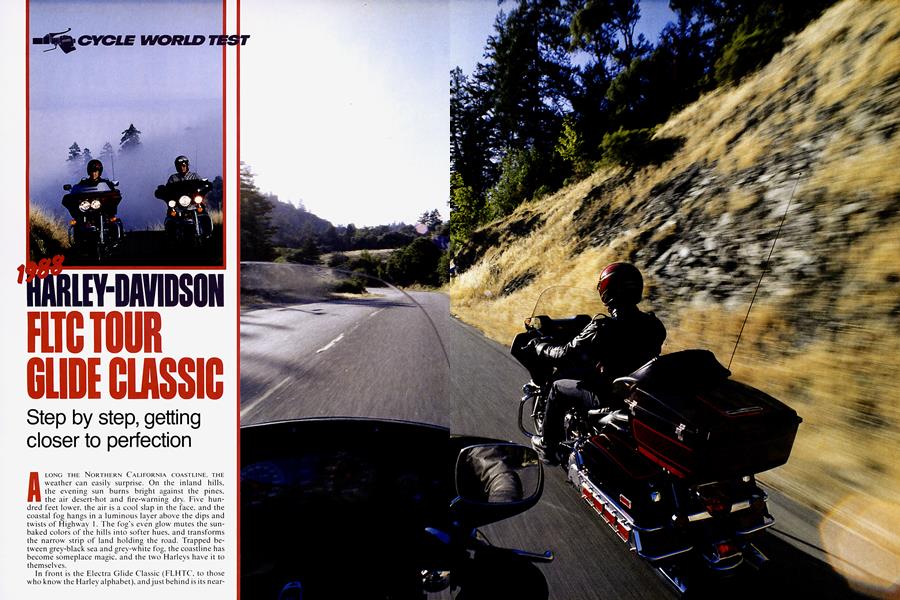

1988 HARLEY-DAVIDSON FLTC TOUR GLIDE CLASSIC

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Step by step, getting closer to perfection

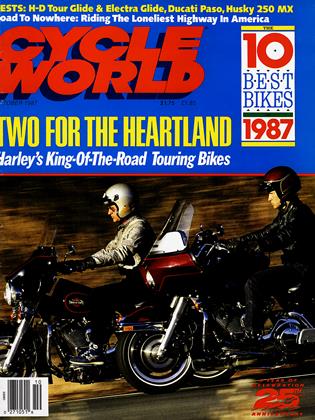

A LONG THE NORTHERN CALIFORNIA COASTLINE, THE weather can easily surprise. On the inland hills, the evening sun burns bright against the pines, the air desert-hot and fire-warning dry. Five hundred feet lower, the air is a cool slap in the face, and the coastal fog hangs in a luminous layer above the dips and twists of Highway 1. The fog’s even glow mutes the sunbaked colors of the hills into softer hues, and transforms the narrow strip of land holding the road. Trapped between grey-black sea and grey-white fog, the coastline has become someplace magic, and the two Harleys have it to themselves.

In front is the Electra Glide Classic (FLHTC, to those who know the Harley alphabet), and just behind is its nearidentical twin, the FLTC Tour Glide Classic. Their riders are having fun, at a pace faster than most touring riders would choose. The rhythm is set: charge hard out of the turns in third or fourth gear, (the acceleration from the newly revised Evolution engine is solid and quick), pick up speed and upshift down the short straights, then roll off and downshift to slow for the next corner. Brake only for the tightest turns. Lean until the undercarriage scrapes lightly, then hold that line through the corner.

TOUR GLIDE CLASSIC

The road unreels behind the Harleys quickly, but the riders are surprisingly relaxed; these 750-pound behemoths, carrying a week’s worth of gear, are stable and confidence-inspiring. They can be banked into the corners quickly, and the only real concern is not to stick the floorboard mounts so firmly into the pavement to unweight a wheel. Despite the pace, their riders are able to appreciate the play of fog-filtered light over the rugged coast.

If a Harley touring bike can be this successful at something as unlikely as playing roadracer down the Coast Highway, it can be superb at the more expected task asked of it the next day. It is a cover-the-miles-day, a time to keep the dials on the odometers spinning. The Tour Glide is aimed down interstate concrete instead of twisty blacktop, a mission it likes a lot. The massive V-Twin engine rumbles away smoothly, and the rubber engine mounts prevent vibration from blurring the good view from the new convex mirrors. The radio is pulling in jazz from a San Francisco station, clearly and loudly enough that it can be heard at an indicated 75 mph. But most important, the Tour Glide’s rider is comfortable, his feet stretched out ahead, his butt resting on one of the best seats in motorcycling. In the next nine hours, the odometer will click off 475 miles, miles that will have left the FLTC’s rider without the aches and stiffnesses that too often accompany motorcycle touring.

As these, and other, rides showed, 1988 has seen Harley continue to refine its big touring bikes. This year, the improved FLTC surely sets some new standards for touring bikes. Just as surely, while some long-standing problems have been muted, Harley’s big tourer still could stand further improvement.

Strengths first: The FLTC's torquey Evolution V-Twin leaves the first impression. It's a wonderful engine, as refined a Twin as ever left Milwaukee. This year, the allaluminum, 1340cc powerplant has a new camshaft with more lift and duration, and revised carburetion. Harley engineers admit that the changes were serendipitous: The new cam profile was originally an attempt to meet California emission standards, and not a successful attempt, at that. But unexpectedly, the cam increased power over the engine’s entire operating range, giving (according to Harley) three percent more peak power, and six percent more peak torque.

Whatever the figures, this engine works, pulling smoothly and powerfully everyplace, and lugging down under heavy load to 1400 rpm in top gear without driveline snatch. Before the Evolution top end just a few years ago, Harley Big Twins would snap and cough under the same conditions. But this revised engine thumps and rumbles in convincing Harley style, and propels the Tour Glide down the road better than ever.

Beyond its engine, the FLTC's next great strength is its rider and passenger accommodations. This big Hog has a great seat. The shape is the same as on last year’s Tour Glide, but a slight increase in foam stiffness renders it even better for the long haul. A roomy riding position, combined with floorboards that offer multiple locations for your feet, make 500-mile days quite possible on this bike without your body feeling the least abused. And the passenger is as cradled as the rider. The rear seat is excellent, and the padding on the travel trunk (which is adjustable fore and aft an inch and a half) provides comfortable back support.

The FLTC’s third charm is its handling—above a rolling speed, at least. The basic chassis dates back to the 1980 Tour Glide, which was the first of the new products that brought Harley into the era of modern motorcycling. The most important new elements of the chassis were the rubber engine mounts that isolated the heavy vibration of the engine from rider and hardware; but along with the rubber mounts came a stiff s if heavy) frame with unusual steering geometry. The steering head is set at a reasonably steep 26 degrees, but the triple clamps position the fork legs behind the steering head, and at a three-degree more rakish angle.

The end result is 6.2 inches of trail, and steering that is both reasonably light (especially with the wide handlebar) and reassuringly stable.

No one will ever mistake a Tour Glide for a roadracer (no nlatter how much metal is left behind on Highway 1 ), but it still handles twisty roads with aplomb. Cornering limits are dictated not by tire traction but by ground clearance. That limit is relatively low (even with the air suspension pumped up) by sportbike standards, but it still allows more lean than most touring riders will ever use.

More important is the machine's straight-line stability. Despite its willingness to turn, the FLT is by no means nervous. It stays on course without much feedback from its pilot, leaving the rider free to sightsee without having to make constant course-corrections.

Along with these major strengths, there are many impressive details. Hand controls on Harleys no longer belong in the weight room at Gold’s Gym; the Tour Glide’s brakes, clutch and throttle respond to reasonable efforts. The friction screw on the throttle housing is a useful alternative to an electronic cruise control; it won’t keep the FLTC at as constant a speed, but it allows throttle position easily to be varied on a busy highway, while still eliminating the need for the rider to hold constant pressure on the twistgrip while cruising. All important functions of the radio/tape player can be controlled easily from handlebar switches. Overall fit and finish are generally good, with some of the best chrome to be seen on a production motorcycle. All told, most of the details, as well as the basic hardware, show the results of years of refinement.

That makes the few remaining problems and faults more noticeable; because even though the Tour Glide is an excellent, vastly improved touring bike, it still could be better. And the first upgrade should entail the fairing and related wind control. Just as the Tour Glide’s seat sets standards among touring bikes, so does its fairing set a standard: It’s perhaps the worst on any factory full-dress tourer.

To begin with, the frame-mounted fairing is too far forward of the rider, and is fitted with a narrow, short windscreen. The fairing's quality of manufacture and finish has been improved (the small storage pockets now have nicely trimmed edges, instead of jagged fiberglass), but under certain conditions, it can batter you with turbulence. It’s not too bad at 65 mph with no side winds and an open-face helmet; then, the vortexes coming off the sides of the windscreen only lightly buffet your cheeks. But go faster, or ride with a good sidewind blowing, and the wind slaps at your face, verging on the painful under the worst conditions. And with a full-face helmet, the turbulence rattles the faceshield loudly enough to make earplugs mandatory. The FLTC’s fairing needs to be closer to the rider, or taller and wider—or in any case, different. (In fact, the classic Electra Glide handlebar-mount fairing works better; see

the Electra Glide riding impression below).

While the Tour Glide fairing makes no attempt to keep wind or weather off its rider’s legs, that—at least in the dry—is probably for the best. The 1340cc V-Twin radiates a fair amount of heat, and at highway speeds, the passing breeze air-cools the rider’s legs. Get stuck in traffic on a hot day, though, and the engine’s heat can be felt, particularly basting the right leg that’s close to oil tank and exhaust pipe. Otherwise, the Harley is cooler for its rider than most of the liquid-cooled Japanese tourers, but at the cost of foul-weather protection.

Also falling short of class standards is the Tour Glide’s luggage. The top trunk is an inch taller this year, the better to store two full-face helmets. But whereas the trunk is now molded in an improved, odor-free material, the saddlebags are still made of a fiberglass that leaves a strong resin smell that permeates anything left in them. We’ve had other Harley touring bikes around for months, and observed no noticeable diminishment of the resin odor.

In addition, ever since the Tour Glide’s introduction in

1980, the right bag has suffered from a volume reduction almost to glove-box dimensions by an internal relief that allows room for the battery (which projects out from the oil tank, filling space normally devoted to luggage). And although the locks and latches have been simplified and improved for ’88, they’re still more bothersome to use than the single-key system and over-center latches found on Gold Wings and the like.

Finally, our last major quibble with the Tour Glide is its low-speed handling. While none of the larger Japanese touring bikes are what you would call agile at a walking pace, the Tour Glide feels particularly clumsy during lowspeed maneuvers.

But even though the Tour Glide has room for improvement, it still ranks as one of the best touring bikes on the market. For simply racking up highway miles on fairweather days, very few motorcycles can compare; with the exception of wind control, it is at least as comfortable on the freeway as anything else on two wheels. And the VTwin engine rumbles along entertainingly these days without allowing vibration to annoy its rider; the rubber engine mounts really do their stuff. Granted, the Tour Glide would be completely out of place in Europe (it doesn’t go fast enough) or Japan (maneuverability and low-speed handling would penalize it there), but it’s right at home on American roads.

And that’s exactly where it belongs, be it the Pacific Coast Highway or the Blue Ridge Parkway or Interstate 80. This is a bike meant to go places, comfortably and in grand Harley style. It does that well now. With just a few more improvements, it would do it better than any of its competition, and fully earn one of the traditional nicknames for full-dress Harley touring rigs: King of the Highway. ga

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialOh, Why, Tell Me Why

October 1987 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeSherlock And the Golden Hour

October 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1987 -

Roundup

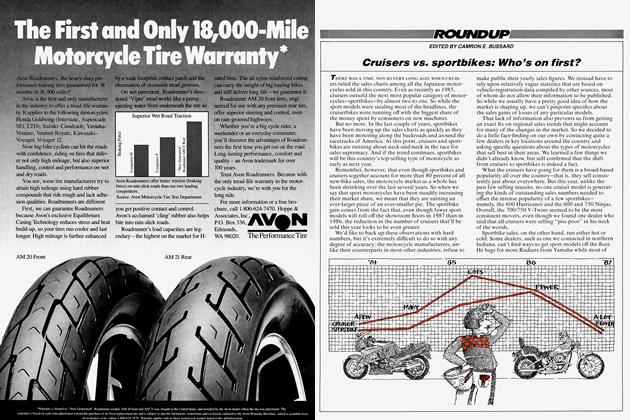

RoundupCruisers Vs. Sportbikes: Who's On First?

October 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Sdr Rocket

October 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupAprilia's Expansion Plans

October 1987 By Alan Cathcart