BEST FOOT FORWARD

Does the key to motorcycling’s future lay in its past?

PAUL BLEAZARD

YOU'LL FIND THEM IN ENGland. Of course. They're a little strange. Of course. And they think they've got a better way of building a motorcycle. Of course.

They are Feet-Firsters, a name derived from the kind of motorcycles these enthusiasts build and ride. And for those of you who don’t already know, a feet-first motorcycle is one that puts the rider in a semi-reclined seating position, similar to an auto-mobile driver’s stance, with his feet forward.

A dedicated Feet-Firster will be quick to tell you that conventional motorcycle designs are nothing more than glorified bicycles, with centers of gravity too high, aerodynamics too dirty and suspension/turning systems too primitive. There’s a better way to go, they’ll continue with the glassyeyed zeal of a brand-new religious convert, and for evidence they’ll point to the Honda Helix, the newwave scooter that has just been loosed on the land. Oh, they will tell you that the Honda Helix is a Johnny-come-lately on the feet-first scene and that it doesn’t go quite far enough, but that it’s a step in the right direction, at least.

So just what are the advantages to riding around with one’s toes leading the way? First off, Feet-Firsters claim there is no secret to the superiority of their preferred design; no magic or sorcery, just the logical application of basic physics as opposed to the dictates of convention, fashion and dyed-in-the-wool conservatism.

For one thing, the seating position can be much more comfortable than that of a regular motorcycle, especially if it involves a big enough seat and a backrest. Body weight is then supported by the buttocks and lower back, freeing the arms and feet to deal exclusively with the task of controlling the machine. Feet-Firsters are also quick to point out that all machines requiring delicate control at high speeds, such as jet fighters or Formula One racing cars, position

their operators in a semi-reclined position. The sole exceptions are racing motorcycles.

To allow this reclined seating position, a feet-first motorcycle needs a stretched wheelbase. This, in turn, allows the rider to be positioned lower, which is better for streamlining and for achieving a lower center of gravity. Also, Feet-Firsters have shown a fondness for wrapping their creations in wind-cheating bodywork, which lowers the drag coefficient even further while improving comfort and making the bike much more allweather practical.

“FFers” also place great importance on separating the steering

mechanism from the front suspension (as car designers have done for years), often employing hub-center steering to that end. The advantages of good hub-center designs are that they allow constant steering geometry, have built-in anti-dive properties, and require a bit less suspension travel, since valuable inches aren’t wasted through front-end dive during braking. And contrary to popular opinion, hub-center steering is not much heavier than most telescopic forks, and unsprung weight is about the same.

Perhaps the most famous feet-first bike of recent times was the Quasar, a swoopy-looking device of the late 1970s powered by a 40-horsepower, French-made Reliant four-cylinder engine (a 1984 version used a Kawasaki 1300 Six as a base). Due to a host of problems—none of them related to the design of the machine—the Quasar never got off the ground; but that hasn’t deterred a host of FF followers from cobbling together their own versions of what they see as the ideal motorcycle design.

As modern and revolutionary as feet-first motorcycles may seem, they’ve been with us almost from the beginning of motorized, twowheeled history. As early as 1909, a Mr. Renouf designed a feet-first motorcycle for the James company that

boasted hub-center steering, in the same year, the Wilkinson company of Great Britian (better known for its swords and razor blades) went into production with its 676ce, four-cylinder Touring Autocycle (TAC), which by 1911 had grown to 844cc and sprouted a bucket seat and steering wheel. Later versions dropped the wheel in favor of a handlebar, but the Touring Motorcycle (TMC) retained the bucket seat and an unrivaled reputation for comfort.

Contemporary with the Wilkinson was the Militaire from the good old US of A. A variety of models was produced, in eight different cities, but the most radical was a 4-horsepower,

480cc Single of 1912, of which probably less than 100 were made. This “Underslung” machine (as it was known) had a bucket seat, a steering wheel and wooden spokes, in addition to the elliptical rear suspension and the retractable, mini stabilizer wheels common to most Militaires.

In this field, at least, the First World War seems to have been more of a hindrance than a help to innovation; but in 1921, two of the most extraordinary motorcycles ever built went into production on opposite sides of the Atlantic. From the ruins of a humiliated and inflation-torn Germany emerged the Megola. Designed by Fritz Cockerell, this 640cc machine utilized a five-cylinder, radial engine not unlike those used in WWI biplanes. What was so distinctive about the Megola was that the engine was built into the front wheel. There was no clutch or gearbox, and the bike was either push-started or coaxed into life on its centerstand by “kicking with the heel into the spokes of the front wheel.”

The Megola was not just a weird one-off, but a very successful production machine of which nearly 2000 were made, including racing versions capable of a top speed of 85 mph. Thanks to a low center of gravity, these front-wheel-drive bikes had excellent road-holding qualities, and the Munich-based company’s works team won many races. To change the gearing, the mechanics simply fitted a larger or smaller front wheel.

Over in “the new world,” American J. Neracher was setting new standards of handling with his moldbreaking Ner-a-Car. The earliest models used a 283cc two-stroke engine and an ingenious, infinitely variable friction drive to the rear wheel. The Ner-a-Car was the first motorcycle to combine the advantages of hub-center steering with a low center of gravity. Many were built under license in England, where the design was improved with modifications to the steering and by the use of a 348cc Blackburne side-valve engine.

Ner-a-Cars were intended as touring machines, but were versatile enough to take the team prize in an early endurance rally, England’s 1000-mile Stock Machine Trial of 1925. The one thing missing from the standard model, however, was some bodywork to give the rider protection from the elements.

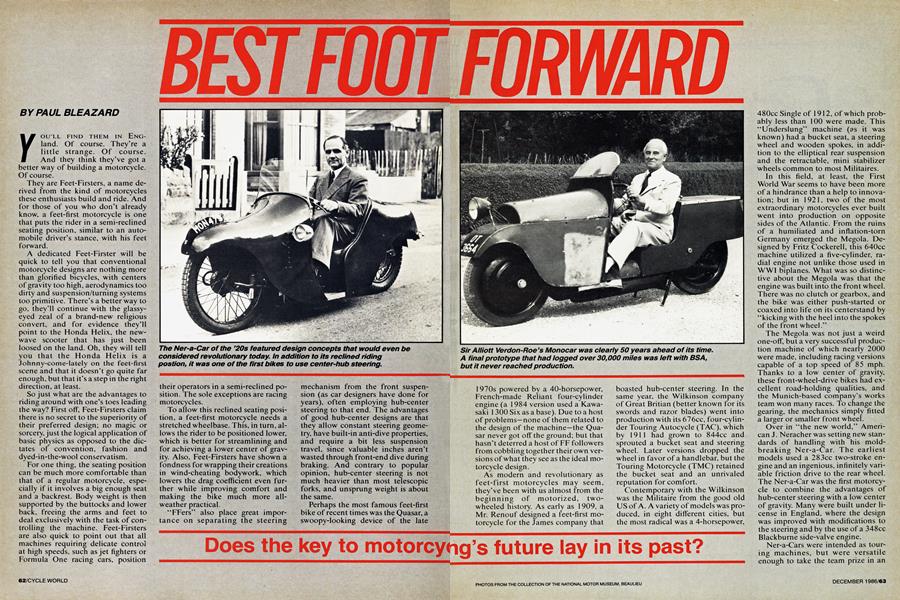

It was Sir Alliott Verdon-Roe, a British genius best known for his flying exploits, who, with his Monocar, fitted this final piece to the feet-first jigsaw puzzle. A.V. Roe, as he was better known, was the first Englishman to fly a powered airplane, and in 1912 was also responsible for the world’s first enclosed aircraft; so it was no surprise that he should have also designed the world’s first enclosed motorcycle.

Verdon-Roe’s aim was to produce what he called a “utility machine” for the everyday rider; one which would enable its owner to go about his business in safety, warmth and comfort wearing only normal outdoor clothing, while carrying a reasonable amount of luggage.

Dissatisfied with his attempts to modify existing motorcycles by adding leg shields and other fittings, Verdon-Roe decided to design and build his own machine. His first attempt used a two-and-a-half-horsepower engine and was so fully enclosed that it actually had springloaded side doors for his feet. The machine was very stable once it got moving, but the engine had the unfortunate habit of seizing solid.

Following extensive modifications

to this first, small-wheeled vehicle, Verdon-Roe designed an entirely new and more advanced model in 1926, which received extensive coverage in the UK press of the day. Sir Alliott called his creation the Mobile, but to everyone else it was the Avro Monocar, and it was clearly half a century ahead of its time. It had a swingarm mounted at each end of the extremely low-slung, pressed-steel chassis, and 26-inch-by-3.5-inch wheels, in spun aluminum, were fitted on stub axles, car-style. Both wheels were deeply dished, with huge-for-1926, 10-inch drum brakes. The front wheel also contained two vertical coil springs for suspension. This time, the engine was a 350cc Villiers two-stroke, and power to the rear wheel was delivered via a threespeed gearbox and a worm-drive shaft.

Seat height of the Monocar was just 14 inches. Its all-aluminum bodywork could be removed in a matter of seconds thanks to the use of “aero-motor cowling clips,” and it incorporated a fuel tank under the “hood” and a large locker, or “trunk,” over the rear wheel.

By 1930, the Monocar had covered more than 30,000 trouble-free miles, most of them logged by Verdon-Roe himself on his frequent, 500-mile round-trip journeys from Southhampton to Manchester and back, invariably wearing nothing more than normal pedestrian clothing. Writing

in The Motor Cycle some 20 years later. Roe recalled, “Shortly after producing this machine, it was left at the BSA works in the hope that they would put a machine of this type on the market; but the time for doing so was not considered opportune.”

It seems the motorcycle industry then, as now, was reluctant to market any radical-looking, feet-first machines. But that doesn’t mean the support for these bikes hasn’t been there. In 1943—just six years after designing the 500cc Speed Twin that would evolve into one of the most beloved conventional motorcycles of all time, the Triumph BonnevilleEdward Turner presented a paper to the Institution of Automobile Engineers on “Post-war Motor Cycle Development.” After outlining ail the inherent advantages of a powered two-wheeler, Turner set down a description of the bike he thought would increase the motorcycle market;

1. Be economical to buy and operate.

2. Have the greatest practical weather protection.

3. Be infinitely more silent, both as regards exhaust and mechanical noise, than has heretofore been accepted as standard.

4. Start easily and idle with certainty.

5. Be easy to clean and have as much of the “works” enclosed as is practicable.

With these criteria. Turner was largely echoing the thoughts of A.V. Roe some 20 years before; so it is not too surprising that his vision of “the extreme limit of motorcycle development” looks remarkably like a stylized version of the Monocar, albeit with a conventional front fork.

Turner’s wisdom and that of the early feet-first apostles may have been largely lost on the motorcycle industry; but Italian scooter builders put those five criteria to work with the venerable Vespa, a timeless design that has sold ten million units since 1948, making it the third most produced motor vehicle ever, beaten only by the Model T Ford and the VW Beetle.

It’s no surprise, then, that the Japanese are delving further into the feetfirst arena. If Honda’s Helix proves successful and a larger, less scooterlike model evolves, perhaps the dream that started almost 80 years ago will come to reality. If that happens, the feet-first motorcycle will finally be given the legitimacy that many people feel it already deserves.®

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

December 1986 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1986 -

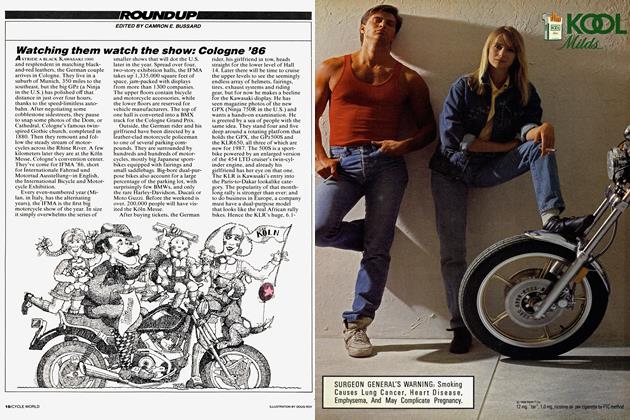

Roundup

RoundupWatching Them Watch the Show: Cologne '86

December 1986 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

December 1986 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

December 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

1987 Previews And Riding Impressions

1987 Previews And Riding Impressions1987 New Model Preview

December 1986