IN THE BEGINNING

The First Motorcycle Was Built 100 Years Ago-Here’s How It All Began

BILL STERMER

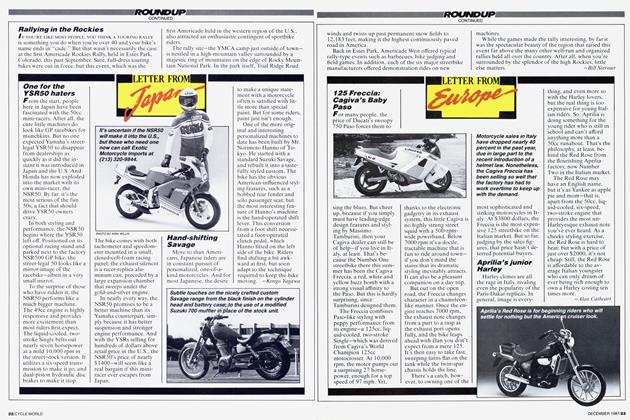

INVENTION RARELY RESULTS from a single stroke of genius. More often than not, it stems from a fortunate combination of related events occurring in just the right sequence. And so it was with a memorable occasion that is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year: the invention of the motorcycle by Gottlieb Daimler.

Understand, of course, that the world was quite a different place back in l 885. The Civil War had been over for 20 years, Grover Cleveland was president, and the world was in the midst of an age of steam propulsion that was revolutionizing mass transportation. Huge steamships regularly plied the Atlantic, and steam locomotives linked towns and villages both here and in Great Britain. But although Nicolaus Otto and Eugen Langen had patented the four-stroke principle of internal combustion in Germany nine years earlier, individual transportation was still by the age-old means of muscle power.

Actually, the very first twowheeled vehicle was a device called the hobbyhorse, which had been invented almost 70 years earlier, in l 8 l 6. but it wasn’t self-propelled. It consisted of a wooden frame and saddle, and the rider straddled it and merely pushed with his feet. In l 835, an Englishman fit pedals to the front wheel of a hobby horse and started a fad. These vehicles, with their ironrimmed wheels, came to be known as “boneshakers.” They gradually were equipped with larger and larger front wheels, eventually evolving into the five-foot-high “Penny-Farthing.” It wasn’t until 1885 that the first “safety bicycle,” with equally sized wheels and rear chain drive, appeared on the scene.

But surprisingly, the first motorcycle borrowed little from bicycle technology; what’s more, its four-stroke engine was to be pivotal in the evolution of the automobile, just as the inventor of that first motorcycle, Gottlieb Daimler, was to become a pioneer in the automobile industry. Born in Schorndorf, Germany, in 1834. Daimler had worked as a carbine maker and a foreman of a locomotive company before taking up the designing of mills, tools and turbines. In 1863 he took over the management of the Bruderhaus in Reutlingen, a socialistic workhouse for orphans, where he befriended a 17front—or resigning.

He chose the latter.

In April of 1882, Daimler and Maybach entered into a partnership that made Maybach the engineer and designer in Daimler’s workshop in Cannstatt. There, they labored to develop a four-stroke engine that could be used to power a small, road-going vehicle. Their experiments were with tion involved a thin-walled, hollow tube inserted into the combustion chamber. Its other end protruded from the engine and was heated w hite-hot by the constant flame of a bunsen burner. Heat traveled by conduction to the open end inside the engine, where the hot tube ignited the fuel/air mixture.

Unfortunately, ignition timing was year-old mechanical genius named Wilhelm Maybach.

After Daimler had reorganized the Bruderhaus and placed it on sound financial footing, he went to work for the Deutz company. Nicolaus Otto had formed Deutz to manufacture his atmospheric gas engines, and he wanted Daimler to design an improved version. Daimler agreed, and brought along Maybach as his chief designer. But friction eventually developed between the old man Otto and the young Daimler; and in 1881. Daimler was given the option of either overseeing the new' Deutz engine branch in Russia—which effectively meant being banished to the eastern a 264cc, air-cooled, single-cylinder engine that, due to its absence of cooling fins, resembled a big, black pipe. Daimler and Maybach found that the engine ran best between 450 and 900 rpm. and it put out the grand total of one-half horsepower.

Daimler wanted to do away with the complex and unreliable slidevalve ignition system that had been used in most engines up to that time, but he also had a basic mistrust of electricitv. So after considerable test-

J

ing. he decided to adopt and improve upon the "bluherohezuendung,” or "hot-tube,” ignition that had been invented by Leo Funck of Aachen. True to its name, the hot-tube ignivirtually uncontrollable w ith the hottube system, and for a while Daimler regarded the project as hopeless. The biggest obstacle was premature ignition during starting, w hich would violently slam the piston in the opposite direction and cause the entire engine to jump—not to mention w hat it did to the person trying to start it..

Eventually. Daimler and Maybach overcame the starting problem. But before you rush out to enshrine these two as founders of our sport, you should first know that they had no intention of building a motorcycle per sc. Their decision to mount the engine on a two-wheeled testbed was hard and practical, and had nothing to do with wind in the face, bugs in the teeth, or any of the other kinesthetic stuff that makes motorcycles so addictive. Instead, they chose two wheels because their engine wasn’t powerful enough to drive a full-sized carriage—and because a two-wheeler was cheaper to build.

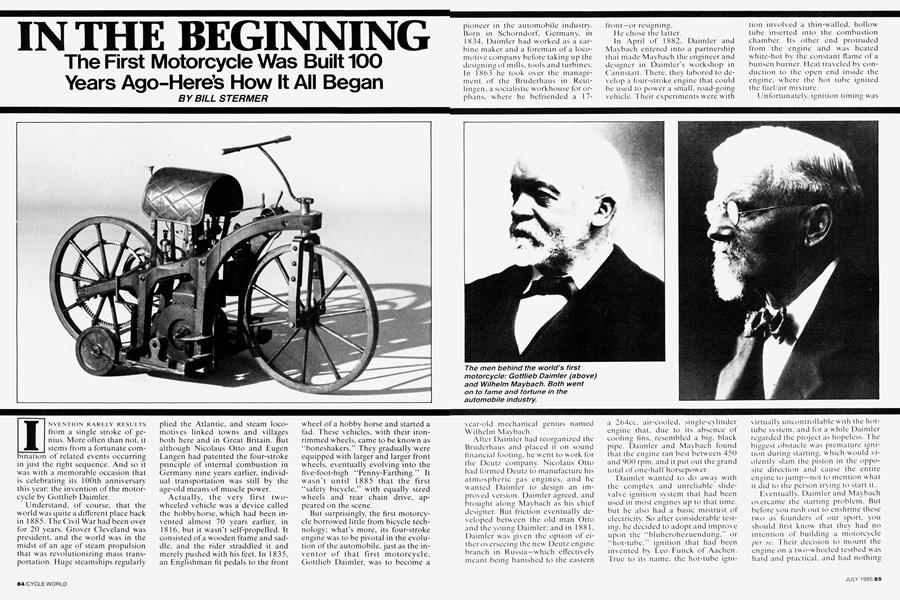

To carry the engine, Daimler and Maybach devised a cradle frame of wood and iron that more resembled the old hobby horse than any bicycle frame of that era. The engine protruded up beyond the frame, and was surmounted by a leather seat. Steering was by a tiller arrangement with a simple fork. Power was transmitted by belt from one flywheel pulley to a second, larger pulley whose internal gear engaged with a ring gear on the rear wheel. The wheels were woodenspoked affairs, and the “tires,” if that’s the word, were heavy, iron bands shrunk to fit, an arrangement that was common on horse-drawn wagons; Dunlop would not develop his first crude pneumatic tires for another three years. The contraption was so tall that the rider’s legs could not reach the ground, so it was fitted with a pair of outrigger wheels, not unlike bicycle training wheels.

Despite the fact it was the first true “motorcycle,’’ the “Einspur’’ (onetrack), as Daimler called it, incorporated many design features that were revolutionary for their day: a fancooled engine, an aluminum crankcase, and a float-type carburetor. In the years that followed, many other pioneers experimented with various engine locations, but the Einspur carried its engine right where it would remain for at least the first century.

And so on November IO, 1885, Daimler, Maybach and Daimler’s 17year-old son, Paul, wheeled the machine out of their Cannstatt shop, near Stuttgart, and fired it up. Young Paul climbed aboard and, by operating a lever, tightened the belt drive that set the machine in motion. By that act, he became the world’s first motorcyclist. Paul rode the machine from Cannstatt to the village of Unterturkheim, turned it around and rode back, a combined distance of 12 kilometers (about 7.5 miles).

Some sources state that on this first ride, the engine radiated so much heat that the leather seat caught fire. Other sources make no mention of this event. Some accounts state that Maybach also rode the Einspur on later occasions. And another charming bit of folklore claims that a short time after that first ride, Otto Zeis, Daimler’s nephew, secretly took the machine out by himself, T-boned a horse-drawn cab, and went flying over the horse. Zeis thus became the first person in history to become involved in an accident on a motorcycle—as well as the first to steal one. This story was, however, related by only one source, so its authenticity is somewhat questionable.

After this initial success with the Einspur, Daimler and Maybach pursued the development of an engine to power a four-wheeled carriage. They tested one that winter in a sleigh on a nearby frozen lake, but the results were unsatisfactory. So in 1886, Daimler purchased a horse-drawn carriage from the coachbuilders Wimpff and Son, strengthened the chassis, and fitted it with a 1.5-horsepower engine. From that point, Daimler and Maybach never looked back; the first motorcycle sat in a corner of the Daimler factory until it was destroyed by fire in 1 903. Today, two replicas of the original machine exist, one at the Daimler-Benz Museum in Stuttgart, West Germany, the other in the Indian Museum in Springfield, Massachusetts.

Though the Einspur did not produce any direct descendants, several other early engineers developed petrol-powered motorcycles soon after. British inventor Edward Butler had shown plans, in 1884, for a threewheeled “Velocycle” that was more motorcycle than car, but was unable to find financial backing for the project. He finally received the necessary funds and in 1 888 tested a prototype with rotary valves and a floatfeed carburetor.

Maybach went on to design a VTwin and a Four before Daimler’s death early in 1900. Soon thereafter, Maybach formed a partnership with Emil Jellinek to design an engine for a car that would bear the name Daimler-Mercedes. And Maybach also designed every early Mercedes-Benz auto, as well as several Zeppelin engines, before he died in 1929.

So circle November 10th on your calendar. And whereveryou might be that day, lift a glass to the memory of Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach, and to Paul Daimler, the world’s first motorcyclist.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialSoul-Searching In the Engine Bay

July 1985 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeThe Wrong Bag

July 1985 By Steve Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupMotorcycle Ergonomics: Trouble In the Fitting Room

July 1985 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupThe Ultra-High-Performance Yamaha Fz250 Phazer

July 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupThe Striking Yoshimura F1 And F3 Racers

July 1985