YAMAHA BW200

CYCLE WORLD TEST

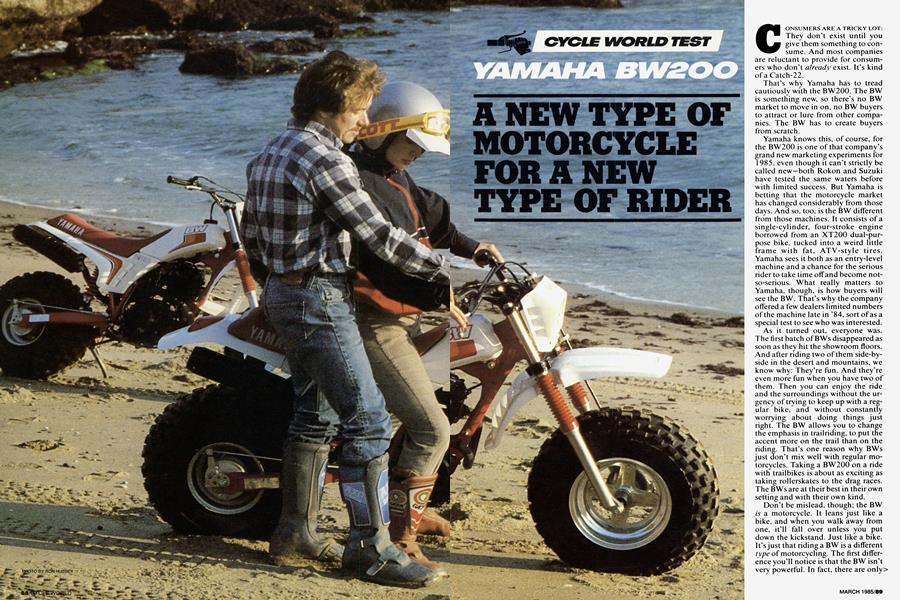

A NEW TYPE OF MOTORCYCLE FOR A NEW TYPE OF RIDER

CONSUMERS ARE A TRICKY LOT: They don’t exist until you give them something to consume. And most companies are reluctant to provide for consumers who don’t already exist. It’s kind of a Catch-22.

That’s why Yamaha has to tread cautiously with the BW200. The BW is something new, so there’s no BW market to move in on, no BW buyers to attract or lure from other companies. The BW has to create buyers from scratch.

Yamaha knows this, of course, for the BW200 is one of that company’s grand new marketing experiments for 1985, even though it can’t strictly be called new—both Rokon and Suzuki have tested the same waters before with limited success. But Yamaha is betting that the motorcycle market has changed considerably from those days. And so, too, is the BW different from those machines. It consists of a single-cylinder, four-stroke engine borrowed from an XT200 dual-purpose bike, tucked into a weird little frame with fat, ATV-style tires. Yamaha sees it both as an entry-level machine and a chance for the serious rider to take time off and become notso-serious. What really matters to Yamaha, though, is how buyers will see the BW. That’s why the company offered a few dealers limited numbers of the machine late in ’84, sort of as a special test to see who was interested.

As it turned out, everyone was. The first batch of BWs disappeared as soon as they hit the showroom floors. And after riding two of them side-byside in the desert and mountains, we know why: They’re fun. And they’re even more fun when you have two of them. Then you can enjoy the ride and the surroundings without the urgency of trying to keep up with a regular bike, and without constantly worrying about doing things just right. The BW allows you to change the emphasis in trailriding, to put the accent more on the trail than on the riding. That’s one reason why BWs just don’t mix well with regular motorcycles. Taking a BW200 on a ride with trailbikes is about as exciting as taking rollerskates to the drag races. The BWs are at their best in their own setting and with their own kind.

Don’t be mislead, though; the BW is a motorcycle. It leans just like a bike, and when you walk away from one, it’ll fall over unless you put down the kickstand. Just like a bike. It’s just that riding a BW is a different type of motorcycling. The first difference you’ll notice is that the BW isn’t very powerful. In fact, there are only two or three motorcycles made that are slower. But that’s okay, because the BW doesn't really need that much power. Having fun on the BW has little to do with going fast. Instead, the fun is in floating across the top of sand that would swallow a trailbike whole, and in cruising comfortably down a slippery hill that would send a skinny-tired bike sliding downward, out of control.

The fat tires do, of course, have some habits that will strike you as odd after you get off a regular bike. For one, they bounce. The big balloon tires offer about two or three inches of travel in addition to that provided by the mechanical suspension, but that travel is undamped. So hitting bumps at speed requires an exaggerated rearward stance to absorb the extra rebound. You’ll also notice that when you lean over to turn, the whole machine seems to move to the inside, simply because the tire contact patch is so wide.

Those aren’t necessarily negative observations, just observations. But some aspects of the wheel width are negative. For example, it takes considerable force to make the machine turn, because the wide front contact patch makes steering difficult, particularly at low speed. Yamaha has countered this by giving the bike a fairly wide handlebar so the rider has some leverage, but turning still requires quite a bit of muscle. And on off-cambers, the BW seems to like going downhill a little too much—it always strives to point itself that way, especially if the terrain is rocky. The tires simply cover so much area that it's difficult to miss rocks and bumps. Unless you hit the rock dead-center, it will cause the machine to tip one way or the other.

We did discover, however, that high tire-pressure helps the BW stay on course through the rocks and offcambers. High tire-pressure to a BW, incidentally, is anything over 5 psi. This makes the contact patches considerably narrower, and you can effectively miss the more undesirable elements on the trail. Low tire-pressure—anything less than five pounds—is best for smooth sandwashes and flat terrain.

Actually, with almost any amount of pressure in the tires, the BW handles sandwashes with ease. The front wheel seems never to wash out, no matter how far you lean. Sure, if you try to break the front end loose you can, but only if you have your weight way back and just turn the handlebar. Otherwise, the front wheel never suddenly lets go in the middle of a turn. Traction always is very predictable with the BW, and that means you can lean the bike over until your sleeves fill with dirt.

Of course, the primary market for the BW still is the entry-level buyer, and it’s not likely that he’ll care too much about the BW's ability to drag a handgrip through the sand. He’ll care more about how easy the machine is to ride in the first place. And the BW is very easy to ride. Its powerband couldn't be any smoother or more predictable, it shifts easily and smoothly, and the front and rear brakes are consistent, progressive and strong enough to haul the BW down from it's rather meager top speed. Most important of all, the machine has a low seat-height—a big plus on any beginner’s scorecard.

In several other ways, though, the BW can be misleading to the inexperienced rider. The fat tires make the machine look easier to ride than a comparably sized regular bike, but actually make little difference. On one hand, they give the machine a slight amount of stability on level ground, while on the other, the wheels make the machine feel wide and cumbersome. And the BW still has a manual clutch and a twist-grip throttle, two of the most difficult aspects of motorcycling for beginners to gain confidence with.

Beginners and long-time cyclists alike will be annoyed by several other of the BW’s faults. For one thing, it isn't always the easiest bike on Earth to start. If you open the throttle when you give it the first kick, you stand all too good a chance of flooding the engine, and it will be quite a few more kicks before the motor sputters back to life. And once you do get going, you'll have to stay fairly close to camp, because the 1.8-gallon fuel tank won’t let you go much farther than 45 miles if you ride at a quick pace.

You could say that nits like that don't mean much, because when a machine is in a class by itself, it naturally is the cream of the crop. And the Yamaha is, admittedly, a lot better than all of the other balloon-tired, 200cc two-wheelers on the market; there are none. But chances are that this Yamaha won’t be by itself for long. You can bet that, if the BW is half as successful as Yamaha’s early experiments show it can be, there soon will be a lot of other balloontired. 200cc two-wheelers appearing on and disappearing off showroom floors around the country.

In that respect, maybe the BW200 might just be a little too good, because Yamaha will soon have to move over and share the market and the consumers that the BW created. It’s kind of a Catch-22.

YAMAHA

BW200

List price $1299

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialA Matter of Opinion

March 1985 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1985 -

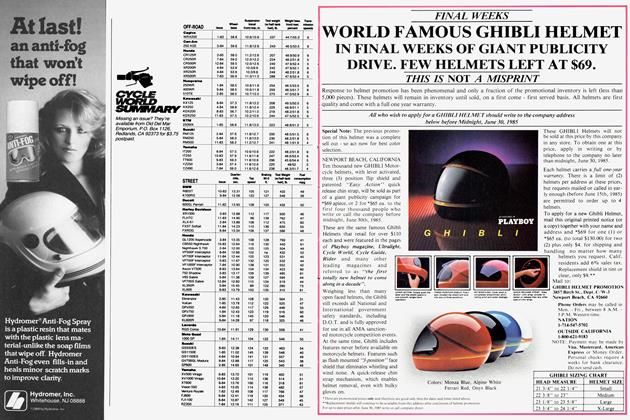

Departments

DepartmentsSummary

March 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupScooterwars: Honda And Yamaha Search For the New Front

March 1985 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupThe $590 Million Engine Rebuild

March 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThree-Wheeling, British-Style

March 1985