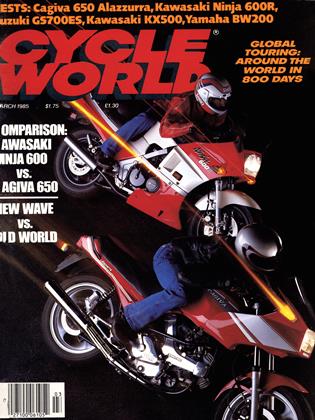

ENDURO DU SUPER MARE: BERSERK ON THE BEACH

And now, for something completely different....

MARK WILLIAMS

RICK KEMP

THE BRITISH DO THINGS DIFFERently. Very differently. And because their’s is a small island with a lot of easily irritated people aboard, nothing is done more differently than the running of an enduro. Instead of flailing across endless desert or mountain wastelands, the British run an enduro over what amounts to little more than an enlarged motocross course, lap after lap after lap. The resultant confusion is only mitigated by the relative ease with which the medics can get to the inevitable clumps of walking and rolling wounded.

However lackluster that concept might seem to the True Believers— those who yearn for wide-open spaces where men and machines can plummet into six-foot-deep bogs in complete solitude—it does not dull the spirit of such events. And it was in just that spirit that the Enduro du Super Mare was born.

The name was contrived to lend a certain continental flavor to a race held in a rather damp English seaside resort on a gloomy November weekend. This particular type of event is usually only done in France or Holland. Of course, the French have the good sense to do it on a warm summer’s day rather than in the cold November fog, but keep in mind that the British do things differently. And this

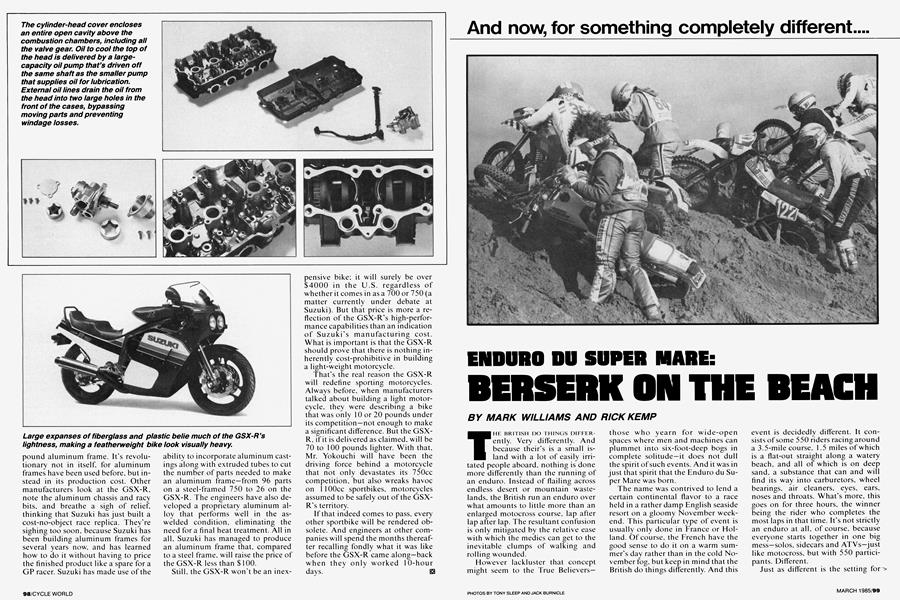

event is decidedly different. It consists of some 550 riders racing around a 3.5-mile course, 1.5 miles of which is a flat-out straight along a watery beach, and all of which is on deep sand, a substance that can and will find its way into carburetors, wheel bearings, air cleaners, eyes, ears, noses and throats. What’s more, this goes on for three hours, the winner being the rider who completes the most laps in that time. It’s not strictly an enduro at all, of course, because everyone starts together in one big mess—solos, sidecars and ATVs—just like motocross, but with 550 participants. Different.

Just as different is the setting for the race. As holiday towns go, Weston Super Mare is predictably quaint. Battered by a hundred years of sun and sea spray, the Victorian architecture manages to present a brave facade against the mournful gray fall skies. Stuck away in a rather unfashionable corner of southwest England, Weston understandably courts anyone who throws commerce its way. Welcoming hordes of braying twowheelers, however, flies in the face of the prevailing civic wisdom, for despite the slowly declining tourist trade, other British seaside communities shun motorcyclists and the like. But the Enduro du Super Mare brings money to the community, and no one knows that better than its 1984 organizers, Enduro Promotions, Ltd. This year they convinced the local officials to rope off the 2.5-mile beach so spectators could be charged one pound each to watch the fun and games. No one begrudged them this, even though with 550 fee-paying entrants (at about $ 18 each) and an estimated 60,000 spectators, the mathematics looked attractive.

This year the promoters strung out what previously was a one-day event into a long weekend, with Saturday consisting mostly of organizational matters and sideshows. There was, for example, an arena trials starring no one you ever heard of, followed by—honest—an ATC race for paraplegics.

These activities passed almost unnoticed due to the fact that most people were involved in a mass deceit commonly known as “scrutineering,” a lengthy business that involved most of each rider's pit crew standing around with armfuls of steel wool while their machinery repeatedly failed the sound check. The Enduro du Super Mare wasn’t sanctioned by any official motorsports body whatsoever, so riders weren’t obliged to fit lights or enduro-legal tires to the out-and-out motocrossers that made up most of the field, and were required only to pass a sound test. You could always spot the riders who forgot to remove the added packing from the silencer’s entrails; their bikes wouldn’t pull second gear.

Once the anxiety of scrutineering was over and everyone had made at least rudimentary efforts to waterproof their bikes, the gladiators went off in search of Weston’s night life. The entry fee had included a free ticket to a local disco, and the two different colors that these tickets came in didn’t seem significant at first. Much, much later, however, it frequently became necessary for one disco’s owner to try to convince a group of inebriated motocrossers that each of the two colors was for a different disco, and that they were trying to gain access to the wrong one. And while some riders did actually go to bed before midnight, the purity of their slumber was constantly interrupted by the unofficial wheelie contest going on along the promenade.

As with so many fun events, come raceday and the promise of good weather, things took a turn for the serious with all the top riders starting their psych-out sessions an hour or so before the noon start. Though many of the names are unfamiliar to Americans, most of Britain’s MX superheros were in the assemblageriders like Graham Noyce, Jem Whatley, Neil Hudson and Derrick Edmondson. Kawasaki had two of its top Euro riders, Laurence Spence and Andy Nicholls, in tow, plus a bunch of works mechanics over from Holland just in case anyone needed a crank regrind. But the field nonetheless was filled mostly by riders who were unknown even locally and were just in search of a good time. Some were even nursing hangovers from the previous night. “This event’s daft enough,” muttered one rider, “that I might as well ride it drunk.”

At the appointed hour, the bikes were supposed to leave the pare ferme for the beach, but sloppy crowd control—or rather a total lack of crowd control—meant that they were half an hour late at the start. Eventually, however, the starter’s gun was fired, and 550 assorted machines exploded into life and tore off along the beach straight. Waiting for them at the other end was a formidable hill, which caused a formidable traffic jam. The race ended right there for a few, and for the others who continued, the event lying ahead was to be, well, just different.

The whole problem with riding sand hills is that too much wheelspin instantly digs an axle-deep hole, and the only solution is to drag the bike out of it, turn around, go back down and start again. The difference between normal riders and the abnormally fast ones is that the fast ones skirt the traffic jams without backing off—even on hills that are wall-towall with expired sidecar outfits. On the big uphills, there were just as many bikes going down as there were going up, and an even greater number going no place at all.

After the first few laps it was obvious that the funnel going into the lapscoring area would be permanently choked with traffic in trouble. It was not a typical race scene—scores of riders stationary, gagging from the oily smoke and standing in water-logged sand. Some found it so repulsive that they actually forwent a scored lap rather than stand in line amongst the carnage. But not the fast boys; they found lines around and over the mayhem, lest a lap of labor be lost.

Ten laps into the race, some sort of order started to emerge from the chaos. Jem Whately was flying up front, followed closely by local boy Chris Bowd on a Honda 500. A lap behind them came Derrick Edmondson, Geoff Mayes, Vic Allan, Geraint Jones, Colin Luce, Neil Hudson and Graham Noyce.

At this stage, the scene in the pit area was only marginally less frantic than that on the racetrack. The routes through the pits were disorganized and chaotic, so many of the riders just couldn’t find their pit crews. This led to many confused and frenzied persons borrowing fuel, goggles and anything else they could lay their gloves on, which, in turn, obliged crews to rush about furiously replenishing stocks. Many riders who did, in fact, manage to locate their pits found the sites empty.

Again, though, the leaders somehow managed to float above the problems that plagued the majority of riders. After about an hour and a half, the leaders had completed 12 to 1 5 laps, and most had developed a preferred style for negotiating the long straight, which had become the most crucial part of the course. Lessaccomplished riders used the straight to recover their wind after the rigors of mountainous sand dunes and brine-filled gullies, but the fast boys used it to go even faster. Sand roost was the main problem here, and avoiding it wasn’t easy. Riding faceto-the-tank was almost lethal, so it was best to sit way back and tuck in behind the front numberplate.

Considering that some of the works bikes probably hit 90 to 100 mph at the end of the straight, it was no surprise that many of the two-strokes either seized or boiled their radiators dry. Many used oversize main jets or merely whacked on a bit of choke to overcome this malady, but inevitably, the big four-strokes were quicker at straight's end. There was to have been a cash prize for the fastest speed along the straight, but that was aborted when the organizers couldn't get the radar gun to work.

continued on page 106

continued from page 102

With one hour to go, the leader board began to change. Noyce came up to engage Whately in a crowdpleasing duel, but then Whately’s Kawasaki fell victim to the long straight, and he was forced to retire with a seizure. By this time, most of the course-marker ropes had been knocked down, and accusations were flying about the legitimacy of some riders' lines. The pit action was. however, a little more orderly by then, and you could feel the tension rising as crews blurred into action to get their men back out onto the circuit. One of Noyce’s fuel stops was timed at seven seconds, but, to his dismay, his Husqvarna didn't work with an equal level of efficiency, and he was soon out with a cracked radiator.

As is the nature of these things, it was still far from clear who’d won the Enduro du Super Mare until eight hours after the checkered flag had dropped. The promoters had, they thought, been clever by installing a computer to avert the chaos of the previous year’s results checking. Unfortunately, there were just a few teensy-weensy gremlins in the software, which put an ATV 10 laps ahead of the first solo. In a triumph of old technology over new, the count was eventually done manually, giving the laurels to Roger Harvey (31 laps), who was followed by Neil Hudson (30 laps).

Harvey’s prizes included a holiday for two at a yet-to-be-named destination—probably Weston Super Mare— and awards were given to anyone who managed more than 24 laps. Twenty-eight of the 345 finishers traipsed wearily homeward bearing this particular honor; the rest averaged about 14.7 laps. You can be sure, though, that each of those finishers did things in his own way, just a little differently from the rest.

That's British tradition.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialA Matter of Opinion

March 1985 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1985 -

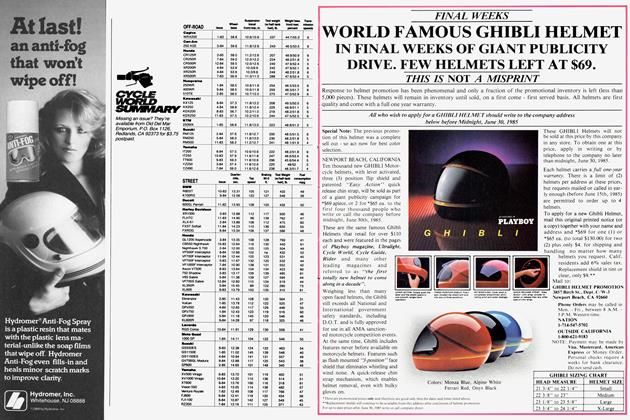

Departments

DepartmentsSummary

March 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupScooterwars: Honda And Yamaha Search For the New Front

March 1985 By David Edwards -

Roundup

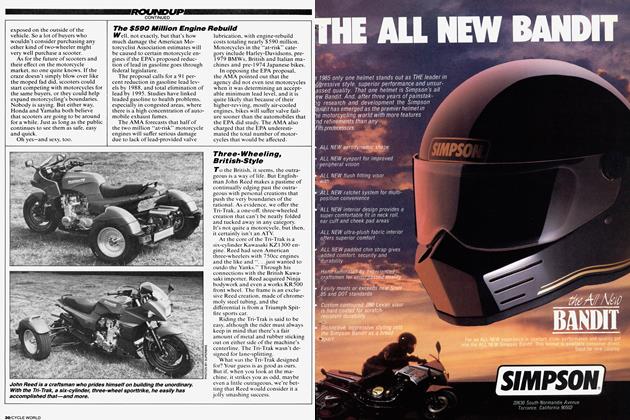

RoundupThe $590 Million Engine Rebuild

March 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThree-Wheeling, British-Style

March 1985