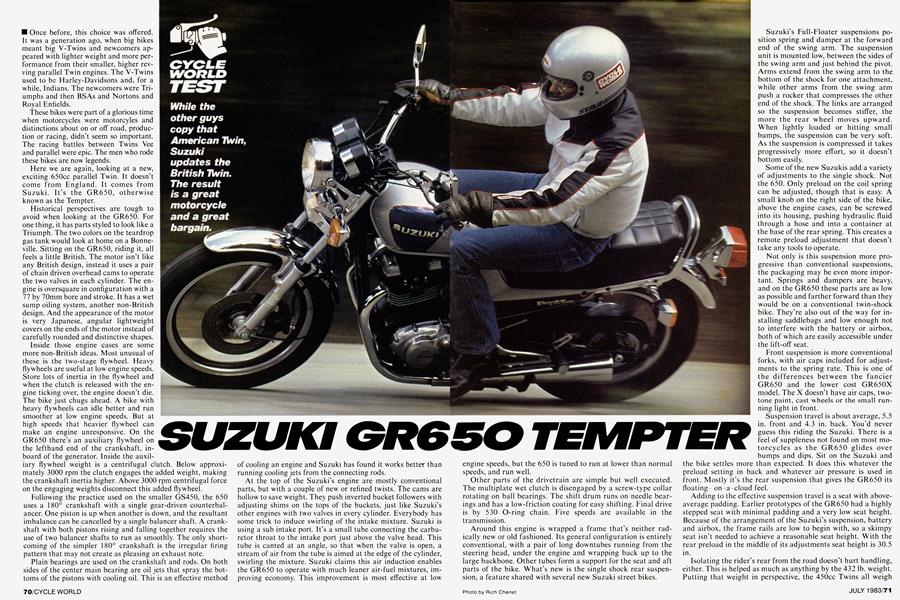

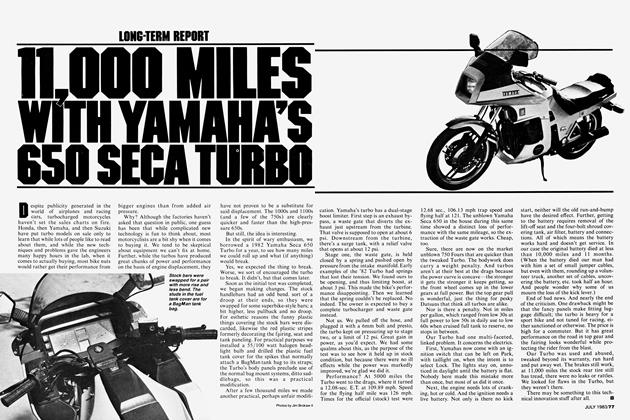

SUZUKI GR650 TEMPTER

CYCLE WORLD TEST

While the other guys copy that American Twin, Suzuki updates the British Twin. The result is a great motorcycle and a great bargain.

Once before, this choice was offered. It was a generation ago, when big bikes meant big V-Twins and newcomers appeared with lighter weight and more performance from their smaller, higher revving parallel Twin engines. The V-Twins used to be Harley-Davidsons and, for a while, Indians. The newcomers were Triumphs and then BSAs and Nortons and Royal Enfields.

These bikes were part of a glorious time when motorcycles were motorcyles and distinctions about on or off road, production or racing, didn’t seem so important.

The racing battles between Twins Vee and parallel were epic. The men who rode these bikes are now legends.

Here we are again, looking at a new, exciting 650cc parallel Twin. It doesn’t come from England. It comes from Suzuki. It’s the GR650, otherwise known as the Tempter.

Historical perspectives are tough to avoid when looking at the GR650. For one thing, it has parts styled to look like a Triumph. The two colors on the teardrop gas tank would look at home on a Bonneville. Sitting on the GR650, riding it, all feels a little British. The motor isn’t like any British design, instead it uses a pair of chain driven overhead cams to operate the two valves in each cylinder. The engine is oversquare in configuration with a 77 by 70mm bore and stroke. It has a wet sump oiling system, another non-British design. And the appearance of the motor is very Japanese, angular lightweight covers on the ends of the motor instead of carefully rounded and distinctive shapes.

Inside those engine cases are some more non-British ideas. Most unusual of these is the two-stage flywheel. Heavy flywheels are useful at low engine speeds.

Store lots of inertia in the flywheel and when the clutch is released with the engine ticking over, the engine doesn’t die.

The bike just chugs ahead. A bike with heavy flywheels can idle better and run smoother at low engine speeds. But at high speeds that heavier flywheel can make an engine unresponsive. On the GR650 there’s an auxiliary flywheel on the lefthand end of the crankshaft, inboard of the generator. Inside the auxiliary flywheel weight is a centrifugal clutch. Below approximately 3000 rpm the clutch engages the added weight, making the crankshaft inertia higher. Above 3000 rpm centrifugal force on the engaging weights disconnect this added flywheel.

Following the practice used on the smaller GS450, the 650 uses a 180° crankshaft with a single gear-driven counterbalancer. One piston is up when another is down, and the resultant imbalance can be cancelled by a single balancer shaft. A crankshaft with both pistons rising and falling together requires the use of two balancer shafts to run as smoothly. The only shortcoming of the simpler 180° crankshaft is the irregular firing pattern that may not create as pleasing an exhaust note.

Plain bearings are used on the crankshaft and rods. On both sides of the center main bearing are oil jets that spray the bottoms of the pistons with cooling oil. This is an effective method of cooling an engine and Suzuki has found it works better than running cooling jets from the connecting rods.

At the top of the Suzuki’s engine are mostly conventional parts, but with a couple of new or refined twists. The cams are hollow to save weight. They push inverted bucket followers with adjusting shims on the tops of the buckets, just like Suzuki’s other engines with two valves in every cylinder. Everybody has some trick to induce swirling of the intake mixture. Suzuki is using a sub intake port. It’s a small tube connecting the carburetor throat to the intake port just above the valve head. This tube is canted at an angle, so that when the valve is open, a stream of air from the tube is aimed at the edge of the cylinder, swirling the mixture. Suzuki claims this air induction enables the GR650 to operate with much leaner air-fuel mixtures, improving economy. This improvement is most effective at low engine speeds, but the 650 is tuned to run at lower than normal speeds, and run well.

Other parts of the drivetrain are simple but well executed. The multiplate wet clutch is disengaged by a screw-type collar rotating on ball bearings. The shift drum runs on needle bearings and has a low-friction coating for easy shifting. Final drive is by 530 O-ring chain. Five speeds are available in the transmission.

Around this engine is wrapped a frame that’s neither radically new or old fashioned. Its general configuration is entirely conventional, with a pair of long downtubes running from the steering head, under the engine and wrapping back up to the large backbone. Other tubes form a support for the seat and aft parts of the bike. What’s new is the single shock rear suspension, a feature shared with several new Suzuki street bikes.

Suzuki’s Full-Floater suspensions position spring and damper at the forward end of the swing arm. The suspension unit is mounted low, between the sides of the swing arm and just behind the pivot. Arms extend from the swing arm to the bottom of the shock for one attachment, while other arms from the swing arm push a rocker that compresses the other end of the shock. The links are arranged so the suspension becomes stiffer, the more the rear wheel moves upward. When lightly loaded or hitting small bumps, the suspension can be very soft. As the suspension is compressed it takes progressively more effort, so it doesn’t bottom easily.

Some of the new Suzukis add a variety of adjustments to the single shock. Not the 650. Only preload on the coil spring can be adjusted, though that is easy. A small knob on the right side of the bike, above the engine cases, can be screwed into its housing, pushing hydraulic fluid through a hose and into a container at the base of the rear spring. This creates a remote preload adjustment that doesn’t take any tools to operate.

Not only is this suspension more progressive than conventional suspensions, the packaging may be even more important. Springs and dampers are heavy, and on the GR650 these parts are as low as possible and farther forward than they would be on a conventional twin-shock bike. They’re also out of the way for installing saddlebags and low enough not to interfere with the battery or airbox, both of which are easily accessible under the lift-off seat.

Front suspension is more conventional forks, with air caps included for adjustments to the spring rate. This is one of the differences between the fancier GR650 and the lower cost GR650X model. The X doesn’t have air caps, twotone paint, cast wheels or the small running light in front.

Suspension travel is about average, 5.5 in. front and 4.3 in. back. You'd never guess this riding the Suzuki. There is a feel of suppleness not found on most motorcycles as the GR650 glides over bumps and dips. Sit on the Suzuki and the bike settles more than expected. It does this whatever the preload setting in back and whatever air pressure is used in front. Mostly it’s the rear suspension that gives the GR650 its floatingon-a-cloud feel.

Adding to the effective suspension travel is a seat with aboveaverage padding. Earlier prototypes of the GR650 had a highly stepped seat with minimal padding and a very low seat height. Because of the arrangement of the Suzuki’s suspension, battery and airbox, the frame rails are low to begin with, so a skimpy seat isn’t needed to achieve a reasonable seat height. With the rear preload in the middle of its adjustments seat height is 30.5 in.

Isolating the rider’s rear from the road doesn’t hurt handling, either. This is helped as much as anything by the 432 lb. weight. Putting that weight in perspective, the 450cc Twins all weigh around 400 lb. A Triumph Bonneville with electric start weighs 444 lb. and a BMW R65 weighs 438 lb. Yamaha’s Seca 550 weighs 424 lb. and the XS650 weighs 474 lb. This puts the GR650 on the lighter side of medium-weight, not really as light as the 450 class Twins, but significantly lighter than motorcycles of similar engine size.

What this means to the GR650 rider is less mass to throw around. Chassis geometry is about as average as possible; rake 27.5°, trail 4.4 in. Nothing surprising here. But bigger, heavier motorcycles with these figures aren’t as tossable as the 650 Suzuki. Particularly at low speeds the Suzuki is an easy handling bike. It invites riding on bad roads where a rider needs to steer at the last minute around obstacles or holes.

The rest of the bike is happiest on back roads, too. The single front disc and rear drum brakes are better than Suzuki’s fancier triple disc systems with antidrive. Because of difficulty bleeding the anti-dive systems on more expensive Suzukis, they lose brake feel; the 650 doesn’t.

Engine characteristics, and more important the gearing, also fit the lowspeed nature of the 650. More than most any other mid-size Japanese Twin, the GR650 is tuned to provide lots of low and mid-range power. The swirl-inducing air jets, the carefully tapered and small intake ports and cam timing all make for an excellent, broad powerband.

What it doesn’t make is peak power.

Up to 60 mph the 650 Suzuki is a joy to ride. At low speeds the engine is smooth and there are no gaps in the powerband. It pulls from idle, the twostage flywheel doing its job without intruding. Below 3000 rpm it pulls like a tractor and it’s amazingly resistant to stalling when the clutch is let out too quickly. Above that the engine is somewhat more responsive, but there is no real transition. You don’t feel the flywheel disengage or engage. The clutch is magnificent. Start the Suzuki cold, put it in gear and you don’t hear a sound or feel a tug. It releases fully. It never gets grabby hot or cold. This can’t be said for the clutches on some of Suzuki’s other mid-size bikes. Add shifting that’s light and responsive and it makes exercising the 650’s engine a pleasure.

Only the growing level of vibration above 60 mph intrudes on the fun. Even with the counterbalancer shaft, the engine feels busy around 5000 rpm, and with an engine speed of 4650 rpm at 60 mph that vibration period comes at common highway speeds. Above 70 mph things settle down a little, but the real sweet spot is just at or below 60 mph. Up to that speed it maintains that delightful Big Twin feel, chugging the bike forward with authority.

As mid-size Twins go, this gearing is lower than normal. A BMW 650 runs along happily at 3900 rpm at 60 mph, while a Yamaha 650 is spinning 4200. Even Honda’s high-revving 650 Four only turns 4000 rpm at 60. It’s a shame the Suzuki is geared so low, because it has an engine that could pull much higher gearing. Raising the final drive gearing with a bigger front sprocket will be the easiest cure, but the gearing in 1st is about right with the current final drive. Ideally the GR650 would have another gear, higher than the current 5th. It could certainly pull it.

What the GR650 rider gets from this gearing is spectacular top gear lunge. Big Twins are famous for lots of low-speed torque, but most are geared to take advantage of it, and their resulting top-gear roll-on performance is not great. This bike has great roll-on performance. From 40 to 60 mph only takes 4.3 sec. and from 60 to 80 mph takes 5.6 sec. These figures are far better than comparable sized motorcycles. Peak performance is not so great. Because the Suzuki is tuned for so much output at lower rpm, peak power is not as high as it could be. A Honda 650 Twin is much quicker in quarter-mile acceleration, though the Suzuki is a match for a BMW or Yamaha.

Where the low gearing hurts is in the gas tank. To start with, it’s a little small at 3.4 gal. Then add 45 mpg in hard riding and the range is only so-so. Ridden more gently on the Cycle World mileage loop, the GR returned 57 mpg. If the GR were geared to take advantage of its good power at low engine speeds it could provide excellent gas mileage. As it is, the mileage is only average.

Comfort drew mixed reviews. Nothing wrong with the suspension or controls, but one of the riders would have preferred a bit less of a step in the seat and less height, pullback and bend in the bars, while wishing that the pegs were lower. One virtue of a Twin is narrowness and that should bring with it better cornering clearance and that should let the pegs be closer to the

ground. The low seat amplifies the bend of the leg and straight-arm riders found themselves wedged against the step. Suzuki has thoughtfully provided conventional bars, easily swapped for a lower, shorter pair and if that doesn’t work the seat could have maybe an inch more padding in the middle, an inch shaved off the back. And most of the crew liked it fine the way it was. Matter of personal preference or old war wounds.

Riding the Suzuki 650 is in most other ways satisfying. It doesn’t have many annoying features, those little quirks that make some bikes frustrating to ride. It starts easily with the push of a button and handles predictably on all kinds of surfaces.

Servicing is another mixed bag. There are only two spark plugs to change, and they’re out in the open, but the shim-type valve adjustment can be a nuisance. There is no cam chain adjustment or ignition adjustment. Access to the battery and air filter is good, but the battery has to be pulled to check the water level, not so good. At last Suzuki is installing shorter mufflers on its street bikes so the exhaust system doesn’t have to be moved to pull the rear axle for tire changes. That same exhaust system is quiet, only emitting a strangled little throb of muted power. Mechanical noise from the GR is low enough it should be able to make a little more pleasant sound than it does.

Add to this, a collection of convenience features. Under the lift-off seat is a chain, opened with a magnetic key ring provided with the bike. It’s too short to be of most use, but it can make the security-conscious rider happy. Instruments include an almost accurate gas gauge and a digital gear position indicator. There is a minimum of tacky trim, excepting the little rubber pad on the handlebars and the front running light encased in genuine chrome-plated plastic. Not bad, though.

One feature stands out as an overriding reason to buy the GR650. Price. List on the standard GR650 is $2399. The lower cost GR650X has a list price of $2149. That, friends, is cheap. This is a blue-light-special on two wheels. It’s the equivalent of the 19-cent hamburger, the $29.95 paint job and free kittens rolled into one. For a little over two grand you can own a real, honest-to-gosh, full-size, brandnew, undented motorcycle.

There are only two things we’d want to see changed. First, raise the top gear ratio. Second, change the name. You’ll notice we've carefully been referring to this as the GR650, a perfectly good name for this great bike. On the sidecovers there’s another name. Tempter. Come on, Suzuki. Tempter is a silly name. This is not a silly motorcycle.

It's an excellent motorcycle. It’s worth every penny. It’s a fitting successor to all those 650 Twins of a generation ago.

It even burned out its headlight, just like those big Twins of so long ago. Think of it as character. SI

SUZUKI

GR650 TEMPTER

$2399