The Hossack Front Suspension

An Alternative to Telescoping Forks Could Be Lighter, Stronger and Better. But Does Anybody Want It?

Miles McCallum

Quick, think of a motorcycle. Any motorcycle: Size or type doesn’t matter. Have it pictured in your mind? Focus on the front end. We’ll bet the front wheel is held to the frame by a set of shiny telescopic forks.

Telescopic forks are so universal these days it’d be surprising if your motorcycle image didn’t use a set. But if we had asked the same question 25 years ago, the picture might have been a little different. Telescopic forks were being used on more and more machines of that day, but they were by no means the only front suspension. Leading link forks were used on off-road bikes and BMWs for the smoother ride they provided, and on many less expensive machines because they were cheaper than telescopies. The superb handling Moto Guzzi GP road racers all used the leading link design. Girder forks were still seen occasionally, but like the leading link, they would soon be replaced by telescopies.

The switch to telescopic front suspension was a change to a system with superior performance, and it didn’t hurt that it looked tidier as well. Hydraulically damped telescopies were first seen in the

late 1930s, and by 1950 were becoming the road racing standard. They could offer more, and better damped, suspension travel than the girder forks they replaced on many machines. They were also stiffer than most of the leading link designs, and handling improved with the telescopic substitution.

Street machines followed the racers, and by the early 1960s telescopic forks were used on the majority of street bikes. There were a few holdouts, such as the Honda Dreams and the BMWs with their leading links, but they were gone by 1970. The last mass produced motorcycle to use a non-telescopic front suspension is the Honda C70. Telescopic forks are so standard now it’s hard to picture a motorcycle without them, and improvements to front suspension mean better telescopic forks. Motorcycle manufacturers experiment with alternatives only in the furthest corners of their test tracks, and all that is ever seen in public is the work of basement tinkerers and tuner-designers who are never happy simply having a system that works as well as everyone else’s.

Which brings us to Norman Hossack and the Hossack front suspension. Norman Hossack is a 37-year-old automotive engineer who settled in London after moving from what he describes as a technical wilderness in his native Rhodesia. He worked as a mechanic and fabricator for the McLaren Formula One racing team, and had a hand in Emerson Fittipaldi’s world championship winning car and the McLaren Indianapolis winner of 1973. He also raced motorcycles: a Seeley-framed Yamaha Twin to be exact. The bike never lived up to his expectations, and eventually a serious crash put him in the hospital. From his hospital bed he renounced motorcycles, disillusioned with the current state of the chassis art. As so often happens, his interest in motorcycles returned, and with it in 1979 the realization that the answer to his chassis complaints had been there all the time. Almost all race cars use a double A-arm front suspension because it is simple, light, strong, and can be tuned to offer almost any camber versus wheel deflection curve desired. Turn it around, reasoned Hossack, put it on the front of a motorcycle chassis, and it would still be simple, light and strong. In addition, it would allow tuning steering geometry versus wheel travel and could provide any amount of anti-dive or pro-dive braking effect desired. In sum it would answer the complaints that critics of telescopic forks had leveled at them over the years.

How does this wondrous device work? Take a look at Fig. 1, and try to ignore the initial impression that it consists of a million bits and pieces. It’s simpler than it looks. The frame terminates in a large box section containing four needle roller bearing housings, one in each corner. Two A-arms pivot from there, lying roughly parallel to the ground. Suspension is provided by a single shock absorber actuated by a cantilever off the bottom wishbone, much like an early Yamaha monoshock rotated half a turn. The front fork, or upright as Hossack prefers to call it, hinges from the front of the A-arms via two ball joints. Steering is accomplished by rotating the entire upright, and since it moves up and down with the wheel travel, this is slightly more complicated than with conventional telescopic forks. Because the handlebars can’t be mounted directly to the upright, they pivot on a boss tied to the frame. Two rods, with ball jointed ends, come off the handlebars to meet in a V. Then two more rods, again with ball jointed ends, come off the upright to form another V sharing its apex with the first V. This arrangement allows the bars to steer the upright without interfering with its up and down movement.

The Hossack front suspension has the potential to eliminate the suspension problems associated with telescopic forks. Because of their inclination, telescopic forks actually have pro-dive tendencies during braking, with part of the braking load transmitted to the chassis by the fork springs. This causes the front of the bike to compress further than would be expected by weight transfer effects alone. As telescopic forks compress, the wheelbase is shortened and steering rake reduced. The Hossack system, in contrast, can be configured to give neutral or anti-dive characteristics on braking, and maintain the wheelbase and steering geometry as normal weight transfer compresses the front suspension to the desired degree.

Although friction has been substantially reduced in telescopic forks by the use of Teflon and other low-friction bushings, they’re still fairly sticky when compared to the swing arm rear suspension. The Hossack front end has the potential to be as friction-free as a swing arm. And like the rear suspension, it can use a single standard shock absorber. Damping mechanisms in telescopic forks are still primitive when compared to motocross quality shock absorbers, so the combination of less friction and improved damping should lead to better front wheel control.

When telescopic forks were replacing leading link designs, they offered the advantage of reduced steering inertia. Leading link forks had large masses of metal considerably offset from the steering axis, while the telescopic forks were positioned closer to it. The people who now do computer models of motorcycle dynamics tell us that reduced steering inertia is a good thing, often eliminating wobble problems. Certainly some of the leading link machines handled better with telescopic forks. The Hossack suspension reduces steering inertia even further by only having the upright turn; the spring and damper don’t need to turn with the wheel. The reduced inertia should offer a handling improvement.

The final advantage a motorcycle designed to use the Hossack front end should have over a conventional bike is more chassis stiffness for a given weight, or less weight for a given stiffness. For years critics of motorcycle design have complained that conventional front suspensions overload the steering head area of the frame. Loads that are generated at ground level are given a 3 ft. lever in the front forks to twist the frame around. So the frame has to be heavy. The forks themselves are subjected to heavy bending loads and, because they have to be round to telescope, are far from the ideal shape to resist those loads. So the forks have to be heavy. The Flossack eliminates many of these complaints. Instead of concentrating bending loads from bumps and braking into two steering head bearings 5 or 6 in. apart, they are distributed into the frame by the four more widely spaced A-arm mounts. The A-arms themselves are triangulated and immensely strong. The bottom A-arm can attach to the upright immediately above the tire, giving the A-arms more leverage on the upright for a given motorcycle height. And the upright itself can be much stiffer than a pair of fork tubes of the same weight.

The biggest advantage the Hossack suspension has, though, isn’t one of these theoretical considerations. It’s the fact that Norman Hossack has built a racing motorcycle around his ideas, and it’s out leading races. His bike uses a mildly tuned Honda XL500 engine, and races in the four-stroke Single class in England.

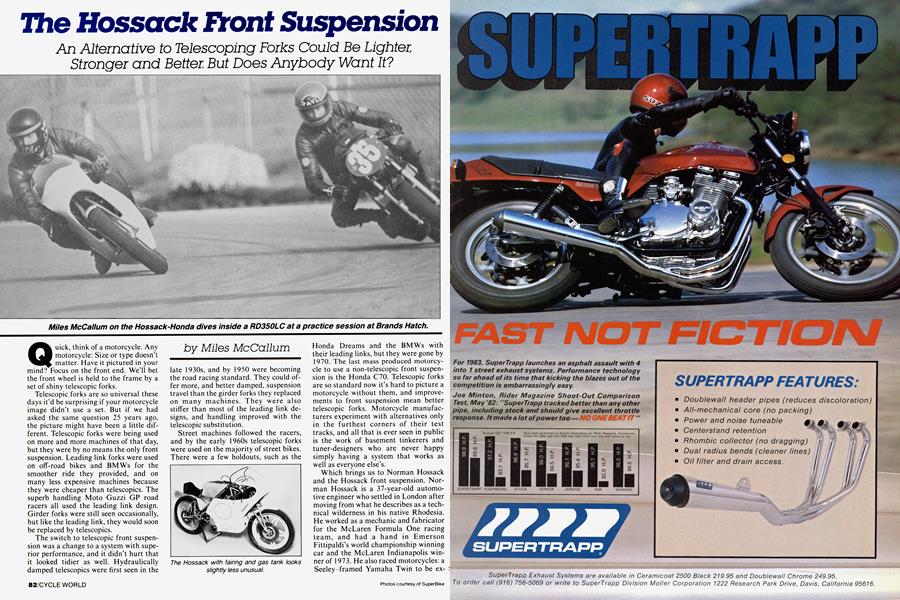

The frame is a collection of straight tubes, and adds an unusually short swing arm to the double A-arm front suspension. The package is very light at 215 lb. wet, ready to race. The machine currently holds lap records for its class at Brands Hatch and Snetterton; Brands is a rider’s circuit, where handling and brakes count more than horsepower. Snetterton is a speed circuit. The Hossack has lapped there at 1 min. 17.3 sec., faster than any unlimited displacement production bike. The Hossack has also raced in 500 and open GP classes, and has finished in the top three against the likes of TZ350s.

A trip to Brands Hatch was arranged to try out Norman’s XL500 powered racer and see if it lived up to its promise. The bike is very light, though very little consideration was given to save weight: the chassis components are designed to handle far more stress than the Honda could ever give. About 40 laps of the short circuit were done in all, and, although I didn’t attempt to push it to its absolute limit, it was very impressive to ride. The stable cornering speed is the same as a conventional motorcycle—the improvement comes with higher entry speeds, and much better braking and control. Initially, braking feels strange, due to the lack of front end dive, but the extent to which you can hold the front brake on while leaning over a long way, and still be able to change line is stunning. Even overdoing things, and locking the front wheel, produced some surprises: release the brake, and the bike sorted itself out with no more than a twitch and the nasty memory that you almost collected more gravel rash. I want one!

Is the Hossack front suspension an innovation that will see wider use, or is it just one of those interesting devices that turn up occasionally at club level road races for a season or two, never to be seen again? We suspect it will turn up again on other road racers; it certainly seems to offer some advantages. Noted frame builder Rob North was asked about the Hossack and is very excited with the possibilities.

However, the Hossack front end may have a few problems of its own. The Hossack-Honda uses only about 3 in. of suspension travel, and there may be problems with bump steer with the current steering mechanism if travel is increased and more steering lock is used. Both of these changes would have to be made for off -road or street Hossack suspensions. And even if the Hossack front end turns out to be trouble-free, and delivers on all its performance promises, it would still have one last, high hurdle before it would be used on street bikes: will any manufacturer build a bike that strays so far from that mental image of a motorcycle with shiny fork tubes?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

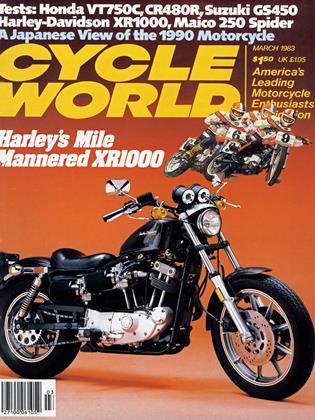

Up Front

Up FrontFor Adults Only

March 1983 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1983 -

Book Review

Book ReviewVincent Vee Twins

March 1983 By AG -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

March 1983 By James F. Quinn -

Features

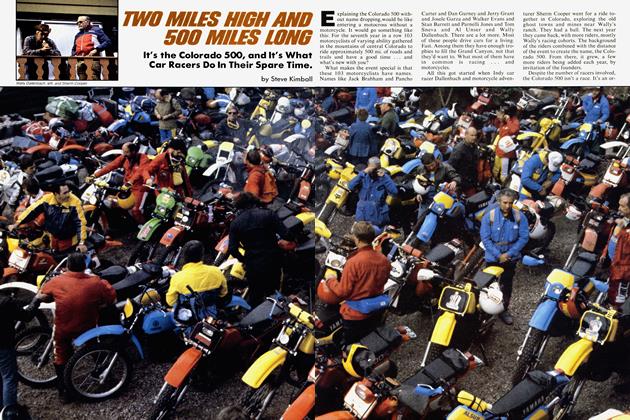

FeaturesTwo Miles High And 500 Miles Long

March 1983 By Steve Kimball -

Technical

TechnicalSouping the 650 Seca

March 1983 By John Ulrich