Handcrafted Thunder

The Harley According to Fondren.

Peter Egan

Everyone who really likes to ride motorcycles has probably considered building a personal bike from the ground up. A machine uncluttered by someone else’s notions of style, comfort and performance, and uncompromised by marketing committees who exist to offend the smallest number of people while stamping out the largest number of bikes.

For every hundred people who have this dream, of course, about eighty of us have a few extra thumbs and can’t be trusted with blunt scissors and brightly colored construction paper, much less a precision lathe and a bottle of Prussian blue. At least another dozen have the necessary skills but lack energy and persistence of vision. These are the people who advertise project bikes that are “98 percent complete.” That leaves another half dozen who work so slowly they turn senile and forget how to ride before the bike ever sees daylight, and maybe two or three who actually build completed motorcycles and ride them.

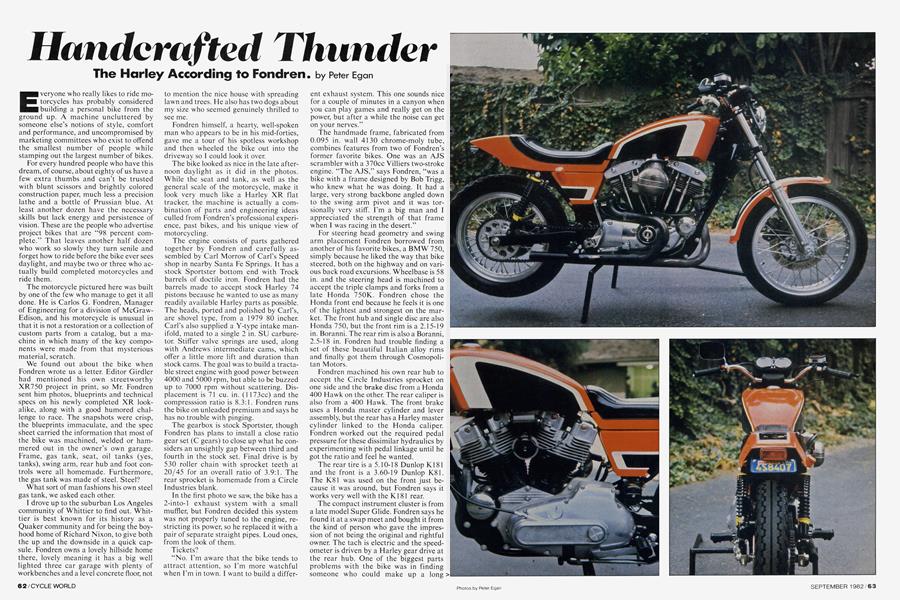

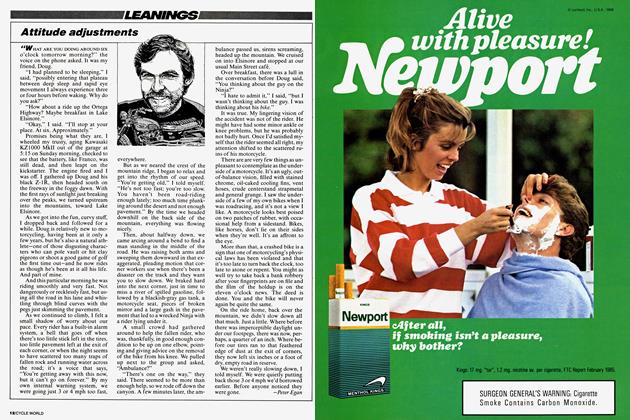

The motorcycle pictured here was built by one of the few who manage to get it all done. He is Carlos G. Fondren, Manager of Engineering for a division of McGrawEdison, and his motorcycle is unusual in that it is not a restoration or a collection of custom parts from a catalog, but a machine in which many of the key components were made from that mysterious material, scratch.

We found out about the bike when Fondren wrote us a letter. Editor Girdler had mentioned his own streetworthy XR750 project in print, so Mr. Fondren sent him photos, blueprints and technical specs on his newly completed XR lookalike, along with a good humored challenge to race. The snapshots were crisp, the blueprints immaculate, and the spec sheet carried the information that most of the bike was machined, welded or hammered out in the owner’s own garage. Frame, gas tank, seat, oil tanks (yes, tanks), swing arm, rear hub and foot controls were all homemade. Furthermore, the gas tank was made of steel. Steel?

What sort of man fashions his own steel gas tank, we asked each other.

I drove up to the suburban Los Angeles community of Whittier to find out. Whittier is best known for its history as a Quaker community and for being the boyhood home of Richard Nixon, to give both the up and the downside in a quick capsule. Fondren owns a lovely hillside home there, lovely meaning it has a big well lighted three car garage with plenty of workbenches and a level concrete floor, not to mention the nice house with spreading lawn and trees. He also has two dogs about my size who seemed genuinely thrilled to see me.

Fondren himself, a hearty, well-spoken man who appears to be in his mid-forties, gave me a tour of his spotless workshop and then wheeled the bike out into the driveway so I could look it over.

The bike looked as nice in the late afternoon daylight as it did in the photos. While the seat and tank, as well as the general scale of the motorcycle, make it look very much like a Harley XR flat tracker, the machine is actually a combination of parts and engineering ideas culled from Fondren’s professional experience, past bikes, and his unique view of motorcycling.

The engine consists of parts gathered together by Fondren and carefully assembled by Carl Morrow of Carl’s Speed shop in nearby Santa Fe Springs. It has a stock Sportster bottom end with Trock barrels of doctile iron. Fondren had the barrels made to accept stock Harley 74 pistons because he wanted to use as many readily available Harley parts as possible. The heads, ported and polished by Carl’s, are shovel type, from a 1979 80 incher. Carl’s also supplied a Y-type intake manifold, mated to a single 2 in. SU carburetor. Stiffer valve springs are used, along with Andrews intermediate cams, which offer a little more lift and duration than stock cams. The goal was to build a tractable street engine with good power between 4000 and 5000 rpm, but able to be buzzed up to 7000 rpm without scattering. Displacement is 71 eu. in. (1173cc) and the compresssion ratio is 8.3:1. Fondren runs the bike on unleaded premium and says he has no trouble with pinging.

The gearbox is stock Sportster, though Fondren has plans to install a close ratio gear set (C gears) to close up what he considers an unsightly gap between third and fourth in the stock set. Final drive is by 530 roller chain with sprocket teeth at 20/45 for an overall ratio of 3.9:1. The rear sprocket is homemade from a Circle Industries blank.

In the first photo we saw, the bike has a 2-into-l exhaust system with a small muffler, but Fondren decided this system was not properly tuned to the engine, restricting its power, so he replaced it with a pair of separate straight pipes. Loud ones, from the look of them.

Tickets?

“No. I’m aware that the bike tends to attract attention, so I'm more watchful when I’m in town. I want to build a different exhaust system. This one sounds nice for a couple of minutes in a canyon when you can play games and really get on the power, but after a while the noise can get on your nerves.”

The handmade frame, fabricated from 0.095 in. wall 4130 chrome-moly tube, combines features from two of Fondren’s former favorite bikes. One was an AJS scrambler with a 370cc Villiers two-stroke engine. “The AJS,” says Fondren, “was a bike with a frame designed by Bob Trigg, who knew what he was doing. It had a large, very strong backbone angled down to the swing arm pivot and it was torsionally very stiff. I’m a big man and I appreciated the strength of that frame when I was racing in the desert.”

For steering head geometry and swing arm placement Fondren borrowed from another of his favorite bikes, a BMW 750, simply because he liked the way that bike steered, both on the highway and on various back road excursions. Wheelbase is 58 in. and the steering head is machined to accept the triple clamps and forks from a late Honda 750K. Fondren chose the Honda front end because he feels it is one of the lightest and strongest on the market. The front hub and single disc are also Honda 750, but the front rim is a 2.15-19 in. Boranni. The rear rim is also a Boranni, 2.5-18 in. Fondren had trouble finding a set of these beautiful Italian alloy rims and finally got them through Cosmopolitan Motors.

Fondren machined his own rear hub to accept the Circle Industries sprocket on one side and the brake disc from a Honda 400 Hawk on the other. The rear caliper is also from a 400 Hawk. The front brake uses a Honda master cylinder and lever assembly, but the rear has a Harley master cylinder linked to the Honda caliper. Fondren worked out the required pedal pressure for these dissimilar hydraulics by experimenting with pedal linkage until he got the ratio and feel he wanted.

The rear tire is a 5.10-18 Dunlop K181 and the front is a 3.60-19 Dunlop K81. The K81 was used on the front just because it was around, but Fondren says it works very well with the Kl 81 rear.

The compact instrument cluster is from a late model Super Glide. Fondren says he found it at a swap meet and bought it from the kind of person who gave the impression of not being the original and rightful owner. The tach is electric and the speedometer is driven by a Harley gear drive at the rear hub. One of the biggest parts problems with the bike was in finding someone who could make up a long > enough cable and sheath to reach all the way from the rear wheel to the speedometer. Fondren reports he was not undercharged for that particular component.

Some pieces that didn’t cost much but took plenty of work to produce are the seat, gas tank and the twin oil tanks. The steel handmade gas tank was most intriguing. It was as perfect as any factory tank and had no visible seams or flaws. I asked Fondren how a person goes about making a gas tank.

“You make a lot of noise and do a lot of pounding with a hammer,” he said. “I made a cardboard mockup of the tank, then laid the pattern out on steel sheet and cut the pieces with a bandsaw.” The tank is made of two side pieces and a single top piece, shaped and then welded together. Fondren shaped the pieces by hammering the steel panels out over sandbags. When the shape was roughly correct he pounded out the high spots with a dolly and body hammer, then used a rotary sander to get the surface smooth. The seams were gas welded and final sanding was done by hand. Fondren did his own painting and admits to using a couple of small spots of Bondo on welding pits that would have required too much grinding to remove. His near apology for this transgression was wasted on a person who has reconstructed entire cars out of body filler, for want of metalworking skills.

Fuel capacity is about 4.1 gal., giving the bike nearly 200 mi. between fill-ups. Normal mileage averages about 50 mpg, though it can drop into the mid-40s if the bike is ridden with great verve on Sunday morning; talking with Fondren, I gather it often is.

The bike has two steel oil tanks, made the same way as the gas tank. They are linked by a hose and the battery nestles between them. Total oil capacity, with the oil cooler mounted, is 3 qt. The XR-looking seat is also made of welded up steel pieces forming the pan and tailpiece beneath the upholstery. The same factoryperfect finish is evident in the construction of the seat.

It is possible, of course, to put a bike together from beautiful, high quality components and have them so far out of harmony that riding the machine is no fun at all. Private builders have done it and so have big factories. So 1 was anxious to ride the bike and see how it worked.

Fondren kicked the big Harley through once or twice, then switched on the ignition and gave it a healthy jab. It started right up and settled down to a loud and steady idle, shuffling along Harley style. I got on the bike and he reminded me it had a right side shift, with one up and the rest down pattern. I put it in first with a light touch of the pedal and took off.

Out on the street the bike was a delight to ride, a wonderful contradiction to its own terms. The engine is powerful and loud, alternately bellowing and rapping off, an instant reminder of all the relatively unmuffled bikes I rode in the Sixties, when motorcycles were expected to make noise. There is considerable vibration all the way up, with a smooth area around 3200 rpm (Fondren had warned me I might find the bike “a bit of a jackhammer”). Throttle response through the big SU carb is perfect, asphalt-grabbing torque is instantaneous. Yet for all the hairy feel and sound of the engine, the controls are quite unHarleylike. Shifting, clutch engagement and braking—in fact all movement of the controls and levers— are perfectly smooth and precise, reminding me more of a Ducati 900 than anything else I've ridden. There is a firm, mechanical feel with no slop or vagueness. A well knitted together bike.

Handling is light and precise, and cornering clearance abundant. The bike feels lighter than its 430 lb. and is not in the least topheavy, giving the side-to-side maneuvering feel of a motorcycle with a low c.g. In size and agility the bike is similar to a Honda Ascot, but with chunkier, more solid feel to the whole machine. It also vibrates more than an Ascot, is louder, and has a few extra truckloads of horsepower.

When I pulled back into the driveway with the bike and Fondren asked me what I thought, the two simple words that immediately came to mind were fun and exciting.

It was getting dark out, so we pushed the bike into the garage. Fondren made some coffee and we sat down to talk about bikes, in general and this one in particular. The views and perceptions of people who build their own motorcycles are always intriguing, especially to one who spends a lot of time testing and riding the manufactured product.

Fondren told me he'd been motorcycling for about 12 years. His first bike was the AJS/Villiers, which he used for desert racing. After that he bought a 1973 CB750 Honda, which he sold after 100 mi. of riding. “It wasn’t my kind of motorcycle,” he told me. “It had no torque and you had to buzz its brains out to make power, and it was enormously heavy for what it was.” Next came a Yamaha TX750, the old troubled Twin. “The biggest problem with the TX750 was just plain rotten engineering. I didn’t have as much trouble as some people did with that bike, and I put a lot of miles on it. But Yamaha should have done a lot more testing and development before they brought it out. . .”

He sold the TX and bought the BMW 750. “I put on 33,000 mi. in 16 months. That was the most fun I’ve had on a motorcycle. I took it on camping trips up to Oregon and even rode the thing on logging trails. I’d ride back into a remote campsite and people with four wheel drive trucks and dirt bikes couldn't believe I was in there on a BMW. I sold the bike just because I’d piled up so many miles on it.”

After that he bought a 1977 Harley Low Rider. “This bike had so many serious problems, Harley actually bought it back from me. The rear brakes heated up and locked as I was heading down a freeway ramp because the rear master was defective. The primary sprocket sheared off at 3000 mi., and it quit running so many times in the middle of the freeway, I was afraid I’d get run over by a truck. When Harley took the bike back, I had 4400 mi. on the bike and my wife had put 1 200 retrieval miles on our pickup truck. I was always calling her from somewhere.”

After that he bought a Yamaha XS11 for touring and just getting around. The Yamaha, with fairing and saddlebags, is still in his garage. “It has a wonderfully strong motor,” Fondren says of the Yamaha, “but in a corner you never know where the wheels are. It’s a strong, useful bike, but it’s not fun. That’s why I built the Harley. I thought if I built a Harley myself I could make it completely reliable. But that hasn’t been the case. No matter how you tighten or lock things, the engine vibration still loosens them up. I gc over the bike every 150 to 200 mi. just to make sure everything is tight. It’s good for about one run to the Rock Store before it needs a little maintenance.”

Fondren says he thinks Harleys have become quite a bit more reliable in the past few years, and he’s glad to see it. Typically, his admiration for Harley-Davidsons is focused on the look and sound of the engine. In describing the appeal of the big V-Twin, comparisons with aircraft engines worked their way into the conversation, a vision of the Harley as two cylinders from a radial airplane motor. “I guess what I’ve tried to build,” Fondren said grinning, “is a roadgoing version of the Stearman biplane.”

As a person who has spent about half his life trying to bum Stearman rides at the local airport, I could appreciate that sentiment. A Stearman biplane, after all, is an old design, a fabric-covered aircraft with open cockpits. It is noisier, windier, thirstier, more difficult to fly well and harder to maintain than a modern Cessna or Piper.

If you want to fly it a long way you have to suffer a little bit. In exchange for all that inconvenience the airplane looks right, sounds good and is fun to fly. And there is history in that big radial engine.

When I left Fondren’s house we agreed to get together for a Sunday morning ride during which we would exchange bikes. He could ride my Ducati if I could ride his Harley. I wanted to get the bike out on a empty mountain road, instead of just riding it around the city.

Call it my roadgoing version of bumming a Stearman ride at the local airport. B3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue