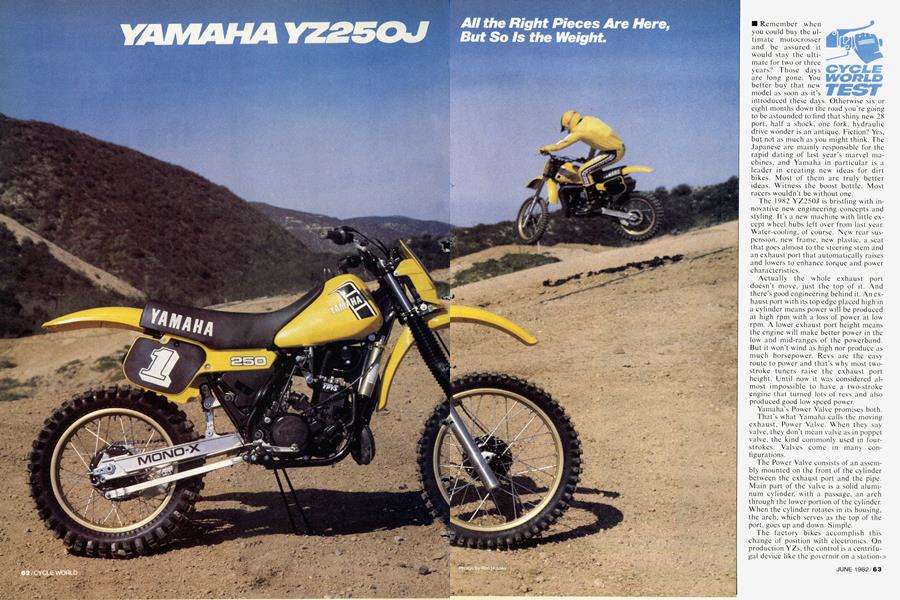

YAMAHA YZ250J

CYCLE WORLD TEST

All the Right Pieces Are Here, But So Is the Weight.

Remember when you could buy the ultimate motocrosser and be assured it would stay the ultimate for two or three years? Those days are long gone. You better buy that new model as soon as it’s introduced these days. Otherwise six or eight months down the road you’re going to be astounded to find that shiny new 28 port, half a shock, one fork, hydraulic drive wonder is an antique. Fiction? Yes, but not as much as you might think. The Japanese are mainly responsible for the rapid dating of last year’s marvel machines, and Yamaha in particular is a leader in creating new ideas for dirt bikes. Most of them are truly better ideas. Witness the boost bottle. Most racers wouldn’t be without one.

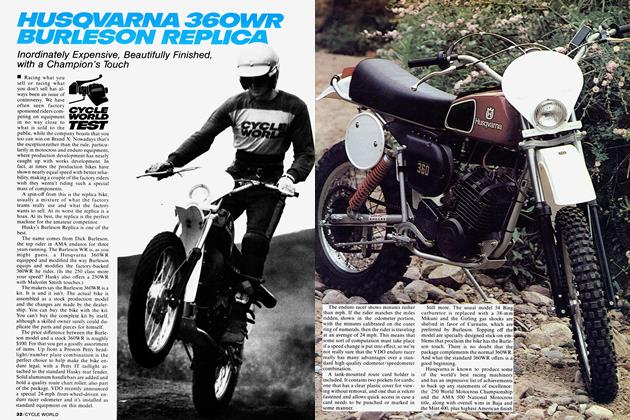

The 1982 YZ250J is bristling with innovative new engineering concepts and styling. It’s a new machine with little except wheel hubs left over from last year. Water-cooling, of course. New rear suspension, new frame, new plastic, a seat that goes almost to the steering stem and an exhaust port that automatically raises and lowers to enhance torque and power characteristics.

Actually the whole exhaust port doesn't move, just the top of it. And there’s good engineering behind it. An exhaust port with its top edge placed high in a cylinder means power will be produced at high rpm with a loss of power at low rpm. A lower exhaust port height means the engine will make better power in the low and mid-ranges of the powerband, But it won't wind as high nor produce as much horsepower. Revs are the easy route to power and that’s why most twostroke tuners raise the exhaust port height. Until now it was considered almost impossible to have a two-stroke engine that turned lots of revs and also produced good low speed power.

Yamaha’s Power Valve promises both.

That’s what Yamaha calls the moving exhaust, Power Valve. When they say valve, they don’t mean valve as in poppet valve, the kind commonly used in fourstrokes. Valves come in many configurations.

The Power Valve consists of an assembly mounted on the front of the cylinder between the exhaust port and the pipe. Main part of the valve is a solid aluminum cylinder, with a passage, an arch through the lower portion of the cylinder. When the cylinder rotates in its housing, the arch, which serves as the top of the port, goes up and down. Simple.

The factory bikes accomplish this change of position with electronics. On production YZs, the control is a centrifugal device like the governor on a stationary engine. The power valve is springloaded in the down, or low-rev position.

As the engine picks up speed the control spins its weights outward. This force works against the spring and rotates the power valve’s arch. As speeds drop, so does the arch. The best of both exhaust heights, you could say.

The 250’s water-cooling looks like a direct transfer from the '81 YZ125; the radiator is on the triple clamps and a lot of plumbing is used to route the coolant.

Cooled coolant comes out of the bottom of the radiator, into the lower triple clamp, through the bottom of the steering stem, down the front downtube and then through a rubber hose to the primary driven water pump. Another hose takes the water from the pump to the front of the head. Water circulates around in the head and cylinder and out the rear of the head, to yet another rubber hose to the upper left side of the frame’s steering head. From here the water enters the frame tube, then back into the steering stem (but doesn’t mix with the cold water in the bottom of the stem because of a plate that separates the top of the stem from the bottom), then into the top triple tree and back to the radiator via a short rubber tube, whew. All in all, it’s the most complicated of all the water-cooled bikes except Yamaha’s 125.

Other changes have taken place inside the engine. Transmission gears and ratios are the same as last year as is the clutch. The primary drive, helical gear on past models, is now a more efficient but noisier straight-cut gear. Center cases are also new, mainly to accept the power valve mechanism. Ignition is still an internal rotor CDI without lighting coil. A 38mm Mikuni carb feeds gas through a six-petal reed.

Looking the rest of the bike over will confirm the duplication of many parts used on Yamaha’s YZ490 motocrosser. Basically the frame is the same with variations in engine mounting tabs, a steeper head angle on the 250; 27.5 ° compared to 28.5° on the 490. And the 250 has a different front downtube, a wishbone design to accommodate the center exhaust port. Gusseting is generous and center frame triangulation is good.

Shock placement is much like last year’s YZ250. The front of the shock mounts about the middle of the frame’s backbone with the shock sitting above the frame tube. The rear bolts to the new Monocross rear suspension that provides a rising-rate action. Thus, in theory anyway, the suspension can react easily to small bumps while not bottoming on the large ones. The three rearmost joints on the system are equipped with grease fittings but the front two require disassembly for maintenance. The boxed aluminum swing arm has lost its built-in triangulation and no longer looks like monos of past years. The new arm has exceptional strength due to its basic shape and is further beefed by liberal use of gussets.

Every year sees a new rear shock on YZs. 1982 is no different. And it’s more adjustable than any shock on the market except the Fox Twin-Clicker used as standard equipment on KTMs. The YZ shock offers adjustments for compression and rebound damping. Compression damping can be adjusted to 20 positions, rebound damping to 25 positions. Rebound is adjusted in front and above the rear wheel like past models. Compression damping isn’t quite as easy and requires a long, flat-blade screwdriver and removal of the front tank screws. The excellent owner’s manual explains the adjustment procedures well. Be sure to read it carefully if you buy a new Yamaha YZ, it’s worth the time. Shock oil capacity is larger for ’82, the direct result of a 1 mm larger shock body and a longer aluminum reservoir. The reservoir has oil on top and nitrogen below. Separation of oil and nitrogen is by an aluminum piston.

Adding rigidity to the strong frame and swing arm is a set of KYB forks with 43mm stanchions. Like the units on the ’82 YZ490, the lower legs are aluminum tubes with a welded-on bottom cap. Normal adjustments, air, oil volume and weight, and stanchion tube height are offered. No compression or rebound damping adjustments are available.

Wheels and brakes are normal good Yamaha stuff. Aluminum rims, large spokes, strong hubs, and stronger brakes. The front is the same double-leading shoe model from last year, the rear is a single leading shoe with a rectangular aluminum static arm that keeps rear suspension lock-up and wheel chatter to a minimum.

Major body parts look different from what other makes are using for ’82. The seat extends over the tank so the rider can sit on the seat, not on the tank, when going around a tight corner. The plastic tank has a recessed top so the seat doesn’t protrude too much and the front of the seat has a hook under it so it doesn’t move around when the rider climbs out on it. All dirt bikes will probably look like this before long. It makes sense.

Plastic parts are quality items you won’t have to throw away before riding the bike. The fenders look nice and protect the rider fairly well. The side panels fit and the pipe doesn't burn through.

All the small but important items that make a motorcycle worth the bucks are all top rate on the YZ250J. Handlebars are the right shape and width, grips are fine, the throttle a straight pull that’s gear driven, the rear brake lever has a claw top and the shift lever has a folding tip. Additionally, cables are well routed and the cables are generally the best on the market. They have large bodies and they’re nylon lined.

Sitting on the bike, blipping the throttle while the water warms, the rider becomes aware of the front numberplate sticking way out there. One rider said it looked like a TV set on the triple clamps. The sound deadening effect of the water jacket around the cylinder gives the engine a distinctive tone and there’s definitely a different sound to the exhaust when the engine is blipped high enough for the power valve to engage.

Starting away on the first ride it’s quickly apparent the bike is geared internally for motocross. First gear is tall and there’s almost no low end power. Wait a minute, isn't the power valve supposed to be the solution for lack of low end? Anyway, forget the first quarter throttle, nothing happens in that range. Nothing. After the first quarter, power starts building rapidly. The power can be described as more like a 125, a really strong 125. Enough for most 250 race courses and classes to be sure, but still very much like a 125.

Gear spacing is correct and the engine doesn’t bog or fall off the powerband as long as the throttle is kept open. If it drops into that first quarter the bike will still run and it’ll move along happily at trail speeds while in this range, but don’t try and race without the throttle mostly open.

Water cooled engines cool down quickly, so if the bike sits for three or four minutes it’ll restart better if you use the choke.

Water cooling adds weight. So does the Power Valve, and we suspect the new Monocross suspension brings a few pounds as well. This is progress and it’s technical advancement, but still, it's extra weight.

And it all adds up. Probably because many components are shared with the YZ490, the 250 weighs only 3 lb. less than the open class racer. With half a tank of fuel the YZ250 tips the scales at 243 lb. while its closest competition, the water-cooled Suzuki RM250 weighs 226 lb. and the air-cooled Kawasaki KX250 is 228 lb. It may be that the Yamaha has extra strength, or that Suzuki and Kawasaki have spent more time paring down parts, but in either case, the YZ is the heavyweight of the group.

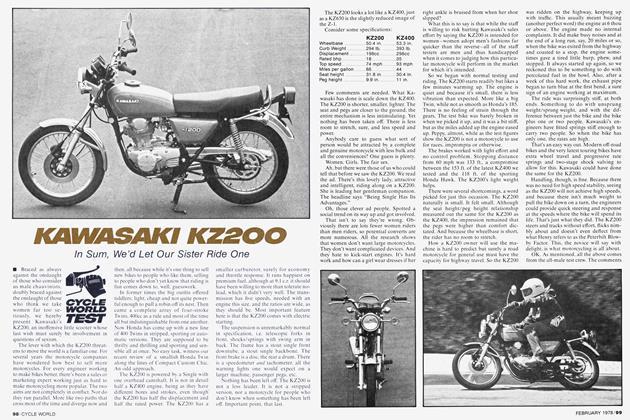

YAMAHA YZ250J

$2179

Reversing that, riding the YZ gives a different impression. The bike doesn’t feel that heavy and it feels nothing like the YZ490, never mind that it’s got the same wheel travel and the same swing arm length, or that the Yamaha’s single shock is mounted high in the frame. There’s some of the 490’s topheavy feeling, but the 250 isn't as ponderous and the steering isn’t nearly as slow.

Why not? Simple. The 250’s steering rake angle is one degree steeper than the 490’s, and that seemingly small detail is enough to let the 250 turn easier and quicker and to mask the weight. The scales are correct, but the only time it shows is when you’re grunting the 250 onto a milk crate or into the truck.

Even the rear suspension, something we didn’t like on the 490, worked well. Not as good as the KX or RM, but well. Some kick is apparent on square-edged holes but not to the extent the 490 has. Living with the bike for several months so one could take the time to fully experiment with different combinations of rear suspension adjustment could result in dialing out most of our complaints. So many adjustments actually bring up another problem. How many people will ever take the time to fully adjust a suspension with so many variables?

We turned up a weird handling quirk on smooth corners. Going into a smooth TT-type corner, fast or slow, the rear wheel will suddenly kick out. It happens without warning. Boom, the rear wheel is sliding like a flat track bike. The back never passed the front and never tried. It would just kick out so far, instantly. It even happened to one tester while the throttle was off! It’s startling the first time it happens but doesn’t seem to have any killer instinct. In fact it’s rather enjoyable when playing flat tracker on fire roads. We never did have it happen on rough ground or a motocross course so it’s nothing to worry about. Just be prepared if you go riding in an area that has smooth corners.

We worried a little about the complexity oí the water-cooling on our test bike. The water hoses stick out around the pump and look especially vulnerable to other riders’ footpegs and course hazards. We never snagged one or had any leakage problems. And the rest of the bike never gave one minute of trouble. Stone reliable.

Okay, so it’s heavy and it’s complex. It’s also a good machine. Nothing will need discarding before it can be raced and if our bike was an indication of the rest of them, you won’t spend all of your waking hours repairing it. That’s probably worth a little extra weight.