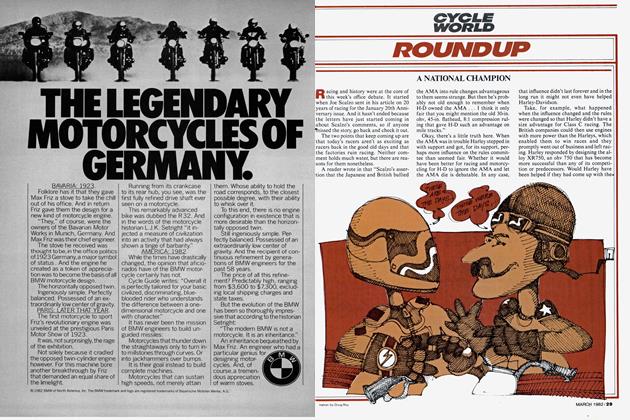

BMW R65LS

CYCLE WORLD TEST

What’s a Paint Job Like This Doing on a BMW?

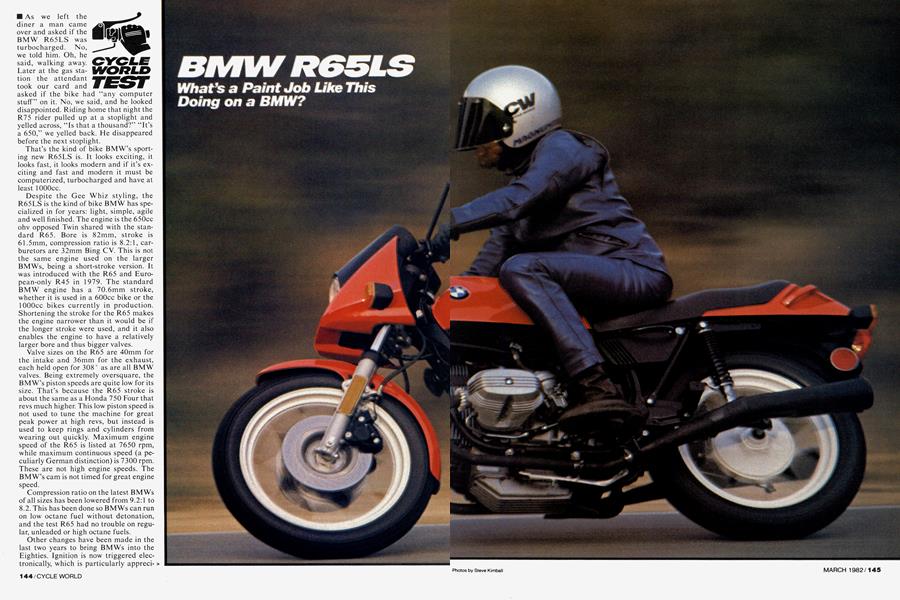

As we left the diner a man came over and asked if the BMW R65LS was turbocharged. No, we told him. Oh, he said, walking away. Later at the gas station the attendant took our card and asked if the bike had “any computer stuff” on it. No, we said, and he looked disappointed. Riding home that night the R75 rider pulled up at a stoplight and yelled across, “Is that a thousand?” “It’s a 650,” we yelled back. He disappeared before the next stoplight.

That’s the kind of bike BMW’s sporting new R65LS is. It looks exciting, it looks fast, it looks modern and if it’s exciting and fast and modern it must be computerized, turbocharged and have at least lOOOcc.

Despite the Gee Whiz styling, the R65LS is the kind of bike BMW has specialized in for years: light, simple, agile and well finished. The engine is the 650cc ohv opposed Twin shared with the standard R65. Bore is 82mm, stroke is 61.5mm, compression ratio is 8.2:1, carburetors are 32mm Bing CV. This is not the same engine used on the larger BMWs, being a short-stroke version. It was introduced with the R65 and European-only R45 in 1979. The standard BMW engine has a 70.6mm stroke, whether it is used in a 600cc bike or the lOOOcc bikes currently in production. Shortening the stroke for the R65 makes the engine narrower than it would be if the longer stroke were used, and it also enables the engine to have a relatively larger bore and thus bigger valves.

Valve sizes on the R65 are 40mm for the intake and 36mm for the exhaust, each held open for 308° as are all BMW valves. Being extremely oversquare, the BMW’s piston speeds are quite low for its size. That’s because the R65 stroke is about the same as a Honda 750 Four that revs much higher. This low piston speed is not used to tune the machine for great peak power at high revs, but instead is used to keep rings and cylinders from wearing out quickly. Maximum engine speed of the R65 is listed at 7650 rpm, while maximum continuous speed (a peculiarly German distinction) is 7300 rpm. These are not high engine speeds. The BMW’s cam is not timed for great engine speed.

Compression ratio on the latest BMWs of all sizes has been lowered from 9.2:1 to 8.2. This has been done so BMWs can run on low octane fuel without detonation, and the test R65 had no trouble on regular, unleaded or high octane fuels.

Other changes have been made in the last two years to bring BMWs into the Eighties. Ignition is now triggered electronically, which is particularly appreciated on the BMW because setting the points on a BMW used to be more of a bother than it should have been. Fortunately ignition timing is still adjustable, unlike some other bikes with electronic systems. That can be appreciated if a particular machine is prone to detonation or can run with increased advance at high elevations.

To meet emission rules BMW has added an air breather to the exhaust ports, much like the system used by Kawasaki. This helps oxidize the emissions in the exhaust so the carbs don’t have to be leaned out excessively. At least in theory they don’t have to,be leaned out too much. The parts to adapt the exhaust breather to the BMW are simple enough, some one-way valves and steel tubes connecting the exhaust ports with the new airbox. Older BMWs used a cast aluminum chamber above the transmission to house the air filter. Now there’s an easily removable flat paper filter housed in a plastic chamber installed where the old casting used to be. The new airbox also includes breather tubes routing blowby from the crankcase to the intake tubes between the airbox and the carburetors.

Last year’s major changes to the engine were the addition of all-alloy cylinders and a new clutch. The cylinders are a high silicon alloy with a nickel bore surface. According to BMW the new cylinders, used on all the BMW models, are three times better for heat transfer than the steel-lined cylinders, plus needing less break-in and having reduced oil consumption. All that and the new cylinders are 6 lb. lighter than the steel-lined cylinders.

Like the new cylinders, the clutch change was introduced last year on all the BMWs. The new clutch is 8 lb. lighter than the clutch used on the big BMWs, plus it uses a diaphragm spring pressure plate for more positive action and lighter clutch pull. It is still a single plate dry clutch.

What hasn’t been changed is the chassis. When the R65 was introduced it had the first new BMW frame and suspension in years. The double downtube cradle frame used smaller round tubing for the main section and had a different bolt-on rear section than the big BMW frame. The forks were an entirely new straightleg design with substantially different suspension qualities than the leading-axle forks on the bigger BMWs. Travel was only 6.8 in. instead of 8.2 in. as used previously. And the fork spring on the 650 BMW is a single rate moderate tension spring instead of the double rate too-soft primary and firm secondary. When the R65 was introduced it was the best handling stock BMW, being easier to control than the large BMWs because the suspension didn’t allow the bike to discover as many unusual attitudes as the older long-travel suspension.

Apparently the new style suspension has satisfied BMW because the new large BMWs now have forks that work more like the R65 forks. And the new larger BMWs have also moved the front brake master cylinder from under the gas tank to the handlebars, where it doesn’t need to be cable-actuated. Enhancing the braking ability of the LS is the addition of a second disc brake on the front wheel. Both discs are 10.25 in. across, drilled for lightness, and grabbed by Brembo calipers. Combined with the 1mm smaller master cylinder bore used on the LS, the braking power of the machine is excellent.

An 8.7 in. drum is used for a rear brake on the LS, a particularly good choice. It is strong enough for the job, easily controlled, works in the rain and, in conjunction with the driveshaft assembly on the righthand side of the swing arm, it enables the rear wheel to be pulled with less time and effort than any other street bike.

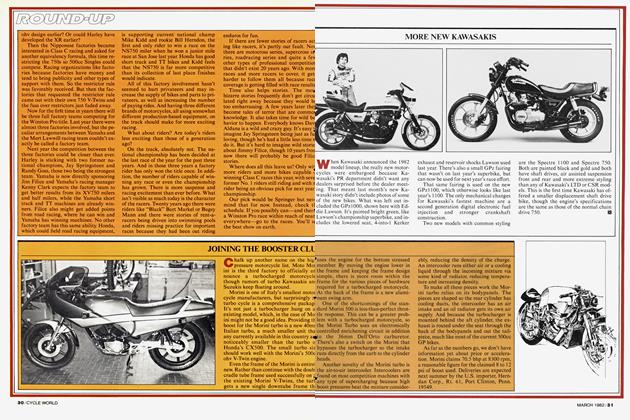

At both ends of the LS are wheels quite unlike anything that’s ever appeared on a motorcycle before. Lirst, they are antiseptic white. People who see the wheels are inclined to touch them to see if they are plastic, they are so clean and lightlooking. Construction of the wheels is accordingly unusual. Rims are hardened aluminum. The spokes are cast of a softer alloy so the wheels have some flex while possessing adequate rim strength. In shape the wheel spokes are built out of two shapes, five elongated ovals in the center of the wheel tied to five triangular shapes of spoke extending to the rim. The white surface is hard enough to resist scratching and chipping in normal use and is smooth enough so it can be cleaned more easily than normal cast wheels. Rim diameter is 18 in. at both ends, 1.85 in. wide in front and 2.50 in. wide in back. Tubes are used in the Continental tires.

As nice as the mechanical components of the motorcycle are, it is the appearance that makes this bike. And nothing contributes more to the stunning appearance of the LS than the brilliant red paint. This is not fire engine red, or Italian motorcycle red. It’s brighter than any other red, with just a touch of orange to the color. On the BMW it is also perfectly applied to the pleasantly large 5.8 gal. gas tank, the molded plastic front fender, the plastic tailpiece and the plastic cow catcher around the headlight. Most of these components would probably be embarassed to be called plastic. They don’t look plastic any more than the wheels look like aluminum. Take the front fender, for instance. It’s stiff and feels like a well-made stamped steel fender. Only the edges aren’t rolled under. Thinking the fender was cast metal, we examined it with a magnet to see if it was steel. It wasn’t. The piece is nothing like the plastic fenders found on other bikes. It is solid enough it could work as a fork brace. And the finish is perfect.

If the cow catcher looks related to something on a Suzuki Katana, you have an astute eye. The design concept comes from the same man. Only the BMW is much more subdued, as a BMW should be. BMW claims the mini-fairing reduces front end lift by a third while improving riding comfort. The black plastic shield that continues above the headlight, then folds down to enclose the instruments and continues on down around the handlebars might just do something to break up some wind to hit the rider. Then again, it might not. Any difference is so slight riders weren’t aware of any protection. What is obvious is that no other fairing or windshield will fit on the LS with the cow catcher in place. Removing the nose isn’t easy either, as it forms the instrument housing. It would take a callous person to make that change to the bike’s appearance. Sort of like giving Meryl Streep a nose job so she could wear glasses more easily.

Another piece on the LS that establishes its appearance is the seat. It’s black and covered in the usual naugaskin, but it doesn’t have a pattern that looks like your wife accidentally left a hot waffle iron on the seat. There is no stitching or embossed pattern, and there’s no grab strap running across the seat right where you want to sit. This is probably the cleanest design on a seat ever. It’s padded a little better than some other BMW seats, though it’s not pillow-soft. And the passenger can use grab handles built into the tailpiece if they are necessary.

Lifting the hinged tailpiece is easy enough after pushing a button. It can be locked, but that’s not mandatory. Under the seat is a larger storage bin at the back of the motorcycle and a large bin behind the gas tank for tools. BMW is one of the very few motorcycle companies that doesn’t put a few imitation tools into a> plastic bag exactly big enough for all the tools except for the pliers.

No longer does BMW include tire patching equipment in the tool kit, but all these nice BMW tools are still there except for the air pump, tire irons and patch kit. And those parts are optional. Even the tire pump mounting lugs are still on the bike. During testing the rear tire picked up a nail and we had the opportunity (?) to notice some nice attention to details when changing it. The rear tire can be removed in about a minute by removing one nut and loosening one bolt. As the tire slips off the splines the machine pivots forward, resting on the front tire. Even changing the tire in our own shop we used the BMW’s tool kit because it was just as convenient as using our own tools. Because the tires have tubes, it is easier to break the bead on the BMW tires than on most of the tubeless designs. There is an inner lip on the rims to keep the tire in place when flat, a good safety feature, but it doesn’t interfere much in tire changing. The smooth white surface makes easy work of running the tire on and off the rim, but the edges get chipped easily with any normal tire irons.

Most basic maintenance on the BMW is so easy as to be inviting. Rocker arm covers come off with one bolt. Valve lash is easily adjusted with simple tools and there are only four valves to adjust. Even changing the air filter doesn’t require any tools.

Accentuating the ease of service is the wonderful owner’s manual. Most motorcycle owner’s manuals have become nothing more than defenses in product liability suits, filled with lots of warnings and cautions and notes, but no information about how to maintain a motorcycle. Not this one. The explanations are clear and understandable. Photos are well done. The warnings in this manual are reasonable and worth reading. There are even recommendations on extra parts that might be needed on an extended journey. Service procedures are explained for checking and changing all fluid levels, for changing brake pads, checking wheel bearings, removing wheels, changing tires, replacing light bulbs, adjusting valves, checking the timing, adjusting carburetors and numerous other routine chores. Even torque figures are included for most major bolts and tightening sequences are listed for head bolts. These may not be things all owners will want to tackle, but it is information that BMW trusts its owners with and we only wish more motorcycle companies would do so.

As modern and well thought out as the R65LS is, it is not a motorcycle that can be ridden without adaptation by the rider. All BMWs have quirks that riders of other brands usually find disconcerting at first. Some of the quirks turn out to be appreciated features later on, and some of them remain nuisances.

Most unusual of the bike’s characteristics is the seating position. It is sporting in a way that Japanese bikes even with red paint have not discovered. The handlebars are low and narrow, with little rise. The pegs do not fold and are thus placed relatively high, though they may be adjusted on their mounts. One does not sit bolt upright on this bike without having spent prior time on the rack. There are no arms that long.

So the LS rider leans forward. This works well when the bike is on the road, in top gear, going at speeds where the winds of motion help support the rider. For that kind of riding the position is correct. At lower speeds a rider must hold himself up in a semi-pushup position. That can be tiring. The riding position combines with the short bars and the bike’s quick steering to surprise first-time riders. These are not bars that can be pulled to steer the bike. Instead, the rider’s weight is resting on the handlebars and normal pushing and pulling doesn’t produce the same amount of turn as on most other bikes this size.

This is only a factor for about a week of riding. After that a rider learns how the BMW likes to be steered, using forward motion on the bars to get surprisingly quick results. The LS is a quick steering bike and it is responsive, even though the efforts to produce that steering are somewhat higher than normal.

Suspension control helps the LS. This is not a foamy-feeling suspension. Spring and damping rates are well matched. The result is a taut suspension with plenty of travel for large bumps and dips but less compliance for small irregularities than many of the softer sprung Japanese bikes. That slightly stiffer suspension also enables the LS to handle the weight of a passenger.

How comfortable the bike is depends on the conditions. For freeway use the bike is not as plush as a GL500. But it is not a tiring bike to ride, being much lighter than a Silver Wing and more fun to fling around crooked roads. Vibration is noticeable, more so at around 4000 rpm than other speeds. It isn’t a great amount of vibration and, being a Twin, the frequency is low. It is also much smoother than conventional parallel Twins without counterbalancer shafts.

Controls are not all placed in the most convenient locations. Brake and clutch levers are fine and the efforts needed for operation are pleasantly low. The throttle return springs may be a trifle stiff. Worse is the position of the lefthand switches. In order to place the rearview mirror where it is in any way useful, the turn signal switch is much too low for easy reach. The horn is at the top of the control pod and is easily reached and the high beam switch, with its easy-to-use high beam flasher, is convenient enough. Perhaps on a bike with more normal handlebars the switch wouldn’t have to be twisted down so far for the mirrors to be used.

Other controls are fine. The ignition switch is right between the instruments where it’s easy to reach. Even a choke lever is installed at the left hand grip where it can be manipulated while the bike tries to start. This is a good thing, too, because the bike does not like running when it is cold.

Normal procedure is to give full choke and hit the starter button. The engine usually fires right up and then dies just as quickly. Giving a little gas helps. About six firings are needed to get the bike out of the driveway. This could stand some improvement.

When warm the engine fires right up and runs well. Well, it runs okay. Most of the time. There is, however, quite a lean spot at 4000 to 5000 rpm. Cruising at this speed, and it is a very common cruising speed, causes the bike to run as though it were running out of gas. Above 5000 rpm the engine runs especially well, revving freely and powerfully. Low rpm power is adequate, but not extraordinary. For-

tunately there is still ample flywheel, so the machine can be accelerated from idle, in gear. Power is good, with quartermile performance of 13.99 sec. at 93.16 mph. That’s substantially quicker than the 14.3 sec. quarter-mile time turned in by the original R65. Such performance figures may not cause much worry to owners of Japanese 650s who are interested in contests of speed, but it’s fast enough to be clearly out of the commuter-scooter class of motorcycles. This is the most cammy BMW produced. It likes to be revved up to redline, rattling its little pushrods in excitement, while the rider enjoys one of the nicest shifting transmissions in motorcycling.

This has not always been the case. BMWs used to be famous for noisy shifts and marginal clutches. The R65LS is

blessed with one of the lightest pulling clutches anywhere. It is also positive and strong. The transmission is equally competent, shifting without noise or effort.

So what sort of a bike is the R65LS? Call it a lightweight sport bike for grownups. It has performance that doesn’t show in quarter mile contests. It has handling that it doesn’t get to use on racetracks. It has styling that everyone notices and, as far as we’ve seen, everyone approves of.

This may not be as uniformly fine a bike as the standard R65 is. The seating position is not for everyone. But the excitement of its styling added to the satisfaction of its handling and its air of quality make it perhaps BMW’s most charming bike.

Yes, that’s the word for the bike. It’s charming.

BMW

R65LS

$3995