Riding the Winner

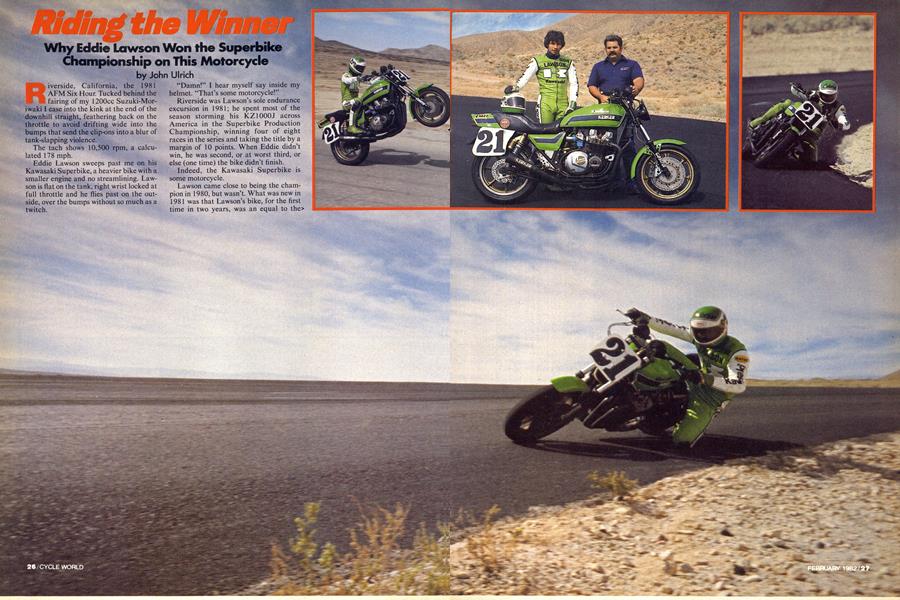

Why Eddie Lawson Won the Superbike Championship on This Motorcycle

John Ulrich

Riverside, California, the 1981 AFM Six Hour. Tucked behind the fairing of my 1200cc Suzuki-Moriwaki I ease into the kink at the end of the downhill straight, feathering back on the throttle to avoid drifting wide into the bumps that send the clip-ons into a blur of tank-slapping violence.

The tach shows 10,500 rpm, a calculated 178 mph.

Eddie Lawson sweeps past me on his Kawasaki Superbike, a heavier bike with a smaller engine and no streamlining. Lawson is flat on the tank, right wrist locked at full throttle and he flies past on the outside, over the bumps without so much as a twitch.

“Damn!” I hear myself say inside my helmet. “That’s some motorcycle!”

Riverside was Lawson’s sole endurance excursion in 1981; he spent most of the season storming his KZ1000J across America in the Superbike Production Championship, winning four of eight races in the series and taking the title by a margin of 10 points. When Eddie didn’t win, he was second, or at worst third, or else (one time) the bike didn’t finish.

Indeed, the Kawasaki Superbike is some motorcycle.

Lawson came close to being the champion in 1980, but wasn’t. What was new in 1981 was that Lawson’s bike, for the first time in two years, was an equal to the> Yoshimura Suzukis and the works Hondas. In 1981 Eddie Lawson won races the way he had in 1980—benefitting from attrition—but also in a way he hadn’t before—by taking charge and racing one on one against Wes Cooley and Freddie Spencer, the only two riders who could run with him.

Lawson credits the change in his fortunes to Rob Muzzy, 39, a dirt-track engine builder recruited by Kawasaki as lead mechanic in January, 1981. By mid-season Muzzy was crew chief in charge of engine development and Lawson’s Kawasaki had gained enough horsepower to win outright. Lawson responded by putting together a streak of consecutive victories— at Elkhart Lake, Loudon, Laguna Seca— followed by a second place at Pocono after starting last, and another win at Kent. To win the championship, all Lawson had to do was finish 11th at the final Daytona, and he crossed the line third.

I’m standing in the pits at windswept Willow Springs Raceway with the bike, Muzzy, Lawson, a Kawasaki public relations man, a mechanic, and two photographers. The racing season is over, the weather turning cold even in Southern California. I’m here to find out this motorcycle’s secrets, and I ask Muzzy about the engines Lawson uses. He tells me that the powerplants are basically as received from Kawasaki Heavy Industries (KHI), shipped from the Japanese factory in endurance racing trim.

“The major changes (we make) are in the cylinder head,” Muzzy says. “It’s the same casting, a Canadian model so it doesn’t have the (anti-pollution) air breather passageways, and it's reworked at our (Kawasaki Motors Corp., U.S.A.) shop. The KHI head is tricker. They have different combustion chambers, different valve angles, and use larger valves than we do. Our heads are ported differently, basically to a design of my own. It’s far from optimum, just the best we could do this year with the man hours w'e had available in between races. It’s been adequate. It’s done the job.”

Optimum or not, Muzzy is reluctant to detail precisely what he does to the cylinder head. Pressed, he will say that the secret is largely in the combustion chamber, and that he does not believe in mirror-polished ports, nor in ports deliberately roughed-up. The best port finish, according to Muzzy, is about the consistency of bead blasting, and is best achieved using about a 150 grit sandpaper roll on a porting tool.

Muzzy says his cylinder head work has been worth 20 horsepower over the course of the 1981 season (up to a current 150 bhp at 10,250 rpm) and he predicts more power for the 1982 races. He won’t talk about cam timing or lift, beyond saying that the same cams are used in works endurance bikes, but will admit that intake valve diameter is 38.5mm, the exhaust valve 32mm.

One KHI development that Muzzy uses is the installation of an extra, small D series NGK spark plug in each combustion chamber. “We’ve done dyno tests with and without it and there’s no difference,” says Muzzy, “but we’re able to run less ignition advance (32° BTDC) with two plugs than with one plug, and we have no detonation problems. The factory has a real problem getting race gas over there, so I’m sure that they have much more of a detonation problem than we would have here. I think that’s the main reason it was developed, and we’ve stuck with it because it’s worked well. There’s no reason to change.”

The 69 99mm pistons are forged by KHI in Japan and use three production Kawasaki rings; two compression rings and a three-piece oil control ring. Combined with the stock 66mm stroke, the bore brings displacement to 1015cc. Compression ratio is 10.2:1.

The pressed-together, roller-bearing crankshaft starts life as a production KZ1000J part, but is lightened 25 percent at the factory by removing material from the counterweights, and comes with special tapers on each end. (More on the tapers later). When Muzzy receives a modified crank from the factory, he spot welds the end of each pin/counterweight press fit to prevent twisting under power. Next, Muzzy masks off the main crank assembly and polishes the leading edge of each connecting rod, a process which he says prevents the rods breaking at high rpm.

“As the rods come they are just production connecting rods,” explains Muzzy.“We broke a rod at Talledega (in a heat race) and we broke a rod at Daytona (in practice), both at very high speed coming off the banking at high rpm. Evidently there was a stress concentration problem just below the wrist pin. Polishing those areas cured the problem. We’ve since run a number of high speed tracks, including Daytona, without any failures.”

Factory endurance bikes run the ignition on the left end of the crank and an alternator on the right. Muzzy cuts off the tapered left end of the crankshaft. The cases are built up with weld in the area around the crank end, then machined to accept an aluminum cap and O-ring, which fit over the cut-off crank end and seal in oil. Muzzy also welds up a pair of passageways at the bottom of the cases, which allow cooling oil to reach the alternator on stock engines.

On the right side, Muzzy modifies the cases to accept a special cast backing plate (built for the factory endurance race engines) carrying pickups for a KX80 CDI. The tapered right end of the crank accepts a stock KX80 magneto flywheel. Four double-lead KZ1000 MK11 coils are used, one for each cylinder’s two spark plugs.

The cams are driven by a standard linkplate (Hy-Vo) chain using stock slipper shoes and tensioner assembly.

The clutch is based on production parts but the backing plate is drilled to make it lighter and uses a KZ1100 (driveshaft) center hub. The KZI 100 clutch hub incorporates a spring-loaded ramp-and-cam torsional shock absorber. According to Muzzy, the clutch must be replaced every few races, but apparently sacrifices itself for the rest of the drivetrain, which has been dead reliable. The transmission has stock shafts but several different closeratio gearsets are made by the factory race department. Muzzy installs different transmission ratios depending upon the racetrack.

The countershaft sprocket cover is removed. A piece of aluminum pipe is welded onto the cases to support the shift shaft in the absence of the countershaft cover.

Final drive is Tsubaki 630 O-ring HST chain.

Lawson’s Kawasaki uses 36mm ET. flat-slide carburetors with Superbike-legal 31mm intake restrictors. The ET. carburetor was originally designed for singlecarburetor applications. Four ET. carbs bolted together and fitted with a dual-cable push-pull linkage produces a bank of carburetors too wide to fit on a stock Kawasaki head. So aluminum blocks were welded onto the race bike head and ported to match the cylinder head intakes with the carburetor throats.

Muzzy hasn’t found any carburetors which flow better than the ET.s but that doesn’t mean that the installation is perfect. Modulating engine speed at small throttle openings is a problem—the engine either doesn’t run or else races at 3000-4000 rpm, making an orderly trip through the pits difficult. “People look at you like you're some kind of an idiot,’’ complains Lawson, “because you’re riding through the pits with the engine racing.’’

“There are problems in the linkage setup,’’ admits Muzzy, “because they are an adapted carburetor, a single application made into a four-cylinder thing. The linkage leaves a lot to be desired. Right now it’s the best thing we’ve got. We’re working on it.’’

Like the stock KZ1000J and GPzl 100 engines, the engine in Lawson’s Superbike is rubber mounted in two places at the front of the crankcases and rigidly mounted at the rear of the cases, near the swing arm pivot. There isn’t an engine mount underneath the cases, and the mounting arrangement allows the engine to move in the frame. That movement broke exhaust pipe studs and flanges early in 1981. The cure was to build short spigots bolted rigidly to the cylinder head, then use smaller head pipes that slipped into the spigots and were secured by springs and, as a back-up, twisted safety wire. Each individual head pipe slips into the collector, again secured by springs, and the collector slips into the megaphone—once again held in place by springs. The megaphone is mounted to the frame with a standard GPzl 100 rubber biscuit mount.

Assembled and held with the springs, the exhaust system has enough flex to move with the engine and avoid being damaged.

The exhaust systembuilt by Kerker—is unusual in itself, beyond the spring mounting system. The head pipes are tapered, being made out of two stampings and welded together just like the tapered pipes used on motocross twostrokes. Head pipe diameter increases as the pipe travels from the cylinder head. According to theory, that head pipe configuration allows gases to expand as they travel from the exhaust port, and increases peak horsepower without sacrificing mid-range power.

The frame is amazingly stock. Extra brackets (as used for street parts) are ground off, but the steering head is stock and extra frame bracing is not added in the usual places. The single added gusset runs from the frame and supports the spool-shaped rear engine mount spacer located above the drive chain. Before the spacer was reinforced, engine torque unhindered by the flexible rubber front engine mounts—bent the rear mount bolt. Muzzy first tried a stronger bolt which wouldn’t bend, but then the frame cracked. The spacer reinforcing cured the problem.

The rest of the chassis consists of mostly special parts made in Kawasaki’s Santa Ana, California racing department shop. The tool-room pieces include the fork stanchion tubes (thinner wall, longer); fork damper rods (patterned after early model Kawasaki motocross dampers); upper and lower triple clamps (6061 aluminum in a variety of offsets for use at various tracks, the best offset for each track determined by extensive trial-and-error testing during 1980, and relieved underneath for lightness with a maze of supportive webbing left in place for strength); front brake discs (machined out of halfinch-thick iron billets, drilled and slotted, grooved around the edge and measuring 3 1 3mm when finished); front disc carriers (sliced out of magnesium); front caliper hangers (aluminum, drilled); rear disc carrier (magnesium); rear caliper hanger (aluminum, drilled); control pedals, footpegs and hangers (aluminum, relieved and drilled to reduce weight even further); swing arm (a combination of 6061 round aluminum tubing and plate with eccentric chain adjusters, designed by Kawasaki’s Randy Hall and built in several lengths to suit different tracks, those lengths again determined by testing in 1980); and steering damper (externally adjustable, made of steel a decade ago and due for an aluminum replacement in time for the 1 982 season).

There are parts which didn't come out of Kawasaki's California machine shop, notably the front brake calipers. Monsterous one-piece hunks of magnesium, each caliper carries four live pistons, two on each side, pushing two long pads. (The factory sent pads in two compounds, soft and hard. Muzzy’s never tried the hard pads, reporting that the soft pads last several Superbike races and that one set finished the AEM Riverside Six Hour, which Lawson and co-rider Ron Pierce won). Fluid gets from one side of the caliper to the other through an external line. Originally built in the KH1 race shop in Japan, for use on the KR500 Grand Prix racebikes, these calipers proved to be too powerful for such a light bike. Installed on a superbike, they are still incredibly powerful, but stopping the extra weight of the big four stroke, perhaps not too powerful, and they never fade. The rear disc, 229mm, came from a water-cooled K.R750 Triple, and was made in the factory’s Japanese race shop.

Then there are parts that didn’t even come out of any machine shop, being offthe-shelf production items like the Lockheed rear brake caliper and the stock KZ1000J fork sliders, speedometer and gas tank. True, the guts have been ripped out of the speedo and the needle modified to appear bent by violent collision with the 85-mph limiter peg on its face. True, also, the once-stock KZ1000 seat has been shaped to lower the rider and offer support against strong acceleration, and now has the remnants of a stock tail section, taillight and rear fender permanently attached to it, the unit as a whole secured to the motorcycle with Dzus fasteners.

The wheels are Morris magnesium, WM4-1 8 in front and WM8-1 8 in the rear. The aluminum oil cooler came from Earl’s Supply in Los Angeles and lasted through every 1981 race except the first Daytona, at which another brand of aluminum cooler sprung a leak and prompted the switch. The shock absorbers sit at about the same angle as a stocker, and are made by Works Performance for use on Maico motocrossers. Called Maico Magnum Crossers by Works Performance founder and designer Gil Vaillancourt, the shocks have damping modifications to accommodate paved tracks without jumps punctuating each straightaway, and are equipped with tw'o-stage springs instead of the three-stage springs used on dirt models. Muzzy selected the Works Performance shocks because he was familiar with them from his dirt track race efforts, and because the damping can be adjusted at the track. “Changing to the Works Performance shocks gave us the ability to change the damping in the field as we saw fit,” Muzzy says, “So at least we had control. We weren’t handicapped by just having, let’s say, four sets of shocks with different settings in them. We can take what we have and change it in any direction in the truck, at the time.” * * *

Lawson has suited up and the photographers are out on the track, in position. Muzzy squirts raw gas from a plastic squeeze bottle down the throat of each carburetor, then, with the help of the mechanic, push-starts the bike. The engine comes to life sounding raspy and rough. Patiently, Muzzy stands next to the bike. warming it up, feeling the oil cooler for any sign of warmth.

It takes several minutes in the pits before the Kawasaki sounds crisp. Lawson climbs on and heads out onto the track.

“Erom a privateer level a guy would be crazy not to race one of these, considering what it takes to make a Suzuki, or Honda run,” Muzzy says, watching Lawson circulate on the race course slowly, warming up himself, and the tires. “There isn’t a thing in this bike I couldn't duplicate myself out of my shop at home. Transmission gears are no problem for a serious privateer. I had North Side Gear in the (San Lrancisco) Bay area make up some gears for my dirt tracker. It cost something like $700 for four gears, and they’ll make anything you want.”

Lawson is riding faster now, his shifts so quick and sure that it sounds as if the Kawasaki is equipped with an air shifter. Lawson doesn’t use the clutch to upshift, instead cracking the throttle back a tiny, instantaneous bit and pulling up on the shift lever sharply. It’s faster that way, and done correctly, as positive as shifting with the clutch.

I ask Muzzy what the wheelbase is, and he tells me it measures 59 in. with the 19in. swing arm now in place, and the bike as it sits now is how Lawson rode it at Daytona two weeks earlier. I wonder about rake and trail, and Muzzy replies that he doesn’t know, that he'd have to measure since both figures vary according to location of the rear axle and the position (height) of the fork legs in the triple clamps.

“As with everything in racing, it's the combination that counts,” says Muzzy as Lawson sails past again.

Lawson pulls into the pits. It's my turn to ride. I pull on my helmet, climb on the bike, and let out the clutch as Muzzy and the mechanic push, then I'm on the track and accelerating for the first turn.

Seat-of-the-pants it’s hard to compare two big racebikes unless they’re both at the same track at the same time, but so far there aren't any surprises. Lawson’s Kawasaki doesn't accelerate noticeable harder than my bike, and it . . . DLLINITELY STOPS HARDER! I’ve heard about good brakes before, and thought that my bike's combination of 330mm cast-iron discs and Lockheed calipers was good, but not like this! This is more like braking power too strong to imagine, but then, that’s what it would take to allow' Law'son to make some of the turns I’ve seen him make despite not putting on the brakes until obviously too late". Too’ late only applies to conventional stopping information, not the brakes on this bike.

DRAGSTRIP DISASTER, OR WHY WE DIDN'T TEST THE BRAKES

Kawasaki Race Manager Gary Mathers was against the idea from the beginning. “It’s not a drag racer,” he said.

“Yeah, but the readers expect it,” I countered.

My argument prevailed and so it was that Rob Muzzy and I took to the dragstrip with Eddie Lawson’s Kawasaki. The first few passes were slow—too slow—-the bike turning 10.80s at 131, and Muzzy re-geared. One tooth each way didn't change much, although a better launch and Muzzy telling me to shift at 11,000 instead of the usual 10,000 rpm did bring E.T. down to 10.63 at 132.15 mph.

A good run was hard to make, the bike standing on its rear wheel at the top of first gear, but the slow terminal indicated that something was wrong. When we tested Wes Cooley’s Yoshimura Superbike in 1979 it ran 10.66 at 132.74 mph, and that was two racing seasons ago. The engine in Lawson’s bike—a veteran of the final event at Daytona and our Willow practice session—was obviously tired.

“Let’s make one more pass before the brake tests,” I suggested.

About 25 ft. before the first E.T. light, at 10,800 rpm in fifth, the vibration started. Before the lights I had the clutch in but it was too late. The number three connecting rod had broken and smashed through the cases, filling my right boot with oil and flakes of aluminum.

So much for the dragstrip.

John Ulrich

Good brakes or no good brakes, there’s something wrong as I put the bike into the wide-radius, long Turn 2. I’m still trying to sort out what I felt when I reach bumpy, sweeping Turn 8. The bike snakes toward the edge of the course, the w'obble taking me by surprise and setting me back. It’s hard to ride fast when a bike is doing its best to instill religious fervor into the rider, and I’m definitely not riding fast. Several laps later the handling hasn’t improved and I’m turning l:4l laps, no faster than I’ve gone on my Stock Production-class GPz550 with street tires.

It’s easy to think that all factory riders have to do is go out and ride around on magic bikes and they’ll turn record laps and win big over the budget-constrained privateers. And all the times that I sat in £he pits at races, befuddled by an ill-handling motorcycle and confused by the tryit-and-let’s-see changes in spring rates, fork height and shock damping proposed by my riding partner and assorted friends, it was easy for me to imagine that the factory guys simply consulted their big, thick face diaries and dialed in the appropriate settings for track conditions, no trouble.

But this magic championship Kawasaki isn’t working like anything worth having and I’m not interested in riding it anymore, so I pull into the pits and ask Lawson what he thinks.

“Knowing how' to dial in the bike and get it going straight all the time is the hard part,” Lawson tells me. “Superbikes are easier to ride than a 250 because they’re big and heavy and the pow'erband is so much smoother and easier to get used to. But it’s hard getting the wobble out of them. Once you get the wobble out of them they’re easy to ride.

“If we were racing here I’d probably go through a lot of shocks and springs and damping,” Lawson continues. “I don’t have all the answers. Sometimes I don’t know. A lot of times it’s trial and error. When I don’t have a clue I ask Rob.”

“The problems you have are generally related to lap times,” adds Muzzy. “At certain lap times things are okay. Early practice may be okay. But then Eddie will turn 3.0 sec. a lap faster in Saturday practice and all the sudden you get all sorts of problems, as you put more stress into the bike. It’s unbelieveable what they’re doing with a street bike, which is what this really is.”

“Sometimes we change springs, spring rates, trying to get it to be more progressive at the end, at the bottom,” continues Lawson. “We change air pressure, a little less, a little more. Sometimes we take the damping rods out and change those, make the holes a little smaller; change the oil, little heavier oil, little lighter oil. Just a lot of involved things. It gets pretty complicated sometimes.”

I ask Lawson what was the shortest amount of time it ever took him to get his bike set up for a Superbike race.

“At Loudon,” he answers, instantly. “In about half a day we got it pretty close.” What about engine tuning?

“I do plug chops,” Lawson says, “and Rob takes care of all the rest. He looks at the plugs and tells me if it’s rich or lean. These things are so hard to tell. You can go out there and say it’s fat on the bottom or whatever, but he gets it dialed in for the top end. Sometimes I’ll try different motors. I might say that this motor is a little stronger here in this range than that motor. Or we might try different pipes, maybe this pipe works better down low or this pipe works better up top. You might change the timing or something and go out and try it. But we need set-up time at every track. A lot of times we try stuff just to try it, to see what it will do.”

The biggest problem I’ve ever tackled on a racebike is chatter, and I ask Lawson how he deals with it.

“Sometimes it comes from the back end, making the front end chatter,” Lawson says, complicating the question. “Sometimes it comes from the tire, too.”

“How can a rider tell?” I ask.

“Change it,” Lawson replies. “Try it. I’d work on the suspension first. It depends .pon what kind of chatter it is. Sometimes it’s hopping or it’s just a real light chatter. If it’s a light chatter you might want to try different fork pressure. If you change everything in the front end and it stays right there I go to the back end.

“We keep notes. A lot of times I don’t know what to do and I just ask Rob or Steve (Johnson, who built Lawson’s 250cc championship-winning KR250 and who sometimes assists with the Superbike). I'll ask them what they think. I’ll say what it’s doing and they’ll look back in the notes and see how we had this problem at this racetrack before, and what fixed it. A lot of times 1 get saved by these guys knowing what to do.

“I pick all my own tires, though,” Lawson says. “That’s one thing I have a pretty good feel for. I know what’s going on, tire wise. We try a lot of different tires in the practices and we know what it’s going to do. We look at the profile of the tire and we look at the wear and just by the seat of my pants I can tell you if it’s hooking up better or not. Sometimes it hooks up well with a certain tire but you can tell that it’s not going to make it (the distance of the race), so we have to go with a harder tire. None of this last-second-guessing. We pretty much know what it’s gonna do.”

The wind is howling now, blowing dust and tumbleweeds across the pavement, and the photographers want more pictures, this time wheelies. Lawson heads out onto the track and lofts the front wheel, carrying it far down the straight in a crooked path, leaning this way and swerving that way as gusts blow against him.

The weather is worsening, the sun getting lower in the sky, and it’s too late for Muzzy and crew to work on suspension, too late for me to try the bike again, set up better for Willow.

All I can do is watch Eddie Lawson wheelie down the straightaway, past the photographers, toward the first turn, time after time.

The thing is, standing at the pit wall looking at the mega-buck factory-backed teams, watching Lawson streak to win after win, it’s easy to assume that if you or 1 had Lawson’s wonderful bike, we’d be out there winning Superbike races too.

It isn’t that way. 1 rode Lawson’s bike set up just as it came from his third place, championship-winning finish at Daytona. But 1 rode it at Willow and it didn’t work at all.

Without the ability and patience and knowledge to tune the bike to each and every track, Lawson's Kawasaki is worthless.

And that is the biggest secret of all. IS*

SPECIFICATIONS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

FEBRUARY 1982 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

FEBRUARY 1982 -

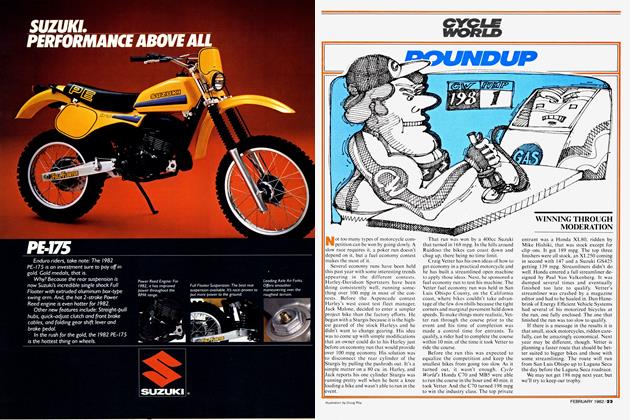

Cycle World

Cycle WorldRoundup

FEBRUARY 1982 -

Competition

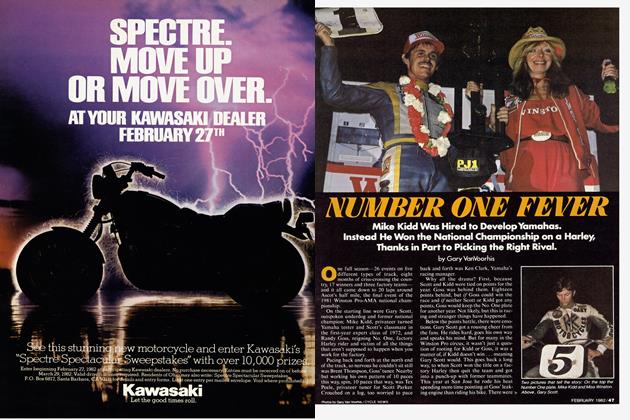

CompetitionNumber One Fever

FEBRUARY 1982 By Gary Vanvoorhis -

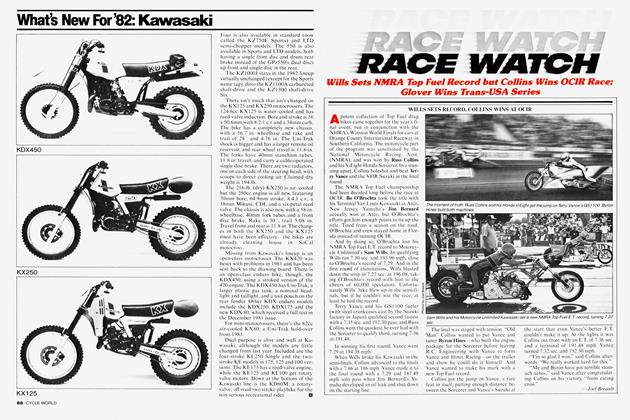

Race Watch

Race WatchWills Sets Record, Collins Wins At Ocir

FEBRUARY 1982 By Joel Breault -

Race Watch

Race WatchGlover Tops Trans-Usa

FEBRUARY 1982 By Tom Mueller