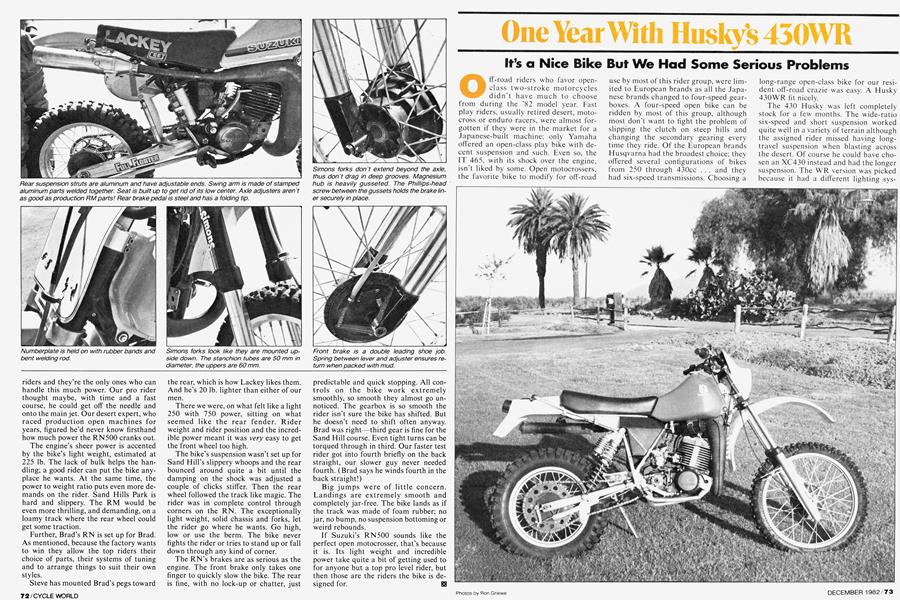

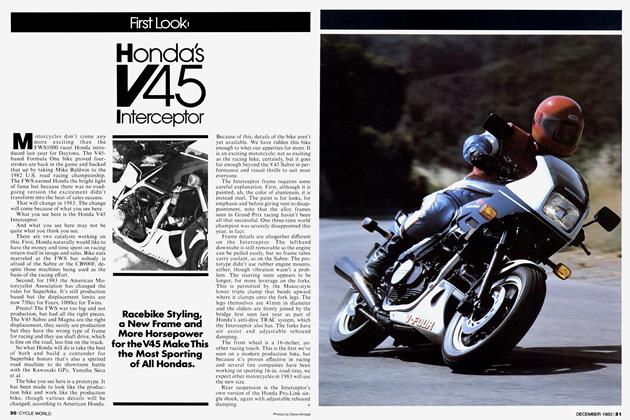

One Year With Husky's 430WR

It’s a Nice Bike But We Had Some Serious Problems

Off-road riders who favor openclass two-stroke motorcycles didn't have much to choose from during the '82 model year. Fast play riders, usually retired desert, motocross or enduro racers, were almost forgotten if they were in the market for a Japanese-built machine; only Yamaha offered an open-class play bike with decent suspension and such. Even so, the IT 465, with its shock over the engine, isn’t liked by some. Open motocrossers, the favorite bike to modify for off-road

use by most of this rider group, were limited to European brands as all the Japanese brands changed to four-speed gearboxes. A four-speed open bike can be ridden by most of this group, although most don’t want to fight the problem of slipping the clutch on steep hills and changing the secondary gearing every time they ride. Of the European brands Husqvarna had the broadest choice; they offered several configurations of bikes from 250 through 430cc . . . and they had six-speed transmissions. Choosing a

long-range open-class bike for our resident off-road crazie was easy. A Husky 430WR fit nicely.

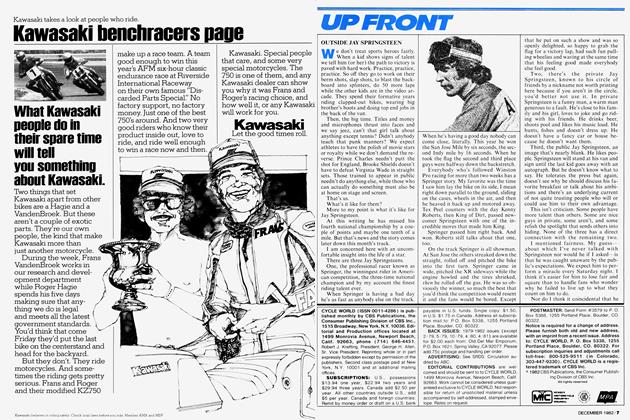

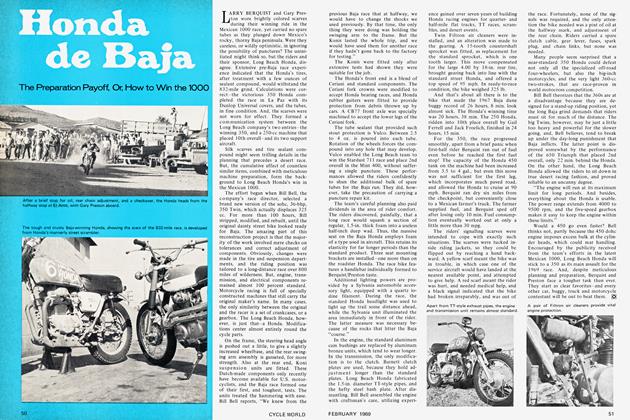

The 430 Husky was left completely stock for a few months. The wide-ratio six-speed and short suspension worked quite well in a variety of terrain although the assigned rider missed having longtravel suspension when blasting across the desert. Of course he could have chosen an XC430 instead and had the longer suspension. The WR version was picked because it had a different lighting system the WR's system put out 130 watts and the bike could easily be fitted with a lOOw Baja light. So, the first project was to change the suspension. We gave Husky a call and they sent parts to convert the WR. The parts consist of longer fork damper rods (the stanchion tubes, springs and sliders are the same), a longer swing arm, chain tensioner, new shock springs, new shock damping washers (the shocks are basically the same between the models, the WR has a travel limiter to shorten the travel), a new brake rod and instructions for working on the shocks. The better part of a Saturday was needed to convert the WR suspension to the XC specs. Japanese oil seals were used in place of the stock Husky seals which never leaked badly but never completely sealed either. Only one new seal was used in each slider, although Husky’s come with two seals in each slider. One Japanese seal cuts the friction and completely stops the drool. Fifteen oz. of lOw Spectro fork oil completed the fork work. The shocks were taken to a local Husky shop for conversion. Ohlins shocks have three internal snap rings and it’s impossible to work on them without the proper tools and experience.

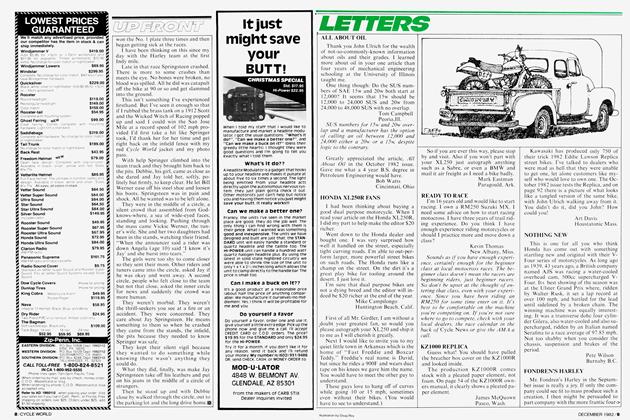

After having Yamahas and Suzukis and Hondas for long-range bikes, the Husky proved thrilling to stop from high speeds; after overshooting too many turns we lengthened both of the backing plate arms for better leverage. About a half an inch was welded to the center of each arm. It helped some but the brakes simply aren’t strong enough for high speed use. And they seemed to lose effectiveness with each brake lining change. The brake linings wear rapidly too, needing replacement as often as 500 mi. About 400 mi. into the test the front brake started to feel as if it was on all the time. The front wheel was removed and inspected; the steel brake drum had come loose from the hub and moved outward. The damage was severe; the backing plate, brake shoes and hub had to be replaced. Husky has a short warranty period but an occasional rider probably wouldn’t have had the problem before the warranty was over. Husky spokesmen said they would have covered the problem anyway.

At about 500 mi. the exhaust pipe developed a stress crack in the bottom of the center cone, just above the head. We’ve seen many others do the same. The metal is very thin at this point. We welded the crack and formed a piece of thin gauge sheet steel over the area, welded around its circumference and had no more problems until the bike had covered 2400 mi. Then the pipe’s stinger broke in half just behind the center mount. It, too, was welded back together. The front support bracket was a problem from time to time also. The pipe apparently sunk as the mounting strap would start to make contact with one of the fins on the head from time to time. We finally cured the problem by grinding off part of the bracket so it had more clearance.

The silencer was a problem area from day one. There’s a small screen in the spark arrester that clogs quickly and kills top-end power. We removed it and tossed it into the trash can. Then the large cone in front of it started clogging every 300 to 400 mi. After taking the cone out and spending an hour poking the carbon out of the tiny holes, while sitting on a berm deep in Baja, we enlarged most of the holes with an electric drill. That ended the constant problems with the damn thing.

The 430 exhibited other minor but irritating traits before the 500 mi. mark; oil started leaking from around the shift lever shaft, the bottom roller on the chain guide seemed to wear out every other ride or so, the clutch cable needed replacement almost as often and the jetting requirements began changing every ride. The chain roller problem was fixed by using a Malcolm Smith roller that featured steel roller bearings. Terry Cable clutch cables were tried in place of the Stockers, but they didn’t last much longer. The ever changing carb jetting turned out to be caused by a defective wet-side crankshaft seal. The had seal would suck transmission oil from the transmission, causing an over-rich mixture. Leaning the jetting would be effective until the transmission oil level dropped below the seal, then the bike would be too lean. Then we would change transmission oil and the cycle would start all over again. Drove us nuts until we figured it out. Changing the seal, a simple job on most modern twostrokes, is needlessly complicated. The Husky’s wet-side seal faces the crank which means the engine has to be completely disassembled to change it. Once

inside the engine, we found a small gear was discolored due to lack of oil from running the transmission oil low. The gear and the crank seal were replaced and the engine went back together, never to give trouble again. The shift shaft was removed several times in an attempt at stopping the oil leak. After several tries it still leaks oil. The problem is something that shouldn’t exist on a modern bike. The shaft has a wide square cut in it but the factory only uses one small o-ring in the cut. Oil easily runs around it. We tried using extra o-rings but the bike still leaks oil onto the garage floor between rides.

The forks seemed to have more than their share of problems also. Husqvarna uses a plastic disc that traps oil for a topout device. Everyone else uses a short piece of wound wire spring. Springs seldom if ever go bad or cause trouble. Husky’s disc needs replacement every 800 to 900 mi. or the forks top out and jar the rider’s arms badly. We ran lOw fork oil the whole time instead of the recommended 15w and that may have had something to do with the short disc life, but still . . . what’s wrong with a short spring? We evidently weren’t the only ones with the problem as our local dealer was almost always out of them, requiring a wait of one month the last time they were changed.

The steering head bearings needed replacement about the 2000 mi. mark. We hadn’t greased them throughout the test and the bars started turning with difficulty from straight ahead. Disassembly showed the bearings and races were ruined. The bearings are of a high quality but the seals didn’t do their part. This is the first long-range test bike during the last five years to need steering head bearing replacement. Grease them often if you don’t want to buy bearings.

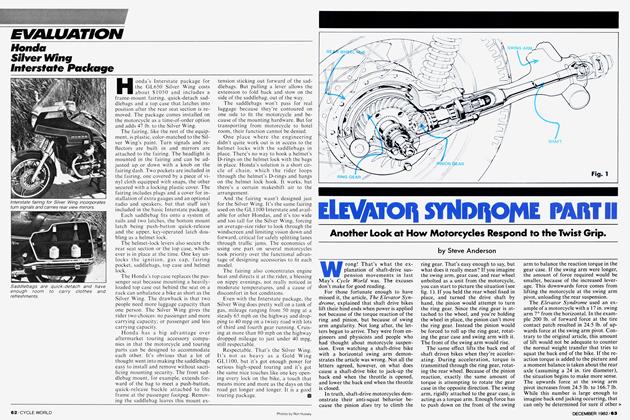

Modifications to the bike were minor excepting the suspension changes. The gas tank was replaced with a plastic one from Malcolm Smith. The Smith tank holds a full 4 gal. and fits the bike perfectly, is narrow at the back and wide at the front. It comes with easy to understand instructions, all the needed mounting hardware, a petcock and a nice aluminum gas cap with external vent hose. The extra capacity makes long off-road rides carefree by extending distances between fuel stops to around 100 mi.

The rear shocks were changed about halfway through the test period, not because we were unhappy with the Ohlins, but because Works Performance sent us a set of their latest motocross models called Magna Crossers. They are beautiful shocks with finned reservoirs, triplerate springs and heim-joint eyes. But probably the best part is they weigh about 3 lb. less than the regular Works shocks and they are nearly that much lighter than the Ohlins. Anyway, they work great, maybe being a little plusher through the small bumps and never bottoming through the giant ones. They are a good choice if you're in the market for lightweight shocks.

Other small mods consisted of trimming the bar width about an inch, adding a buffer block to keep the chain away from the rear tire (one from a Honda CR480 was adapted), Malcolm Smith grips, a boost bottle and magnifying lens for the odometer. The boost bottle was added to increase the torque. It proved quite difficult to install. A small aluminum pipe was shaped just right, the reed manifold between the reed and carb was ¿drilled, the pieces fit, and the parts were taken to a local shop for heli-arc welding .. . but they couldn’t weld them! The manifold was magnesium, the pipe aluminum, not compatible. Damn. Four Minute epoxy, available from almost any hardware store, came to the rescue. It bonded the parts together in four minutes as the instructions promised and they have stayed bonded for over 2000 mi. without sign of cracking or stress. The bracket for the bottle (the bracket, hose, bottle and other bits and pieces are stock Yamaha parts) was bolted to the bottom of the plastic tank. Bolts with large rubber washers on the inside prevented leakage.

The stock rear fender survived the entire test period with no problem. The taillight lens fell off once but the replacement hasn’t. The front fender was replaced with Gold Belt's new DeFender. It’s longer, wider and better. It features a floppy front that bounces off mud before it can build up too heavily and a small bridge on its underside, just before the tip, diverts water down so it can't be blown around the front and into the rider’s face. Additionally, the back part has cast-in vent areas that can be easily opened up to let air to the engine if the bike is used in desert terrain.

Since the WR was designed as an offroad machine but didn’t come with an add-on skid plate, we decided to test the bike as it came. An additional frame tube runs through the center of the frame's lower part to help protect the engine’s center cases but that’s all. The cases endured the test as did the clutchside cover. The plastic mag cover didn’t. It got smacked against a rock in Baja and developed a huge crack but didn’t fall off. Some silicone seal (what did we do without it?) made a quick repair. In fact, we didn’t bother replacing it for a couple of months!

Another small but neat modification concerned the VDO speedo/odometer. The numerals are small and hard to read while bouncing along at speed during an enduro. The problem was solved by removing the magnifying lens from a defunct IT odometer and siliconing it over the odometer. The cheap and easy fix works.

We used lots of tires during this test. A Metzeier 150/80 four-ply was usually the choice at the rear. Dunlop K190s were used at the front. The rear Metzeler is a very wide tire in its 17-in. form and the buffering mentioned earlier was needed to keep the chain from sawing off the side knobs. Rear tires usually lasted around 500 to 600 mi., fronts about twice that long. Cheng Shin heavy-duty red inner tubes were used.

After the stock chain went south a Malcolm Smith O-ring chain was installed. They are excellent chains that last at least twice as long as regular chains and don’t require lubrication. Sure is nice on long loops through Baja. An 11-tooth front sprocket was used

with a stock 53-tooth rear. The smaller front closes up the jump between the wide ratio box but has a very short life span as it turns fast. Normally the front sprocket was changed twice to every chain, around 600 mi.

Many parts on the Husky proved durable and long lasting. Many proved short-lived and a pain. Maintenance between rides was needed more often than on previous long-range test bikes. The stock air cleaner is still in the bike and going strong, the original bars are in use, no broken spokes, no frame breakage, stock seat and cover are in good shape, original speedo cable and VDO still working fine, stock reeds working, original rims are still round. The short lived parts have been explained. The maintenance is hard to describe. Seems the bike always needed a Saturday’s worth of little things; the spark arrester cleaned, silencer packed, air cleaner cleaned, pipe brackets adjusted, clutch cable changed, brake shoes changed, chain rub block at the front of the swing arm changed . . . something. Some parts on the bike gave poor service life also; the footpeg pivot bolts have elongated the mounting holes in the frame, the brake rod has elongated the brake pedal where it connects, both front and rear brake stay arms have bent at least twice, and the pipe we mentioned earlier is ready for the trash can.

This bike was used hard and many of its miles were in Baja, the Mojave Desert, local mountains and places in between. It also competed in the Tecate 500 enduro where it crossed waist-deep creeks without a whimper. We like the bike but at the same time, we’re concerned about the problems we’ve had and the ever-constant maintenance it requires. These bikes cost a lot of money and they shouldn’t have some of the problems they have. BE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue