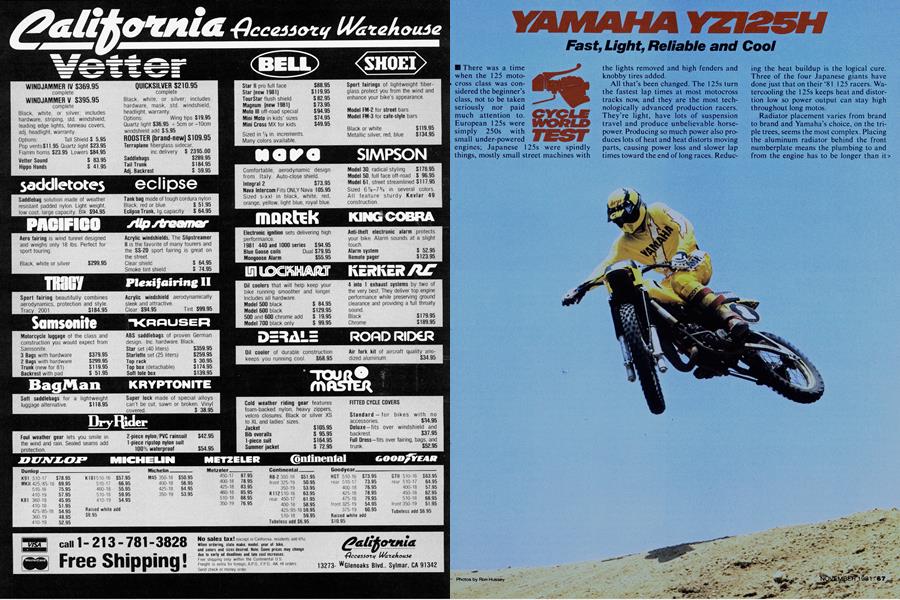

YAMAHA YZ125H

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Fast, Light, Reliable and Cool

There was a time when the 125 motocross class was considered the beginner’s class, not to be taken seriously nor paid much attention to. European 125s were simply 250s with small under-powered

engines; Japanese 125s were spindly things, mostly small street machines with the lights removed and high fenders and knobby tires added.

All that’s been changed. The 125s turn the fastest lap times at most motocross tracks now, and they are the most technologically advanced production racers. They’re light, have lots of suspension travel and produce unbelievable horsepower. Producing so much power also produces lots of heat and heat distorts moving parts, causing power loss and slower lap times toward the end of long races. Reducing the heat buildup is the logical cure. Three of the four Japanese giants have done just that on their ‘81 125 racers. Watercooling the 125s keeps heat and distortion low so power output can stay high throughout long motos.

Radiator placement varies from brand to brand and Yamaha’s choice, on the triple trees, seems the most complex. Placing the aluminum radiator behind the front numberplate means the plumbing to and from the engine has to be longer than it> would if placed on the frame downtube, and innovative engineering is needed so the hoses don’t kink or bind.

Yamaha overcame these obstacles by using frame tubes, the steering stem and triple trees to route the water. The water leaves the bottom of the radiator through an elbow and short piece of rubber hose, into the hollow lower triple clamp, then into the lower part of the steering stem, out a hole in the side of the stem, into the frame’s steering head pipe, then into the downtube. The bottom of the downtube is capped and fitted with a hose outlet so the water can be routed externally via another rubber hose to the primary driven pump. Water exits the pump through an external steel tube and enters the left side of the cylinder’s water jacket, swirls around the cylinder and the head, then exits the top through yet another external rubber hose that guides the water up behind the downtube to the top right side of the steering head pipe. The heated water entersYhe frame and steering stem but doesn’t mix with the cooler water, thanks to internal dams built into the center of the stem and steering pipe. From the stem it goes into the hollow top triple clamp and back to the radiator through another short piece of external rubber hose. Rubber O-rings keep water from leaking around the triple trees and grease seals keep it away from the bearings and races.

In the interest of lightness the radiator core is fairly small, measuring 6.3 x 3.9 x 1.25 in. Water volume is less than a quart but the small pump, turning at approximately two-thirds engine crankshaft speed, cycles the water every three seconds at maximum engine revs.

Except for the water cooling, the 125 engine is fairly normal stuff. A six-petal reed is placed between a 34mm Mikuni carburetor and the piston, the clutch is a multi-plate wet unit that doesn’t slip, the transmission is a six-speed, primary drive is handled by helical gears and primary kick starting is standard. The engine bolts to the frame in three places; the lower front, under the middle and at the rear. The front and bottom are normal 8mm bolts, the rear utilizes the large swing arm bolt. No head stay is used.

All frame tubes are chrome-moly steel. Construction is typically Japanese, good design with strong but sloppy looking welds. The frame design looks different, even for a monoshock. The backbone tube takes a sharp dive from the steering head then curls back slightly before ending just above the engine. Four smaller tubes sprout from the area around the main tube’s end; the top two become supports for the seat, the lower two drop at a steep angle to provide a mount for the swing arm bolt, then roll forward under the engine and end at the front downtube above the engine’s exhaust port. Gusseting is plentiful and distinctive, especially around the steering head.

The strangely shaped backbone tube keeps the weight of the steel frame tubes low and makes a place for the aluminum bodied shock to mount ... on top of the backbone tube. The shock is regular ‘81 Yamaha trickery; rebound damping is readily adjustable to any of 24 positions by hand and spring preload is only slightly more difficult but requires the use of the supplied 32mm wrench. A large capacity aluminum reservoir is mounted on the left side of the frame downtube and does away with heat produced hydraulic fade for all but factory level racers. A single shock spring is used and it’s the right rate for riders weighing 140-150 lb. Yamaha has optional springs, stiffer or softer, for those riders who aren’t in that weight range or think they want a different rate spring. The YZ is very sensitive to rider weight and spring rate.

An aluminum swing arm helps reduce the weight of the YZ. It’s made of square stock, has good triangulation and strength, and pivots in needle bearings.

Front suspension is nicely handled by KYB forks with 38mm stanchion tubes. Wheel travel is 11.8 inches, same as the rear. Both wheel assemblies have strong spokes, good hubs and aluminum rims. Both have the same size brake drums and single leading shoe backing plates. No complaint here. The light weight of the bike and generous size of the drums combine to give quick, controlable stops.

Building an airbox around the monoshock has always been an engineeringproblem. Past units have usually had filters squeezed into tight boxes that made cleaning difficult.

The H is no different. The two-stage foam filter cleans handily but maintenance is grim. The cone shaped filter fits over a cone shaped plastic cage and the unit packs tightly into the airbox with little room left over to check the edges for complete sealing. Even so, the biggest hassle is the nylon nut that secures the unit to the airbox. The nut has small raised pegs that are supposed to provide enough grip for oily fingers to turn . . . and there’s damn little room for adult sized fingers. At least the unit is easy to get to; the inspection cover is held in place by a steel wingnut and comes off without removing the seat or side number plates.

Bits and pieces on the YZ125H are first rate; the throttle is a straight-pull job, hand levers are dog-legged and the pivots have split clamps so replacement is simple. Grips are usable, bars are shaped right, the shift lever folds, control cables are nylon lined and have heavy outer casings, cable guides are among the best on any bike, the chain guide and rub blocks are quiet and long wearing, the seat is thick and comfortable, plastic parts are good looking and well made, and the tires are fine for most riders.

Like most 125s, the little YZ is a breeze to start. It usually takes several prods when cold but kicking the small piston through is easy. Once running, don’t get in any hurry; watercooled bikes take 3 or 4 min. to warm-up. Take the time to do it so internal parts can expand to proper working clearances before being loaded. Otherwise, engine parts will wear rapidly.

The YZ is as agile as it looks. The bike’s light weight and super responsive engine let the H dart in and out of corners. Power output is strong but contained in a narrow band toward the top of the rev range. Going fast means constant shifting and clutch fanning while the throttle is held full on. Normal corners require at least one down shift, tight corners require two or three to keep the engine on the pipe and pulling strongly. If in doubt, downshift.

An engine as highly tuned as the 125 YZ needs a smooth shifting transmission with many gear choices. The YZ is so equipped. Six speeds offer perfect internal ratios so the rider doesn’t have any jumps or lags in the ratios. Lightweight riders can use 2nd gear for motocross STARTS,H heavier racers will have to use 1 st and shift to 2nd as soon as the bike clears the starting gate. Past shifting is accomplished by holding the throttle open, loading the shift lever with your foot and just touching the clutch when you want the shift made. With practice it can be done quickly and ^ smoothly.

A 209 lb. bike with nearly 12 in. of travel at each end should go through the bumps and rough stuff well. The YZ125 does. If the suspension is set up for the rider who’s aboard, the bike will go through whoops at an extremely fast pace. Setting it up for the rider’s weight and ability is the secret. Small changes make, large differences in the way the YZ handles. Best to take time to dial it in or the guy on that stock RM125X will eat you alive. Even dialed, the RMX racer will have an advantage—the RM engine has more mid-range power which makes it easier to ride, and the RM’s suspension fits a broader range of rider styles and weights without tuning.

Looking at the spec chart reveals a strange weight bias of almost 50-50. Most dirt bikes have somewhere around 46 to 48 percent of the weight on the front wheel. Even so, it isn’t noticed when riding. There’s no tendency to dive over jumps and the front is easy enough to loft if needed. The heavier front actually makes the bike better in slippery off-camber turns—the rider doesn’t have to shift as much of his weight to load the front tire to keep it from sliding out.

The seemingly unnecessary complexity of the YZ’s watercooling had us worried about reliability when we first received the H. Thus we decided to keep the bike around, trail ride and race it for at least three months before writing this test.

The little waterpumper surprised us by being one of the most reliable 125 motocrossers we’ve tried. The spokes needed tightening often but otherwise the bike hasn’t given any problem. The head hasn’t even been off! No rings, pistons or other internal parts have needed replacement, almost an unbelievable record for a normally high maintenance size racer. Even the cooling system has shown remarkable longevity—it’s needed water a few times, not much, but no external leakage has been noticed. Maybe it seeps internally, but it’s not bad enough to bother with.

YAMAHA

YZ125H

$1499

SPECIFICATIONS

We raced the YZ in the novice, intermediate and pro classes at local motocrosses and the novice and intermediate classes at local TTs and half miles. The little motocrosser blew the minds of the track guys, racing with knobby tires and 12 in. of suspension—not normally the hot set up for track bikes. The bike proved a winner on the smooth tracks as well as rough MX courses.

If you hadn’t guessed by now, we liked the little YZ125H. Set up right, it’s a competitive racer or play bike that’s light, fast, well-built, available and reliable. ES

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

November 1981 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1981 -

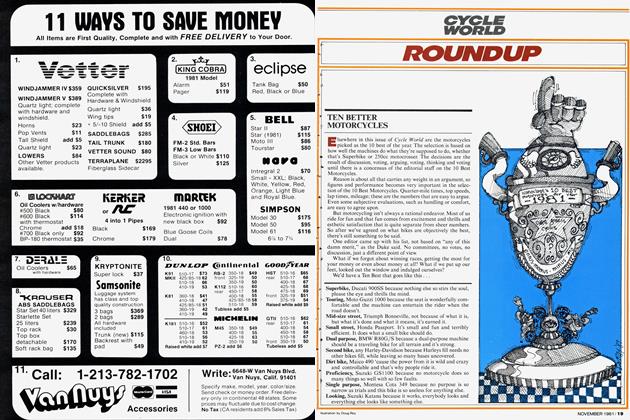

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

November 1981 -

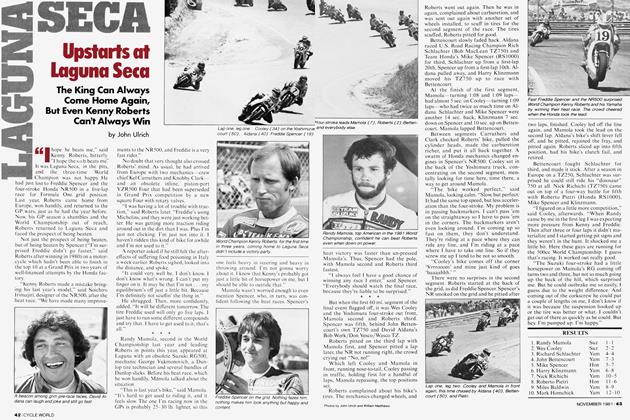

Laguna Seca

Laguna SecaUpstarts At Laguna Seca

November 1981 By John Ulrich -

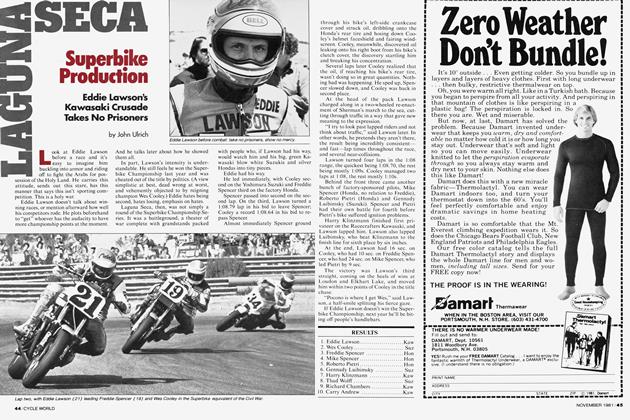

Superbike Production

November 1981 By John Ulrich -

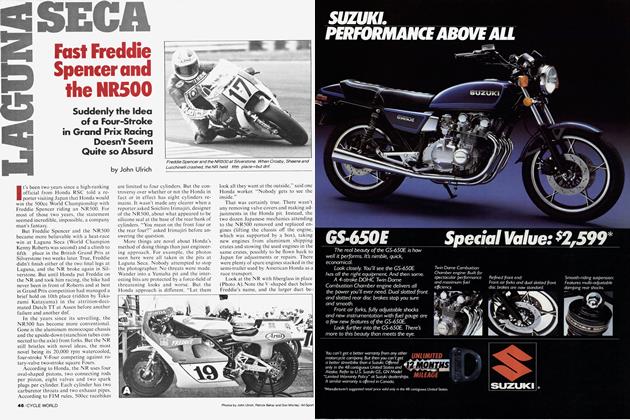

Fast Freddie Spencer And the Nr500

November 1981 By John Ulrich