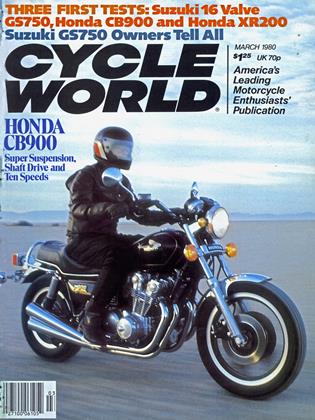

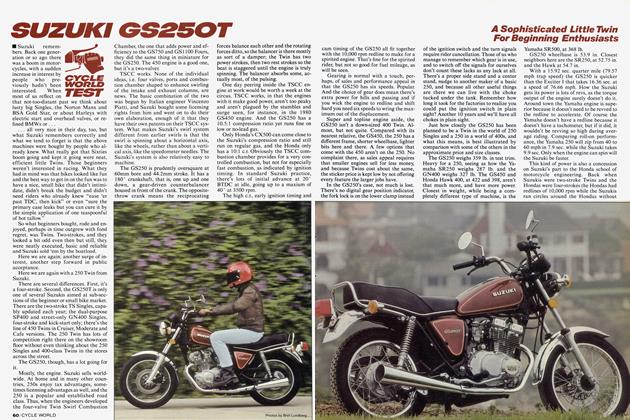

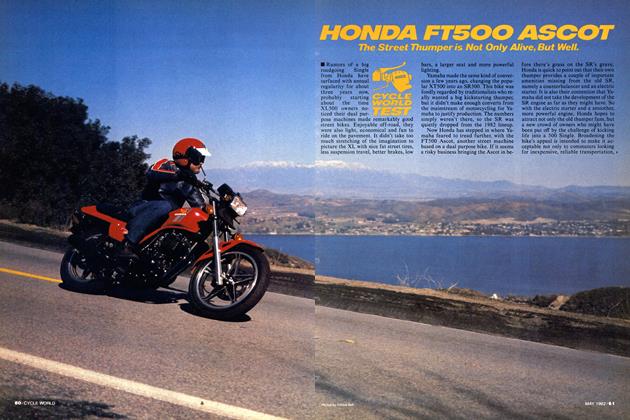

HONDA CB900

CYCLE WORLD TEST

A Science Fiction Motorcycle: Air Suspension, Two Transmissions, Shaft Drive Drive and More.

Compromise isn't exactly the right word for the new Honda CB900 Custom, but it's a word that comes to mind. Usually Honda goes its own way, building what it feels are excellent motorcyles and finding that the market usually follows where Honda leads. Except that Honda didn't lead the market with custom styling and

even though Honda was an early entrant in the shaft drive arena, it wasn’t the first company to offer a shaft drive motorcycle in the medium displacement class from 750 to 900cc.

That’s where the CB900 Custom comes in. It is all the motorcycles that Honda hasn’t made. It’s also not a totally fresh design; it borrows heavily from other existing Hondas and because of that it has some highly unusual features.

The CB900 story begins at the dealer showrooms where customers wanted to see> what Honda had to compete with the

Yamaha XS750 and the Suzuki GS850. A

shaft drive version of the new CB750K is

what the dealers had in mind. And while

Honda could certainlv have stuck a shaft •/

on the 750, the engineers knew' that a shaft would add two bevel gears that would waste horsepower and the whole affair would add weight, resulting in a noticeably slower motorcycle than the existing 750. That, the engineers decided, was unacceptable. The solution was simple enough: use the 900cc pieces from the European CB900F.

Basically, the CB750 and CB900 share the same engine. It’s a dual overhead cam, 16-valve, air cooled, inline Four. The crank runs in plain bearings and drives the transmission through a Hy-Vo type chain. But there are subtle differences between the crankcases of the two motors that are only apparent when they are sitting side by side. It’s true the crankshafts are interchangeable, but the 900 uses a 1:1 ratio on the primary chain while the 750 is geared down. That requires a longer primary chain on the 900. The rods are different, and the cylinders are larger and longer on the 900, w hich means different cam chains are necessary. Even the heads are ever-soslightly different, as the 900 uses bigger valves in a combustion chamber that’s a tiny bit bigger.

Ignition for the CB900 is the same magnetically-triggered breakerless affair found on the 750, while the carburetors are slightly larger (32mm vs 30mm) Keihins with accelerator pumps like those of the smaller model. Other pieces, such as the 260 watt alternator and most of the transmission are the same. Because of theiextra torque of the larger motor, however, a couple of the 900’s transmission gears are heat treated for greater strength and first gear is slightly higher, 2.375:1 for the 900 vs 2.533:1 for the 750. And because the 900 engine was made to have an oil cooler attached, the 900 gets the oil cooler, while the 750 doesn’t.

After the power gets to the driven gear on the countershaft of the transmission, it does more than one odd thing. Normal procedure, that is, what Suzuki and Yamaha and Kawasaki do, is to have one bevel gear at the end of the countershaft and another on the shaft and the power flows from the end of the countershaft to the shaft to the final drive ring and pinion on the left side of the motorcycle. This is where part of the compromise begins.

Honda believes shaft drive motorcycles should have engine cranks running parallel to the drive shaft. That’s what the CX500 and GL1000 and new GL1100 have. With that layout Honda positions the driveshaft at the right side of the bike and all of Honda’s equipment for producing shaft drives is so arranged. But the countershaft end on the CB900 is on the left side of the ^aammotorcycle. Honda’s answer is to have another shaft behind the countershaft, this one in a bolt-on housing behind the transmission. That final shaft transfers power from the lefthand side of the CB900 to the righthand side where a bevel gear drives the shaft and all is well. But to connect the countershaft and the connecting shaft Honda uses a straight-cut gear. Actually, four straight-cut gears, as a dog between the drive gears engages one of the two sets, giving a second transmission with two ratios. The subtransmission is shifted with the rocker lever mounted above the normal shift lever. The explanation for the two-speed subtransmission is that it costs very little to add the other gears to the crossover shaft, so why not?

Inside the subtransmission housing is a cam-type shock damper which, in conjunction with the wave washer in the clutch, softens the power delivery of the big Four. The final drive unit on the CB900 is the same one used on the GL1100 and the CX500—same housing and same ratio.

All those transverse shafts on the CB900 make for a long engine/transmission unit. Just how big the mechanicals are becomes clear by looking at the frame. On most motorcycles—and on the CB750—the top frame tubes bend down behind the engine and slope steeply to meet the swing arm pivot. On the CB900 those same frame tubes don!t run straight down, but are angled further to the rear so there is more room for the engine/transmission unit. That makes the distance from the steering

head to the swing arm pivot exceptionally long, but makes the swing arm length very short, 17.5 in. compared to 19 in. on the smaller CX500.

If Honda had wanted, the CB900 could have been made shorter. There are ways, after all, of making motorcycles with less than a 62.2 in. wheelbase. But. This motorcycle is intended to be, among other things, a touring motorcycle. A long wheelbase and long motorcycle gives room for a long saddle with room for two people. A long wheelbase makes a motorcycle stable, even when there’s a Honda fairing on the front and Honda saddlebags aft. Yes, the same Interstate fairing that mounts on the new G L1000 also mounts on the CB900 Custom. Honda made sure of that.

Also helping the CB900 in its role as super tourer is the super suspension. Travel is ordinary, that is 6.3 in. front and 3.9 rear, '“same as the 750. What isn’t ordinary is the air assist, front and rear. Suspension units at both ends aren’t just existing units with air caps bolted on.

Air assist is there because air used as a spring is highly progressive so the more it is compressed, the stiffer it gets. A highly

progressive spring can be soft and comfortable with a light load yet not bottom with a heavy load. Unfortunately, a pure air suspension has a couple of shortcomings. One, when it gets hot during use the air pressure increases and the suspension stiffens. Also, should an air leak develop there will be no suspension and the motorcycle might not be rideable.

Most of the CB900’s suspension comes from the coil springs in the forks and shocks. However the 900 is designed to operate with some air pressure at all times, from 11 to 16 psi in front and from 28 to 64 psi in the shocks. Air volume and pressure in the forks is low enough to have a small effect on ride or handling, though there is some compensation when carrying heavy loads. The shocks, however, are designed for higher pressures and there’s a warning light in the tachometer housing that lights up when shock air pressure drops below 28 psi. Riders are warned to slow down to 50 mph and immediately fill the system if pressure drops below 28 psi. At both ends there are connecting lines so air pressure is equalized and there are half as many fittings to fill. The connecting tube on the forks is relatively short, but the lines for the shocks are longer, joining and ending under the left sidecover on the motorcycle. The long connecting lines for the shocks increase the air volume and thereby increase the amount of suspension from the air volume.

Inside the forks are two springs for variable rate, one stacked on top of the other. Bushings at the end of the stanchion tube and at the top of the slider are made from an alloy Honda says is superior to Teflon. More novelty is packed inside the shocks, though. There are two coil springs, one inside the other, both encased in the shock body. The double springs are necessary because spring length is shorter than usual and to get adequate travel and suspension rate two springs are needed. Unlike conventional shocks, an outer casingextending from the top of the shock down past the lower body, with seals between the casing and the shock body—is used to contain a large quantity of oil. The entire shock body thus cools the oil and the large volume of oil keeps temperatures down which lessens temperature change for the air and keeps the total spring rate more constant. Beneath the larger shock housing is a rubber accordion boot keeping the sliding surface of the shock body clean.

This is not just a Honda 750 with a big motor and a shaft drive, though. It’s also a Custom. That’s Honda’s word for the particular style of this motorcycle, a style that has become highly fashionable in the last two years since Yamaha introduced its Specials. The Custom appellation means the CB900 gets wide handlebars that bend far back. And it has a seat that’s more than a stepped seat but not quite a bucket seat. The seat is low and the pegs far forward so the seating position isn’t leaned forward or even upright. No, the CB900 Custom requires a particular slouch for things to fit.

Of course there’s a different gas tank on the Custom. It’s sort of like the tank on a>

Yamaha Special, with a bulging front section and tapering rear section; sort of like a Triumph or a BSA tank, but without knee pads. It does have the Honda wing, gold colored and resting on the Honda nameplate. It’s a good looking tank, and it doesn't get in the rider’s way w hile it holds a normal enough 4.5 gal. of gas, and after living with the Honda for a month, it makes one wonder why only Specials or Customs or the other semi-choppers get nice looking tanks.

A Custom just wouldn't be custom if it didn’t have a fat 16 in. rear tire and individual mufflers for each cylinder, all connected with a crossover tube. Fenders are chromed, by gawd, none of this flimsy plastic stuff on a Custom.

While the so-called normal motorcycles get integrated plastic boxes to hold the taillight and license plate and a tiny piece of plastic that functions as a fender and they come with molded housings for rectangular headlights and the instruments are grouped in clusters with gas gauges and digital readouts, the Honda looks like a motorcycle and it looks beautiful.

Better yet, the 900 works, by any measurement. as well as it looks. First, it is a performance motorcycle. Its quarter mile time of 12.29 sec. with a trap speed of 108.43 mph is better than that of the competition. The only shaft drive bikes with better times, and more power, are the Kawasaki KZ1300 and the Yamaha XS1100. The Yamaha XS850 is a second slower in the quarter. The Suzuki GS850 is four-tenths slower. Even the KZ1000 Shaft' with lOOcc more engine is two-tenths slower.

But quarter mile times are only one measurement of performance. There are others.

Handling performance is another CB900 strength. Though the wide bars and confining seat inhibit spirited cornering, the CB900 is a handling match for any Japanese shaft drive, the Honda and Suzuki being the best handling of the lot. The Honda’s biggest problems, handling wise, come from its almost-600 lb. weight and 62.2 in. wheelbase. With a half tank of fuel, the Honda tipped the scales at 597 lb. That’s 57 lb. and 1.7 in. of w heelbase more than the CB750F, 10 lb. and 2.65 in. more than the GS850. and 14 lb. and 0.95 in. more than the XS1000 Special. That weight and wheelbase means it takes effort to steer the 900, particularly back and forth in esses. It is stable and precise, not feeling vague like the CX500 or clumsy like the XS850. Only on bumpy surfaces at very high speeds would the 900 wiggle a little bit, and then the motion wasn't self perpetuating and quickly damped itself out.

Despite the weight and wheelbase and the 4-into-4 exhaust system, the Custom has excellent cornering clearance. Honda>

123

claims the lean angle is 48°, or slightly less than the 44° possible with the CB750F. It’s not surprising that the 900 can’t be leaned over as far as the 750, after all the 750 Honda is among the best handling motorcycles made. What’s surprising is how close the much heavier 900 can come to the 750’s performance. Heeled over hard, the footpegs touch on both sides of the 900 before anything like stands or exhaust scrape, giving the rider excellent notice of the bike’s limits. This is, considering its weight and adaptability, a great handling motorcycle.

Performance isn’t free, but the Honda gives up little for its power. The engine starts first thing at all temperatures. It can be ridden away as soon as it starts, even when the temperature is down around freezing. There is no hesitation or rideability problems like those of so many other emission controlled motorcycles. It has good—but not outstanding—power at

all engine speeds, torque building up with speed throughout the range. And it has a high redline, 9500 rpm, at which speed the engine fairly howls through the four megaphone-styled mufflers. Gas mileage, sadly, is not a strong point. On the average, the Honda returned 42 mpg. The best tank was 44.5 and the worst tank during street use was 31 mpg, both figures turned in during open road testing. The last Honda 750 tested got 48 mpg, Suzuki’s 850 gets about the same mileage, while Yamaha’s 850 got 47 mpg. Also, the Honda has the smallest gas tank of the bunch.

Comfort on the CB900 is great. But it could be better. The suspension is just superb. When the staff road race guys came back from the test track they wondered why the CBX doesn’t use this suspension. The damping is just right and the springingjust firm enough so the motorcycle is in control at the limits. Yet with the highly progressive air assist, normal riding

on the Honda is like a cloud. After a month, on the 900 any other motorcycle is. well, just another motorcycle.

In exchange for the fine ride, you get a seat that’s not Honda’s best effort. No one was comfortable on it. Being low. so short people (spelled 1-a-d-i-e-s) can ride the 900, there is little room between the seat and the pegs so tall people feel cramped. And the seat holds the rider in one place and one place only. There’s no place to stretch. A motorcycle like this will do wonders for the sales of highway pegs. The bars aren’t bad. as far as bucko bars go. They are wide, but don’t bend back as far as most do. And the grips, like those on all the big Hondas, are the best in the business.

All the bits and pieces that complete a motorcycle are helping rider comfort, not hurting it. The throttle is gentle to twist, the clutch is light and smooth engaging. The regular gearbox was normal Honda,

that is, light and smooth, although ours did hang up occasionally between 3rd and 4th, requiring an extra nudge. Brakes are light but don’t lock unnecessarily. The gauges are round, have black backgrounds with white numbers and pointers and are highly visible at night with white light that isn't overly bright.

Some common conveniences of modern motorcycles aren't on the 900 and it may not be any worse for it. The petcock is opened by the human hand, not suction from a carburetor. The same left hand both turns on and off the signal lights. The choke is cable operated by a knob at the handlebars, just beside the fuse box mounted at the base of the handlebars.

Then there is the double transmission. It can be considered a 10-speed, a five-timestwo-speed, a six-speed or any other combination. In practice, we left the subtransmission in the low range around tow n where the bike was easier to accelerate without bogging the engine. Once on the highway the rider looked down at the side of the motorcycle to find the second lever and shifted to the high range. Only one rider could find the lever without looking, and it wasn't easy for him. Simply put, there’s got to be a better way to shift the sub-transmission. We don't know what it is, Honda has tried other shifting mechanisms and this is the best one they thought of. Maybe next year there will be an improvement.

The difference between ratios works out to about 500 rpm at normal highway speeds. In the low range the engine is turning 4342 rpm at 60 mph while in high range it's turning 3839 rpm. It’s a difference worth having, though a straight six-speed transmission, adding an overdrive sixth onto the ratios of the low-range five gears would be much easier to use and more worthwhile.

Honda’s CB900 Custom is a successful motorcycle. No doubt about it. It is fast. It is comfortable. It is also serviceable with the fairing and saddlebags already made for it and the motorcycle designed to accept common touring accessories.

It is also not perfect. A less Custom-ized version should be offered. Give us a CB900K and a CB900F without the low seat and w ith shorter bars. Considering the gas mileage, the 900 needs a bigger tank, too. In its present form, the 900 Honda isn’t as good a specialized touring bike as the Suzuki GS850. For overall use, however, its greater power and more sophisticated suspension make the Honda a better bike, it’s just that Suzuki makes various models of the 850 to suit different markets.

It’s a matter of compromise. This may be the best compromised motorcycle Honda or anybody else has ever made, but there are still too many compromises about it to be the best-ever motorcycle for its intended use. It’s close though. SI

HONDA

CB900

SPECIFICATIONS

PERFORMANCE