CAN-AM 250 MX-6

The Quick One Now Handles

CYCLE WORLD TEST

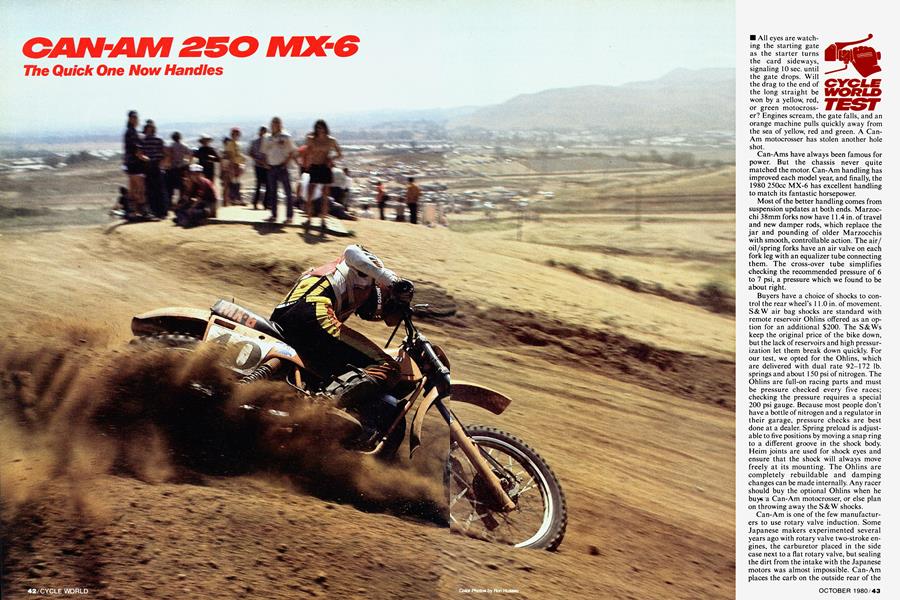

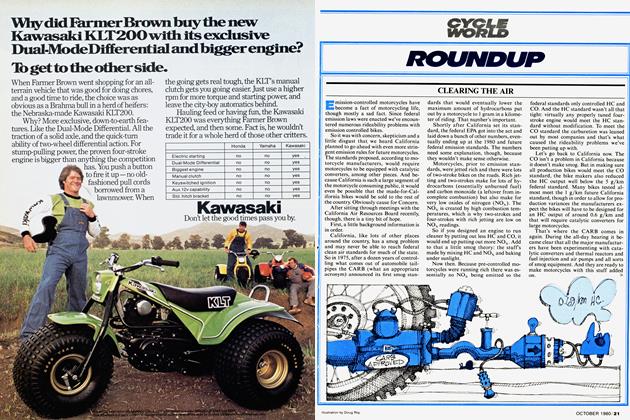

All eyes are watching the starting gate as the starter turns the card sideways, signaling 10 sec. until the gate drops. Will the drag to the end of the long straight be won by a yellow, red, or green motocrosser? Engines scream, the gate falls, and an orange machine pulls quickly away from the sea of yellow, red and green. A Can-Am motocrosser has stolen another hole shot.

Can-Ams have always been famous for power. But the chassis never quite matched the motor. Can-Am handling has improved each model year, and finally, the 1980 250cc MX-6 has excellent handling to match its fantastic horsepower.

Most of the better handling comes from suspension updates at both ends. Marzocchi 38mm forks now have 11.4 in. of travel and new damper rods, which replace the jar and pounding of older Marzocchis with smooth, controllable action. The air/ oil/spring forks have an air valve on each fork leg with an equalizer tube connecting them. The cross-over tube simplifies checking the recommended pressure of 6 to 7 psi, a pressure which we found to be about right.

Buyers have a choice of shocks to control the rear wheel’s 11.0 in. of movement. S&W air bag shocks are standard with remote reservoir Ohlins offered as an option for an additional $200. The S&Ws keep the original price of the bike down, but the lack of reservoirs and high pressurization let them break down quickly. For our test, we opted for the Ohlins, which are delivered with dual rate 92-172 lb. springs and about 150 psi of nitrogen. The Ohlins are full-on racing parts and must be pressure checked every five races; checking the pressure requires a special 200 psi gauge. Because most people don’t have a bottle of nitrogen and a regulator in their garage, pressure checks are best done at a dealer. Spring preload is adjustable to five positions by moving a snap ring to a different groove in the shock body. Heim joints are used for shock eyes and ensure that the shock will always move freely at its mounting. The Ohlins are completely rebuildable and damping changes can be made internally. Any racer should buy the optional Ohlins when he buys a Can-Am motocrosser, or else plan on throwing away the S&W shocks.

Can-Am is one of the few manufacturers to use rotary valve induction. Some Japanese makers experimented several years ago with rotary valve two-stroke engines, the carburetor placed in the side case next to a flat rotary valve, but sealing the dirt from the intake with the Japanese motors was almost impossible. Can-Am places the carb on the outside rear of the

engine, in a more conventional location, and ducts the fuel through a long intake tube to the rotary valve. The Can-Am system seals properly, jetting and maintenance is simple, and the honed-to-perfection engines continue to out-power reed valve engines.

Engine power is noticeably stronger on the motocrosser than the recently tested Can-Am 250 Qualifier. The biggest differences are the MX-6’s 34 mm Mikuni carburetor (vs. the Qualifier’s 32mm Bing), exhaust port raised 1mm, lighter flywheel, and a different pipe and silencer. The rotary valve cutout, normally lengthened to produce more power on rotary valve engines, is the same. Like past CanAms, the cylinder has a steel cylinder liner that can be bored to four oversizes. The cylinder and head are wide and covered with lots of fins so overheating isn’t a problem.

Although the basic engine has been around several years, the countershaft sprocket is placed on the rear of the motor—the swing arm and sprocket centers are just 3.1 in. apart. Engine cases are made from magnesium and large hardened bolts with self-locking nuts hold the engine securely in place. The 250 MX-6 has a five-speed transmission instead of a six-speed like the Qualifier. Low is low enough to use the bike as a play bike and is usually unnecessary on most MX courses. Second is the gear most used for motocross starts. Gear ratios between second and fifth are perfectly spaced for the engine’s torque and power curve.

Ignition is Bosch CDI with an outside flywheel. Timing is checked using a timing light with the engine running. An inspection plug is provided for timing so the complete side case need not be removed.

The engine shows concern for the rider who competes in wet areas. The flywheel

cavity, transmission, and carburetor vent and overflow tubes terminate in a bracket located just below the seat, the bracket itself made from a flat plate and looped pieces of tubing. All of the vent hoses connect to one end of the looped pipes, so water can’t be siphoned or splashed into the trans or carburetor or the magneto cavity (which is vented so condensation won’t rust the parts).

The frame is different from past CanAms although it looks the same to a casual observer. The large backbone used to be an oil reservoir when oil injection was a standard feature. Now it’s used to funnel fresh air from behind the number plate to the air box. Two scoops, one on each side of the steering stem, divert air to the frame backbone and straight into the top of the air box. Any water that enters is drained from the lower rear of the frame tube by a large diameter plastic tube. The seat seals the top of the air box so incoming air can come only from the area behind the number plate. Once the air gets inside the air box, it is filtered through two filter elements, a thin foam filter being fitted over a K&N cloth filter. The K&N filter screws into the bottom of the air box, making removal easy once the seat is removed. (More about seat removal later.) The threaded part of the box’s bottom is elevated so dirt and grime can’t fall into the still air box (located directly below the filter box) when the element is removed. In theory a still, or dead, air box located between the air cleaner and carburetor is the correct way to do things, but Can-Am is the only manufacturer we can think of to still use one. Overall, the induction system works, and works well. Air coming from behind the numberplate is generally cleaner than that available directly in front of a spinning rear wheel and water isn’t easily splashed into the duct system.

And deep water crossings are a breeze. If the water level is above the air intake you’ll need a boat anyway.

The rest of the frame is generally the same chrome-moly unit Can-Am has used for a couple years. Small double front downtubes roll under the engine, then turn upward and terminate at the rear of the main backbone. Two tubes start just above the swing arm pivot and go forward to a point about the middle of the backbone. Others start above the pivot and go up and rearward where they curve to parallel the seat rails and form a mounting point for the shocks. A flat strap connects the back of the seat rails and provides a convenient place to bolt the rear fender. The frame design looks a little busy but provides maximum triangulation to the mid-section of the frame.

The swing arm is constructed from chrome-moly steel and has a banana bend to it. It pivots on bushings instead of needle bearings. The center of each bushing is steel, with a Nylotron outside, made of a nylon material impregnated with graphite. The mixture is strong and wear resistant, excellent for swing arm bushings. Dirt and water are kept out of the bushings by an O-ring seal at each side of the bushing and the swing arm unit is fitted to each frame with shims, ensuring a slopfree fit.

Past Can-Ams had adjustable steering head angles. Most buyers didn’t take advantage of the adjustability so it has been dropped on the new models. Rake is how set at 29° but the older adjustable cones can be installed if an owner wants quicker or slower steering. We found it perfect as is.

Wheel assemblies on the MX-6 are first rate. The front is a conical unit that is unchanged from last year. It contains a strong progressive brake and it’s laced to an American-made Sun rim. Sun rims have the reputation of being the strongest made and we have found the reputation to be deserved. Small spikes in the area that contacts the tire bead do away with conventional rim locks and makes tire changing less a chore, but still hold the tire in place better than regular rim locks. The rear wheel also uses a Sun rim, an extrawide model that spreads the tire beads, effectively increasing the tire contact patch to increase traction during acceleration and braking. It’s laced to an all-new hub that has both the sprocket and the brake on the same side. A full-floating backing plate is used and the brake is operated by a heavy cable which further isolates it from locking the suspension. The brake static arm is fabricated from tubing and has a chain guide and cable holder welded just aft of center. The chain guide is a small block and looks like it’s placed too far in front of the rear sprocket but we didn’t experience any chain problems, so, it must work. We did feel some rear wheel chatter on rough downhill situations if the

brake was used real hard. We traced the problem to a cable housing that fit too tight in the holder. Carefully removing part of the outer cable housing (it’s a double housing) allows the cable to move around and the chatter stops. The new hub has a wide spoke pattern and this wide pattern and Sun rim allows the use of small spokes.

Most of the Can-Am’s plastic parts are made by one of parent company Bombardier’s plastic fabricators. The exception is the front fender, a Petty MX model. The rear fender does a good job of keeping water and mud off the operator, but like the square-design side plates, draws mixed reactions from different people: some think the square shapes are neat, others cut the side plates into ovals and install oval number backings. The 2-gal. plastic tank and super-comfortable seat are also squarish. The tank is narrow and mounted low on the bike. The seat has thick foam and a plastic base. The thick seat and low tank make moving forward on the machine super easy because the top of the seat and top of the tank are almost the same height. Removing the seat is a minor hassle because six bolts hold it on, but it’s not as difficult as might be expected. Five of the bolts can be reached with a socket, and removal isn’t necessary

very often, thanks to the unique air intake system and the K&N filter, which doesn’t require frequent cleaning.

We found people judging the MX-6 by its looks: if they didn’t like the square numberplate design, they thought they wouldn’t like the machine. Although it’s a natural reaction, judging a machine strictly by looks, it’s almost always a mistake. In the case of the MX-6, it’s a big mistake. The MX-6 is a very competitive motocross bike.

Starting is always first kick with the left side kick lever. The leverage required to spin the engine is slight and the engine turns several times with each prod. It never back fires or kicks back, just fires and runs. Once running it’s quiet and nonfussy. All controls are properly placed and shaped. Clutch pull is easy and the fivespeed transmission shifts into low without lurching.

The MX-6 is an extremely easy bike to get the hole shot with. Just lift the folding shift lever up to second, turn the throttle half open (most 250s require full throttle for good starts), bite the front fender and let the clutch out quickly. The bike will shoot from the starting gate like a dragster every time. And once out of the gate, it doesn’t snake around or try to loop. The front wheel stays on the ground and the

rear gets traction. Upshifts are smooth and fast, and gear ratios are perfect for the engine’s horsepower and torque curve. On most MX courses just the top four gears are needed. The rider doesn’t have to shift nearly as much as is necessary on most 250 motocrossers and the broad power means gear selection is less critical, much like an open bike.

Staying in front of the pack after the start straight isn’t a problem either. The MX-6 is like a Maico in corners. Any line is the hot line, inside or out. And changing lines part way through a corner due to a fallen competitor is easy. The rider is in full control in flat as well as bermed turns. The bike goes through a berm like it was on rails. Or the rider can use the berm to make a square turn; the rider chooses, not the bike. The bike is very neutral handling and the rider doesn’t have to adapt to any special bike quirks or have to change his riding style to fit the bike’s requirements. Just hop on and the bike becomes an extension of the rider. The neutral handling traits are evident fore and aft as well. If the rider desires the front wheel in the air, the engine will easily lift it. Otherwise, it stays on the ground and won’t fly itself. And the bike never dives, lists or tries to loop over jumps. This kind of handling gives instant confidence to the rider. Any>

CAN-AM

250 MX-6

$2199

rider from novice to pro is comfortable on the MX-6 and modifications won’t be necessary to make the bike competitive if the optional Ohlins are bought with the bike.

Total suspension travel won’t awe anyone but 11.4 in. front and 11.0 in. rear is enough when it works well, as it does on the MX-6. We have complained about roughness in the Marzocchi forks for years and finally they have changed the damping rods. The new internals are made from aluminum and work great. The forks are compliant to the smallest bump but don’t bottom unless pushed extremely hard, then bottoming is gentle. The shocks are almost as good. They aren’t dialed in perfectly for our test riders but they are close. We would prefer slightly lighter primary spring rates but otherwise can’t complain. Control of the bike is good and both wheels follow the ground well. Shock to the rider is light due to the spring rate of the shocks, but not objectionable. The front forks work as

well as any we have ever experienced. One complaint is the quality of the crossover tube for the fork pressurization. The material isn’t up to the task and started leaking air and oil after three races. We went to individual air valves and stopped the problem, but better quality tubing should be used so the problem wouldn’t exist.

Part of our testing involves testing motocross bikes at motocross races with a pro racer aboard. The Can-Am proved extremely competitive and fun. We raced the MX-6 in five different races at the pro level. Finishing positions were sixth twice, second once, and first twice. Although the rider was outridden a couple of times, the bike was never out-run due to lack of power or acceleration. And it proved competitive on the roughest ground against single shock designs. But best of all, it never broke or let us down; quite a record for so many races. Even the spokes that look a little small, held up fine. We didn’t break a single one. Much of the credit has

to go to the Sun rims that don’t get eggshaped and cause loose spokes.

Some of the races were raced in mud. The wide powerband and progressive brakes are desirable assets when conditions become adverse. So are the sawtoothed tops on the rear brake pedal and footpegs. And the completely open bottom on the footpegs lets the mud fall through the pegs to keep the gripping power through a long race.

Complaints are few. The crossover air tube for the forks we already talked about. The footpeg springs are a little wimpy and we broke one, but the footpeg still returns with the spring broken. And the front brake should be placed on the opposite side of the machine so the cable doesn’t have to make such a tight bend, but... we can’t think of a single 250cc motocrosser we enjoyed riding and racing more. It just goes to show that development of an existing design is sometimes better than an allnew design. El