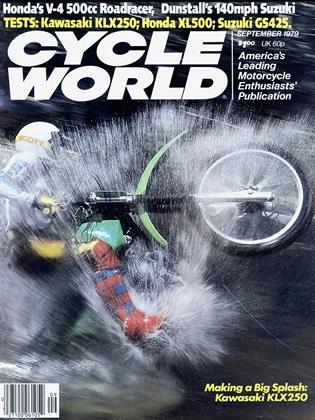

KAWASAKI KLX250

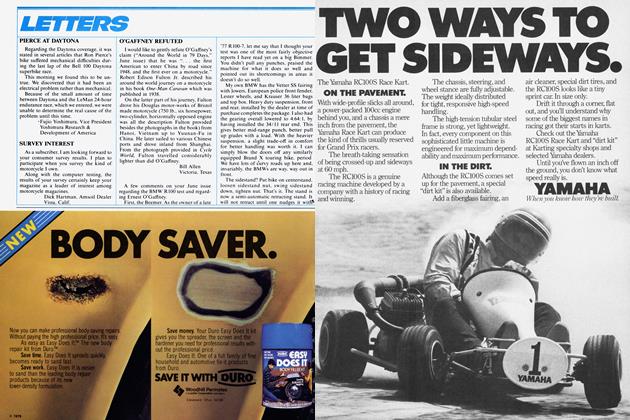

CYCLE WORLD TEST

A Four-Stroke Dirt Bike That HANDLES

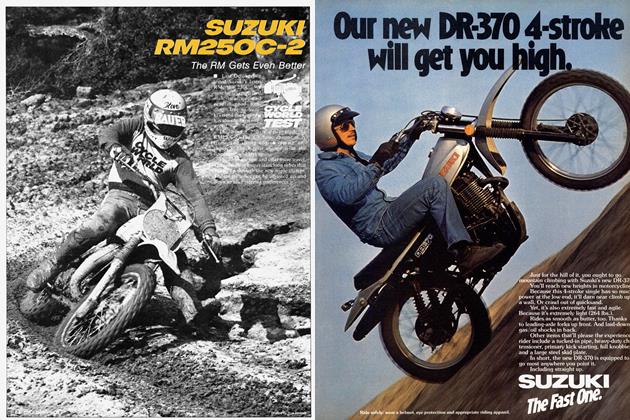

The last couple of years have seen the return of the four-stroke Single dirt bike. Yamaha started the ball rolling with the TT500 and Suzuki followed with the DR370. Then Honda introduced its long awaited XR series of machines. All of those bikes had frames and other major parts engineered especially for them. It seemed funny that no manufacturer had used an already good handling motocross chassis. Mating a four-stroke Single to a motocross chassis should be the easy way to get a good handling, lightweight, new line of models. Design new mounts, move things around a bit, brace or rework the frame as needed and presto, the engine swap becomes a production machine. The backyard crowd has done this for years, but the factories? Never.

Finally Kawasaki has done the obvious.

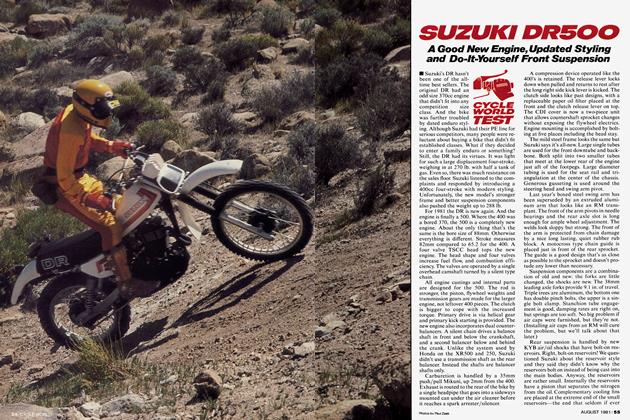

Kawasaki calls its creation the KLX. Starting with a KX125 motocrosser the frame was altered to accept an engine from the KL250 four-stroke dual purpose bike.

There isn't anything particularly trick about the KL engine. It doesn't have counter balancers or a four-valve head. It's just

a conventional two-valve head set up with a single overhead cam and single head pipe. Not to say there is anything w rong with a simple, non-fussy, straightforward design. Quite the opposite. Bv keeping things simple, engine weight has been> kept down. Total weight of the KLX engine with the kick starter and carburetor is only 75 lb.

A few changes have been made to the KL motor as seen in the KLX. Previously the entire side cover had to be pulled to change the oil filter—a poor design. Now there’s a separate housing for the oil filter that’s easy to remove. The battery and points of the KL motor have been left off and there’s now a CDI unit hidden on the left side of the cam where the points used to be. The cam still spins directly on the head without benefit of replaceable bearings.

This lightweight engine combined with a chrome-moly steel frame from Kawasaki’s KX125 motocrosser produces a fourstroke enduro/play bike that weighs 243 lb. with a half tank of fuel. This is 50 lb. lighter than Kawasaki’s KL250 and 25 lb. lighter than a Honda XR250. Since the Kawasaki KL uses the same engine as the KLX, the giant weight reduction has come from using the motocross chassis.

The frame is a large single downtube design fabricated from chrome-moly tubing. It is heavily triangulated around the steering head and the area under the seat. A few changes were necessary to make the frame fit the KLX’s intended use. Naturally, engine mounting tabs had to be redesigned. The engine mounts in five places and adds to the solid feel the machine has. A couple of other small changes were also made to the motocross frame. A rear fender loop was added and designed so it could be used as a grab handle. The steering rake was steepened to 28°. The steeper rake makes the bike more agile on tight trails and combined with a tight turning radius, makes it easy to ride around switchbacks that are too tight for most machines to negotiate without backing up at least once.

The new KLX has one American made part—the aluminum swing arm. We first saw this swing arm on the half-American, half-Japanese Kawasaki KDX. It is a massive I-beam design that provides strength while keeping weight down.

Forks, shocks, plastic fuel tank, fenders, wheels and brakes are straight from the 125 motocrosser.

Wheel travel at both ends is around 10 in., more than enough for any trail situation. But more important than total travel is the quality of the travel. And the quality of the KLX’s suspension is excellent. The leading axle, motocross forks and reservoir shocks are compliant on the smallest bumps, yet don’t bottom hard on large ones. Harshness is never felt. Holes, rocks, and cross ruts are taken without jolting the rider. Spring rate and damping are spot on. Making an improvement to the suspension on a KLX will be indeed hard.

Beautiful conical hubs from the KX125 are used and do an admirable job of stopping the machine. They are strong, progressive and predictable. The rear has a full-floating backing plate that prevents chatter and hop when used hard on bumpy downhills and they aren’t affected much by deep water crossings. Wheel rims are aluminum and don’t pack with mud. Spokes are medium sized and once seated did their job fine. Tires are Bridgestone’s latest.

Tank and fenders are stock 125 motocross items. The plastic tank holds 2.5 gal. of fuel and won’t bend if the rider crashes or drops the machine. Fenders are also plastic. They are flexible and strong but a little small for serious enduro use. Charging through deep water will result in the rider getting wet. For casual use they are fine.

The KLX doesn’t have a speedometer. It has an odometer similar to the one used on Suzuki’s PE enduros, but better. It logs mileage up to 99 mi. on the left side and is resettable. The right side gives total mileage and can’t be reset.

Although the excellent odometer says serious enduro, the bike doesn’t have lights as standard equipment. Because many play bike buyers remove the lights, Kawasaki decided to make them an option. The optional lighting kit is the same thing used on the KDX400 tested last month (Aug.'79). The kit consists of a headlight/ number plate, small taillight, and necessary wiring. The headlight/number plate attaches with supplied rubber straps, and the wiring is color coded. The taillight requires drilling a couple of holes in the rear fender. Installation time is about 20 min. Price is $49.

Bars, levers, pegs and seating position are just right on the KLX. The short tank and long seat place the rider forward on the machine. Seat height is on the tall side at 36.7 in. but the soft suspension has some sag to it so the unladen height figures are somewhat misleading. Actual ride height is quite a bit lower than the figures indicate but a short rider will still have trouble when it comes time to turn the bike around on uneven ground.

The little four-stroke is easy to kick over but it usually doesn’t start on the first kick.

Most of the time three or four kicks are required to bring it to life. Engine temperature seemed to have little to do with the number of kicks required; it almost always needed several.

Once running, the exhaust note is raspy, almost too loud for such a tame engine. The raspiness disappears as soon as the bike is under way though. The small silencer contains a U.S. Forest Service approved spark arrester and double mounting brackets are used. The head pipe has been carefully routed and doesn’t have or need a heat shield to keep from burning the rider. The only problem with it was a slightly melted Scott boot that touched during a photo shoot. The careful routing has also eliminated the need to flatten the pipe for clearance near the rear wheel and frame section. By routing the pipe higher just aft of the motor, and molding the airbox around it, adequate clearance is possible without smashing the pipe almost shut.

The difference between a KLX and KL is enormous. The 50 lb. weight difference and motocross chassis make for an entirely different bike. The only thing the same is the soft power. With the huge reduction in> weight and a larger 32mm carburetor, performance should be drastically improved but it’s hard to tell any difference. Horsepower figures tell us the unit churns out 21 bhp but it feels like less. All of our test riders complained about the lack of power. The engine has to be rung out like a 125 motocrosser and almost abused if the rider wants to ride aggressively. Engine response is sluggish and revs build slowly. A Honda XR250 feels like a powerful bike in comparison.

If a cross rut or gully suddenly pops up in front of you when aboard a KLX. forget about pulling the front wheel up with a blip of the throttle, you can’t. But the chassis and suspension are so good the machine will go through without throwing the rider off. It is possible to fly the front wheel on a KLX, but it takes a special technique. By cruising in second, quickly turning the throttle open, fanning the clutch and tugging, the front will come up, but it takes practice and a good rider. Once up. balance is excellent and the machine doesn’t try to fall over or loop.

A couple of test riders dragged the skid plate when bottoming the suspension through ditches and such. The ground clearance is almost an inch less on the KLX than it is on a 125 motocrosser. Because the four-stroke engine is taller than the two-stroke motocrosser. the frame’s cradle has been lowered. Wheel travel stayed the same, so it becomes easier to drag the skid plate. The problem isn't bad enough to cause trouble with control of the bike, but some riders will be aware it is happening.

General handling is hard to fault. The KLX steers as precisely as a multi-buck custom. If Maico made a four-stroke single, one would expect it to steer like the little KLX. Precarious trails can be ridden with complete confidence. Rocks, tree roots and other hazards are easily steered around, not smashed into.

The KLX is a natural for wet areas. We jumped it into a 30 in. deep creek for over an hour and it didn’t even sputter. The brakes weren’t affected either. They stopped as well after the submerging as before. The Bridgestone tires also match the wet area character of the KLX. They work well in mud, on damp trails and sand. They are less than great, however, on slippery hard pack.

We had a ball testing the KLX. We took it to the mountains several times and to the desert once. It handles well everywhere. If the engine produced five or six more horses, it would be even better. When fast whoops are encountered, there simply isn’t enough power available to keep the front end light. If the rest of the package wasn’t so good, this would be a real problem. But the KLX refuses to handle badly. It stays arrow straight through whoops and ditches. A solid feel is always present and it doesn’t twist or flex. It is one of the most rigid machines we have tested. Even when the suspension has bottomed in a rock whoop, the bike has a solid, unbending feel.

The KLX is a real miser when it comes to gas consumption. The 2.5 gal. tank will take a hard rider over 100 mi., while an easy rider will be able to go over 125 mi.

Complaints were few on the KLX. One tester didn’t like the seating position, the short testers disliked the seat height, one thought the push-pull throttle turned too hard, all thought the engine needed more power.

KAWASAKI KLX250

$1649

So what does a prospective buyer get for his $1649? Near perfect chassis, excellent brakes, excellent suspension, and an understressed four-stroke engine that will probably run forever.

Except for the nitpicking, the KLX was right on. It will probably be perfect for many uses. Picking a better machine for use in the forests would be hard indeed. With the optional lighting kit and a little hop-up on the engine, the bike could easily win an eastern-type enduro. The play rider who wants reliability but also demands good handling, will love the KLX.

The KLX is a milestone in four-stroke off-road machinery. Kawasaki has done what many Americans have been doing for years—put a reliable four-stroke engine in a proven chassis. Seems funny it took so long for a major company to catch on.

Now where is the 500? @