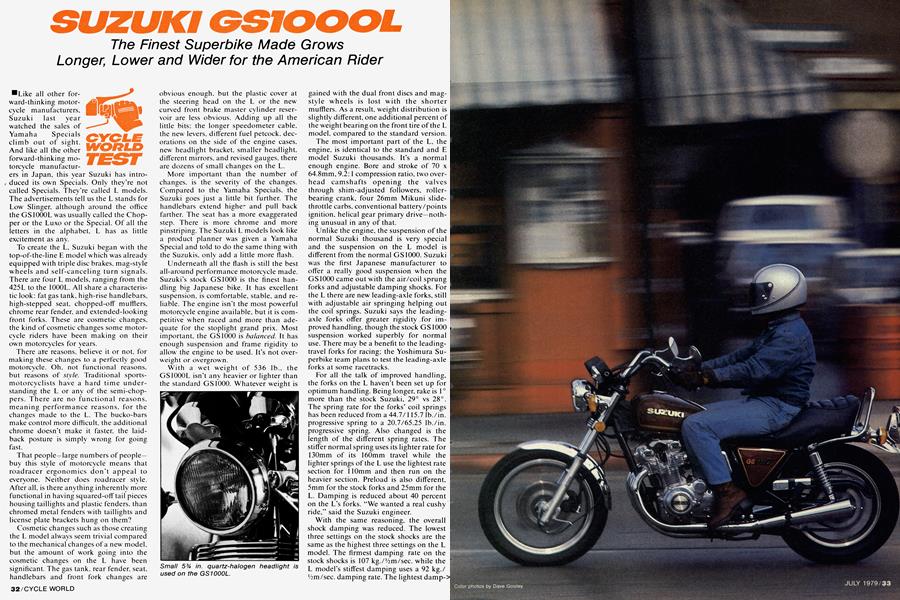

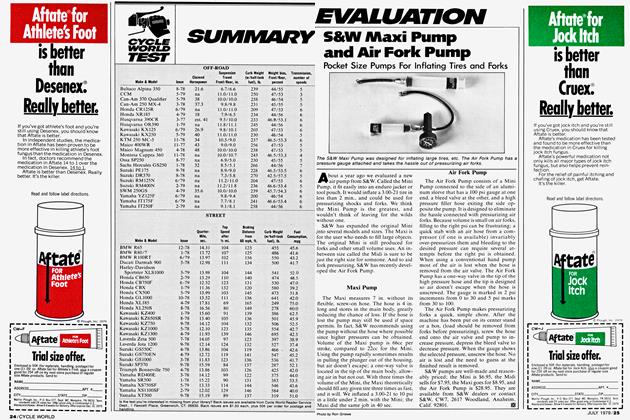

SUZUKI GS1000L

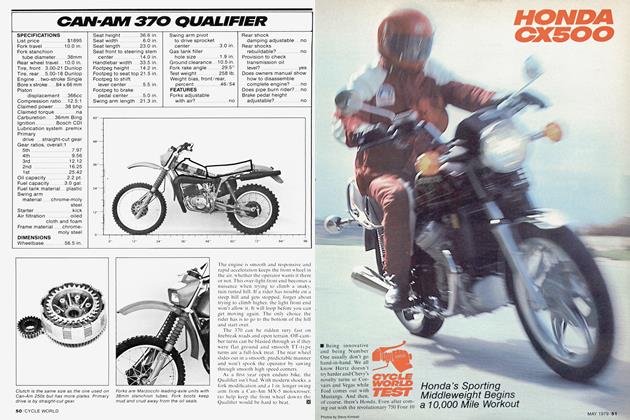

CYCLE WORLD TEST

The Finest Superbike Made Grows Longer, Lower and Wider for the American Rider

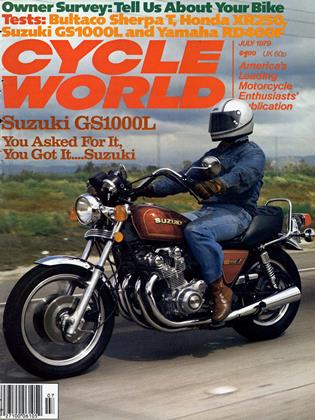

Like all other for-ward-thinking motorcycle manufacturers, Suzuki last year watched the sales of Yamaha Specials climb out of sight. And like all the other forward-thinking motorcycle manufactur-

ers in Japan, this year Suzuki has introduced its own Specials. Only they’re not called Specials. They’re called L models. The advertisements tell us the L stands for Low Slinger, although around the office the GS1000L was usually called the Chopper or the Luxo or the Special. Of all the letters in the alphabet, L has as little excitement as any.

To create the L, Suzuki began with the top-of-the-line E model which was already equipped with triple disc brakes, mag-style wheels and self-canceling turn signals. There are four L models, ranging from the 425L to the 1000L. All share a characteristic look: fat gas tank, high-rise handlebars, high-stepped seat, chopped-off mufflers, chrome rear fender, and extended-looking front forks. These are cosmetic changes, the kind of cosmetic changes some motorcycle riders have been making on their own motorcycles for years.

There afe reasons, believe it or not. for making these changes to a perfectly good motorcycle. Oh. not functional reasons, but reasons of style. Traditional sportsmotorcyclists have a hard time understanding the L or any of the semi-choppers. There are no functional reasons, meaning performance reasons, for the changes made to the L. The bucko-bars make control more difficult, the additional chrome doesn’t make it faster, the laidback posture is simply wrong for going fast.

That people—large numbers of peoplebuy this style of motorcycle means that roadracer ergonomics don’t appeal to everyone. Neither does roadracer style. After all. is there anything inherently more functional in having squared-off tail pieces housing taillights and plastic fenders, than chromed metal fenders with taillights and license plate brackets hung on them?

Cosmetic changes such as those creating the L model always seem trivial compared to the mechanical changes of a new model, but the amount of work going into the cosmetic changes on the L have been significant. The gas tank, rear fender, seat, handlebars and front fork changes are obvious enough, but the plastic cover at the steering head on the L or the new curved front brake master cylinder reservoir are less obvious. Adding up all the little bits: the longer speedometer cable, the new levers, different fuel petcock. decorations on the side of the engine cases, new headlight bracket, smaller headlight, different mirrors, and revised gauges, there are dozens of small changes on the L.

More important than the number of changes, is the severity of the changes. Compared to the Yamaha Specials, the Suzuki goes just a little bit further. The handlebars extend higheand pull back farther. The seat has a more exaggerated step. There is more chrome and more pinstriping. The Suzuki L models look like a product planner was given a Yamaha Special and told to do the same thing with the Suzukis. only add a little more flash.

Underneath all the flash is still the best all-around performance motorcycle made. Suzuki’s stock GS1000 is the finest handling big Japanese bike. It has excellent suspension, is comfortable, stable, and reliable. The engine isn't the most powerful motorcycle engine available, but it is competitive when raced and more than adequate for the stoplight grand prix. Most important, the GS1000 is balanced. It has enough suspension and frame rigidity to allow the engine to be used. It’s not overweight or overgrown.

With a wet weight of 536 lb., the GSIOOOL isn’t any heavier or lighter than the standard GS1000. Whatever weight is gained with the dual front discs and magstyle wheels is lost with the shorter mufflers. As a result, weight distribution is slightly different, one additional percent of the weight bearing on the front tire of the L model, compared to the standard version.

The most important part of the L, the engine, is identical to the standard and E model Suzuki thousands. It’s a normal enough engine. Bore and stroke of 70 x 64.8mm, 9.2:1 compression ratio, two overhead camshafts opening the valves through shim-adjusted followers, rollerbearing crank, four 26mm Mikuni slidethrottle carbs. conventional battery/points ignition, helical gear primary drive—nothing unusual in any of that.

Unlike the engine, the suspension of the normal Suzuki thousand is very special and the suspension on the L model is different from the normal GS1000. Suzuki was the first Japanese manufacturer to offer a really good suspension when the GS1000 came out with the air/coil sprung forks and adjustable damping shocks. For the L there are new leading-axle forks, still with adjustable air springing helping out the coil springs. Suzuki says the leadingaxle forks offer greater rigidity for improved handling, though the stock GS 1000 suspension worked superbly for normal use. There may be a benefit to the leadingtravel forks for racing: the Yoshimura Superbike team plans to test the leading-axle forks at some racetracks.

For all the talk of improved handling, the forks on the L haven’t been set up for optimum handling. Being longer, rake is 1 ° more than the stock Suzuki, 29° vs 28°. The spring rate for the forks’ coil springs has been reduced from a 44.7/115.7 lb./in. progressive spring to a 20.7/65.25 lb./in. progressive spring. Also changed is the length of the different spring rates. The stiffer normal spring uses its lighter rate for 130mm of its 160mm travel while the lighter springs of the L use the lightest rate section for 110mm and then run on the heavier section. Preload is also different, 5mm for the stock forks and 25mm for the L. Damping is reduced about 40 percent on the L’s forks. “We wanted a real cushy ride,” said the Suzuki engineer.

With the same reasoning, the overall shock damping was reduced. The lowest three settings on the stock shocks are the same as the highest three settings on the L model. The firmest damping rate on the stock shocks is 107 kg./V^m/sec. while the L model’s stiffest damping uses a 92 kg./ Vim/sec. damping rate. The lightest damp-> ing position of the L is only 54 percent as stiff as the firmest setting, the No. 2 position is 67 percent, the No. 3 position is 84 percent. The ratio between settings is similar for both. Spring rates on both standard and L model are the same. Again, the lighter damping will presumably provide a smoother ride.

Cushy also describes the seat. At least to the hand it feels cushy. Suzuki says they use two layers of foam, a soft foam so the prospective customer can feel how soft the seat is with his hand, and a firmer foam which does the cushioning job. Trouble is, the L model just doesn’t have enough of the firm foam so the rider feels as though he’s sitting directly on the seat base. The passenger gets about 10 times as much foam to sit on and subsequently gets to perch up in the fresh air above the rider.

. Ergonomics are very personal. While the majority of the test riders at Cycle World don’t favor the semi-chopper look and its accompanying posture, there are right ways and wrong ways of creating the posture. The pull-back bars of the L aren’t far off the mark. They are a bit too wide and extend farther to the rear than necessary, but the shape isn’t excessive for the style.

However, put together with the saddle and the footpegs, the riding position of the L is about as uncomfortable as any bike ever made. When Laidback Larry cruises the boulevards, he is commonly leaning back, his feet stretched out in front of him. The 1979 Suzukis all have folding footpegs, new this year, and a racer’s delight. But the pegs are about 2 in. higher than the non-folding pegs used on earlier thousands and, when combined with the low seat, make for super-cramped, almost squatting position legs on a tall rider. To complete the semi-chopper posture the footpegs should be moved forward about a half-foot. Most of those who purchase an L will probably install highway pegs to solve the problem. Highway pegs will improve the situation, but detract from control of the motorcycle because the feet have to be moved back to the stock pegs for control of the shifting and rear brake.

Because the bucko-bars extend so far back, a rider is naturally sitting either upright or leaning slightly back while riding the L. On the normal bike, a rider leans slightly forward, his weight being partially supported by the wind pressure on his chest. With the upright posture, the wind pressure pushes a rider back too much, and the seat punishes a rider over any bumps that dare force themselves through the mushy suspension.

On a longish ride, one feature of the L stands out: the throttle return spring. If the throttle return spring were wrapped around the rear shocks, the L would have the load capacity of a dump truck. Fifty miles from home on a 300 mile ride, one rider pulled to the side of the road and. with both hands, pulled the spring completely off the throttle linkage. Because the Suzuki uses two throttle cables, one to pull the throttle linkage open and another to pull the linkage closed, the return spring isn’t actually necessary. There are no return springs in the carburetor slides. Removing the return spring isn’t recommended. but anyone considering long trips on the L may want to investigate replacing the throttle spring with a lighter spring.

With a lighter throttle return spring installed, other items of discomfort become noticeable. The Suzuki Four is generally a smooth running powerplant, but the long handlebars resonate the natural vibration of the engine, sending a harsh vibration through the handgrips at about 3000-4000 rpm. Not much vibration comes through the footpegs or the seat, but the handgrip vibration is greater than the vibration on any other Four. The vibration doesn’t irritate the stubby mirrors much, though. Unlike other Suzukis, the 1000L doesn’t use the rubber-bushed mirror stalks, but the solid mount mirrors are acceptably clear.

Other control and comfort items are much better. Dog-leg levers with moderate clutch and brake pull, convenient switches, self-canceling turn signals that turn off at just the right time, easy-to-read gauges bathed in a gentle red light, digital gear readout, and choke knob conveniently positioned at the steering head all lend an air of luxury to the L.

Taken as a whole, riding the GS1000, even the L, is a pleasurable experience. Using both hands (one for the clutch because of the interlock, the other for the starter button), the L starts easily. It’s slightly cold blooded, enough to be noticeable, but not nearly so sensitive as the GS850 or GS750. It snicks into gear easily, there’s enough low-end power to get under way without trauma, and the clutch takes hold smoothly and positively. At low speeds the short mufflers let a pleasantly hushed howl escape. Twist the right grip harder and the howl turns into a scream as the Suzuki rockets away. If the power band > were more pronounced, like the smaller Suzukis, the thousand would be a Jekyll/ Hyde bike. But the transition is so smooth there is little cause for alarm. The GS1000L doesn’t coerce a rider into demonstrations of speed, it allows the rider to go as fast as he wants.

Suzuki has quit listing horsepower or torque figures for its bikes, but the 1979 1000 engine is identical to last year’s engine which was listed at 83 bhp at 8000 rpm and 58 ft. lb. of torque at 6500 rpm. This year’s test bike, however, made a

fastest quarter mile run of 12.48 sec. at 107.39 mph while last year’s bike did 11.83 sec. at 112.07 mph. This year’s bike is definitely less powerful than last year’s bike, but it's still one of the fastest motorcycles on the road.

When it comes time to stop, the GS1000L is just as capable. The brake calipers on the twin front discs appeared different from the GS1000E, even though both are supposed to share identical brakes. Turns out there are two different suppliers of the brake calipers, both have

the same performance specifications, but the exterior appearance is slightly different. There has been a slight change to the brake pad material in this year’s Suzuki. Technical spokesmen for Suzuki say the new pads were a general improvement of pad composition designed to reduce squeal and improve wet-weather braking ability.

That last change, improved wet braking, is most noticeable on the new L. Previous Suzukis. like other disc-braked Japanese motorcycles, lost braking power when the brakes were wet. requiring riders to constantly ride the brakes in wet weather to keep them working or to forget about stopping in the wet. The new pad material appears to have eliminated the problem, plus the braking power and control of the brakes is first class.

No doubt about it, the GS1000 is a superlative motorcycle in any configuration. At $500 more than the standard GS1000, the L had better offer more than the standard bike. At a suggested retail price (as of this writing) of $3669. the L is also $110 more than the GS1000E which has the same cast alloy wheels and triple disc brakes. The difference is style. Style is tough to evaluate, because everyone has their own style. But there are strong points and weak points to the L’s style: the gas tank is too fat; the little plastic cover plates over the frame tubes in front of the gas tank look tacky; the overall quality of finish is excellent.

Suzuki is banking on a continued demand for customized motorcycles. The demand was enough to boost Yamaha’s market penetration significantly last year, but unless the semi-chopper fad grow'S enormously, the semi-chopper market is going to be spread thin by all the Yamaha Special-imitators. Now' that all the Japanese manufacturers offer quasi-Sportsters. no company will be losing or gaining a share of the market, just retaining what thev already have.

It doesn’t matter that the GS 1000L is no better motorcycle than the GS1000. Longer. Lower and Wider has always worked.

SUZUKI GS1000L

$3669