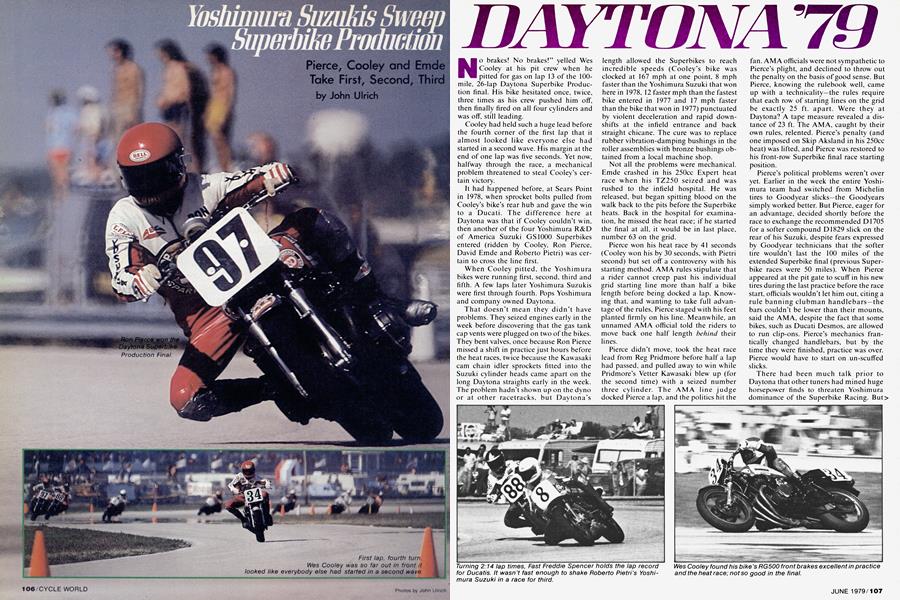

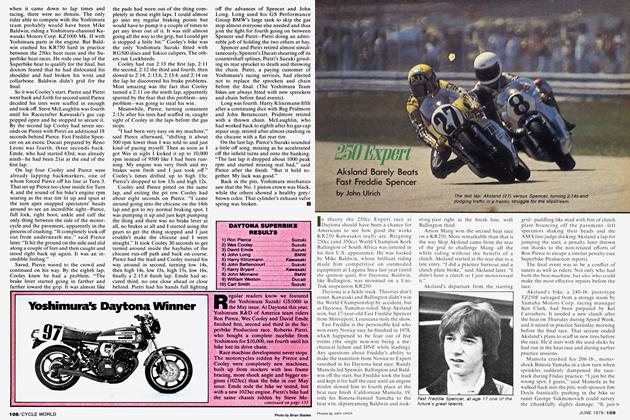

Yoshimura Suzukis Sweep Superbike Production

June 1 1979 John UlrichYoshimura Suzukis Sweep Superbike Production

Pierce, Cooley and Emde Take First, Second, Third

John Ulrich

DAYTONA '79

No brakes! No brakes!" yelled Wes Cooley at his pit crew when he pitted for gas on lap 13 of the 100-mile, 26-lap Daytona Superbike Production final. His bike hesitated once, twice, three times as his crew pushed him off, then finally fired on all four cylinders and was off, still leading.

Cooley had held such a huge lead before the fourth corner of the first lap that it almost looked like everyone else had started in a second wave. His margin at the end of one lap was five seconds. Yet now, halfway through the race, a mechanical problem threatened to steal Cooley's cer tain victory.

It had happened before, at Sears Point in 1978, when sprocket bolts pulled from Cooley’s bike’s rear hub and gave the win to a Ducati. The difference here at Daytona was that if Cooley couldn’t win, then another of the four Yoshimura R&D of America Suzuki GS1000 Superbikes entered (ridden by Cooley, Ron Pierce, David Emde and Roberto Pietri) was certain to cross the line first.

When Cooley pitted, the Yoshimura bikes were running first, second, third and fifth. A few laps later Yoshimura Suzukis were first through fourth. Pops Yoshimura and company owned Daytona.

That doesn’t mean they didn’t have problems. They seized engines early in the week before discovering that the gas tank cap vents were plugged on two of the bikes. They bent valves, once because Ron Pierce missed a shift in practice just hours before the heat races, twice because the Kawasaki cam chain idler sprockets fitted into the Suzuki cylinder heads came apart on the long Daytona straights early in the week. The problem hadn’t shown up on the dyno or at other racetracks, but Daytona’s length allowed the Superbikes to reach incredible speeds (Cooley’s bike was clocked at 167 mph at one point, 8 mph faster than the Yoshimura Suzuki that won here in 1978, 12 faster mph than the fastest bike entered in 1977 and 17 mph faster than the bike that won in 1977) punctuated by violent deceleration and rapid downshifts at the infield entrance and back straight chicane. The cure was to replace rubber vibration-damping bushings in the roller assemblies with bronze bushings obtained from a local machine shop.

Not all the problems were mechanical. Emde crashed in his 250cc Expert heat race when his TZ250 seized and was rushed to the infield hospital. He was released, but began spitting blood on the walk back to the pits before the Superbike heats. Back in the hospital for examination, he missed the heat race; if he started the final at all, it would be in last place, number 63 on the grid.

Pierce won his heat race by 41 seconds (Cooley won his by 30 seconds, with Pietri second) but set off a controversy with his starting method. AMA rules stipulate that a rider cannot creep past his individual grid starting line more than half a bike length before being docked a lap. Knowing that, and wanting to take full advantage of the rules, Pierce staged with his feet planted firmly on his line. Meanwhile, an unnamed AMA official told the riders to move back one half length behind their lines.

Pierce didn’t move, took the heat race lead from Reg Pridmore before half a lap had passed, and pulled away to win while Pridmore’s Vetter Kawasaki blew up (for the second time) with a seized number three cylinder. The AMA line judge docked Pierce a lap, and the politics hit the fan. AMA officials were not sympathetic to Pierce’s plight, and declined to throw out the penalty on the basis of good sense. But Pierce, knowing the rulebook well, came up with a technicality—the rules require that each row of starting lines on the grid be exactly 25 ft. apart. Were they at Daytona? A tape measure revealed a distance of 23 ft. The AMA, caught by their own rules, relented. Pierce’s penalty (and one imposed on Skip Aksland in his 250cc heat) was lifted, and Pierce was restored to his front-row Superbike final race starting position.

Pierce’s political problems weren’t over yet. Earlier in the week the entire Yoshimura team had switched from Michelin tires to Goodyear slicks—the Goodyears simply worked better. But Pierce, eager for an advantage, decided shortly before the race to exchange the recommended D1705 for a softer compound D1829 slick on the rear of his Suzuki, despite fears expressed by Goodyear technicians that the softer tire wouldn’t last the 100 miles of the extended Superbike final (previous Superbike races were 50 miles). When Pierce appeared at the pit gate to scuff in his new tires during the last practice before the race start, officials wouldn’t let him out, citing a rule banning clubman handlebars—the bars couldn’t be lower than their mounts, said the AMA, despite the fact that some bikes, such as Ducati Desmos, are allowed to run clip-ons. Pierce’s mechanics frantically changed handlebars, but by the time they were finished, practice was over. Pierce would have to start on un-scuffed slicks.

There had been much talk prior to Daytona that other tuners had mined huge horsepower finds to threaten Yoshimura dominance of the Superbike Racing. But> when it came down to lap times and racing, there were no threats. The only rider able to compete with the Yoshimura team probably would have been Mike Baldwin, riding a Yoshimura-chassied Kawasaki Motors Corp. KZ1000 Mk. II with Yoshimura parts in the engine. But Baldwin crashed his KR750 hard in practice between the 250cc heat races and the Superbike heat races. He rode one lap of the Superbike heat to qualify for the final, but doctors feared that he had dislocated his shoulder and had broken his wrist and collarbone. Baldwin didn’t grid for the final.

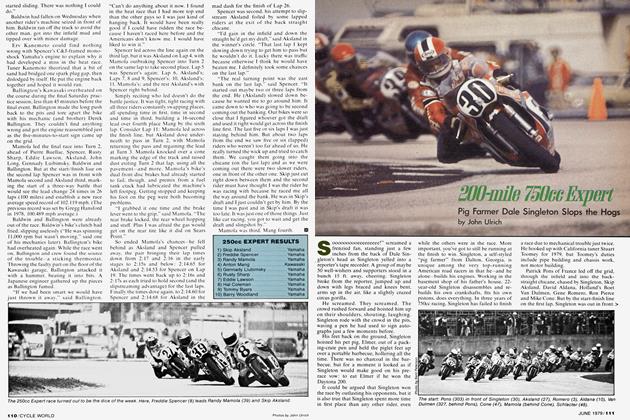

So it was Cooley’s start. Pierce and Pietri went back and forth for second until Pierce decided his tires were scuffed in enough and took off. Steve McLaughlin was fourth until his Racecrafter Kawasaki’s gas cap popped open and he stopped to secure it. By the second lap Cooley had seven seconds on Pierce with Pietri an additional 18 seconds behind Pierce. Fast Freddie Spencer on an exotic Ducati prepared by Reno Leoni was fourth, three seconds back. Emde, who had started 63rd, was already ninth—he had been 21st at the end of the first lap.

On lap four Cooley and Pierce were already lapping backmarkers, one of whom forced Pierce off his line at Turn 3. That set up Pierce too close inside for Turn 4, and the sound of his bike’s engine rpm soaring as the rear tire lit up and spun at the turn apex snapped spectators’ heads around to see an incredible sight—Pierce, full lock, right boot, ankle and calf the only thing between the side of the motorcycle and the pavement, apparently in the process of crashing. “It completely took off out from underneath me,” said Pierce later. “It hit the ground on the side and slid along a couple of feet and then caught and stood right back up again. It was an incredible feeling.”

Saved, Pierce waved to the crowd and continued on his way. By the eighth lap, Cooley knew he had a problem. “The brake lever started going in farther and farther toward the grip. It was almost like the pads had worn out of the thing completely in those eight laps. I could almost go into my regular braking points but would have to pump it a couple of times to get any lever out of it. It was still almost going all the way to the grip, but I could get it stopped a little bit.” Cooley’s bike was the only Yoshimura Suzuki fitted with RG500 discs and Tokico calipers. The others ran Lockheeds.

Cooley had run 2:13 the first lap, 2:11 the second, 2:12 the third and fourth, then slowed to 2:14, 2:13.6, 2:13.4, and 2:14 on the lap he discovered his brake problems. Most amazing was the fact that Cooley turned a 2:11 on the ninth lap, apparently spurred by the fear that this problem—any problem—was going to steal his win.

Meanwhile, Pierce, turning consistent 2:13s after his tires had scuffed in, caught sight of Cooley in the laps before the gas stops.

“I had been very easy on my machine,” said Pierce afterward, “shifting it about 500 rpm lower than I was told to and just kind of pacing myself. Then as soon as I got Wes in sight I kicked it up to 10,000 rpm instead of 9500 like I had been running. My engine was very fresh and my brakes were fresh and I just took off.” Cooley’s times drifted up to high 13s; Pierce’s dropped to low 13s and high 12s.

Cooley and Pierce pitted on the same lap, and exiting the pit row Cooley had about eight seconds on Pierce. “I came around going into the chicane on the 14th lap and got to my normal braking spot. I was pumping it up and just kept pumping the thing and there was no brake lever at all, no brakes at all and I started using the gears to get the thing stopped and I just couldn’t make the chicane and I went straight.” It took Cooley 30 seconds to get turned around inside the haybales of the chicane run-off path and back on course. Pierce had the lead and Cooley nursed his way around in second, turning low 14s, then high 14s, low 15s, high 15s, low 16s, finally a 2:15.6 finish lap. Emde had secured third, no one close ahead or close behind. Pietri had his hands full fighting off the advances of Spencer and John Long. Long used his GS Performance Group BMW’s large tank to skip the gas stop almost everyone else needed and thus join the fight for fourth going on between Spencer and Pietri—Pietri doing an admirable job of holding the two others at bay.

Spencer and Pietri retired almost simultaneously, Spencer’s Ducati shearing off its countershaft splines, Pietri’s Suzuki grinding its rear sprocket to death and throwing the chain. Pietri, a paying customer of Yoshimura’s racing services, had elected not to replace the sprockets and chain before the final. (The Yoshimura Team bikes are always fitted with new sprockets and chain before final events).

Long was fourth. Harry Klinzmann fifth after a continuing dice with Reg Pridmore and John Bettencourt. Pridmore retired with a thrown chain. McLaughlin, who had worked back to eighth after his gas cap repair stop, retired after almost crashing in the chicane with a flat rear tire.

On the last lap, Pierce’s Suzuki sounded a little off song, missing as he accelerated off the infield turns and onto the banking. “The last lap it dropped about 1000 peak rpm and started missing real bad,” said Pierce after the finish. “But it held together. My luck was good.”

Back in the pits, Yoshimura mechanics saw that the No. 1 piston crown was black, while the others showed a healthy grey/ brown color. That cylinder’s exhaust valve spring was broken. 13

DAYTONA SUPERBIKE RESULTS