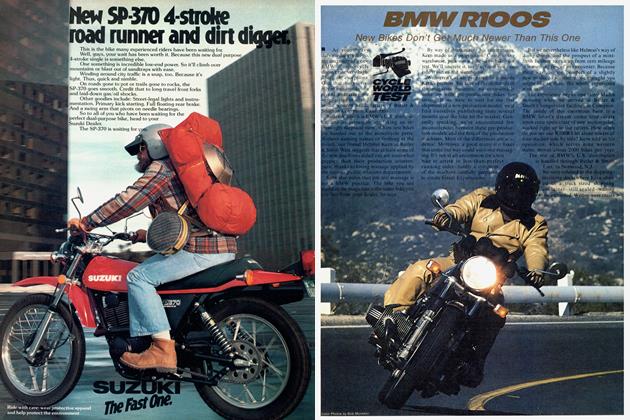

KAWASAKI KZ750

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Technology Catches Up To The Vertical Twin (With Surprising Results)

In this age of bigger and faster motor-cycles with more and more cylinders and valves and carburetors, there remains a market for traditionally-sized twin cylinder bikes. The subject of this test—the double-overhead-cam, balancer-equipped vertical-twin four-stroke KZ750— is Kawasaki’s fourth largest seller in spite of its relatively recent introduction in 1976. Every KZ750 made has been sold.

Some advantages offered by a traditional Twin are obvious: two spark plugs cost less than four or six: four valves are easier to adjust than eight or 24; two carburetors require less time to synchronize than four or six; two cylinders are narrower than four or six, and gulp less gasoline as well; and Twins, with fewer moving parts, generally w'eigh and cost less than equal-displacement multis. Another advantage is less obvious: Tw ins wear out tires and chains less frequently than multis, an advantage tied to a disadvantage— Twins usually make less horsepower than equally-sized multis.

In many ways, the KZ750 fits the stereotype of a Twin w hen compared to multis. But with dual overhead cams, replaceable-shim valve adjustment and twin balancer shafts, the KZ750 engine is far removed from the simple, pushrod British powerplants that first made 650 and 750class vertical Twins popular decades ago. It’s even more complicated than the 1970 vintage Yamaha XS650. which has a single overhead cam. adjustable valve tappets and no balancers. The question is. has the extra technology improved the breed?

In terms of speed, no. The KZ750 charges dowm the dragstrip in 14.12 seconds versus 13.86 seconds for the 1978 Triumph Bonneville 750. (It should be noted that the Bonneville requires premium gasoline and delivers about 10 fewer miles per gallon.) For comparison, the Kawasaki KZ650 Four does the standingstart quarter in 13.19 seconds; the Suzuki GS750 Four in 12.83 seconds.

One thing the modern touches do add is weight—at 506 lbs the KZ750 weighs 81 pounds more than the Bonneville (425 lbs) and 13 pounds more than the standard KZ650 Four (493 lbs). Another result of the technology is that maintenance is more complicated. The shim-and-bucket valve adjustment system has proven reliable in years of use in Kawasaki. Suzuki and Yamaha engines, and often requires attention at less frequent intervals than a traditional adjustable tappet design. But w'hen adjustment is called for, a set of assorted-size shims and a special bucket-depressing tool are needed. However, w ith one set of contact points, the bike’s timing is easier to adjust than that of the Bonneville, the Yamaha XS650 and some multis, excepting certain Yamaha and Honda models with pointless, electronic ignition systems.

Some equate double overhead camshafts with very high rpm and a cammy powerband. Yet the KZ750 engine delivers excellent low and mid-range torque, just as tradition says a Twin should. Tradition also has it that vertical Twins vibrate. In spite of two counter-weighted balancer shafts driven off the crankshaft, the KZ750 engine still shakes, but not nearly as much as the Bonneville. Certain Twin fanciers hold dear the idea that the low intensity reciprocation of a Twin is less bothersome than the higher-pitched massage of a Triple or in-line Four. Different people view' vibration differently, and some may even enjoy what others cannot tolerate. Be that as it may, no one could call the KZ750 smooth or its periodic motion pleasant. It may be that the balancers do more to change the character of the vibration in certain rpm ranges than to subdue it, but even rubber-mounted handlebars can’t always isolate the rearview mirrors and the rider's hands from the pulsing. Hard rubber grips don’t do anything to improve the rider’s comfort.

Below 4000 rpm, the shaking isn't bad. It's easy to cruise around town and cut through traffic wfithout exceeding that engine speed. The bike will shoot away from a stop at 1500-2000 rpm and cruise at 45 mph in fifth gear (2800 rpm) without complaint. At that speed, the left mirror is perfectly clear, the right mirror almost clear, and the overall vibration level almost nil. The engine is perfectly content to operate between 3000 and 3500 rpm as the rider shifts up through the gears, without jerking or detonating, and the mellowelongated exhaust note at those engine speeds sounds neat. The KZ750 has little drive line snatch when the chain is properly adjusted, so it’s possible to run the engine at lowrpm without lurching. The KZ750’s constant-velocity carburetors react more progressively to small twfist grip movements than the constant-velocity carbs used on some bikes, avoiding lurchinducing overreactions. The KZ750’s carburetor return springs do their job. yet don’t require enough force at the twist grip to tire the rider’s right wrist or shoulder.

Ridden around town at less than 4000 rpm. then, the KZ750 is fine, an enjoyable mount. But head up an expressway onramp. grab a handful and feel the commotion! When the tach needle passes 5000 rpm. the buzzing in the footpegs, bars and ;senger pegs spreads to the seat and gets lous. And by the time the rpm reaches )0. both mirrors pivot outward on their 1 mounts from the sheer intensity of the ration. At the 7750 rpm redline. it feels if the whole machine will shake itself from under the pilot. After the rider ks the rpm down to about 4200—an indicated 65 mph—and re-adjusts the mirrors, he realizes that the KZ750 is still chugging down the road, immune to the force of its own redline trembling. It may feel as if high-rpm running will rattle the bike into oblivion, but that doesn’t mean it actually will.

At highway speeds, the mirror images

remain slightly blurred and the buzzir continues through the bars, passenger pe, and—somewhat subdued-^the footpeg It’s still far less shaking than experience on a Bonneville. In fact, the KZ750 is T smoothest—if the word applies—large ve tical Twin available today. How muc vibration is too much vibration is a subje< tive judgment, and test riders noted that their state of mind at a given moment greatly affected their tolerance. But at least one tester, after riding the KZ750 100 high-speed Interstate miles while suffering a severe sinus attack, staggered back into the office and declared that the KZ750’s handlebars had increased to two inches in diameter.

The seat slopes stylishly upward in the rear, and after half an hour on the road, that is more noticeable than the constant, steady, low-level throbbing. The seat sends the rider sliding slowly forward towards the gas tank, bunching up trousers uncomfortably in the crotch.

The front forks and the rear shocks lack the ability to react to concrete pavement expansion joints and other small bumps. Only larger jolts will move the suspension, even when shock spring preload is set at the lowest position.

Once the shock preload is set at the maximum, the bike remains steady even when run hard down twisty roads. Handling and braking are flawless at anything close to sane street speeds. Even the hardest charge through sweeping turns doesn’t produce a wobble. Ground clearance is adequate, and only the center stand touches in tighter turns. The single disc brakes at each end are strong and progressive. and the rear disc is one of the most controllable we’ve ever experienced. The KZ750’s rear brake doesn’t lock unexpectedly at turn entrances or when applied at low speeds.

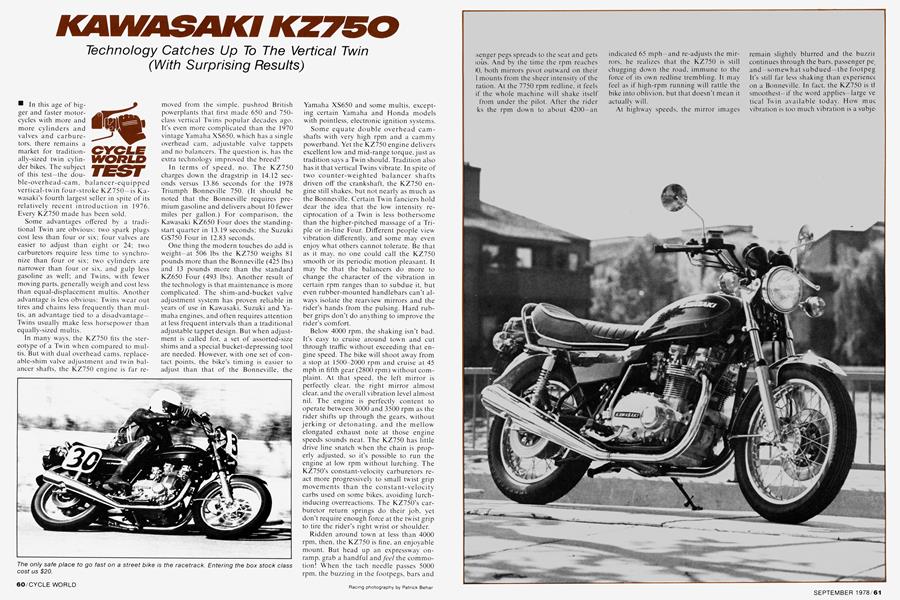

Fast street riding is a matter of bravery and foolishness—how fast the rider dares go in a hostile environment filled with errant motorists, stop signs, road debris, police, loose dogs and other hazards. The best and safest place to determine a motorcycle’s handling characteristics when pushed to the limits is a racetrack. So, we rode the KZ750 out to a Manning Racing club event at Ontario Motor Speedway and entered the box stock class. To pass tech inspection, it was necessary to safetywire the oil drain plug; remove the mirrors, centerstand and sidestand; disconnect the brake light; and tape the headlight, taillight and turn signal lenses. The bike was raced with unleaded gasoline, which Kawasaki recommends for street use.

Racetracks have a way of making things like vibration and rider comfort unimportant while magnifying the importance of handling and horsepower. The KZ750 delivered few surprises. With a good drive out of the last infield turn and the rider crouched in a mile tuck (left hand holding the left fork tube for decreased wind resistance), the KZ750 would indicate 110 mph at the end of the long straightaway, hopelessly slow for the open box stock class (some clubs break box stock divisions at 675cc to include the KZ650 with 1mm overbore). But at that speed, the KZ750 remained as steady and wobble-free in a straight line, around the banking and through the wide open infield esses as it was at slower street speeds.

The bike would wobble if the rider unloaded the frame by suddenly backing off the throttle in the middle of a highspeed turn—a manuever sometimes necessary when trying to pass or lap erratic riders and groups of riders. Pavement bumps in the middle of some flat, sweeping turns at speeds above 80 mph also started minor oscillations, especially at the apex, where the bike was leaned over the farthest.

Production motorcycle frames, swing arm assemblies, forks and wire wheels all have a certain amount of give, or flex. Cornering at high speeds generates forces sufficient to cause those components to load in one direction, generally toward the outside of the turn. Slamming the throttle shut—or hitting a bump that jolts the rear wheel even slightly off the ground—interrupts the driving force and can allow the loaded parts to snap back in the other direction. That starts an oscillation, or wobble. In the KZ750’s case, the wobble never got bad enough to endanger the rider.

Cornering speed and lean angle both were limited by the stock Bridgestone tires (Super Speed 21R2 and 21F2). At just about the point where the footpeg would drag on either side, the tires ran out of side tread. When that happened, any attempt to go through a given turn faster made the tires slip. As long as the rider remembered the limits of the stock tires, the situation wasn't a problem.

The front tire also limited braking performance on the racetrack. Diving into a 50-mph turn after a straightaway during practice, the front brake would easily lock the tire. It isn’t a case of the front brake not being progressive, it’s just that the tire runs out of traction before the brake runs out of power. The motorcycle could have stopped faster and cornered harder with a good set of performance tires (see the tire test in last month’s issue). With no extraordinary infield cornering or braking advantage, there was no way the rider could make up for the KZ750’s horsepower handicap. The results show fourth in the Open class, behind two KZlOOOs and one Ducati 900SS, and ahead of a GS1000 Suzuki with a novice rider.

Halfway through a six-lap race on the 3.19-mile Ontario long course, the KZ750 would no longer pull the redline in fourth gear, so the rider started shifting into fifth about 500 rpm before the redline. The bike’s indicated top speed at the end of the front straightaway fell from 110 at the start of the race to 100 after the mid-way point. Although maximum speed decreased as engine temperature increased during the event, after the finish the engine had used no detectable quantity of oil, and remained almost perfectly oil tight. A little oil seepage from the head gasket—at the front center of the cylinder/cylinder-head joint—had blown back on the first few cylinder cooling fins on each side. But that seepage was on the bike when first delivered for testing. It didn’t look like the slight bit of lubricant present on the fins had increased during the 36 miles of wide-open racetrack running represented by five practice and six racing laps.

Those 36 miles brought the average mileage for that tank of gas down to 35.2 miles per gallon, with the bike demanding reserve at 110 miles. More typical street and freeway use yielded averages of about 46 mpg , with reserve required at about 136 miles. On the Cycle World test route, which is used to obtain the mileage figures listed in each road test data panel, the KZ750 averaged about 53 mpg.

As expected, the KZ750’s controls and lights work well. Each control switch is located in a logical, easy-to-find location, but the Kawasaki has one switch most new machines lack—a working headlight/taillight on/cxff switch, located above the electric starter putton on the throttle assembly. Another unique Kawasaki gadget is a safety-motivated clutch-lever electric starter override. The KZ750’s electric starter won’t spin unless the clutch is pulled in, even if the transmission is in neutral. Kick starting is unaffected by the clutch lever position. Still another gadget, but one which is less effective, is the helmet lock located on the left side of the handlebars. Anybody with the proper-size Allen wrench can upbolt the “lock,” walk away with any attached helmets, and break apart the lock assembly elsewhere.

The tachometer, speedometer, resettable tripmeter and odometer are all easy to read, both day and night. Instrument needles are steady under all conditions, without any noticeable waver or wander. Unfortunately, the speedometer is wildly optimistic, indicating 60 mph when the machine is actually moving at 53.7 mph. Thus, the indicated top speed of 110 mph reached at Ontario was an actual 98.5 mph.

Speedometer error, certain idiosyncrasies—like the easy-thwart helmet lock and the usual Kawasaki quirk of having to remove the countershaft cover to change the oil filter—can’t alter a basic truth; The KZ750 is an inexpensive and durable 750cc motorcycle quite capable of moving a rider down the road, dependably and without losing oil and parts along the way. It isn’t fast; it isn’t quick; it is only smooth when compared to other big vertical twins and insuring it will cost more than insuring smaller and faster machines—like the KZ650 four—since most insurance companies up the rates at 750cc. But like other four-stroke Twins in its size range, the KZ750 offers certain advantages important to certain people. At $1895, it’s the least expensive 750 available, and a great buy. >

KAWASAKI KZ750

SPECIFICATIONS

$1899