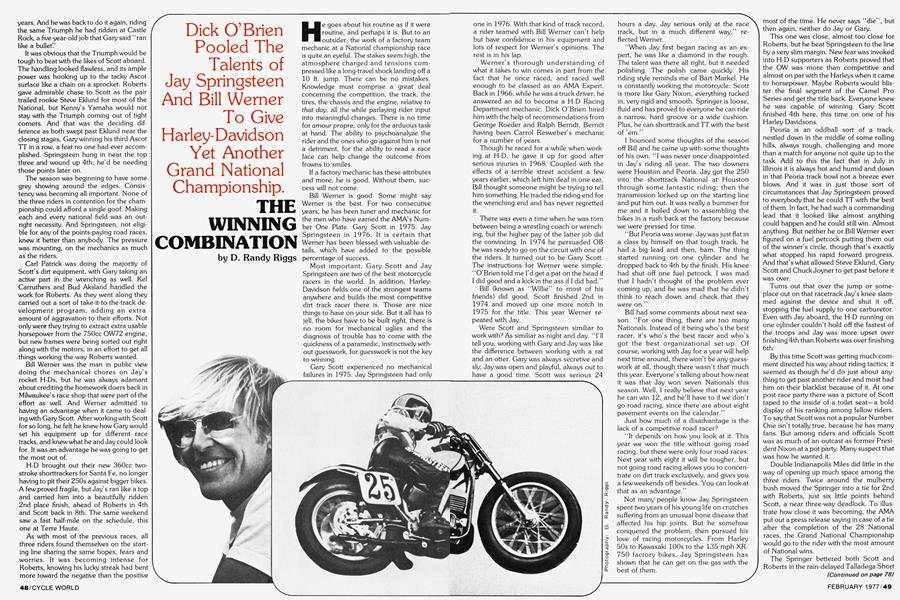

THE WINNING COMBINATION

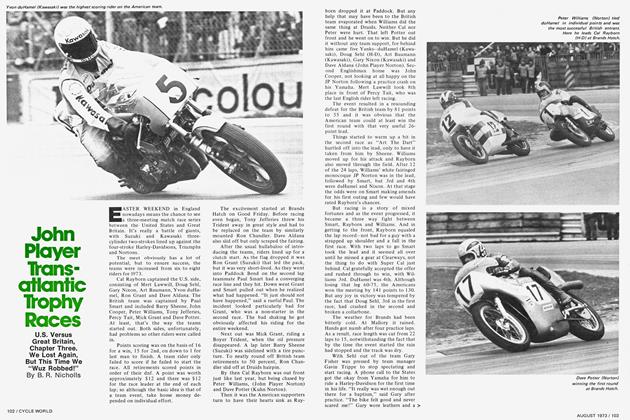

Dick O’Brien Pooled The Talents of Jay Springsteen And Bill Werner To Give Harley-Davidson Yet Another Grand National Championship.

D. Randy Riggs

He goes about his routine as if it were routine, and perhaps it is. But to an outsider, the work of a factory team mechanic at a National championship race is quite an eyeful. The stakes seem high, the atmosphere charged and tensions compressed like a long-travel shock landing off a 10 ft. jump. There can be no mistakes. Knowledge must comprise a great deal concerning the competition, the track, the tires, the chassis and the engine, relative to that day, all the while parlaying rider input into meaningful changes. There is no time for amour propre, only for the arduous task at hand. The ability to psychoanalyze the rider and the ones who go against him is not a detriment, for the ability to read a race face can help change the outcome from frowns to smiles.

If a factory mechanic has these attributes and more, he is good. Without them, success will not come.

Bill Werner is good. Some might say Werner is the best. For two consecutive years, he has been tuner and mechanic for the men who have earned the AMA’s Number One Plate. Gary Scott in 1975. Jay Springsteen in 1976. It is certain that Werner has been blessed with valuable details, which have added to the possible percentage of success.

Most important, Gary Scott and Jay Springsteen are two of the best motorcycle racers in the world. In addition, HarleyDavidson fields one of the strongest teams anywhere and builds the most competitive dirt track racer there is. Those are nice things to have on your side. But it all has to jell, the bikes have to be built right, there is no room for mechanical uglies and the diagnosis of trouble has to come with the quickness of a paramedic, instinctively without guesswork, for guesswork is not the key to winning.

Gary Scott experienced no mechanical failures in 1975. Jay Springsteen had only one in 1976. With that kind of track record, a rider teamed with Bill Werner can’t help but have confidence in his equipment and lots of respect for Werner’s opinions. The rest is in his lap.

Werner’s thorough understanding of what it takes to win comes in part from the fact that he once raced, and raced well enough to be classed as an AMA Expert. Back in 1966, while he was a truck driver, he answered an ad to become a H-D Racing Department mechanic. Dick O’Brien hired him with the help of recommendations from George Roeder and Ralph Berndt, Berndt having been Carrol Resweber’s mechanic for a number of years.

Though he raced for a while when working at H-D, he gave it up for good after serious injuries in 1968. Coupled with the effects of a terrible street accident a few years earlier, which left him deaf in one ear, Bill thought someone might be trying to tell him something. He traded the riding end for the wrenching end and has never regretted it.

There was even a time when he was torn between being a wrestling coach or wrenching, but the higher pay of the latter job did the convincing. In 1974 he persuaded OB he was ready to go on the circuit with one of the riders. It turned out to be Gary Scott. The instructions for Werner were simple. “O’Brien told me I’d get a pat on the head if I did good and a kick in the ass if I did bad.”

Bill (known as “Willie” to most of his friends) did good. Scott finished 2nd in 1974 and moved up one more notch in 1975 for the title. This year Werner repeated with Jay.

Were Scott and Springsteen similiar to work with? As similiar as night and day. “I’ll tell you, working with Gary and Jay was like the difference between working with a rat and an otter. Gary was always secretive and sly; Jay was open and playful, always out to have a good time. Scott was serious 24 hours a day, Jay serious only at the race track, but in a much different way,” reflected Werner.

“When Jay first began racing as an expert, he was like a diamond in the rough. The talent was there all right, but it needed polishing. The polish came quickly. His riding style reminds me of Bart Markel. He is constantly working the motorcycle. Scott is more like Gary Nixon, everything tucked in, very rigid and smooth. Springer is loose, fluid and has proved to everyone he can ride a narrow, hard groove or a wide cushion. Plus, he can shorttrack and TT with the best of ’em.”

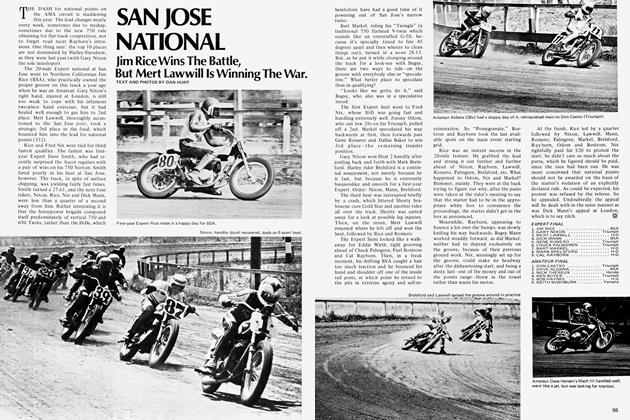

I bounced some thoughts of the season off Bill and he came up with some thoughts of his own. “I was never once disappointed in Jay’s riding all year. The two downers were Houston and Peoria. Jay got the 250 into the shorttrack National at Houston through some fantastic riding; then the transmission locked up on the starting line and put him out. It was really a bummer for me and it boiled down to assembling the bikes in a rush back at the factory because we were pressed for time.

“But Peoria was worse. Jay was just flat in a class by himself on that tough track, he had a big lead and then, bam. The thing started running on one cylinder and he dropped back to 4th by the finish. His knee had shut off one fuel petcock. I was mad that I hadn’t thought of the problem ever coming up, and he was mad that he didn’t think to reach down and check that they were on.”

Bill had some comments about next season. “For one thing, there are too many Nationals. Instead of it being who’s the best racer, it’s who’s the best racer and who’s got the best organizational set-up. Of course, working with Jay for a year will help next time around, there won’t be any guesswork at all, though there wasn’t that' much this year. Everyone’s talking about how neat it was that Jay won seven Nationals this season. Well, I really believe that next year he can win 12, and he’ll have to if we don’t go road racing, since there are about eight pavement events on the calendar.”

Just how much of a disadvantage is the lack of a competitive road racer?

“It depends on how you look at it. This year we won the title without going road racing, but there were only four road races. Next year with eight it will be tougher, but not going road racing allows you to concentrate on dirt track exclusively, and gives you a few weekends off besides. You can look at that as an advantage.”

Not many people know Jay Springsteen spent two years of his young life on crutches suffering from an unusual bone disease that affected his hip joints. But he somehow conquered the problem, then pursued his love of racing motorcycles. From Harley 50s to Kawasaki 100s to the 135 mph XR750 factory bikes, Jay Springsteen has shown that he can get on the gas with the best of them.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

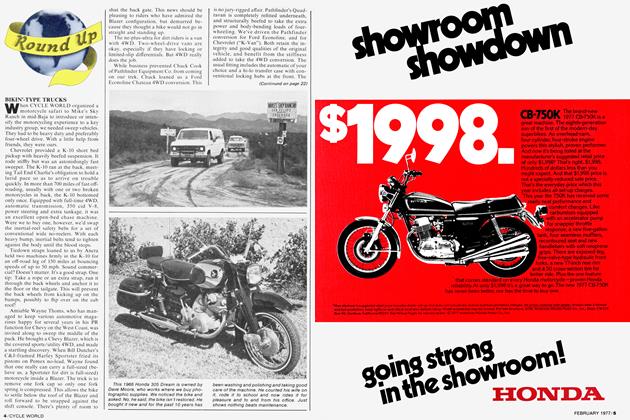

DepartmentsRound Up

February 1977 -

Letters

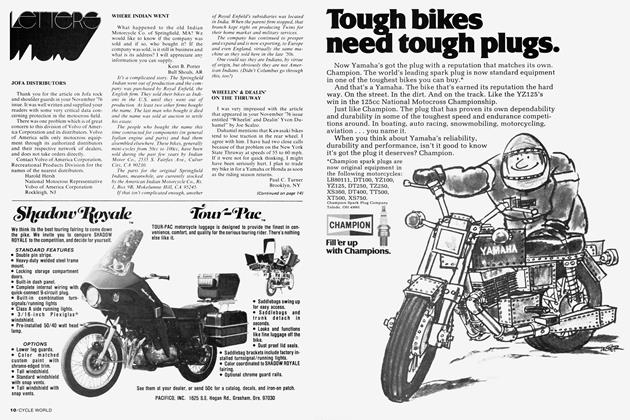

LettersLetters

February 1977 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

February 1977 -

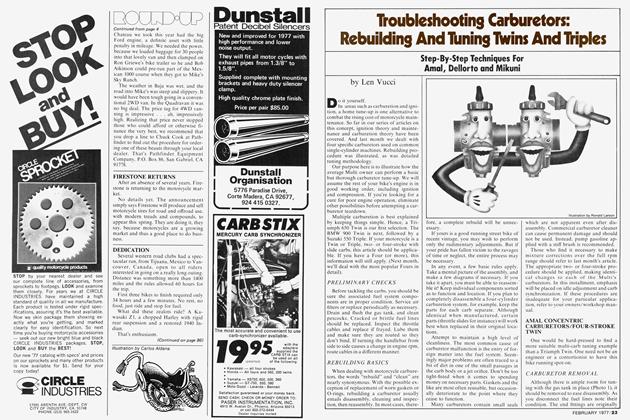

Technical

TechnicalTroubleshooting Carburetors: Rebuilding And Tuning Twins And Triples

February 1977 By Len Vucci -

Competition

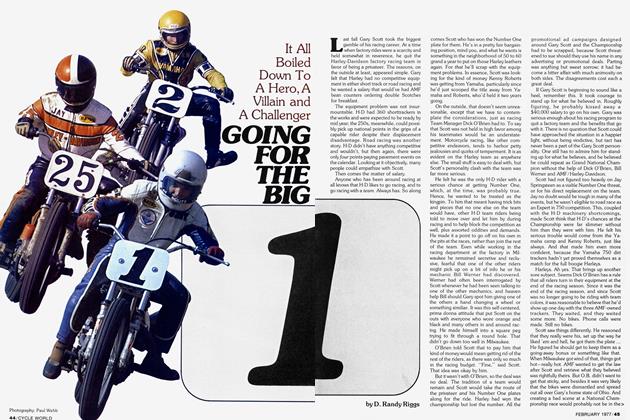

CompetitionGoing For the Big 1

February 1977 By D. Randy Riggs -

Features

FeaturesAn Off-Color Guide To Daytona Speed Week

February 1977 By D. Randy Riggs