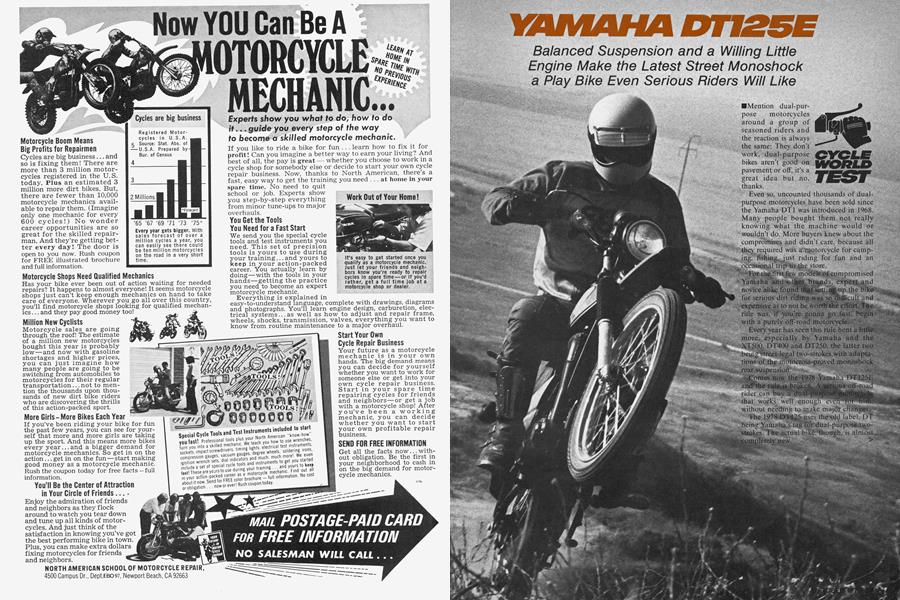

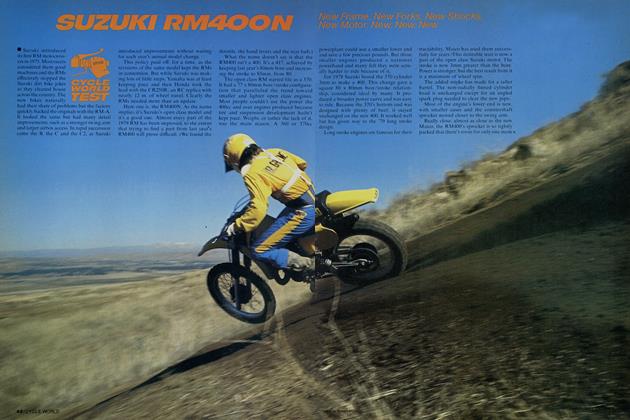

YAMAHA DT125E

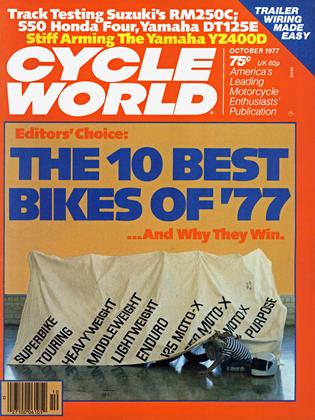

CYCLE WORLD TEST

Balanced Suspension and a Willing Little Engine Make the Latest Street Monoshock a Play Bike Even Serious Riders Will Like

Mention dual-purpose motorcycles around a group of seasoned riders and the reaction is always the same: They don’t work, dual-purpose bikes aren’t good on pavement or off, it’s a great idea but no, thanks.

Even so, uncounted thousands of dual-purpose motorcycles have been sold since the Yamaha DT1 was introduced in 1968. Many people bought them not really knowing what the machine would or wouldn’t do. More buyers knew about the compromises and didn’t care, because all they required was a motorcycle for camping, fishing, just riding for fun and an occasional trip to the store.

For the first few models of compromised Yamaha and other brands, expert and novice alike found that setting up the bike for serious dirt riding was so difficult and expensive as to not be worth the effiort. The rule was, if you're gonna go IL hegiT~ with a purel~ off-road niotorccle~ Ever~ sear has seen this rule bent a little more. especially by Yamaha and the X115 , 1) [`400 and 1)1 250, the latter two ct-legal two-strokes ith adapta tions ot thy. niOto~ross-pruved monoshock

rider can buv ñ! tor that works c1t enou"g~ ev WithOut needing to akc rnaj~ cha~~s. he 7~u~es the 1d label. D~ being~ama1~s ta~ for dua `-purpose o `~e r~i& b~. Tho is almos~ >

Begin with the frame, naturally subjected to radical rework to allow for monoshock suspension. The frame is of mild steel, with a large backbone shaped around the DeCarbon shock and spring unit. The front downtube is a single unit until just above the exhaust port, where it splits and forms a double cradle for the engine, just like a factory CZ, incidentally. The twin lower tubes turn upward just aft of the engine and join the backbone again below the fuel tank. The rear downtubes begin just behind the swing arm pivot and run backward and up to meet the top rail tubes, which start at the backbone and terminate behind the seat. All this provides a triangle below the seat, where all the various twisting and flexing forces come together. The swing arm is a double wishbone, with the lower fork pivoting on the frame and the upper fork connected to the monoshock. There are braces between the two forks, making another triangle, and the brackets and joints are carefully gusseted, again to resist flexing and twisting.

The monoshock unit is basically an economy version of the one used on the YZ-series motocross bikes. The design was developed by Dr. DeCarbon and uses pressured nitrogen working with but separated from the damping fluid. This second generation monoshock is lighter and more compact and more reliable than the originals. Good equipment.

In the DT application the monoshock is fitted minus the adjustable damping used on YZ shocks. That’s understandable, for cost if nothing else. Yamaha engineers apparently thought they could design a damping curve which would work with most riders under conditions to which the DT will be subjected. (As it turns out, they were right.)

A surprise, though, when the test DT 125 went into our shop. The factory lists rear wheel travel as 5.7 in. We came up with a maximum travel of 4 in., including some compression of the rubber snubber. Puzzling, although as we’ll see shortly, this wheel travel question seldom arises in real life.

Front forks are, well, perhaps a bit behind the times in that the front axle mounts at the center of the sliders rather than in front, the way all the hot motocross models now do. Travel is 6.8 in., moderate as these things go now. More important, the forks have been valved and sprung to match the bike’s weight and intended use. They are thus modern and sulfer not at all from being not exactly motocross style.

Stock tires are of course trials type, a good choice for most any dual-purpose motorcycle and fitted to all DTs by the factory because some states don’t allow knobbies on the road. Rims are steel. The spokes appear and act adequate or better; many hours in the rough didn’t knock them out of true. Conical hubs front and rear save some weight.

The DT125 uses a refined version of Yamaha’s road-going 125cc engine. For this version the engine cases have been reshaped into a narrower package, extra fins in a radial pattern have been added to the cylinder head. There’s a new aluminum cover for the clutch and a plastic cover for the oil injector and alternator. The exhaust pipe has been carefully routed in and around the frame, to the extent of using rubber packing where the pipe comes through the frame and rear fender, the better to not rattle. The 24mm Mikuni has a push-pull choke mounted on the carb body, so you always know how it works even if it’s sometimes awkward to reach. The cylinder porting and arrangement of the reed valve have been done to promote smooth delivery and a strong powerband, mostly at the bottom of the rev scale, where it should be in a play bike.

The transmission now has a sixth speed. Makes a lot of difference. First gear can be low enough to crawl across rocks and make brisk starts in traffic while the gears in between can provide for most trail work and sixth is there for the smooth and flat or the open road. The generous oil tank lives behind a cover below the fuel tank and is made of white, translucent plastic, so you can check the oil level simply by pulling off the panel and taking a look. As a fail-safe, there's also an oil level warning light on the dash. It lights up when the oil is low, or—to watch the watchman, so to speak—when the gear box is in neutral. That’s so you know the light is working. Seems like almost too much attention has been paid to this until one reflects that the alternative could be trying to ride home on straight gasoline.

Other impressive areas include a new starting lever that folds well out of the way, the flexible rear turn signal stalks we’ve seen on other dual-purpose Yamahas, a narrow and generous (for the engine’s displacement) fuel tank, a new seat with more padding and a more comfort than the seat on previous DTs. Incoming air is> filtered through oil-wetted foam in a box sealed against water, the tool kit even contains a spanner to adjust the spring preload on the monoshock . . . forgot to say that motocross feature is supplied with the DT monoshock also. Just about the only feature used on new road-only Yamahas and not used on the DT series is selfcanceling turn signals. For the price, and for the intended usage of the DTs, that omission can be accepted.

YAMAHA DT125E

$739

Forks on the dual-purpose DT are exceptional as their performance is more than adequate in virtually all situations, on-or off-road. Considering the bike’s price and intended application, these moderate-travel straight-leg forks are ideal.

Measured rear wheel travel is less than the 5.7 inches claimed by Yamaha, but seems to be adequate for the bike’s potential. Although lacking the adjustable damping feature of its bigger brothers, the 125’s rates should draw little, if any, criticism.

Tests performed at Number One Products

Another omission which actually isn’t, is the lack of passenger pegs and grab strap. Yamaha does not think the DT125 should be ridden by two people so they leave off provision for a passenger. As well they should. The bike is plainly too small for double duty.

Note: Also announced as Yamaha’s first 1978 models is the DT175E. As you’d guess the DTI75 has the larger engine and more power. It comes with CDI ignition while the 125 has plain of points and coil, and the 175 is as bright a blue as the 125 is bright green. Other than that and a few pounds, the 125 and 175 are the same.

How does the DT125E work? Nicely, under almost all conditions.

Begin with normal city riding. The DT125 fires easily, usually on the first kick. It’ll warm quickly; say maybe one minute at a fast idle and the choke can be pushed off. (Better do it that way rather than riding away, because pushing the little button tucked down there on the carb can be more awkward than the rider needs in traffic.)

Power is fine. Just about average for a 125 two-stroke, meaning while you won’t win drag races with anything wearing fewer than 18 wheels, neither will you feel the hot breath of cars on the back of your neck. First is low enough for good starts and the intermediate gears will get you up to speed and 6th will keep the DT ahead of the rush. The engine’s powerband is more like a power plateau, in that the engine is willing to pull strongly and cleanly from idle up to maybe 7000 rpm. The tachometer and the factory say the engine is redlined at 8 thou: They are optimistic. The engine will turn 8000 but the delivered power takes a distinct dive over 7 and shifting at 7000 proved the quicker way to gain speed.

The wheelbase, handlebar width and height, peg location et al are based on the reasonable expectation of riders ranging from the teens up to women of average size and men perhaps shorter and lighter than average, this in keeping with the engine’s displacement. On the road the DT125 accommodated most of the staff in comfort, albeit few of the test riders are larger than average. A 6-footer will have his knees in the air, a 10-year-old (off-road, of course) will need to stretch. But any and all will fit.

The DT125’s light weight gives agility and once again we learn that motorcycles with off-road geometry and controls and ground clearance are great sport on the pavement, up to the limits of the trials tires. (Which did not like rain grooves at all.)

Brakes worked fine. They are not large. They are not discs. Never mind. The bike is light and balanced and stops at the test track and on public roads were short and controlled. No compromise here.

On the open highway the DTI25 displays a stout heart and some limits. Actual top speed is 67 mph, well past the power peak, by the way and nearly into the red. Thanks to the meddlers with their 55 mph, the DT125 will actually keep up with the flow on the Interstate. The engine is spinning merrily away, the bars tingle, the mirrors buzz and the exhaust has a resonance that comes in right around the legal speed limit. The seat also seems to stiffen up when the rider is just sitting there. This combines into making Interstate touring on the DT125 something the owner will do because a stretch of highway is the most logical line between two good places to ride. For fun, no.

(The test miles-per-gallon figure of 72 should be noted with the understanding that the standard 100-mile test loop has 40 miles of Interstate. The first 20 on the DT125 seemed cruel and unusual so the test rider handled the return portion by heading across a secret stretch of dirt trails known only to him. He added 10 miles to the loop, returned a test figure on the optimistic side and had a terrific time, the slacker.)

Runners of errands and buyers who need the excuse of having a bike they can ride to work are well served.

Off-road is the best part.

The nearest competitors to the DT125’s method for serving two masters are its larger siblings, the DT250 and DT400. They have more power. They weigh more. The bigger motors go faster and while we were impressed by the 250 and 400 versions, still, their power and weight work against them in that more speed requires more stiffness and the DT250 and DT400 don’t begin to work well until they’re going faster than the trials tires like, and faster than the casual cowtrailer may wish to let himself in for.

The DT125 has none of this. Power is important for competition. For fun riding, power is that quality which gets you into the next corner sooner than you may expect. Or it gives the muscle to tackle hills better left to themselves.

The DT125 has enough engine and gears to handle anything the chassis will take. Meaning a pretty steep hill. And because the sheer speed is limited, bringing with it a limit in the length of jumps and the impact when the bike returns to earth, wheel travel is enough to do the job. As the pictures show, our Resident Rocket rode the DTI25 hard. At no time was he aware of the forks or monoshock hitting bottom. And the damping rate supplied by the factory was as close to right as any rate we’d choose if we had the option. The DT125 didn’t sag and the rear wheel didn’t send the bike pogo-ing into the air on downhill jumps, something we have encountered on the YZ series.

One secret: tire pressure. With the tires pumped for the street, they lose grip on the dirt. But by letting both tires down to 8-10 psi, as low as we dared because of the risk of sharp rocks pinching the tubes, the contact area increased and the trials tires had enough traction to allow normal trail speeds. Only shortcoming was that on a tight turn with no berm we could bank the DT over until the tread was clear and the wheel was riding on the non-treaded sidewall, at which point the grip goes instantly away and corrections are called for.

That didn’t happen too often, mostly because the front end stuck so well that slides weren’t needed. Haul on the bars, bank moderately and around the DT went.

The brakes performed well but not quite as well off-road as on. The power provided to grip a tractive surface works against the DT in dirt and sand. The front can be modulated, but the rear wheel tended to lock, especially on downhills. Careful is all you need.

Riding the DT125 in the wilderness turned up some surprised purists. The bike won’t win any races and for the record, the rider who’ll only ride off-road and has the means to haul a motorcycle there and back probably won’t like even this dual-purpose bike.

But the DT125 is a machine on which the serious rider can have fun and the fun rider can do more than he knows he can do. E9

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontOn Messing About With Motorcycles

October 1977 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1977 -

Departments

DepartmentsService

October 1977 By Len Vucci -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

October 1977 -

Competition

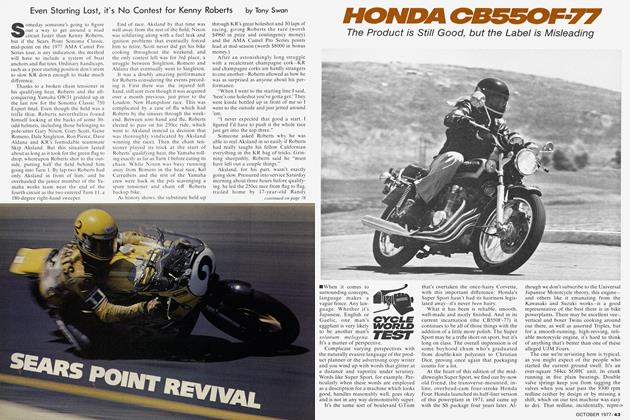

CompetitionSears Point Revival

October 1977 By Tony Swan -

Competition

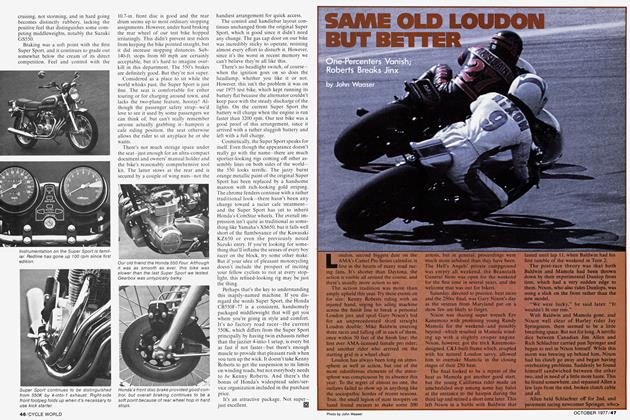

CompetitionSame Old Loudon But Better

October 1977 By John Waaser