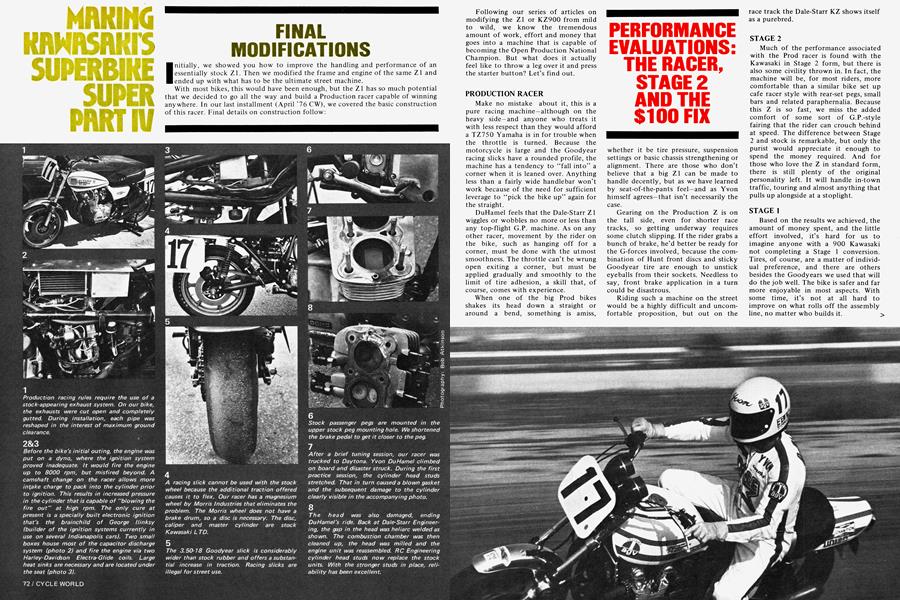

MAKING KAWASAKI'S SUPERBIKE SUPER PART IV

FINAL MODIFICATIONS

Initially, we showed you how to improve the handling and performance of an essentially stock Z1. Then we modified the frame and engine of the same Z1 and ended up with what has to be the ultimate street machine.

With most bikes, this would have been enough, but the Zl has so much potential that we decided to go all the way and build a Production racer capable of winning anywhere. In our last installment (April ’76 CW), we covered the basic construction of this racer. Final details on construction follow:

Following our series of articles on modifying the Zl or KZ900 from mild to wild, we know the tremendous amount of work, effort and money that goes into a machine that is capable of becoming the Open Production National Champion. But what does it actually feel like to throw a leg over it and press the starter button? Let’s find out.

PRODUCTION RACER

Make no mistake about it, this is a pure racing machine —although on the heavy side—and anyone who treats it with less respect than they would afford a TZ750 Yamaha is in for trouble when the throttle is turned. Because the motorcycle is large and the Goodyear racing slicks have a rounded profile, the machine has a tendency to “fall into” a corner when it is leaned over. Anything less than a fairly wide handlebar won’t work because of the need for sufficient leverage to “pick the bike up” again for the straight.

DuHamel feels that the Dale-Starr Zl wiggles or wobbles no more or less than any top-flight G.P. machine. As on any other racer, movement by the rider on the bike, such as hanging off for a corner, must be done with the utmost smoothness. The throttle can’t be wrung open exiting a corner, but must be applied gradually and smoothly to the limit of tire adhesion, a skill that, of course, comes with experience.

When one of the big Prod bikes shakes its head down a straight or around a bend, something is amiss, whether it be tire pressure, suspension settings or basic chassis strengthening or alignment. There are those who don't believe that a big Zi can be made to handle decently, but as we have learned by seat-of-the-pants feel-and as Yvon himself agrees-that isn't necessarily the case.

PERFORMANCE EVALUATIONS: THE RACER, STAGE 2 AND THE $100 FIX

Gearing on the Production Z is on the tall side, even for shorter race tracks, so getting underway requires some clutch slipping. If the rider grabs a bunch of brake, he’d better be ready for the G-forces involved, because the combination of Hunt front discs and sticky Goodyear tire are enough to unstick eyeballs from their sockets. Needless to say, front brake application in a turn could be disastrous.

Riding such a machine on the street would be a highly difficult and uncomfortable proposition, but out on the race track the Dale-Starr KZ shows itself as a purebred.

STAGE 2

Much of the performance associated with the Prod racer is found with the Kawasaki in Stage 2 form, but there is also some civility thrown in. In fact, the machine will be, for most riders, more comfortable than a similar bike set up cafe racer style with rear-set pegs, small bars and related paraphernalia. Because this Z is so fast, we miss the added comfort of some sort of G.P.-style fairing that the rider can crouch behind at speed. The difference between Stage 2 and stock is remarkable, but only the purist would appreciate it enough to spend the money required. And for those who love the Z in standard form, there is still plenty of the original personality left. It will handle in-town traffic, touring and almost anything that pulls up alongside at a stoplight.

STAGE 1

Based on the results we achieved, the amount of money spent, and the little effort involved, it’s hard for us to imagine anyone with a 900 Kawasaki not completing a Stage 1 conversion. Tires, of course, are a matter of individual preference, and there are others besides the Goodyears we used that will do the job well. The bike is safer and far more enjoyable in most aspects. With some time, it’s not at all hard to improve on what rolls off the assembly line, no matter who builds it. ;

Both the Stage 1 and Stage 2 versions of our Z1 project were designed to be totally street legal. After construction, each version was carefully broken in, then ridden to Irwindale Raceway for acceleration testing. Dale Alexander of Dale-Starr Engineering met us at the drag strip and jetted each version to insure maximum performance.

Both Stage 1 and Stage 2 bikes were tested with stock gearing (15/35) and a Goodyear MR 85 rear tire. We shifted the Stage 1 version at 9000 rpm (indicated redline) and came up with a quarter-mile time of 12.361 sec. Speed was 108.04 mph. Actual top speed on this machine turned out to be 126.63 mph at 8157 rpm. Top speed in this case was limited to power output, as redline rpm could not be reached.

Stage 2, or the ultimate street machine, is really impressive when compared to the essentially stock Stage 1. Quarter-mile time was reduced to 1 1.315 sec. with a trap speed of 121.62 mph. We experimented with shift points on this engine and ended up changing gears at 9000 rpm. Quarter-mile times could have been improved with a tire change but, for comparative purposes, we declined. Actual top speed at 10,020 rpm is 155.55 mph. This speed is unattainable at any drag strip facility and at most race tracks. You need a test area with a long, long straight and ample room for braking.

ACCELERATION AND TOP SPEED

We didn’t run the racer at the drag strip because of its close-ratio transmission (first gear is considerably taller than stock) and high overall gearing, but we can assure you that it accelerates even quicker than Stage 2 once underway.

Top speed on our racer depends on the overall gearing, which is altered by changing the rear sprocket. To give you a total picture, we figured it three ways: stock, geared for Ontario, and geared for Daytona. All gear combinations use a standard primary reduction ratio of 1.73:1. Fifth gear in the close-ratio transmission figures out to 1.26:1.

Standard gearing (15/35) @ 10,500 rpm = 158 mph. With this gear, top speed is limited by engine rpm, as there is an excess of horsepower available.

Ontario gearing (15/34) @ 10,500 rpm = 163 mph. The bike will attain this top speed if track conditions are optimal.

Daytona gearing (15/31) @ 10,500 rpm = 179 mph. This speed is probably not attainable during a race at Daytona because of the chicane in the backstretch. Without the chicane, who knows?

Even more impressive than these speeds is Dale-Starr Engineering’s racing record. There have been seven Open class Production races staged by the AMA. Our bike, and/or bikes identical to it, have won five of the races. ra

Next month we'll announce the winner of this bike and will hope fully be able to include an engine dyno chart on the racer.

PRODUCTION RACER

$5223

STAGE I & STAGE 2~

View Full Issue

View Full Issue