ROAD RIDING

DAN HUNT

TRAFFIC AND YOU

When I first set out to write about road riding, I had planned to give you the usual dose of stuff about the danger of riding close to car doors on city streets, avoiding grease spots and riding off the center of the lane, and using the automobile turning left ahead of you as a shield for your own left turn.

There, you have the dose, and that’s all you get, because I would rather not waste your time by writing about obvious things. I’d rather, instead, deal with a few interesting techniques and ways of seeing the traffic environment that will help you get it on in speedy fashion without putting your ass in a sling.

The motorcycling community has come up with all sorts of formulas for protecting you against the malevolent scourge of automotive traffic. “See and be seen” is one of the most commonly heard mottos. Its message is clear enough. Unfortunately, to see and be seen is inadequate taken by itself.

Traffic, a flow of hard metallic bodies that is only partially regulated, requires a feeling for physics, space, timing and psychology, as well as the careful use of vision.

Other people on the road have a curious way of regarding motorcycles. They may be nice folk and good citizens, but most of the time they perceive a motorcyclist and his machine as an inanimate object, rather than a human being with a personality and very mortal limitations when he comes into collision with hard objects.

This point was driven home to me in the only street accident I’ve had in 15 years of riding. A car turned sharply right as I was pulling off the road into a parking lot and we met at his right front fender.

Thus clobbered, I rebounded to the ground in pain and shock. As I sat there, my bike ticking over on idle on its side a few feet away, nothing happened. No people. Finally, the driver and his wife appeared at the front of their car, and looked at it for a moment. Then the driver approached, but strangely didn’t come closer than about five feet. He said, “Are you all right?” and immediately launched into all the reasons why he thought I shouldn’t have been there for him to hit. His wife sobbed, “Oh, I wish we’d never bought a small car!” She never came closer than about 20 feet, apparently unwilling to confront the human being behind the inanimate object that had just come into contact with the front end of her car. Trivia, that of what size car they owned, became her emotional fortress.

(Continued on page 92)

Continued from page 90

This kind of alienation is not directed at motorcyclists only. It also occurs automobile against automobile. But the size differential of these two types of transportation makes alienation a dangerous thing for the rider. The rider can do much to defend himself by attempting to demonstrate that the object aboard the small two-wheeled moving object is indeed a human being with human priorities.

How do you do it? Mainly by riding in the company of traffic in such a manner that you prove to all around that a human being is in control of the machine, and not vice versa.

A human being communicates to another human being by the use of symbols: words, hand gestures, motions, body language. He calls for attention by broadcasting all these things. The motorcyclist can do the same—often in subtle fashion.

I’ve developed my own repertoire of things to broadcast my humanity to surrounding traffic. Take, for instance, the standard hand signal. Many bikes today have directional signals. Because they are mechanical, and very close together due to the narrow profile of the motorcycle, most people don’t believe them. But the hand signal is hard to ignore. It’s the outstretched hand of a human being. And the gloved hand of a motorcyclist, like gloved hands throughout history, connotes a certain feeling of authority, a strong demand for recognition. When you really need to make a point to following or oncoming traffic, do it with your hand.

If you are in an ambiguous situation, you may do well to go beyond the usual left/right/stop signals required by law. Sometimes you can attract the attention of a motorist, then point to him where you desire to go. This is useful when changing lanes. Naturally, you should be sure that he has seen your signal. Establish eye contact with him. Look for the signs on his face that he has seen you and knows that you want to do something that requires his cooperation. I’ve found that once I establish eye contact, I encounter little aggressiveness or defiance from a motorist. In a line of city traffic, for example, motorists are reluctant to allow other cars to change lanes or move in front of them. Yet, if you establish eye contact and clearly “ask” for the space, most of these same hard-nosed people suddenly become passive and cooperative and go out of their way to fit you in smoothly.

In situations where eye contact and hand signals are difficult, you have to change your tactic. A typical situation is the intersection where you are approaching an oncoming car that has slowed for a left turn. Will he turn in front of you? Maybe he doesn’t see you.

The clue to his behavior is to put yourself in his shoes. He has stopped for the turn, or is slowing. He sees the oncoming car and knows he must stop. The motorcycle in place of the oncoming car is harder to see. It’s a narrow vertical image on his retina. But it has virtually no movement across his field of vision, because it is approaching almost straight on. It therefore becomes even more insignificant, and may be totally disregarded.

You can help overcome his limitation of perception only by causing a visual image to move sideways across his retina. And the only way you can do that is to move sideways yourself. So, as you approach an intersection with oncoming cars, make your machine zig-zag slightly in the lane. Or merely shift your weight back and forth to the side as the machine continues straight. It’s an unusual motion to see, and it is unmistakably human in nature, because it appears to be erratic rather than smooth and machine-like.

The same approach may be used when passing an automobile. A motorist seeing you from behind through his mirrors may not really recognize your presence and what it means. You are merely a dot on the glass. Thus you should two-stage your pass, first zigzagging slightly when in view of his inside mirror, and then zigzagging again as you move to the left and into view of his left outside mirror. You can be sure that you appear in his mirror when you can see his eyes reflected in the mirror. But you can’t be sure that he actually is using his mirror unless you zigzag and cause him to turn his eyes or his head.

Once alongside, you have only half the way to go. And you’re not in the clear. He can still move over into you. But you can go for double insurance at this point and gently move in and out on him in about the width of a foot to make sure that he’s aware of you. This, however, is an aggressive maneuver that could be interpreted as hostile; if you’re in so tight on him that you need to do that, chances are you shouldn’t be there in the first place; so, if you use it for self-defense, you should consider a wave of thanks once you’re past.

(Continued on page 94)

Continued from page 93

The above maneuvers could be called “safety wobbles.” They work because they cause movement on the retina of the eye, and then may be perceived. As the movement is erratic, rather than a continuous straight line, safety wobbles arouse both curiosity and, in some cases, minor anxiety in the eye of the beholder. If you need to establish eye contact, they’re great. Don’t be too wobbly, or it’s something else than the eyes you’ll be contacting.

Whenever you are involved with automobiles in an adjacent lane, or in a passing situation, you should always be aware of the driver, rather than just the car. Is he talking to a passenger? Lighting a cigarette? Looking around hesitantly like he’s lost and could change direction any minute? Fixing his gaze off at an angle like he’s spotted a driveway to be entered? Any one of these actions is a danger signal for you, a guarantee that his car is going to change its direction of travel.

Yet another concept to apply to your own direction, particularly on freeways or multi-lane city streets is that of spacing. Visualize an elliptical envelope surrounding you. It is about as wide as the lane you are riding in, but its length ahead and behind varies with the speed of the traffic around you. Develop a set of size standards for your own personal “envelope.” Whenever traffic encroaches upon that envelope or penetrates inside its boundaries, you should become immediately alert and ready to take evasive action. You may also use your imaginary envelope as a guide for passing in tight quarters. Whenever you switch lanes to pass, the risk becomes greater in proportion to the depth that cars in the new lane come into that envelope either in front or behind.

How long is the envelope? It varies. At freeway speed, the rear portion may be 140 to 160 feet, and the front 200 to 300 feet. Squirming through city streets at 20 mph, the envelope may shorten to 20 feet at the rear and 30 feet to the front. As you can see, the envelope concept is not based upon space alone, but is a concept of safety based upon time—time to stop, time to move out of the way, or even off the road.

Passing cars is not a sin, but it is sinful the way some people pass cars. The motorcyclist who really gets me is the one with all the safety gear, bright clothing, turn signals, crash bars, etc., who persists in hanging three or four feet off a motorist’s bumper prior to passing him on a narrow road. After five passing opportunities pass him by because the openings are too short in duration, he not only is frustrated, but has the attention of the other motorist and is irritating the hell out of him. Rather than bug a guy, I’d rather whoosh him.

To “whoosh” somebody is to time your pass so that your motorcycle is already traveling 20 mph faster than the car to be passed when you begin the pass. To do this, you have to pull back from the car rather than hanging on his bumper. If you already have traveled the road, you may know some prime passing places that are coming up. Just before they arrive, you’ve pulled back 50 to 100 feet behind the motorist. Seconds before the passing place comes up, you accelerate and, if the timing is right, the car ahead reveals a clear stretch of passing lane ahead just as you arrive near his rear bumper going a lotfaster than he is. If the stretch is not clear you slow down and start over again.

The intent of this kind of passing technique is to reduce passing time. The result is that you may use shorter stretches of passing lane. Consequently, on any given road, there are more places available to pass if you reduce passing time. This sandbagging technique may be used on unfamiliar roads as well as the roads on which you know every curve. You’ll find that once you get your timing down, the technique is not only faster from Point A to Point B, but it is also a lot less wearing on the nerves. Downhill on a windy road, it is a dream come true, because it adds gravity to engine power, to the speed and energy gathered in sand-bagging, and the sum of the three makes you feel like Godzilla Roberts, the invincible racer. Uphill, particularly so if you have a mediumdisplacement mount, carefully planned sandbagging is almost the only way you can get past quickly and safely when the traffic is heavy both ways. Remember, though, that “whooshing” a car ahead demands double attention to the driver’s actions, as the time available for avoidance is lessened greatly.

Whether you are in town or out in the country, timing is important in any passing situation. If you get frustrated and start twisting your throttle at the wrong time just to let it out, you’re doing yourself a disservice, and probably getting hung up behind a car you needn’t, just because of the bad timing that your frustration has created. Instead, adopt a professional attitude about coping with traffic. §J

Current subscribers can access the complete Cycle World magazine archive Register Now

More From This Issue

Dan Hunt

-

Competition

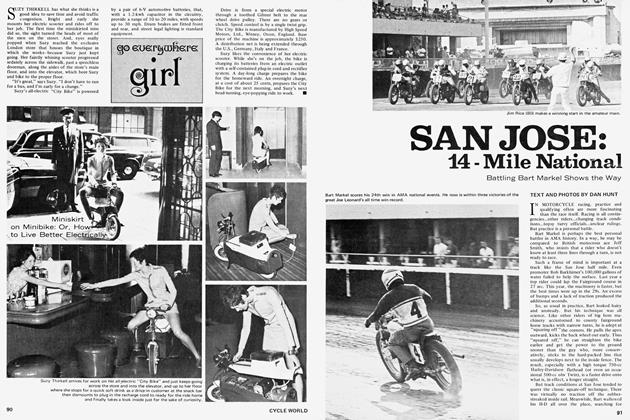

CompetitionSan Jose: 14 - Mile National

NOVEMBER 1968 By Dan Hunt -

Special Features

Special FeaturesFrank Heacox Sells Helmets. Lots of Them. But He Opposes the Helmet Law. He Is, You See, A Motorcyclist. And We Can Thank Our Lucky Stars.

APRIL 1970 By Dan Hunt -

Special Preview Features:

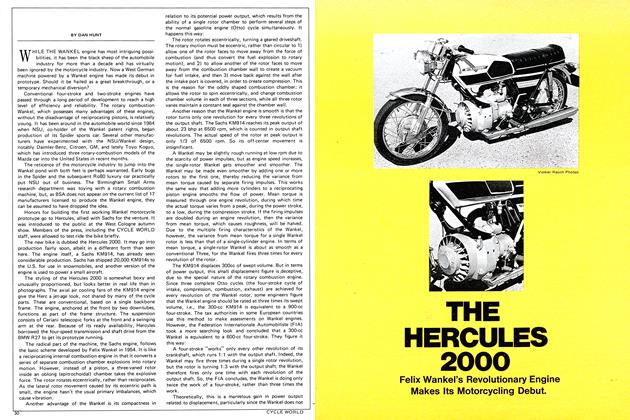

Special Preview Features:The Hercules 2000

JAN 1971 By Dan Hunt