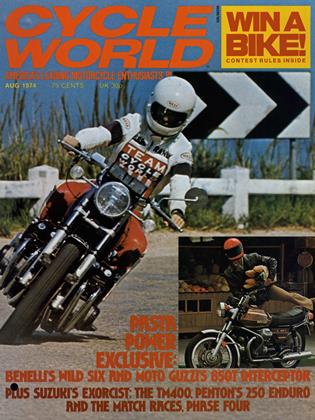

BENELLI 750 SEI

Cycle World Road Test

Six Channel Sound On Two Wheels

COUNT TO SIX. One, two, three, four, five, six. Now count backwards, six, five, four, three, two, one. Think of those numbers as cylinders...cylinders in a motorcycle, all in a row, rumbling down there beneath you. Think real hard about that...a six cylinder motorcycle. Not four, not three, not two or one...six. Can you for a moment imagine what the sound of the engine would be like, the smoothness of the throttle response and the turbine-like power delivery?

If you are blessed with an especially good imagination, perhaps you just conjured up in your mind a pretty good semblance of the new Benelli 750 Six, or Sei, if you will. But then again, you’ve probably already seen photos of the Machine in several ads, or read the preview in the February 1973 CYCLE WORLD, shortly after the machine was unveiled for the first time in Italy.

So you ask, “Where has it been?” Well, you might say that it has been in sort of a “controlled hiding,” appearing at selected shows and exhibitions around the world, tempting the potential customers and generating interest in the remainder of the Benelli line.

This is okay to a degree, but after a year and a half much of the newness is worn off and one is apt to be very suspicious of the chances that there will ever be a production model. And that’s how we were beginning to feel until we had the opportunity to again see one of the prototype models that was being displayed at the Motorcycle Dealer News Show in Houston early this year. Not only did we get to gawk at it, but we took a short ride as well. Funny how our interest in the Six was suddenly renewed.

But a quick, five-minute spin doesn’t constitute a CYCLE WORLD road test, so arrangements were made with Benelli’s U.S. Distributor, Cosmopolitan Motors, to travel to Pesaro, Italy to evaluate one of the latest prototypes at the factory. There we had a chance to run the Six ragged over twisty mountain roads of the Adriatic Seacoast, do some high speed touring on the Autostradas and meander along the cobblestoned alleyways of old Italy. And the results were surprising.

The Six (and the smaller 500 Four), came about in sort of an interesting way, and they owe their existence mostly to one man. Alejandro de Tomaso purchased the Benelli concern back in 1971 and decided that it forthwith needed an irpage builder. What an understatement. Almost immediately, design work was begun on two new multis, a 500 Four and the 750 Six.

To design completely new motorcycles from the ground up is much more than a simple undertaking; to accomplish the feat overnight (and in Italy no less), is near impossible. However, de Tomaso was in a hurry. He didn’t get wealthy by procrastinating, and he wasted no time with this plan. And in the allotted time schedule he had but one choice; copy closely a successful existing multi engine design (Honda), tack on two more cylinders, hang it in proven chassis geometry and do a big styling number. Spring the package on an anxious press and worry later about producing the thing, because in Italy that could never happen overnight.

In the meantime, the prototypes could be making the rounds and garnering lots of attention (which they have done), and the de Tomaso hat trick would be a success. Has it worked? We would say absolutely. But you can’t keep the public hanging on forever. Actions speak louder than words, and now it’s time for action. And from what we saw at the factory in Pesaro, where the Fours were rolling off the assembly lines, we think it’s safe to say that by the time you read this the Sixes will be doing the same.

And now you want to know if it’s been worth the wait...right? To begin with, don’t expect to see Benelli Sixes all over creation. Tentative plans indicate that the factory hopes to supply the United States with approximately 200 of the GT machines. Projected cost of the new model falls between $3000 and $3500. So that leaves many of the hopefuls out right off the bat.

We just thought you should have the bad news first. With that price tag, the new Six falls into the category of the BMW R90S; just how much is too much to pay for a motorcycle? And what does a two-wheeler that expensive have to offer?

The Benelli Sei is not a racer’s motorcycle. It will not meag the criteria necessary to make it a superb tourer either. ArW certainly it’s no commuter bike. But what it is, and the niche it fills, is very special, de Tomaso’s “baby” is a GT “Sports” special, apart from and unlike the others. It is a bike for an owner who wants to be recognized as standing apart from the crowd.

It is a machine for the rider who demands exotic mechanical and running quality. The same type of person who will long for the day he owns a Ferrari Daytona will have a love affair with the Benelli Six. He must own one, if for nothing else but to hear the sound of such a creation.

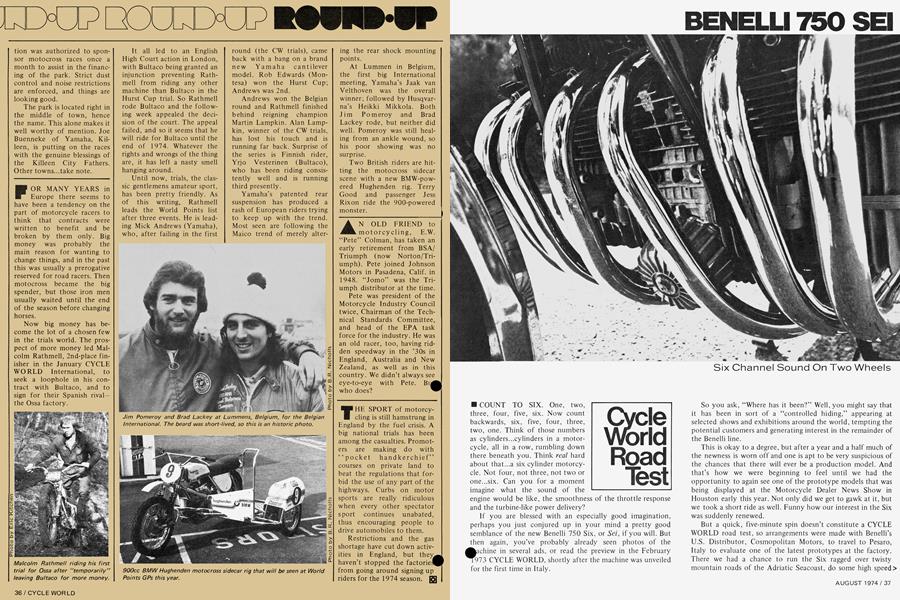

It’s not at all hard to spot the Six at a glance. Angular, bold styling created by Ghia, coupled with the wide power plant and three gleaming chrome exhaust pipes per side demand closer inspection. Fenders are chromed steel, again with angular sculpturing to blend with the remainder of the machine.

Polished fork legs on the prototype model we tested are actually lengthened Moto Guzzi units borrowed from the 750 Sport. Production Sixes will carry Marzocchi suspension frong and rear. Forks will be even longer than those on the te^ machine to gain some extra ground clearance in cornering.

The polished alloy front hub is laced to a Borrani aluminum rim and also handles huge twin discs for braking. We saw one prototype Six with the front brake calipers mounted on the rear of the fork legs, but like the production models, our test machine had them attached at the front. To keep the front end styling clean, no fork gaiters are used. The bright metal look is carried out on the headlight nacelle and polished aluminum triple clamps, as well as on the upper fork covers d headlight ears.

From a styling standpoint, the instrument cluster is highly unusual. The round dial faces are fitted into flat black boxes that sandwich a warning light cluster between them. While the appearance might be unusual, their efficiency is not. The plastic faces reflect glare back into the rider’s eyes and the warning lights, including the turn indicator flashers, are difficult to notice in normal daylight. Though the unit pictured is calibrated in kilometers per hour, those on bikes destined for the U.S. will be in miles per hour.

With all of the apparent effort expended into the design of the instruments, it’s too bad that someone couldn’t have thought about locating the ignition switch near them as well. Like Honda, Benelli has stuck the switch down under the left side of the fuel tank, making it a chore to find and use. Another bad feature about this particular switch is the fact that the wiring on the back portion of the unit is exposed, making it an easy mark for thieves who are intent upon hotwiring the machine. On the Honda, the rear portion of the switch is encased in a metal housing, which slows the crooks É)wn a tad.

W Handlebar switches are of the new type from Italy. Though an improvement over what we’ve seen in the past, they’re still far from perfect. The turn signal switch is activated by the rider’s left thumb, but the detent mechanism isn’t strong enough. What usually happens is that the rider tries to switch off the indicator and slides right across the “off’ detent and turns the opposite light on. It takes some of your attention away from the road to do it correctly.

Another bad design is the tab that operates the headlight beams. It’s just too far away from the rider’s thumb for him to operate without taking his hand from the grip. On a twisty road at night that is a definite bummer.

Riders who are interested in the touring aspects of the Six will thrill to the smoothness of the in-line engine, but will not be happy with the fuel tank’s limited four-gallon capacity and the thin, hard seat. Aside from frequent drive chain servicing, these are the only drawbacks to long distance travel on the 750.

The steel tank is easily removed to facilitate servicing, and the seat flips up in a conventional manner to reveal a tool tray with toolkit and to allow access to the 12-volt battery. Side covers are also steel and are finished to match the tank.

Unbolting the panels reveals more electrics and a fuse box, as well as the air box and paper filter element. We wonder if the production units will come standard with air filters, since some of the prototypes we saw didn’t have them; a few others did. The reason we wonder is that the 650 four-stroke Twin brought into this country by Benelli does not have air cleaners, a feature the bike is infamous for. Let’s just hope the Six gets them.

Benelli’s Six shares the same double downtube frame with the smaller 500 Four; in fact, many of the components are interchangeable. That is one reason the two machines appear so similar...they are. And, much the same as many European machines, the Benelli has the right combination in frame geometry. It steers like a dream.

The limiting factor in fast cornering is not a wiggle or a wobble as it is with some bikes. What stops you from going around corners like a cannonball dropped down a chimney is ground clearance. The engine is simply too wide to allow much in the way of lean.

First the center stand starts grinding away at the pavement (there is no side stand to worry about), and when that is worn down far enough, the outermost pipes on each side make contact with the ground. Don’t get the idea that this ground contact is only accomplished at incredible lean angles; it happens surprisingly early.

This is why production models will have longer fork assemblies. But then we can wonder what a higher center of gravity will do to the good-handling traits that the machine has now. Because for the size and weight of the machine, it is wonderfully nimble at low speeds. There is none of that tendency to “fall into the turn” that plagues a couple of the popular big bores presently available.

It’d be wise, as the owner of a Benelli Six, to check up on the condition of your battery often. This is necessary because there is no kick starter to help prod the engine into life should the electric starter be on the tired side. But our test bike fired effortlessly each and every time, although the choke was required briefly after the engine had been allowed to fully cool off.

We have made a few references to the sounds this engine produces. There is simply no other motorcycle on the road that emits decibels the way this Benelli does. It is quiet, yet very exciting to listen to. In the automotive world, a V-12 Ferrari sounds quite similar. Were a dealer trying to make a sale to an undecided customer, merely starting the engine would have the guy running for his Parker T-Ball Jotter. It’s that convincing.

What about performance? Well, that’s pretty convincing too.

For years motorcycle journalists have been complaining about excessive vibration in many different motorcycles; th<^ came a few that set new standards. And, as you might guess, im this area Benelli’s Six sets a new mark for others to shoot at. The firing impulses and rotating masses of this engine are so smooth that it really is like turning up the rheostat on an electric motor when you twist the throttle. Six cylinders is why.

But this engine unit isn’t some new and earth-shaking design. It is virtually a dead ringer for the Honda Four, with two additional cylinders. Even the bore/stroke dimensions are identical to those on the Japanese 500. The crankshaft is a helty one-piece unit that rides in seven plain automotive-type bearings. The crank center carries a sprocket that drives a single-row chain, which in turn connects to and spins the camshaft. The one-piece cam is so long that it looks for ali the world like it was extracted from an auto engine. Another chain, this time a Morse Hy-Vo unit, is the primary drive.

Crankcases on each of the prototype models are sandcast, but production castings are due to start rolling out of the Moto Guzzi plant (also de Tomaso owned), soon. Cylinder assemblies on pre-production models are sandcast as wellJ Appearance wise, production engine units will look nearl^ identical to the unit seen in the photos here.

BENELLI

750 SEI

Although Honda’s four-cylinder models utilize one carburetor per cylinder, the 750 Benelli thankfully goes a simpler route. With six pistons and all the other associated paraphernalia, a total of six carburetors was the last thing needed. So by making use of aluminum Y-shaped manifolds, one carb—in this case a 29mm Dell’Orto—supplies two cylinders with premium fuel. Three carbs is all that is needed!

As we mentioned earlier, starting is quick and simple, and once the engine comes alive you know it. Revs build and die quickly when you blip the throttle, due to very little flywheel inertia. Drop the five-speed gearbox into low with a downward touch from your left boot; there’s a little ka-clunk as gears mesh. Ease out the clutch lever and rev the engine a bit higher than you would normally. The clutch will have to be slipped some too.

Though the bike feels plenty hefty at standstill, that feeling virtually disappears as you motor smoothly away. Initially, gear changes will be on the sloppy side if you’re not use to a machine with light flywheels. But not helping the situation is an inordinate amount of drive line snatch (a la Honda 360), which makes you jerk along at low speeds until you can develop a very fine touch with your throttle hand.

Where this tendency proved most awkward was in a friendly dice with another motorcycle on a twisty section of road. The slightest change in throttle opening will put the machine into a jerky motion that is anything but confidenceinspiring when heeled well over. Add to this the ground clearance problem mentioned earlier, and you can really have your hands full trying to stay in sight of some dude on a 350 Yamaha. Better you should back off and leave the road racing to someone else.

The Six is most pleasant to ride between about 35 and 90 mph. At these speeds it happily hums along, at ease enough with the highway as a hang glider is in a thermal. Gear changes are positive from a transmission standpoint, but the ratios could be a little closer together for maximum acceleration. Top gear, in fact, acts slightly like an overdrive, where it takes some time and distance to pull top speed.

Braking power is phenomenal with the huge twin discs up front and large drum at the rear. A rider can stop the heavy machine in an extraordinarily short amount of space with lots of control. The front units feed back plenty of feel to t rider’s fingers. You can lock the front tire at will, but only vT you want to.

In hard going the rear unit shows signs of fade, and in two repeated stops from 100 mph, it went away completely. Recovery, however, comes quickly. As long as you’re not continually pushing the thing to its limits, it works fine. And even when it gives up, you can always rest assured that the front units will do the job for you.

At the drag strip, we can’t remember a machine that could light up the rear tire for such a distance. Shades of T.C. Christensen’s Fueler! Though we recorded some low-13-second elapsed times, it would take a better rear tire to get into and turn 12s consistently. So don’t think too seriously about blowing off all the local Z-l guys with this one. Super strong performance...si. Drag strip terror...no.

What you have in the end is a motorcycle that is not the fastest thing from stoplight to stoplight, not the quickest over Mulholland Highway, not an economy winner or a touring trickster. What it does do though, it does with the best, and it does it with a novelty appeal and sound unsurpassed by ai^^ other machine to date. Does that make it worth more than three grand? Well...that’s kinda up to you...now isn’t it?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

August 1974 -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1974 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

August 1974 -

Departments

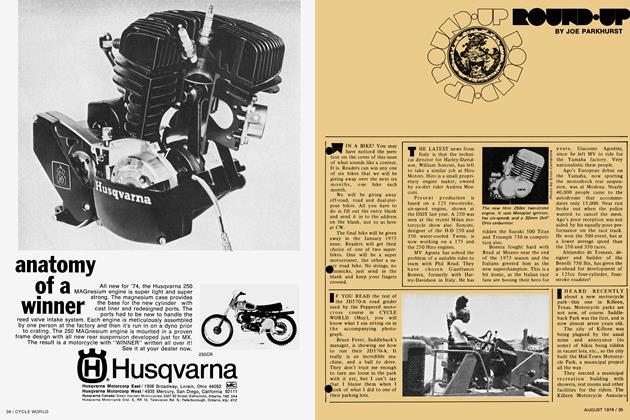

DepartmentsRound·up

August 1974 By Joe Parkhurst -

Features

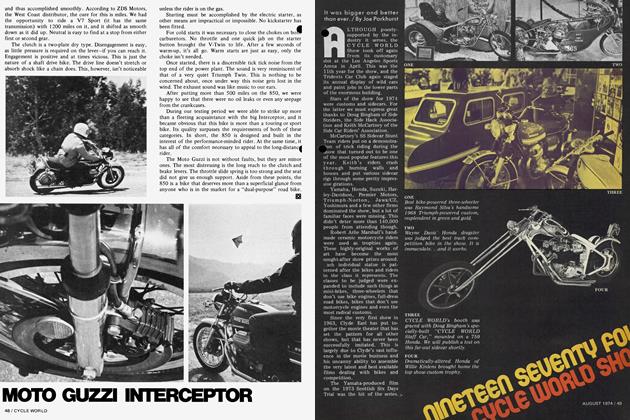

FeaturesNineteen Seventy Four Cycle World Show

August 1974 By Joe Parkhurst -

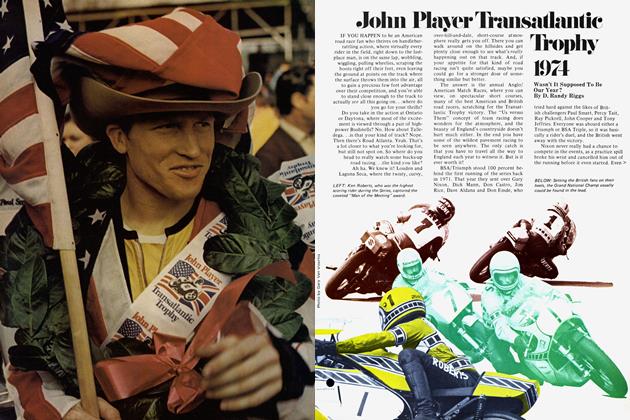

Competition

CompetitionJohn Player Transatlantic Trophy 1974

August 1974 By D. Randy Riggs