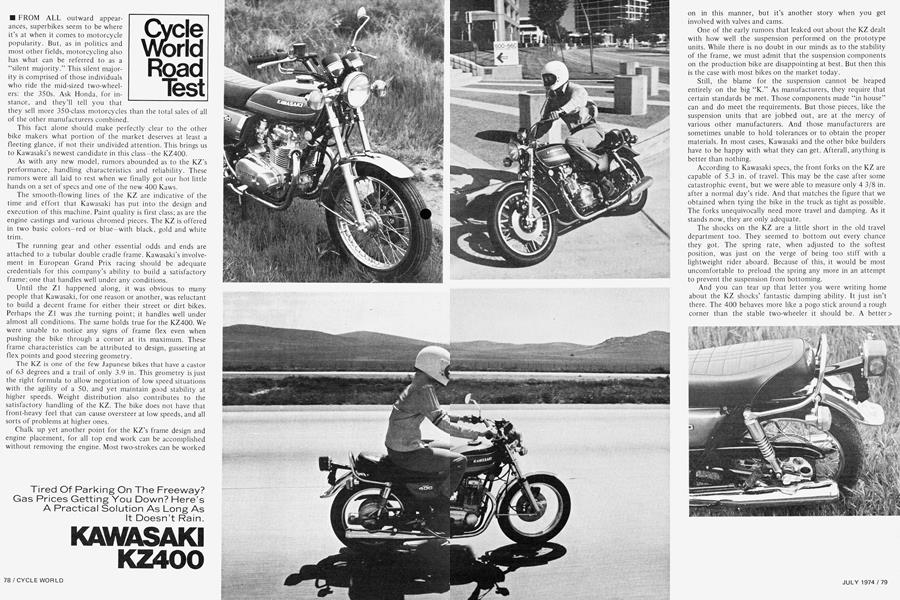

KAWASAKI KZ400

Cycle World Road Test

Tired Of Parking On The Freeway? Gas Prices Getting You Down? Here’s A Practical Solution As Long As It Doesn’t Rain.

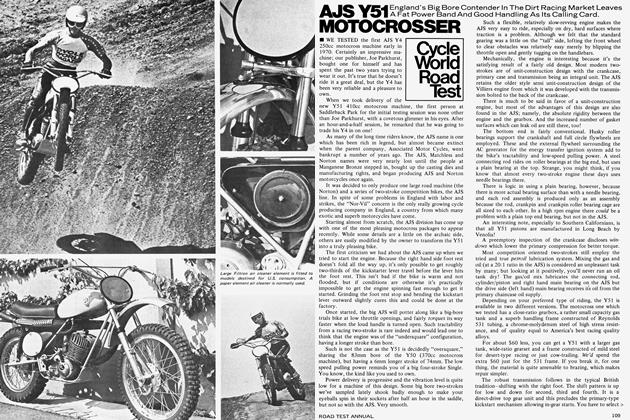

FROM ALL outward appearances, superbikes seem to be where it’s at when it comes to motorcycle popularity. But, as in politics and most other fields, motorcycling also has what can be referred to as a “silent majority.” This silent majority is comprised of those individuals who ride the mid-sized two-wheelers: the 350s. Ask Honda, for instance, and they’ll tell you that they sell more 350-class motorcycles than the total sales of all of the other manufacturers combined.

This fact alone should make perfectly clear to the other bike makers what portion of the market deserves at least a fleeting glance, if not their undivided attention. This brings us to Kawasaki’s newest candidate in this class—the KZ400.

As with any new model, rumors abounded as to the KZ’s performance, handling characteristics and reliability. These rumors were all laid to rest when we finally got our hot little hands on a set of specs and one of the new 400 Kaws.

The smooth-flowing lines of the KZ are indicative of the time and effort that Kawasaki has put into the design and execution of this machine. Paint quality is first class; as are the engine castings and various chromed pieces. The KZ is offered in two basic colors-red or blue-with black, gold and white trim.

The running gear and other essential odds and ends are attached to a tubular double cradle frame. Kawasaki’s involvement in European Grand Prix racing should be adequate credentials for this company’s ability to build a satisfactory frame; one that handles well under any conditions.

Until the Z1 happened along, it was obvious to many people that Kawasaki, for one reason or another, was reluctant to build a decent frame for either their street or dirt bikes. Perhaps the Z1 was .the turning point; it handles well under almost all conditions. The same holds true for the KZ400. We were unable to notice any signs of frame flex even when pushing the bike through a corner at its maximum. These frame characteristics can be attributed to design, gusseting at flex points and good steering geometry.

The KZ is one of the few Japanese bikes that have a castor of 63 degrees and a trail of only 3.9 in. This geometry is just the right formula to allow negotiation of low speed situations with the agility of a 50, and yet maintain good stability at higher speeds. Weight distribution also contributes to the satisfactory handling of the KZ. The bike does not have that front-heavy feel that can cause oversteer at low speeds, and all sorts of problems at higher ones.

Chalk up yet another point for the KZ’s frame design and engine placement, for all top end work can be accomplished without removing the engine. Most two-strokes can be worked on in this manner, but it’s another story when you get involved with valves and cams.

One of the early rumors that leaked out about the KZ dealt with how well the suspension performed on the prototype units. While there is no doubt in our minds as to the stability of the frame, we must admit that the suspension components on the production bike are disappointing at best. But then this is the case with most bikes on the market today.

Still, the blame for the suspension cannot be heaped entirely on the big “K.” As manufacturers, they require that certain standards be met. Those components made “in house” can and dö meet the requirements. But those pieces, like the suspension units that are jobbed out, are at the mercy of various other manufacturers. And those manufacturers are sometimes unable to hold tolerances or to obtain the proper materials. In most cases, Kawasaki and the other bike builders have to be happy with what they can get. Afterall, anything is better than nothing.

According to Kawasaki specs, the front forks on the KZ are capable of 5.3 in. of travel. This may be the case after some catastrophic event, but we were able to measure only 4 3/8 in. after a normal day’s ride. And that matches the figure that we obtained when tying the bike in the truck as tight as possible. The forks unequivocally need more travel and damping. As it stands now, they are only adequate.

The shocks on the KZ are a little short in the old travel department too. They seemed to bottom out every chance they got. The spring rate, when adjusted to the softest position, was just on the verge of being too stiff with a lightweight rider aboard. Because of this, it would be most uncomfortable to preload the spring any more in an attempt to prevent the suspension from bottoming.

And you can tear up that letter you were writing home about the KZ shocks’ fantastic damping ability. It just isn’t there. The 400 behaves more like a pogo stick around a rough corner than the stable two-wheeler it should be. A better> spring and more travel and damping are definitely in order here.

Both front and rear wheels are 18 in. in diameter. A 3.25-in. rib tire is mounted to the front, and a 3.50-in. universal to the rear. Here again, we are faced with the compromise of anything being better than nothing. For one reason or another, Kawasaki is unable to obtain Dunlop tires. Instead, Yokohama supplies the treads for the KZ. Never in the many years that we have been involved with bikes has Yokohama been known for producing tires with good adhesion qualities. The tires on the KZ hold true to form.

When riding on dry pavement traction is satisfactory, provided you aren’t trying to push the bike to its limit. If you are, be prepared for both ends to get a little skittish. On wet days the KZ might as well be left at home in a nice dry garage, wet pavement traction leaves quite a bit to be desired.

The braking figures in our specifications do not really reflect the efficiency, or in this case.the inefficiency of the stoppers. Rather, they are representative of the lack of tire adhesion. It is almost impossible to touch the rear brake without squealing the tire or locking the wheel. The front brake is a floating hydraulic disc. Both it and the rear binder perform well even in the wet. It’s too bad this good braking can’t be transferred to the ground.

As with the Yamaha, the KZ utilizes contra-rotating weights that help dampen the engine vibration that is so common to the vertical Twin. The Yamaha Twin is rock steady at all speeds, but we found the KZ to be somewhat of a vibrator even with these balance weights.

Perhaps one of the biggest differences between the TX and the KZ is the crankshaft arrangement. The 500 has a 180-degree crank, which means that when one piston is at TDC (top dead center), the other is at BDC (bottom dead center). This set-up is smoother to begin with than the 360-degree crank arrangement in the 400, which puts both pistons at TDC simultaneously.

Up to this point, everything is fine. At least on paper. The crank is balanced at 50 percent of the reciprocating weight. The two contra-rotating weights are each balanced at 25 percent of the reciprocating weight. Theoretically, these two should cancel one another out and make for a glass-smooth ride. However, this is not the case. What we may have is a secondary vibration that, in order to be alleviated, requires that the crank or weights be rebalanced.

Incidentally, this 360-degree arrangement was chosen after an extensive consumer survey conducted by Kawasaki. The biggest reason for the 360-degree crank, believe it or not-, was sound! Second was the fact that this arrangement is easier on the life of drive line components. This is due to the alternating power strokes.

The KZ has almost as much chain running around inside the engine as the TX500 Yamaha does (approximately four feet). The longest chain operates the cam, which in turn opens and closes the single intake and exhaust valve in each of the two cylinders. “Why didn’t Kawasaki design an eight-valve head similar to that on the TX500?” you ask. Well, while this would undoubtedly have improved efficiency and performance, it would also have put the 400 out of the market it was aimed for.

Unlike most Japanese bikes, the KZ does not have a gear-driven primary. Because of this, it also does not have primary kick starting. A chain drive was necessary because of the placement of the balance weights, which are located in front of and behind and on the same center line as the crankshaft.

If a conventional roller chain was used as a primary drive, some type of adjuster would be necessary to take up slack in the chain that is caused by wear. To eliminate this, and to reduce maintenance chores, a Hy-Vo chain was chosen. This chain can best be described as an inverted-tooth link belt. It is extremely strong, quiet in operation, and accounts for a minimum of power loss. Due to the characteristics of the Hy-Vo, no adjuster is necessary; it is self-compensating.

Like the Zl, the 400 also has a PCV system. All transmission and crankcase pressure is vented up through the cam chain tunnel, through oil trappings in the head, and into an external passage that routes these vapors back into the intake tract.

A most noticeable departure for Kawasaki is the adoption of two 36mm Keihin constant velocity carburetors. Until now Kawasaki has used Mikuni “slide-type” mixers. The few disadvantages of the CV carburetor are far outweighed by the advantages of its design. Disadvantage number one is that most people will not be able to grasp the operation principle of this carb. The second is that, at the present time, these carburetors have a slight surge that is evident when running over rough ground. This is caused by a wandering slide.

But, because of the carburetor’s design, it is self-compensating for any changes in altitude. The biggest and most promising advantage, particularly today, is fuel economy. Because of the improved control over venturi size, the gas can be better regulated to exactly meet the engine requirements.

Without going into a complete technical analysis, it might be explained that the CV carb is comprised of a butterfly, which is cable-operated, and a slide that works entirely on the difference in air pressure between the venturi and the atmosphere. Briefly, this slide is attached to a piston, the top of which is vented to the venturi. The bottom of the piston is vented to the atmosphere.

The quicker the air flows through the venturi (controlled by the butterfly opening), the lower the pressure. This low pressure on top of the piston causes the slide to rise. Once the weight and pressure acting on the piston stabilize with the atmosphere, the slide stops moving. On deceleration, the pressure above the piston (and in the venturi) increases, and the slide drops. This CV carb has an effective venturi size of from 14mm to 36mm.

Although primary kick starting is not included, the KZ still has electric starting, a feature considered indispensable by most people. As with the majority of electric-start bikes, the drill is quite simple—key on, gas on, choke and push the button. Like magic, the engine roars to life instantly. Once started, it is necessary to turn the choke off, or at least partially, to prevent an over-rich condition.

For cold starts, it is necessary to give the throttle a helping hand to keep the engine running. About 30 seconds is all the time required for warm-up.

After repeated runs at the drag strip, we were surprised at the stamina of the KZ’s clutch. It had no overheating tendencies. This was also true under heavy traffic conditions. As might be expected, the operation was both smooth and positive.

The gear box worked in much the same way. There were times when the KZ hung up in third gear, but we feel that that was our fault for not applying enough pressure to the lever. The gear ratios were well-spaced, allowing a good selection for around-town or highway cruising.

During our testing, the KZ averaged 47 mpg, which is a more than respectable figure for any road bike. With a gas tank capacity of 3.7 gal., the KZ offers an approximate range of 170 miles.

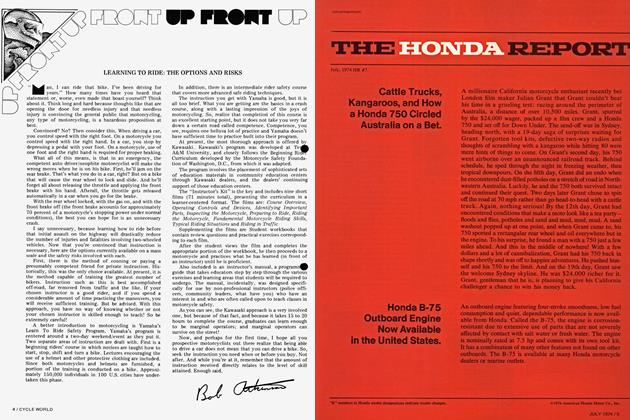

As a commuter bike the KZ will make almost any rider feel right at home behind the bars. To us the 400 had a rather “standardized” feel; one of being on top of everything. The Zl, on the other hand, has a seating position that makes us feel a part of the bike.

As for the rest of the bike, it is finished as expected. Folding footpegs, miserable hand grips, easily-read instruments, the usual idiot lights and a warning light to indicate whether the stop light is working.

Despite the poor choice of tires and what we consider more than necessary vibration, Kawasaki has done a commendable job in the execution of the KZ400. It doesn’t leak a drop .of oil, and the exhaust note is pleasant to the ear.

Luckily, the KZ is intended to be a commuter bike. Chances are that most people won’t ride it long enough or hard enough for the tires and vibration to get to them. Priced at $1170, the KZ will show well against the other commuter specials. IS

KAWASAKI

KZ400

$1170

SPECI FICATION

PERFORMANCE

TES CONDITIONS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue