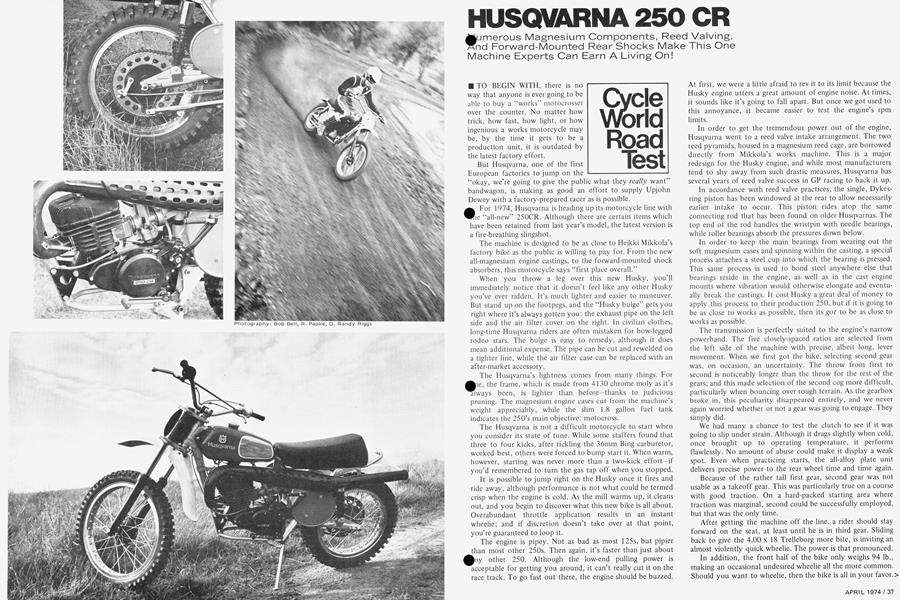

HUSQVARNA 250 CR

Cycle World Road Test

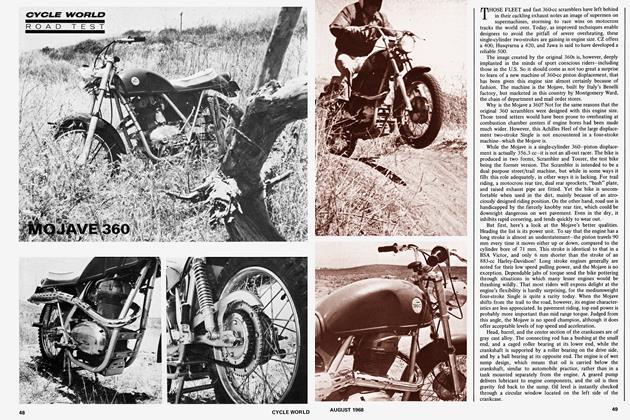

Numerous Magnesium Components, Reed Valving, And Forward-Mounted Rear Shocks Make This One Machine Experts Can Earn A Living On!

TO BEGIN WITH, there is no way that anyone is ever going to be able to buy a “works” motocrosser over the counter. No matter how trick, how fast, how light, or how ingenious a works motorcycle may be, by the time it gets to be a production unit, it is outdated by the latest factory effort.

But Husqvarna, one of the first European factories to jump on the “okay, we’re going to give the public what they really want’ bandwagon, is making as good an effort to supply Upjohn Dewey with a factory-prepared racer as is possible.

For 1974, Husqvarna is heading up its motorcycle line with ^Rie “all-new” 25OCR. Although there are certain items which have been retained from last year’s model, the latest version is a fire-breathing slingshot.

The machine is designed to be as close to Heikki Mikkola’s factory bike as the public is willing to pay for. From the new all-magnesium engine castings, to the forward-mounted shock absorbers, this motorcycle says “first place overall.”

When you throw a leg over this new Husky, you’ll immediately notice that it doesn’t feel like any other Husky you’ve ever ridden. It’s much lighter and easier to maneuver. But stand up on the footpegs, and the “Husky bulge” gets you right where it’s always gotten you: the exhaust pipe on the left side and the air filter cover on the right. In civilian clothes, long-time Husqvarna riders are often mistaken for bow-legged rodeo stars. The bulge is easy to remedy, although it does mean additional expense. The pipe can be cut and rewelded on a tighter line, while the air filter case can be replaced with an after-market accessory.

The Husqvarna’s lightness comes from many things. For ^^ie, the frame, which is made from 4130 chrome moly as it’s æways been, is lighter than before-thanks to judicious pruning. The magnesium engine cases cut trom the machine’s weight appreciably, while the slim 1.8 gallon fuel tank indicates the 250’s main objective: motocross.

The Husqvarna is not a difficult motorcycle to start when you consider its state of tune. While some staffers found that three to four kicks, after tickling the 36mm Bing carburetor, worked best, others were forced to bump start it. When warm, however, starting was never more than a two-kick effort—if you’d remembered to turn the gas tap off when you stopped.

It is possible to jump right on the Husky once it fires and ride away, although performance is not what could be termed crisp when the engine is cold. As the mill warms up, it cleans out, and you begin to discover what this new bike is all about. Overabundant throttle application results in an instant wheelie; and if discretion doesn’t take over at that point, you’re guaranteed to loop it.

The engine is pipey. Not as bad as most 125s, but pipier than most other 250s. Then again, it’s faster than just about ^ny other 250. Although the low-end pulling power is acceptable for getting you around, it can’t really cut it on the race track. To go fast out there, the engine should be buzzed. At first, we were a little afraid to rev it to its limit because the Husky engine utters a great amount of engine noise. At times, it sounds like it’s going to fall apart. But once we got used to this annoyance, it became easier to test the engine’s rpm limits.

In order to get the tremendous power out of the engine, Husqvarna went to a reed valve intake arrangement. The two reed pyramids, housed in a magnesium reed cage, are borrowed directly from Mikkola’s works machine. This is a major redesign for the Husky engine, and while most manufacturers tend to shy away from such drastic measures, Husqvarna has several years of reed valve success in GP racing to back it up.

In accordance with reed valve practices, the single, Dykesring piston has been windowed at the rear to allow necessarily earlier intake to occur. This piston rides atop the same connecting rod that has been found on older Husqvarnas. The top end of the rod handles the wristpin with needle bearings, while roller bearings absorb the pressures down below.

In order to keep the main bearings from wearing out the soft magnesium cases and spinning within the casting, a special process attaches a steel cup into which the bearing is pressed. This same process is used to bond steel anywhere else that bearings reside in the engine, as well as in the cast engine mounts where vibration would otherwise elongate and eventually break the castings. It cost Husky a great deal of money to apply this process to their production 250, but if it is going to be as close to works as possible, then its got to be as close to works as possible.

The transmission is perfectly suited to the engine’s narrow powerband. The five closely-spaced ratios are selected from the left side of the machine with precise, albeit long, lever movement. When we first got the bike, selecting second gear was, on occasion, an uncertainty. The throw from first to second is noticeably longer than the throw for the rest of the gears; and this made selection of the second cog more difficult, particularly when bouncing over rough terrain. As the gearbox broke in, this peculiarity disappeared entirely, and we never again worried whether or not a gear was going to engage. They simply did.

We had many a chance to test the clutch to see if it was going to slip under strain. Although it drags slightly when cold, once brought up to operating temperature, it performs flawlessly. No amount of abuse could make it display a weak spot. Even when practicing starts, the all-alloy plate unit delivers precise power to the rear wheel time and time again.

Because of the rather tall first gear, second gear was not usable as a takeoff gear. This was particularly true on a course with good traction. On a hard-packed starting area where traction was marginal, second could be successfully employed, but that was the only time.

After getting the machine off the line, a rider should stay forward on the seat, at least until he is in third gear. Sliding back to give the 4.00 x 18 Trelleborg more bite, is inviting an almost violently quick wheelie. The power is that pronounced.

In addition, the front half of the bike only weighs 94 lb., making an occasional undesired wheelie all the more common. Should you want to wheelie, then the bike is all in your favor. In fact, when you want to show off a little, the Husky is right in there with you. It is one of the easiest machines on which to maintain a through-the-gears unicycle attitude. Part of this ability comes from its light weight and balance, while the rest comes from the engine’s pull (once on the pipe), and the quick-shifting, perfectly-spaced gearbox.

One of the other major changes for ’74, is in the area of the rear shock absorbers. If you’ve been paying close attention to the International motocross scene, you’ll remember that during this last GP season, nearly all of the top riders’ bikes (except Yamaha), had the rear section of their frames modified, and their shocks mounted several inches forward of their normal position. Husqvarna is the first manufacturer to employ this technique on a production motocrosser.

The purpose of this modification is to increase rear wheel travel, without increasing shock travel. There is one drawback, though. With the shocks in this position, the portion of the swinging arm behind the shock absorbers acts as a lever, increasing the pressure of each impact. This forces the shock to work much harder, and also requires that it be fitted with an extraordinarily strong spring. The Husky comes with Girling shocks, equipped with 110 lb. coils. Although stiff for our lighter staffers, those over 180 lb. will find them perfectly suited. But the question arises about the longevity of the shock absorbers now that they are being overworked.

While Girling shocks have superb damping action, they have never been known for an exceptionally long life span. We understand that the shocks on this Husky are specially designed by Girling for this particular application. They gave us no trouble at all during our test period, but the true test will come at the hands of the every-Sunday-for-three-months racer.

The action of the rear end is excellent. On a relatively smooth track it is difficult to note any difference over earlier Huskies, but get this one out on a torturous track, and the beauty of the system shines through. It has generally been felt for a long time that the front end of a motorcycle could absorb jarring jolts much better than the rear end, but on the Husky this does not hold true. While the forks offer nearly seven inches of cushion, the rear wheel will follow true blue over anything that the front end can absorb. And the front end can absorb quite a lot.

All of us agreed that the handlebars were too wide for our comfort. That isn’t really a problem, because it can be solved with a hacksaw and a little elbow grease. Better that the bars be too wide than too narrow. The seat, a well-padded unit, feels much higher than the 3 HA in. it sits above the ground. Once the machine is moving though, it fits right in. The footpegs are the same old slippery items that Husky has been producing for years. Although these have a few dimply holes in them, they still become difficult to stand on when the going gets wet or muddy. Particularly muddy.

There is one final point that either makes or breaks the Husky as the bike for you. The front end washes out. For the first couple of hours that we rode the bike, we had a difficult time getting it to hold a line. We sat on the rear end of the seat, we sat in the middle, and we sat on the gas cap. Nothing.

It washed out in varying degrees each time. Finally we got it figured out. If you corner with the power on, the front end sticks. Not like glue, but it stays put nonetheless. This, however, brings out another problem.

When cornering with the power on, it doesn’t matter > whether or not the bike is on the pipe. But if it is, you have to be minutely exacting with your right hand, or suffer a spin out. If the bike is not on the pipe as you corner, then it will be coming on the pipe as you exit the bend.

For us, it was imperative that the machine be in as close to a vertical position as possible when the horsepower hit, or one of two things would result. If we were sitting on the forward portion of the seat, the bike threw a full-lock slide—something that the Husky doesn’t do well when you want it to. But, if we were sitting in the middle or rear half of the seat, the tire took hold and the bike squirted off in whatever direction its momentum was pushing it—generally off of the best line.

With practice, this problem could be mastered. We noticed ourselves getting into trouble with the power less and less as we became accustomed to it. But it is going to take an expert motocrosser to be able to get the Husky around corners with maximum efficiency. We realize that Heikki Mikkola doesn’t have this problem, since he never shuts his throttle off. But Husky can’t sell you a bike with his abilities built in.

The brakes are beautiful. Both the front and rear binders offer progressive braking force, and feed the information back to the rider’s hand and foot. These are the kind of brakes every motocrosser should have. The only fault that could be found was the brake pedal that sits higher than we would like. Operating the rear brake meant lifting your foot off the peg to step on the pedal. By adjusting the brake loosely, we could, once the brake had been applied, stand on the peg while braking. But this still meant lifting the leg up to get to the pedal.

The Husqvarna 250CR comes out as a bike that a novice can win on—particularly on a rough track where the machine’s superior suspension can play games with the competition. But it is much more than just that. In the hands of an expert, it is a machine that can earn him a living.

HUSQVARNA

$1475.00

View Full Issue

View Full Issue