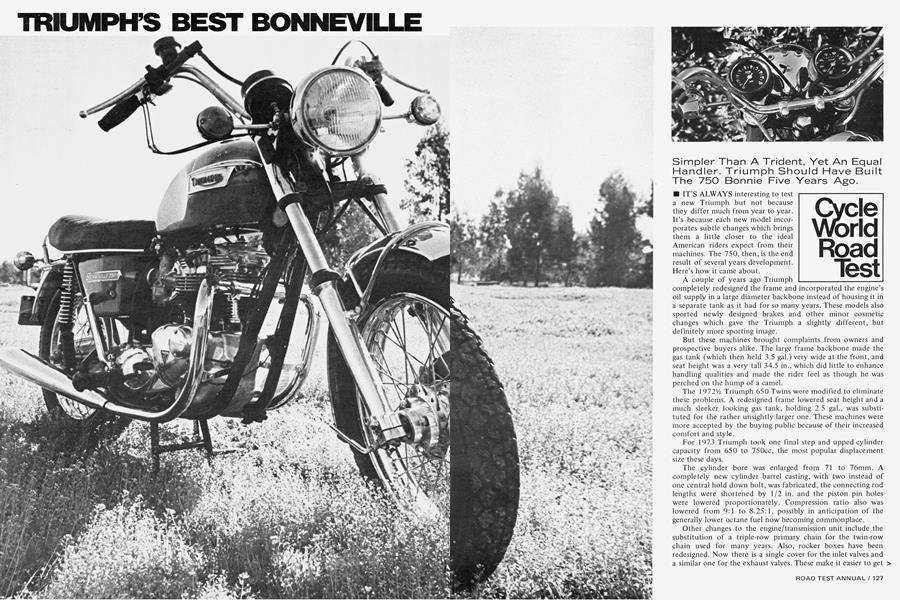

TRIUMPH'S BEST BONNEVILLE

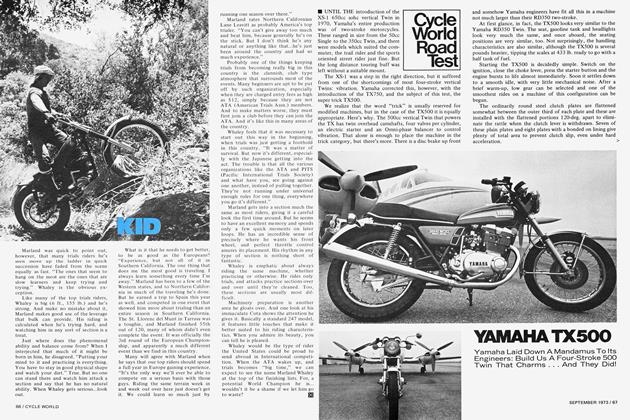

Cycle World Road Test

Simpler Than A Trident, Yet An Equal Handler. Triumph Should Have Built The 750 Bonnie Five Years Ago.

IT’S ALWAYS interesting to test a new Triumph but not because they differ much from year to year. It’s because each new model incorporates subtle changes which brings them a little closer to the ideal American riders expect from their machines. The 750, then, is the end result of several years development. Here’s how it came about.

A couple of years ago Triumph

completely redesigned the frame and incorporated the engine’s oil supply in a large diameter backbone instead of housing it in a separate tank as it had for so many years. These models also sported newly designed brakes and other minor cosmetic changes which gave the Triumph a slightly different, but definitely more sporting image.

But these machines brought complaints from owners and prospective buyers alike. The large frame backbone made the gas tank (which then held 3.5 gal.) very wide at the front, and seat height was a very tall 34.5 in., which did little to enhance handling qualities and made the rider feel as though he was perched on the hump of a camel.

The 197214 Triumph 650 Twins were modified to eliminate these problems. A redesigned frame lowered seat height and a much sleeker looking gas tank, holding 2.5 gal., was substituted for the rather unsightly larger one. These machines were more accepted by the buying public because of their increased comfort and style.

For 1973 Triumph took one final step and upped cylinder capacity from 650 to 750cc, the most popular displacement size these days.

The cylinder bore was enlarged from 71 to 76mm. A completely new cylinder barrel casting, with two instead of one central hold down bolt, was fabricated, the connecting rod lengths were shortened by 1/2 in. and the piston pin holes were lowered proportionately. Compression ratio also was lowered from 9:1 to 8.25:1, possibly in anticipation of the generally lower octane fuel now becoming commonplace.

Other changes to the engine/transmission unit include the substitution of a triple-row primary chain for the twin-row chain used for many years. Also, rocker boxes have been redesigned. Now there is a single cover for the inlet valves and a similar one for the exhaust valves. These make it easier to get exact valve clearance settings and are less prone to oil leakage than the earlier types.

The larger Bonnie is very easy to start. Even on the coldest mornings we found it necessary only to liberally flood the float bowls with the tickler buttons, leave the choke open, and kick once. After a minute’s warm-up the engine settled down to its characteristic 1200 rpm idle. Throttle response from the dual Amal carburetors was very good, in spite of the fact that one carburetor had a slight tendency to flood when the machine was leaned over on the side stand.

One would expect that larger pistons would mean heavier vibration. This isn’t the case with the T140V, however—the factory spent considerable time calculating a suitable balance factor and, except for a slight quiver through the tank at about 3500 rpm, the big Twin vibrates only mildly throughout the rest of the operating range. Rubber-mounted handlebars help ease the vibration to the rider’s hands. The gas tank vibrates, but the foot pegs transmit few of the big Twin’s vibrations to the rider’s feet.

The exception to this was the rear passenger’s foot pegs, which shake quite noticeably when accelerating away from a stop in low gear. At higher speeds we got no complaints from our rear seat passengers and they all commented on the comfortableness of the seat.

The seat, incidentally, is thick enough for good support and has a slight hump in it to prevent the rider from being blown backward while cruising down the highway.

Another commendable feature is a redesigned five-speed transmission that’s now standard equipment. In this gearbox, the layshaft is supported on both ends by needle bearings as before, but the mainshaft rides in a ball bearing on the right-hand end and a heavy-duty roller bearing carries the drive side end where most of the strain to the transmission is located. Gear shifts are short and crisp and it was difficult to miss a gear change. Finding neutral proved to be somewhat of a nuisance after stopping because of an ever-so-slight clutch drag and the closeness of the gear lever positions. It worked best if neutral was selected just before stopping.

Triumph’s six-plate clutch is one of the best we’ve sampled.

It was able to take repeated standing start, full throttle runs at the drag strip without protest or slippage and the take-up action was very smooth indeed. The lack of drag resulted in some very quick shifts and undoubtedly helped achieve a standing quarter-mile time of 13.64 sec.

A 13.64-sec. quarter-mile is not that spectacular for a 750, but there are reasons for it. For one thing, the overall gear ratio was raised (lowered numerically) to facilitate higher speed cruising. The ratio is now 4.70:1 instead of 4.95:1. Then, there’s that lowered compression ratio and quieter, but more restrictive mufflers. There’s been a trade-off, all right, but longer engine life and more rider comfort (less vibration and noise) make the slight sacrifice in acceleration worthwhile.

Engine performance may not be breathtaking, but both handling and braking are. The front brake is a disc, manufactured by Lockheed. It performed faultlessly during our test with only moderate lever pressure being necessary to get full stopping power. The rear brake is the same as last year’s model and is well up to the chore of hauling the T140V down from speed. Of course, the rear brake is the less important of the two in terms of ultimate stopping power, but it performed repeated high speed stops without signs of serious fade.

Handling qualities can only be described as excellent. With one rider on board it was possible to lean the machine to either direction to an acute degree without grounding anything until the rear tire began to step out into a slide. Steering over bumpy curves was precise and reassuring in spite of the lack of a steering damper. Steering geometry felt spot on, too, with no tendency to plow in or understeer in tight corners. Part of this rock steady steering can be attributed to the swinging arm assembly which pivots on bronze bushings and is very strong.

Suspension has a lot to do with this. Front forks are of Triumph design and manufacture and feature two coil springs in compression to control impact forces and integral hydraulic damping to control rebound. Nearly 7 in. of travel is provided by the forks and the spring rate seems ideal for a 160-lb. rider.

Rear suspension is handled by Girling shock absorbers, which are ideally suited to the machine’s weight and intended use. A cam ring at the bottom of each rear shock allows the spring rate to be stiffened for heavier rear passengers or for fast cornering.

Appearance-wise the Triumph is one of the best finished machines to come from England in a long time. Welds on the frame are nearly perfect. Smooth curves begin with the rubber mounted headlamp and continue rearward through the gas tank, seat and taillight. A thoroughly satisfying combination of styling ideas make this one of the most handsome machines on the road. High quality chromium plating and great care in polishing the aluminum alloy engine and clutch covers add touches which the connoisseur will appreciate.

Items which vex us are the handlebars, which force riders to sit bolt upright into the wind, and the Lucas cast aluminum electrical control unit/lever holders. These still have sharp plastic blades which must be flicked up or down to operate the turn signals and dip the headlight beam. And, there are two smaller buttons on each unit, one above and one below the blades. They operate the horn, engine cut-out button, and high-beam flasher for passing. One serves no apparent function. We’d like to see these units restyled.

The electrics are still handled by Lucas and, aside from an initial problem with burned out taillight bulbs because of a reflector which was touching the bulb, transmitting engine vibration to it and causing the filaments to break, we have nothing but the highest praise for the electrical system. The ignition high tension coils are located up under the seat and are mounted in rubber. All components are located so as not to interfere with each other. Wiring is of first quality and the electrical cables running along the handlebars are now attached by attractive chrome-plated clips.

So, there you have it. Better quality control. More power via displacement. A slight increase in performance. And one of the best balanced chassis available anywhere. All told, the T140V is the best Bonneville to date.

TRIUMPH BONNEVILLE

$1599

View Full Issue

View Full Issue