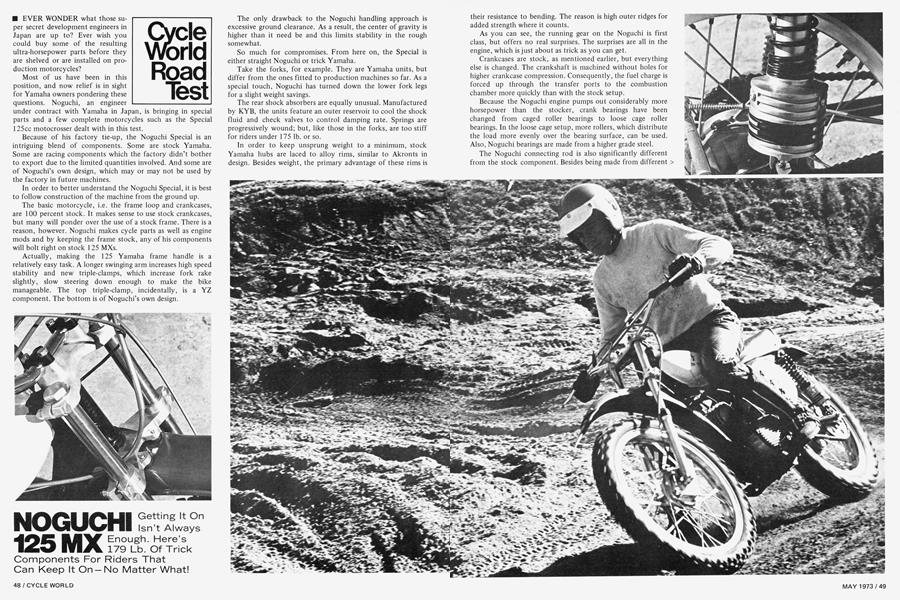

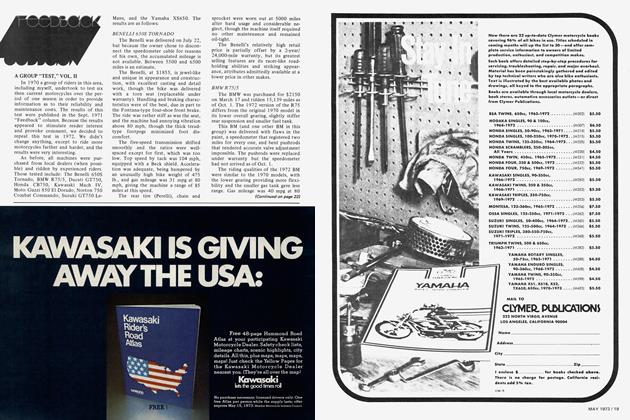

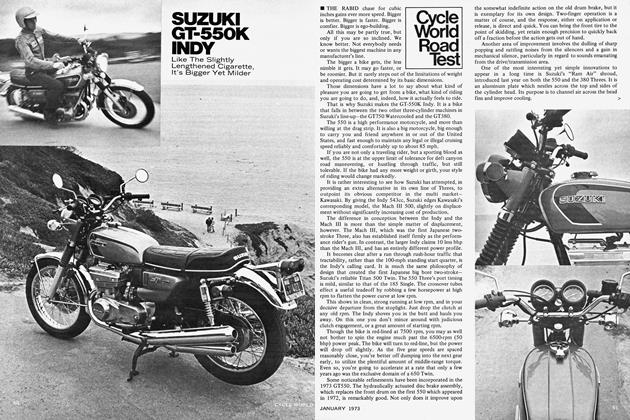

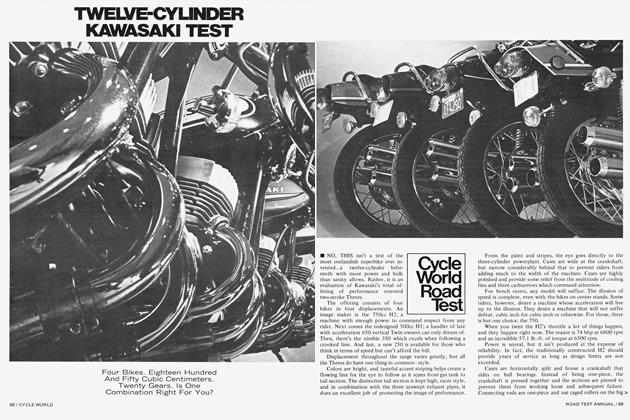

NOGUCHI 125 MX

Cycle World Road Test

Getting It On Isn't Always Enough. Here's 179 Lb. Of Trick Components For Riders That Can Keep It On — No Matter What!

EVER WONDER what those super secret development engineers in Japan are up to? Ever wish you could buy some of the resulting ultra-horsepower parts before they are shelved or are installed on production motorcycles?

Most of us have been in this position, and now relief is in sight for Yamaha owners pondering these questions. Noguchi, an engineer under contract with Yamaha in Japan, is bringing in special parts and a few complete motorcycles such as the Special 125cc motocrosser dealt with in this test.

Because of his factory tie-up, the Noguchi Special is an intriguing blend of components. Some are stock Yamaha. Some are racing components which the factory didn’t bother to export due to the limited quantities involved. And some are of Noguchi’s own design, which may or may not be used by the factory in future machines.

In order to better understand the Noguchi Special, it is best to follow construction of the machine from the ground up.

The basic motorcycle, i.e. the frame loop and crankcases, are 100 percent stock. It makes sense to use stock crankcases, but many will ponder over the use of a stock frame. There is a reason, however. Noguchi makes cycle parts as well as engine mods and by keeping the frame stock, any of his components will bolt right on stock 125 MXs.

Actually, making the 125 Yamaha frame handle is a relatively easy task. A longer swinging arm increases high speed stability and new triple-clamps, which increase fork rake slightly, slow steering down enough to make the bike manageable. The top triple-clamp, incidentally, is a YZ component. The bottom is of Noguchi’s own design.

The only drawback to the Noguchi handling approach is excessive ground clearance. As a result, the center of gravity is higher than it need be and this limits stability in the rough somewhat.

So much for compromises. From here on, the Special is either straight Noguchi or trick Yamaha.

Take the forks, for example. They are Yamaha units, but differ from the ones fitted to production machines so far. As a special touch, Noguchi has turned down the lower fork legs for a slight weight savings.

The rear shock absorbers are equally unusual. Manufactured by KYB, the units feature an outer reservoir to cool the shock fluid and check valves to control damping rate. Springs are progressively wound; but, like those in the forks, are too stiff for riders under 175 lb. or so.

In order to keep unsprung weight to a minimum, stock Yamaha hubs are laced to alloy rims, similar to Akronts in design. Besides weight, the primary advantage of these rims is their resistance to bending. The reason is high outer ridges for added strength where it counts.

As you can see, the running gear on the Noguchi is first class, but offers no real surprises. The surprises are all in the engine, which is just about as trick as you can get.

Crankcases are stock, as mentioned earlier, but everything else is changed. The crankshaft is machined without holes for higher crankcase compression. Consequently, the fuel charge is forced up through the transfer ports to the combustion chamber more quickly than with the stock setup.

Because the Noguchi engine pumps out considerably more horsepower than the stocker, crank bearings have been changed from caged roller bearings to loose cage roller bearings. In the loose cage setup, more rollers, which distribute the load more evenly over the bearing surface, can be used. Also, Noguchi bearings are made from a higher grade steel.

The Noguchi connecting rod is also significantly different from the stock component. Besides being made from different > material, the Noguchi rod is slotted at the big end for better lubrication of the loose cage roller bearing.

There isn’t anything trick about the top end of the rod or the wrist pin, but the piston is another Noguchi item. Not only are the windows necessary for reed valve induction considerably larger than stock, but the piston skirt has been reshaped to take advantage of the radical port timing. A single Dykes ring completes the piston assembly.

The barrel is a special casting built to Noguchi specifications. The bore is chromed for optimum wear and ports are polished for optimum flow characteristics.

Two cylinder heads are available. Both a sunburst design and the conventional looking item fitted to our test machine offer increased cooling over stock, and both yield identical compression ratios. Performance, in other words, is identical with either head as long as engine temperature remains constant. Because of its marginal edge in cooling surface, the sunburst unit is a better buy for hot climates.

Radical port timing has also necessitated a change in the intake system. For one thing, the reed valve assembly is considerably larger than stock even though it sports a similar four petal design. Complimenting this is a 28mm Mikuni (2mm larger than stock) that has been further modified by Noguchi. The exact modification is not known, but the Noguchi carb does allow easy starting and “clean” running throughout the rev range. Considering the engine’s high state of tune, this is fantastic.

In order to ensure reliability in the 8500 rpm bracket, where the Noguchi develops maximum power, it is a good idea to replace the stock flywheel magneto (the rivets work loose if quick shifts are executed repeatedly at near maximum rpm) with a Yamaha inner-rotor magneto. The inner-rotor mag is used with the stock MX flywheel, resulting in very little flywheel effect to smooth out power delivery.

Taken in total, Noguchi engine modifications account for a claimed 55 percent power increase over stock. While substantial horsepower gains are neat, they are never achieved without some sort of sacrifice. In this case, power output from mid rpm down has been reduced significantly; so significantly, in fact, that the Noguchi wouldn’t be ridable without a sturdy clutch and close-ratio, five-speed transmission.

Like we said, the Noguchi is a breakthrough as far as offering trick components to the public is concerned. But, before you decide that this is the best way to improve your lap times, realize one thing. It takes an expert to ride the Noguchi properly. Here’s why.

If you don’t have your weight well forward, the sudden power surge at around 7000 rpm will force wheelies in any of the bottom three gears. Constant gear shifting and buzzing the engine is the only way to avoid them. Lose your concentration for one second, and it’s all over. Bog or wheelie. It doesn’t matter. Either will let the competition by.

The rougher the course, or the tighter the turns, the harder it is to ride the Noguchi properly. And, unfortunately, the suspension doesn’t help much either in its delivered state of tune.

Spring rate at both ends is simply too stiff for riders under 175 lb. and this causes the bike to hop around a good deal. Damping is excellent, however, so a little fine tuning should solve this problem completely.

If you’re the kind of pilot that has the ability to keep a bike turned on no matter what, the Noguchi should provide a one-way ticket to victory. There just isn’t anything around that can match it in the horsepower department.

If you tend to lean toward smoother courses, TTs or short track events, the Noguchi is totally suitable for any rider with ability—as delivered.

So, make a decision—ultimate horsepower or tractability. If you choose the former, Noguchi products should be near the top of your check list. |g

NOGUCHI 125 MX

$1095