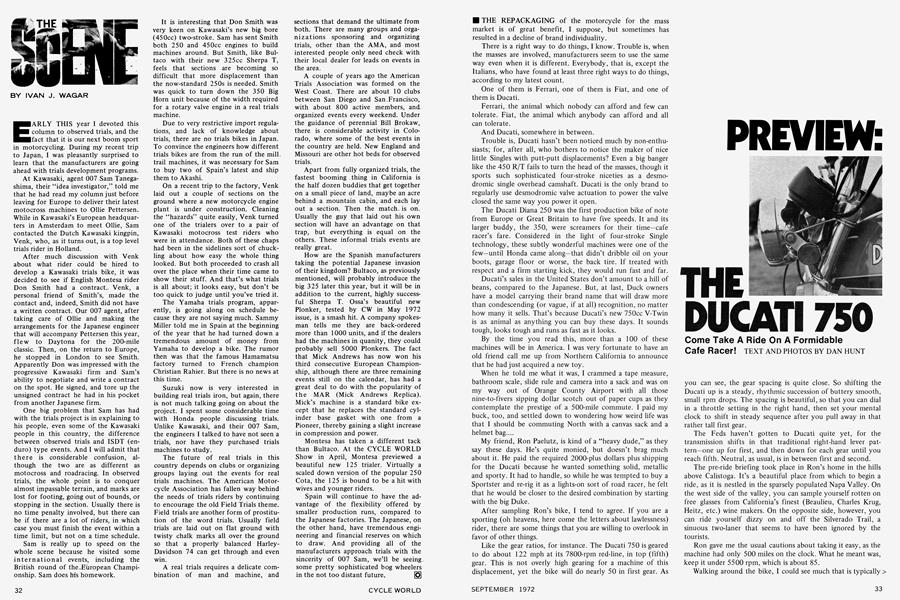

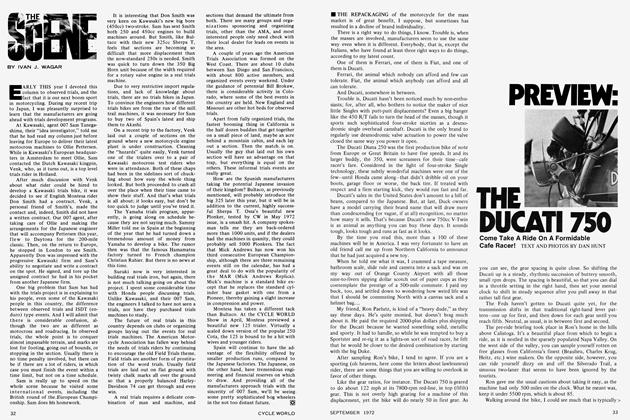

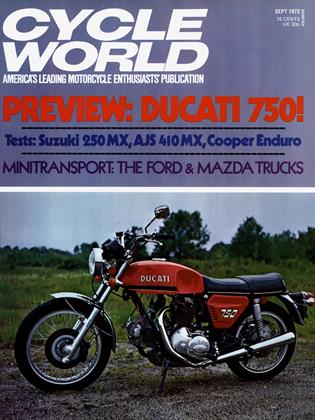

THE DUCATI 750

PREVIEW:

Come Take A Ride On A Formidable Cafe Racer!

DAN HUNT

THE REPACKAGING of the motorcycle for the mass market is of great benefit, I suppose, but sometimes has resulted in a decline of brand individuality.

There is a right way to do things, I know. Trouble is, when the masses are involved, manufacturers seem to use the same way even when it is different. Everybody, that is, except the Italians, who have found at least three right ways to do things, according to my latest count.

One of them is Ferrari, one of them is Fiat, and one of them is Ducati.

Ferrari, the animal which nobody can afford and few can tolerate. Fiat, the animal which anybody can afford and all can tolerate.

And Ducati, somewhere in between.

Trouble is, Ducati hasn’t been noticed much by non-enthusiasts; for, after all, who bothers to notice the maker of nice little Singles with putt-putt displacements? Even a big banger like the 450 R/T fails to turn the head of the masses, though it sports such sophisticated four-stroke niceties as a desmodromic single overhead camshaft. Ducati is the only brand to regularly use desmodromic valve actuation to power the valve closed the same way you power it open.

The Ducati Diana 250 was the first production bike of note from Europe or Great Britain to have five speeds. It and its larger buddy, the 350, were screamers for their time—cafe racer’s fare. Considered in the light of four-stroke Single technology, these subtly wonderful machines were one of the few—until Honda came along—that didn’t dribble oil on your boots, garage floor or worse, the back tire. If treated with respect and a firm starting kick, they would run fast and far.

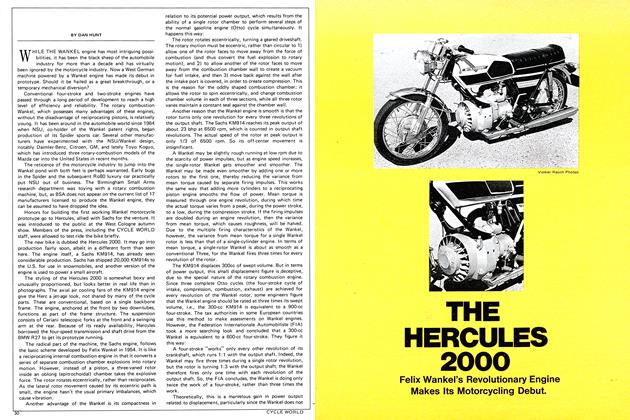

Ducati’s sales in the United States don’t amount to a hill of beans, compared to the Japanese. But, at last, Duck owners have a model carrying their brand name that will draw more than condescending (or vague, if at all) recognition, no matter how many it sells. That’s because Ducati’s new 750cc V-Twin is as animal as anything you can buy these days. It sounds tough, looks tough and runs as fast as it looks.

By the time you read this, more than a 100 of these machines will be in America. I was very fortunate to have an old friend call me up from Northern California to announce that he had just acquired a new toy.

When he told me what it was, I crammed a tape measure, bathroom scale, slide rule and camera into a sack and was on my way out of Orange County Airport with all those nine-to-fivers sipping dollar scotch out of paper cups as they contemplate the prestige of a 500-mile commute. I paid my buck, too, and settled down to wondering how weird life was that I should be commuting North with a canvas sack and a helmet bag....

My friend, Ron Paelutz, is kind of a “heavy dude,” as they say these days. He’s quite monied, but doesn’t brag much about it. He paid the required 2000-plus dollars plus shipping for the Ducati because he wanted something solid, metallic and sporty. It had to handle, so while he was tempted to buy a Sportster and re-rig it as a lights-on sort of road racer, he felt that he would be closer to the desired combination by starting with the big Duke.

After sampling Ron’s bike, I tend to agree. If you are a sporting (oh heavens, here come the letters about lawlessness) rider, there are some things that you are willing to overlook in favor of other things.

Like the gear ratios, for instance. The Ducati 750 is geared to do about 122 mph at its 7800-rpm red-line, in top (fifth) gear. This is not overly high gearing for a machine of this displacement, yet the bike will do nearly 50 in first gear. As you can see, the gear spacing is quite close. So shifting the Ducati up is a steady, rhythmic succession of buttery smooth, small rpm drops. The spacing is beautiful, so that you can dial in a throttle setting in the right hand, then set your mental clock to shift in steady sequence after you pull away in that rather tall first gear.

The Feds haven’t gotten to Ducati quite yet, for the transmission shifts in that traditional right-hand lever pattern-one up for first, and then down for each gear until you reach fifth. Neutral, as usual, is in between first and second.

The pre-ride briefing took place in Ron’s home in the hills above Calistoga. It’s a beautiful place from which to begin a ride, as it is nestled in the sparsely populated Napa Valley. On the west side of the valley, you can sample yourself rotten on free glasses from California’s finest (Beaulieu, Charles Krug, Heitz, etc.) wine makers. On the opposite side, however, you can ride yourself dizzy on and off the Silverado Trail, a sinuous two-laner that seems to have been ignored by the tourists.

Ron gave me the usual cautions about taking it easy, as the machine had only 500 miles on the clock. What he meant was, keep it under 5500 rpm, which is about 85.

Walking around the bike, I could see much that is typically > Ducati. Like the finned, deep, 10 pt. capacity oil sump. This seems large, but perhaps Ducati feels that it must circulate that amount of oil to counteract any possible inadequacies in air-cooling imposed by the rearward position of the No. 2 cylinder barrel.

This engine is a 90-degree V-Twin and, as the front pot is nearly horizontal, the rear cylinder receives a fair amount of air circulation compared to the H-D V-Twin, which has only 45 degrees between fairly upright barrels. Italy’s other 90-degree Twin is the Moto Guzzi, and it avoids the cooling problem entirely by turning the engine so that both barrels are in the airstream and using shaft drive.

Ducati’s philosophy is the more sporting of the two, for it allows use of slightly more efficient rear chain drive and presents a very narrow engine profile for the rider. The center of gravity is quite low, because of the forward cant of the front cylinder barrel. You can argue all day about the fact that you’ll never drag the pots on a shaftie like the Guzzi or BMW, or the cases on an in-line transverse Four, but you’ll never convince me that the guy with the narrowest and lowest engine doesn’t have at least a psychological advantage in the corners.

There are certain trade-offs in Ducati’s choice, however. The fouling and shielding of a clean blast of air to a V-Twin’s rear cylinder may be counteracted by superlative oil capacity and circulation which Ducati obviously has. But Ducati, having chosen 750cc and 90-degree cylinder disposition, must cope with a rather long wheelbase—60.2 in.

You can make anything handle well if you work at it, but that 60.2 in. will tend to slow the machine’s steering responsiveness. The Norton Commando 750, another individualized vertical Twin answer to the problem of going fast, stopping and turning corners in neat fashion, has only a 57-in. wheelbase, and even Harley’s lOOOcc Sportster manages to hold the wheelbase to 58.5 in., probably because of its smaller cylinder angle. There is, after all, only so much room, per a given rake and wheel size, between front axle and swinging arm. The Ducati uses it all.

The V-Twin concept, of course, has a great history to it. As far back as there were big motorcycles, there were big V-Twins. Harley, Indian, Big X, Vincent HRD, etc. Designers glommed on to the V-Twin for the ergonomic reasons we have already outlined and then for more subtle reasons. When they tried to improve on the V and build Fours (Ace, Henderson, etc.), they found their technology wasn’t good enough to make the Fours acceptable, reliable or even profitably producible.

So the V held on, reviled by some for its grossness and staggered firing pattern, and yet loved by many more for its relative simplicity and even its raw look of bigness. The technical reason for the V is its theoretical superiority of mechanical balance over the parallel Twin in which the pistons run up and down in unison. This sort of parallel Twin is hardly better than a big shaky Single.

Yet the V-Twin, especially in the 90-degree configuration, offers the promise of total elimination of primary imbalance. There is left a secondary component that averages out a nearly horizontal reciprocating thrust in line with the machine, but hopefully the elimination of primary imbalance will suppress those strong resonating impulses which course through the motorcycle frame and mysteriously crack fender mounts and the like.

If all the theory in the world won’t sway you that you can build a relatively vibration-free V-Twin, you’re right. When I fired up Ron’s Duke, after an inexperienced tickle and four nerve-racking kicks, it settled down to that gorgeous staggered > lope like every other V-Twin I’ve ever ridden. That is, the bars tremble and your butt jiggles, letting you know that there is one big, bad machine churning away underneath you. A machine.

While the Ducati was warming, I was briefed on the controls. The white light on the non-glare, rough finished black instrument nacelle tells you the ignition key—in a clumsy spot under your left thigh—is on. The green light on the right says you’re parking lights are on, and the left hand red one indicates high beam is operating. They haven’t bothered to translate the light functions for the American consumer and so these lights are labeled with abbreviated spaghetti, “Gen., Abb., Luci,” just like when you go to Modena to pick up one of Enzo’s creations. The light switch is also on this nacelle, which carries a brace of Smiths instruments; these are in English and mph. In general, the switches are of mediocre quality.

This part of the instrument package is neat, but the issue is confused by the startling use of chromed, heavy-gauge spring wire to mount the headlight. A proper guess is that use of the wire makes it very easy to mount short racing bars on the fork tubes where they’re supposed to be, without disturbing the light brackets.

The speedometer and tachometer are individually lit and this street racer even has turn signal pods. The control cables and the wiring for all these lighting conveniences are not disguised well, and could stand some studious taping and rerouting, or, in the case of the turn signals, simple removal. The indicators might as well be removed, as no one, including Ducati, has yet figured out a turn signal that is convenient to operate and self-explanatory in operation. The car makers use a stalk, knowing that a proper driver makes frequent use of the indicator when in traffic. Thumb switches on bikes are awkward. Perhaps a twist-operated spring-return two-way switch in the left-hand grip is the answer.

The seat of the Ducati 750 is typically Italian and thus is stiff, even if it is quite wide. Its saving grace is that its width is matched with the slightly scalloped fuel tank, so that, when you take off, your knees come together naturally to a firm comfortable grip on the tank. Underneath, if you have the patience or motivation for the unscrewing ritual, is a large tool tray with a shoddy looking assortment of stamped tools. Quick replacement of the seat is directly contingent on how sly you are in fitting it to two alignment rods on the frame. Neither Ron nor I were very sly, it seems.

Fiberglass is used for the fuel tank and side panels, and the finish is attractive but poorly executed. There are small pinholes in the gel coat. This is nothing new, for the fiberglass tank on the Ducati 450 R/T we tested had the same level of finish. One improvement is that, unlike the 450, the 750’s gasoline petcocks are easily accessible.

I pulled off gingerly and idled down the hill. Ron fell in behind on this fantastic old Fifties Triumph Twin with rigid frame that he’d bought for $50. It was a spare bike to keep at his vacation home, and he’d been running it for two years straight with little more than an occasional oil change.

The Ducati was surprisingly easy-going at crawling speeds. At 32 in., the seat isn’t very high, so the bike is no chore to handle at a stoplight. And, as soon as it’s moving at all, it self-stabilizes in a gyroscopic feel reminiscent of a Harley 74 or BMW. One reason for this pleasing behavior is that low center of gravity afforded by the oil sump and nearly horizontal front cylinder. In a way, it’s the same thing that made the H-D Aermacchi Sprint such an incredible handler.

In spite of a set of formidable valve timing specifications, Ducati’s single cammer pulls off from a stop neatly with no jerking and runs well at slow speeds. The abovementioned timing includes a great deal of overlap. The figures are: inlet opens 65-deg. btc, closes 84-deg. abc, with a specified tappet clearance of 0.0020 to 0.0039 in.; exhaust opens 80-deg. bbc and closes 58-deg. ate, with tappet clearances of 0.0039 to 0.0059 in. This yields an overlap figure of 123 degrees, equivalent to a fairly ratty Norton Manx road racer. Most big bore road bikes for sporting use have more moderate overlap— usually in the 80s or low 90s—assuming that the machines will not be used at high rpm most of the time.

The mitigating factors in this case are the use of moderate 8.5:1 compression ratio and conservative 30mm carburetor choke sizè. The reason that Ducati uses wild cam timing has to do with that “other” model—the production racer designed to drub MVs at Imola, turning an impressive 9000 rpm all the while. So the machine runs in reasonably docile fashion, albeit yielding unimpressive fuel consumption between 30 and 35 mpg. Overlap wastes a lot of gasoline.

Once we reached the Silverado trail and pointed ourselves toward Napa, I got an indication of what a fine roadster this is. It’s what the Italians call “gambelunghe,” or long legs. After a brief period of marked vibration at about 4200 rpm, it settles down and wants to go fast. Without a lot of busy work. Singles have that quality, as do BMWs and properly geared Nortons and Harleys. Now you can add Ducati to the list.

The bike stops and soaks up road undulations well. The classic test in the Napa Valley is to leave the Silverado trail at the Lake Berryessa road and zoom up a narrow canyon road straight out of the mountain climb at the Isle of Man. The road is smooth but swervy until you pass a reservoir and switch right into Lobo Canyon. The first section tells you about brakes, because you have to actuate them while the bike is heeled over. The second section gives you more of the same, but tighter, and also tries to smash your forks up through your teeth.

The Ducati feels properly stiff without being rock hard. In spite of the long wheelbase, the bike showed little tendency to plow in the 45 to 60 stuff. It is, after all, relatively light at less than 440 lb. The front disc brake is quite strong, but is easy to control delicately. Lever travel diminishes greatly once the pucks are gripping the disc, but it is still possible to feel how much more or less pressure is needed. On rough pavement or during heavy braking, the Ducati doesn’t heave as you might expect some machines of this size category to do. My sole complaint has to do with the narrowness of the tires, particularly the back one. Granted they track well, but with the horsepower that this 750 develops, Ducati would do well to go to one of the larger super-compound tires developed for the Japanese big bores. As for the front tire, a larger width based on a road racing design may be necessary to eliminate possible plowing arising when bike is pushed really hard.

The handlebars are overly wide for spirited riding, and not too appropriate to the bike’s natural proportion. The megaphone-styled but relatively quiet silencers are raked nicely upward to provide excellent turning clearance. The first place you’ll hit when turning left is the center stand.

Due to the newness of the machine and the lack of a dragstrip nearby, I can’t give you concrete acceleration figures. But a glance at the computed speeds in the various gear ratios will be revealing. I think the bike is geared quite honestly.

The gearing figures will also tell you that this machine is not a drag bike in delivered form. If you want that, you’ll be better off with a Kawasaki 750 or even the Norton 750. My computations tell me that the Ducati will do a quarter mile in no better than the middle or high 13s, and will run through the traps at about 95 to 97 mph. Regearing would help the e.t. considerably, but not change the trap speed much.

The man who deserves to own a Ducati 750 will not be speculating about this sort of straight-line statistic, anyway.

For a Ducati owner, the shortest distance between two points is a curved line.

DUCATI 750

$1995

View Full Issue

View Full Issue