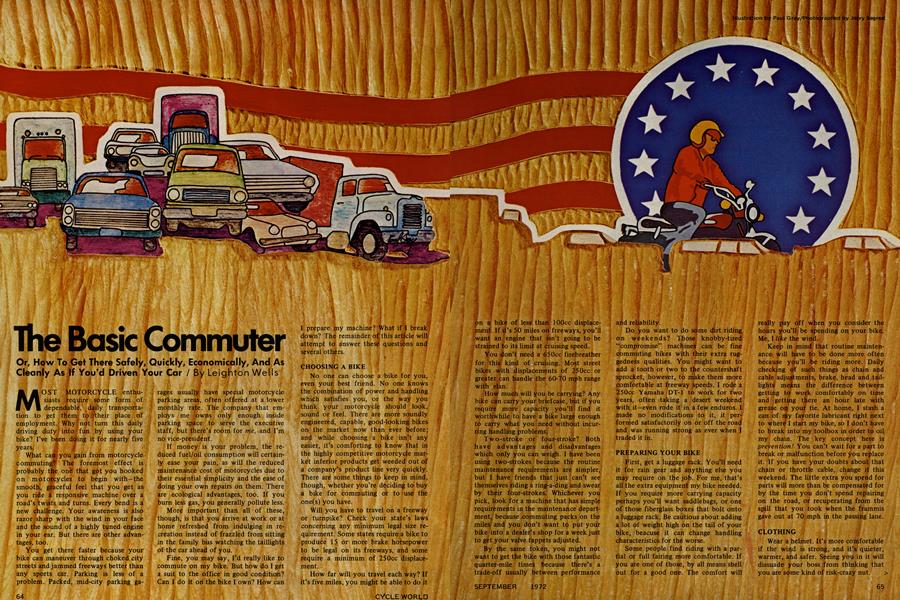

The Basic Commuter

FEATURES

Or, How To Get There Safely, Quickly, Economically, And As Cleanly As If You’d Driven Your Car

Leighton Wells

MOST MOTORCYCLE enthusiasts require some form of dependable, daily transportation to get them to their place of employment. Why not turn this daily driving duty into fun by using your bike? I’ve been doing it for nearly five years.

What can you gain from motorcycle commuting? The foremost effect is probably the one that got you hooked on motorcycles to begin with—the smooth, graceful feel that you get as you ride a responsive machine over a road’s twists and turns. Every bend is a new challenge. Your awareness is also razor sharp with the wind in your face and the sound of a highly tuned engine in your ear. But there are other advantages, too.

You get there faster because your bike can maneuver through choked city streets and jammed freeways better than any sports car. Parking is less of a problem. Packed, mid-city parking ga-

rages usually have special motorcycle parking areas, often offered at a lower monthly rate. The company that employs me owns only enough inside parking space to serve the executive staff, but there’s room for me, and I’m no vice-president.

If money is your problem, the reduced fuel/oil consumption will certainly ease your pain, as will the reduced maintenance cost of motorcycles due to their essential simplicity and the ease of doing your own repairs on them. There are ecological advantages, too. If you burn less gas, you generally pollute less.

More important than all of these, though, is that you arrive at work or at home refreshed from indulging in recreation instead of frazzled from sitting in the family bus watching the taillights of the car ahead of you.

Fine, you may say, I’d really like to commute on my bike. But how do I get a suit to the office in good condition? Can I do it on the bike I own? How can

I prepare my machine? What if I break down? The remainder of this article will attempt to answer these questions and several others.

CHOOSING A BIKE

No one can choose a bike for you, even your best friend. No one knows the combination of power and handling which satisfies you, or the way you think your motorcycle should look, sound or feel. There are more soundly engineered, capable, good-looking bikes on the market now than ever before; and while choosing a bike isn’t any easier, it’s comforting to know that in the highly competitive motorcycle market inferior products get weeded out of a company’s product line very quickly. There are some things to keep in mind, though, whether you’re deciding to buy a bike for commuting or to use the one(s) you have.

Will you have to travel on a freeway or turnpike? Check your state’s laws concerning any minimum legal size requirement. Some states require a bike to produce 15 or more brake horsepower to be legal on its freeways, and some require a minimum of 250cc displacement.

How far will you travel each way? If it’s five miles, you might be able to do it on a bike of less than lOOcc displacement. If it’s 50 miles on freeways, you’ll want an engine that isn’t going to be strained to its limit at cruising speed.

You don’t need a 650cc firebreather for this kind of cruising. Most street bikes with displacements of 250cc or greater can handle the 60-70 mph range with elan.

How much will you be carrying? Any bike can carry your briefcase, but if you require more capacity you’ll find it worthwhile to have a bike large enough to carry what you need without incurring handling problems.

Two-stroke or four-stroke? Both have advantages and disadvantages which only you can weigh. I have been using two-strokes because the routine maintenance requirements are simpler, but I have friends that just can’t see themselves riding a ring-a-ding and swear by their four-strokes. Whichever you pick, look for a machine that has simple requirements in the maintenance department, because commuting packs on the miles and you don’t want to put your bike into a dealer’s shop for a week just to get your valve tappets adjusted.

By the same token, you might not want to get the bike with those fantastic quarter-mile times because there’s a trade-off usually between performance and reliability.

Do you want to do some dirt riding on weekends? Those knobby-tired “compromise” machines can be fine commuting bikes with their extra ruggedness qualities. You might want to add a tooth or two to the countershaft sprocket, however, to make them more comfortable at freeway speeds. I rode a 250cc Yamaha DT-1 to work for two years, often taking a desert weekend with it—even rode it in a few enduros. I made no modifications to it, it performed satisfactorily on or off the road and was running strong as ever when I traded it in.

PREPARING YOUR BIKE

First, get a luggage rack. You’ll need it for rain gear and anything else you may require on the job. For me, that’s all the extra equipment my bike needed. If you require more carrying capacity perhaps you’ll want saddlebags, or one of those fiberglass boxes that bolt onto a luggage rack. Be cautious about adding a lot of weight high on the tail of your bike, beacuse it can change handling characteristics for the worse.

Some people find riding with a partial or full fairing more comfortable. If you are one of those, by all means shell out for a good one. The comfort will really pay off when you consider the hours you’ll be spending on your bike. Me, I like the wind.

Keep in mind that routine maintenance will have to be done more often because you’ll be riding more. Daily checking of such things as chain and cable adjustments, brake, head and taillights means the difference between getting to work comfortably on time and getting there an hour late with grease on your tie. At home, I stash a can of my favorite lubricant right next to where I start my bike, so I don’t have to break into my toolbox in order to oil my chain. The key concept here is prevention! You can’t wait for a part to break or malfunction before you replace it. If you have your doubts about that chain or throttle cable, change it this weekend. The little extra you spend for parts will more than be compensated for by the time you don’t spend repairing on the road, or recuperating from the spill that you took when the frammis gave out at 70 mph in the passing lane.

CLOTHING

Wear a helmet. It’s more comfortable if the wind is strong, and it’s quieter, warmer, and safer. Seeing you in it will dissuade your boss from thinking that you are some kind of risk-crazy nut. >

Use good eye protection devices—a face shield, good goggles or the like—to prevent “early morning red-eye,” or worse, being bashed by a grasshopper or a piece of flying gravel. I wear contact lenses to work, rendering me particularly sensitive to dust and grit in my eyes. The best headgear I’ve found for me is a popular brand full coverage helmet, the kind many racers use. I’ve had it for a year, and have yet to get any grit in my eye.

The rest of your clothing choices will be profoundly influenced by what you want to wear (or what you can get away with wearing) at the office. Students and mechanics don’t have a problem. If you’re an office worker, as I am, recent style trends toward boots of ankle height or higher, and jean-like or flared pants are greatly in your favor.

In my company, nearly everyone wears a sport jacket and slacks when he arrives, hangs up his jacket and works the entire day in his shirt sleeves. I haven’t worn a sport jacket in for years and I don’t think anyone’s noticed. If you must wear a suit, you have two options. You can wear a motorcycle jacket in transit, putting your suit jacket on your luggage rack (preferably protected from the elements by some container) or you can invest in one of the fine British riding suits. The British, whose insistance on proper dress is well known, have got the suit problem well in hand.

For riding gear, you have to ask “What sort of weather conditions am I likely to encounter?” and buy accordingly. For those hot summer months I wear a light leather jacket and thin pigskin dress gloves. Pigskin wears like iron, shrivels up to fit your hand, and is extremely soft and pliable. Personally, I wouldn’t drive without gloves, but you may find them unnecessary.

During the colder months of the year, by which I mean temperatures down to about 25 degrees, I switch to an old-fashioned Marlon Brando-type black leather jacket which has quilted nylon padding, and leather mittens. That jacket style was developed to offer maximum wind protection to the cyclist; if you ride in cold weather, it is a fine way to go. Its sleeves have wrist zippers which cut off any airflow up the arms, closing the front zipper overlaps two generous lapel flaps tightly enough to prevent wind entering at the neck, and the jacket has a belt to keep the waist area tight. Many Army-Navy surplus stores sell them, and nothing else works as well. If only they made them in mottled beige so I didn’t look like a Wild One....

Cold weather glove choice is crucial for both comfort and safety. I’ve found

that if you can keep hands, feet and torso warm, you’ll feel warm even if your shins register freezing. So far, the best handgear I’ve found is sold by L. L. Bean, Inc., Freeport, Maine, and called “Snow-Mobile Mitts.” They have an outer layer of cowhide and are insulated by acrylic pile bonded to foam. They’re warm in any wind at any temperature, and the gauntlet part runs six inches up the arm with an elastic closure. They are listed in the Fall ’71 catalog for $11.75 postpaid, a rare bargain. At truly cold temperatures, gloves which separate the fingers just don’t keep you warm enough.

RAINGEAR

Nobody wants to ride in the rain, but if you’re at work and a downpour starts that looks like it won’t let up, it’s nice to be prepared. My raingear is a set of inexpensive yellow Japanese oilskins (six or seven bucks in any surplus store) and a pair each of sox and tennis shoes. I use the tennis shoes for riding and let my office shoes stay dry and comfortable. Using this gear I’ve gotten to work dryer than people who have driven to work but walked a block between their car and the office door. Folded up, the raingear uses little more space than a standard lunch box. I’ll talk about rain some more later on when we get to driving techniques.

SPECIAL EQUIPMENT

If you elect to equip your bike with only a luggage rack, as I have, you will want some light bag to strap to it to hold your odds and ends. I have found that a canvas bag like the ones athletes carry their sox and uniforms in works well. The bags are cheap, don’t mind getting wet, and have a lot of space.

You will want to carry a more complete tool kit than is usually supplied with a bike, because you don’t want to get stranded.

I’ve outfitted myself with the parts I’d take if I were going on any lengthy trip: extra plugs, some tape and safety wire, an extra taillight bulb, a file for my points and a tiny (4 in.) adjustable wrench. The latter has bailed me out often, when the cheap, pressed steel tools supplied with most bikes have proven to be too weak, or mis-sized or otherwise inadequate.

Some sort of cable or chain lock is a good idea. It won’t stop the professional thief, but it deters the amateur, and gives you a way to lock your helmet to your bike, avoiding the hassle of finding a place to stow it in your work area. I’ve been thinking of buying a helmet radio to complete my outfit, but I’ve been putting it off until someone tells me how it affects helmet performance in a crash. Usually the day-to-day happenings on the road are entertainment enough.

DRIVING TECHNIQUES

You have probably been riding a motorcycle for some time if you are considering commuting. If you are new to the sport, I’d suggest that you take a few months of practice on less congested roads or dirt before you attempt commuting, because survival on a crowded highway demands quick, sure responses from a motorcyclist. If you have to think for a second when deciding whether or not to use your front brake, or if you sometimes shift when you meant to activate your rear brake, you’re not ready. A month or two of more leisurely riding will have you feeling “at one” with your mount.

I find that it helps if you consider yourself invisible. If you are convinced that no one on the road sees you, you’ll always be ready for the guy who’s going to change into your freeway lane right on top of you, or pull out from that stop sign directly into your path. These drivers are all around us, but they’re no problem if you know they don’t see you. The exception to this idea, of course, is law enforcement personnel, who can see in the dark.

On jammed-up freeways and surface streets there is a great temptation to move between lanes of slower moving cars. In California this is called “cutting traffic” and is legal (or at least condoned) on freeways and illegal on the narrower surface streets. Should you do it? My advice, if it’s legal in your state, is a cautious yes. The motorcyclist who is between lanes can see a long way up the dozens of rear end collisions. Traction is better, too, because the center of each lane usually has a slick of crankcase oil on it that the edges don’t have. If you elect to cut traffic, there are two things to keep in mind. First, relative speed. Never go more than 5-10 mph faster than the cars around you.

Highway patrolmen have told me that slower traffic seems to bring about faster lane changes, that car drives will swerve rapidly to get into tiny hole in a lane which is moving only slightly faster, and therefore, patrolmen reduce their relative speed as traffic slows.

Second, an escape route. Of course, car drivers don’t see you (you’re invisible, remember?), but they see other cars. A car will only change lanes if there’s an opening in the lane to which he’s moving. The cautious motorcyclist is constantly asking himself “Where do I go if this fellow on my right/left starts a lane change in my direction?” Generally, if there’s a hole for the car, you can find one, too, by making the lane change with the car and ending up between lanes again. If you don’t see any escape route, you shouldn’t get in between the lanes.

Traveling on the right or left hand shoulders, the so-called “breakdown lanes,” is never a good idea. The area is often littered with old hubcaps and mufflers to trip you up, and is likely at any moment to be used by a car half out of control from a blowout or other mechanical problem.

Driving in rain is a specialized skill. It can be done, but is never as safe as driving in dry weather. Your front brake

must be used with caution in the wet, due to the risk of locking it up and losing all control. This reduces your straight line stopping ability considerably, because your weight shifts to your front wheel during deceleration. With traction a problem, your maneuvering ability (the best protection you have) is also reduced, so no cutting traffic in the rain. Drivers’ vision is further reduced, so now even other cars are sometimes invisible. So if you must ride in rain, maintain as great a distance as possible from cars in front and in back of you, and redouble your concentration on possible escape routes. Often surface streets, with their slower speeds, are better bets in rain.

Snow: No go. I was once caught 16 miles from home on Long Island, New York, at the start of a blizzard. I was in school at the time, and six inches of snow had fallen before I knew it was snowing. The resulting experience makes a great yarn, but if I were caught in the same situation again, I would sell my bike at 20 cents on the dollar and charter a helicopter home rather than repeat the experience.

Well, there it is. Armed with this knowledge, and with a modest investment in good equipment, you can start enjoying that drive to work.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue