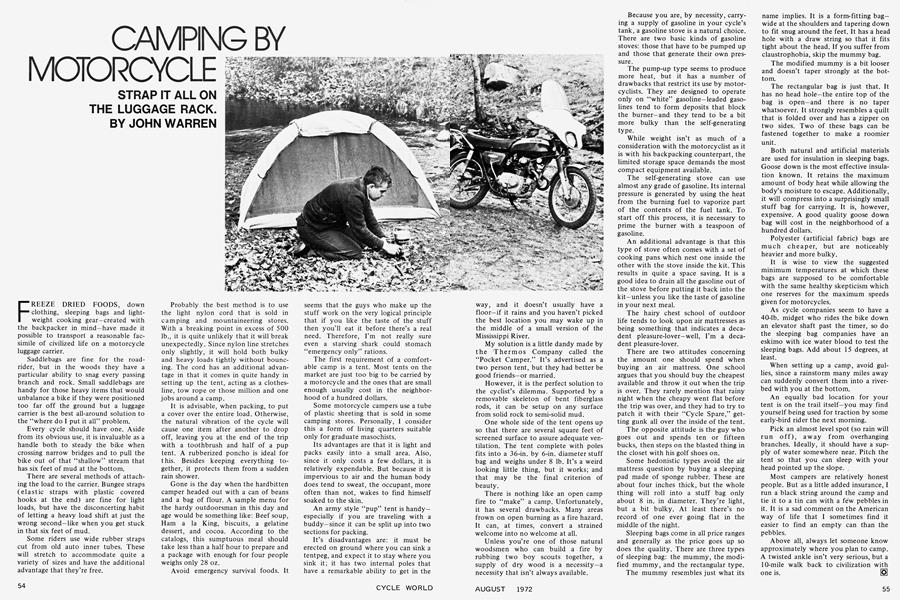

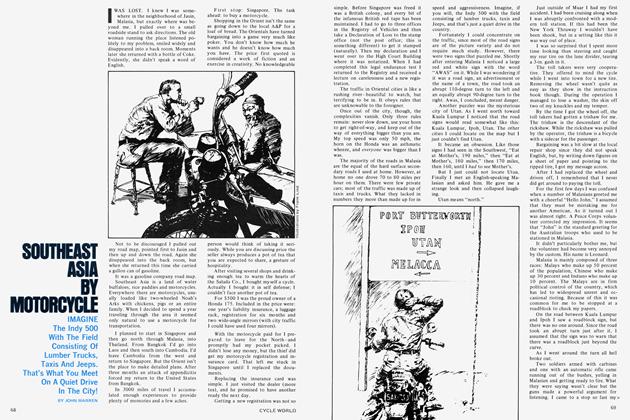

CAMPING BY MOTORCYCLE

STRAP IT ALL ON THE LUGGAGE RACK.

JOHN WARREN

FREEZE DRIED FOODS, down clothing, sleeping bags and light-weight cooking gear-created with the backpacker in mind-have made it possible to transport a reasonable fac-simile of civilized life on a motorcycle luggage carrier.

Saddlebags are fine for the roadrider, but in the woods they have a particular ability to snag every passing branch and rock. Small saddlebags are handy for those heavy items that would unbalance a bike if they were positioned too far off the ground but a luggage carrier is the best all-around solution to the “where do I put it all” problem.

Every cycle should have one. Aside from its obvious use, it is invaluable as a handle both to steady the bike when crossing narrow bridges and to pull the bike out of that “shallow” stream that has six feet of mud at the bottom.

There are several methods of attaching the load to the carrier. Bungee straps (elastic straps with plastic covered hooks at the end) are fine for light loads, but have the disconcerting habit of letting a heavy load shift at just the wrong second—like when you get stuck in that six feet of mud.

Some riders use wide rubber straps cut from old auto inner tubes. These will stretch to accommodate quite a variety of sizes and have the additional advantage that they’re free.

Probably the best method is to use the light nylon cord that is sold in camping and mountaineering stores. With a breaking point in excess of 500 lb., it is quite unlikely that it will break unexpectedly. Since nylon line stretches only slightly, it will hold both bulky and heavy loads tightly without bouncing. The cord has an additional advantage in that it comes in quite handy in setting up the tent, acting as a clothesline, tow rope or those million and one jobs around a camp.

It is advisable, when packing, to put a cover over the entire load. Otherwise, the natural vibration of the cycle will cause one item after another to drop off, leaving you at the end of the trip with a toothbrush and half of a pup tent. A rubberized poncho is ideal for this. Besides keeping everything together, it protects them from a sudden rain shower.

Gone is the day when the hardbitten camper headed out with a can of beans and a bag of flour. A sample menu for the hardy outdoorsman in this day and age would be something like: Beef soup, Ham a la King, biscuits, a gelatine dessert, and cocoa. According to the catalogs, this sumptuous meal should take less than a half hour to prepare and a package with enough for four people weighs only 28 oz.

Avoid emergency survival foods. It seems that the guys who make up the stuff work on the very logical principle that if you like the taste of the stuff then you’ll eat it before there’s a real need. Therefore, I’m not really sure even a starving shark could stomach “emergency only” rations.

The first requirement of a comfortable camp is a tent. Most tents on the market are just too big to be carried by a motorcycle and the ones that are small enough usually cost in the neighborhood of a hundred dollars.

Some motorcycle campers use a tube of plastic sheeting that is sold in some camping stores. Personally, I consider this a form of living quarters suitable only for graduate masochists.

Its advantages are that it is light and packs easily into a small area. Also, since it only costs a few dollars, it is relatively expendable. But because it is impervious to air and the human body does tend to sweat, the occupant, more often than not, wakes to find himself soaked to the skin.

An army style “pup” tent is handy— especially if you are traveling with a buddy—since it can be split up into two sections for packing.

It’s disadvantages are: it must be erected on ground where you can sink a tentpeg, and expect it to stay where you sink it; it has two internal poles that have a remarkable ability to get in the way, and it doesn’t usually have a floor—if it rains and you haven’t picked the best location you may wake up in the middle of a small version of the Mississippi River.

My solution is a little dandy made by the Thermos Company called the “Pocket Camper.” It’s advertised as a two person tent, but they had better be good friends—or married.

However, it is the perfect solution to the cyclist’s dilemma. Supported by a removable skeleton of bent fiberglass rods, it can be setup on any surface from solid rock to semi-solid mud.

One whole side of the tent opens up so that there are several square feet of screened surface to assure adequate ventilation. The tent complete with poles fits into a 36-in. by 6-in. diameter stuff bag and weighs under 8 lb. It’s a weird looking little thing, but it works; and that may be the final criterion of beauty.

There is nothing like an open camp fire to “make” a camp. Unfortunately, it has several drawbacks. Many areas frown on open burning as a fire hazard. It can, at times, convert a strained welcome into no welcome at all.

Unless you’re one of those natural woodsmen who can build a fire by rubbing two boy scouts together, a supply of dry wood is a necessity—a necessity that isn’t always available.

Because you are, by necessity, carrying a supply of gasoline in your cycle’s tank, a gasoline stove is a natural choice. There are two basic kinds of gasoline stoves: those that have to be pumped up and those that generate their own pressure.

The pump-up type seems to produce more heat, but it has a number of drawbacks that restrict its use by motorcyclists. They are designed to operate only on “white” gasoline—leaded gasolines tend to form deposits that block the burner—and they tend to be a bit more bulky than the self-generating type.

While weight isn’t as much of a consideration with the motorcyclist as it is with his backpacking counterpart, the limited storage space demands the most compact equipment available.

The self-generating stove can use almost any grade of gasoline. Its internal pressure is generated by using the heat from the burning fuel to vaporize part of the contents of the fuel tank. To start off this process, it is necessary to prime the burner with a teaspoon of gasoline.

An additional advantage is that this type of stove often comes with a set of cooking pans which nest one inside the other with the stove inside the kit. This results in quite a space saving. It is a good idea to drain all the gasoline out of the stove before putting it back into the kit—unless you like the taste of gasoline in your next meal.

The hairy chest school of outdoor life tends to look upon air mattresses as being something that indicates a decadent pleasure-lover—well, I’m a decadent pleasure-lover.

There are two attitudes concerning the amount one should spend when buying an air mattress. One school argues that you should buy the cheapest available and throw it out when the trip is over. They rarely mention that rainy night when the cheapy went flat before the trip was over, and they had to try to patch it with their “Cycle Spare,” getting gunk all over the inside of the tent.

The opposite attitude is the guy who goes out and spends ten or fifteen bucks, then steps on the blasted thing in the closet with his golf shoes on.

Some hedonistic types avoid the air mattress question by buying a sleeping pad made of sponge rubber. These are about four inches thick, but the whole thing will roll into a stuff bag only about 8 in. in diameter. They’re light, but a bit bulky. At least there’s no record of one ever going flat in the middle of the night.

Sleeping bags come in all price ranges and generally as the price goes up so does the quality. There are three types of sleeping bag: the mummy, the modified mummy, and the rectangular type.

The mummy resembles just what its name implies. It is a form-fitting bagwide at the shoulders and tapering down to fit snug around the feet. It has a head hole with a draw string so that it fits tight about the head. If you suffer from claustrophobia, skip the mummy bag.

The modified mummy is a bit looser and doesn’t taper strongly at the bottom.

The rectangular bag is just that. It has no head hole—the entire top of the bag is open—and there is no taper whatsoever. It strongly resembles a quilt that is folded over and has a zipper on two sides. Two of these bags can be fastened together to make a roomier unit.

Both natural and artificial materials are used for insulation in sleeping bags. Goose down is the most effective insulation known. It retains the maximum amount of body heat while allowing the body’s moisture to escape. Additionally, it will compress into a surprisingly small stuff bag for carrying. It is, however, expensive. A good quality goose down bag will cost in the neighborhood of a hundred dollars.

Polyester (artificial fabric) bags are much cheaper, but are noticeably heavier and more bulky.

It is wise to view the suggested minimum temperatures at which these bags are supposed to be comfortable with the same healthy skepticism which one reserves for the maximum speeds given for motorcycles.

As cycle companies seem to have a 40-lb. midget who rides the bike down an elevator shaft past the timer, so do the sleeping bag companies have an eskimo with ice water blood to test the sleeping bags. Add about 15 degrees, at least.

When setting up a camp, avoid gullies, since a rainstorm many miles away can suddenly convert them into a riverbed with you at the bottom.

An equally bad location for your tent is on the trail itself—you may find yourself being used for traction by some early-bird rider the next morning.

Pick an almost level spot (so rain will run off), away from overhanging branches. Ideally, it should have a supply of water somewhere near. Pitch the tent so that you can sleep with your head pointed up the slope.

Most campers are relatively honest people. But as a little added insurance, I run a black string around the camp and tie it to a tin can with a few pebbles in it. It is a sad comment on the American way of life that I sometimes find it easier to find an empty can than the pebbles.

Above all, always let someone know approximately where you plan to camp. A twisted ankle isn’t very serious, but a lQ-mile walk back to civilization with one is. m