REPORT FROM ITALY

CARLO PERELLI

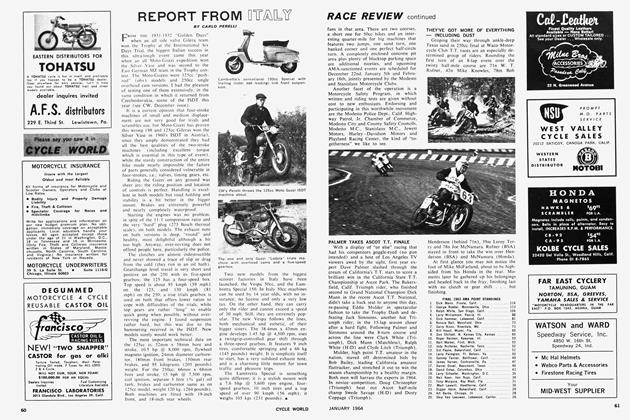

FINDLAY AND FONTANA

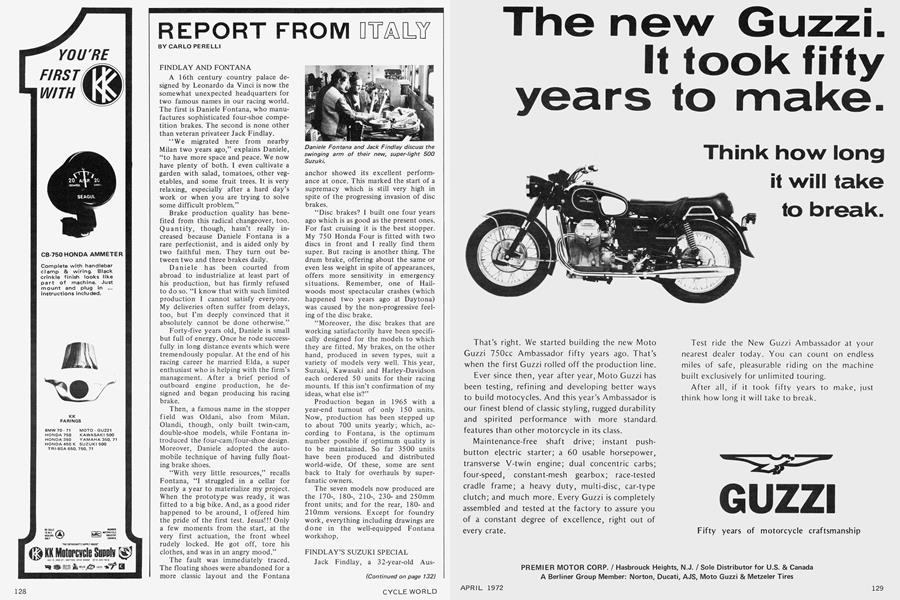

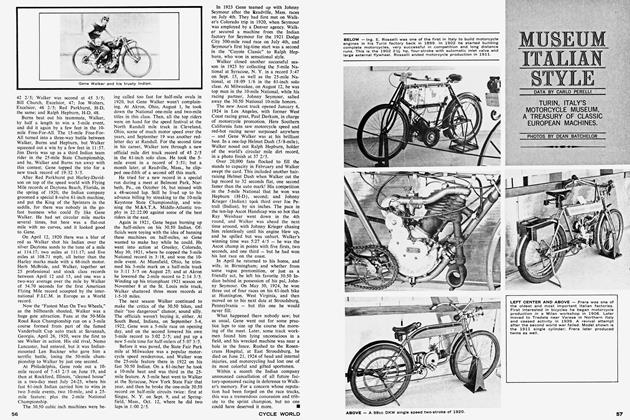

A 16th century country palace designed by Leonardo da Vinci is now the somewhat unexpected headquarters for two famous names in our racing world. The first is Daniele Fontana, who manufactures sophisticated four-shoe competition brakes. The second is none other than veteran privateer Jack Findlay.

“We migrated here from nearby Milan two years ago,” explains Daniele, “to have more space and peace. We now have plenty of both. I even cultivate a garden with salad, tomatoes, other vegetables, and some fruit trees. It is very relaxing, especially after a hard day’s work or when you are trying to solve some difficult problem.”

Brake production quality has benefited from this radical changeover, too. Quantity, though, hasn’t really increased because Daniele Fontana is a rare perfectionist, and is aided only by two faithful men. They turn out between two and three brakes daily.

Daniele has been courted from abroad to industrialize at least part of his production, but has firmly refused to do so. “I know that with such limited production I cannot satisfy everyone. My deliveries often suffer from delays, too, but I’m deeply convinced that it absolutely cannot be done otherwise.”

Forty-five years old, Daniele is small but full of energy. Once he rode successfully in long distance events which were tremendously popular. At the end of his racing career he married Elda, a super enthusiast who is helping with the firm’s management. After a brief period of outboard engine production, he designed and began producing his racing brake.

Then, a famous name in the stopper field was Oldani, also from Milan. Olandi, though, only built twin-cam, double-shoe models, while Fontana introduced the four-cam/four-shoe design. Moreover, Daniele adopted the automobile technique of having fully floating brake shoes.

“With very little resources,” recalls Fontana, “I struggled in a cellar for nearly a year to materialize my project. When the prototype was ready, it was fitted to a big bike. And, as a good rider happened to be around, I offered him the pride of the first test. Jesus!!! Only a few moments from the start, at the very first actuation, the front wheel rudely locked. He got off, tore his clothes, and was in an angry mood.”

The fault was immediately traced. The floating shoes were abandoned for a more classic layout and the Fontana anchor showed its excellent performance at once. This marked the start of a supremacy which is still very high in spite of the progressing invasion of disc brakes.

“Disc brakes? I built one four years ago which is as good as the present ones. For fast cruising it is the best stopper. My 750 Honda Four is fitted with two discs in front and I really find them super. But racing is another thing. The drum brake, offering about the same or even less weight in spite of appearances, offers more sensitivity in emergency situations. Remember, one of Hailwoods most spectacular crashes (which happened two years ago at Daytona) was caused by the non-progressive feeling of the disc brake.

“Moreover, the disc brakes that are working satisfactorily have been specifically designed for the models to which they are fitted. My brakes, on the other hand, produced in seven types, suit a variety of models very well. This year, Suzuki, Kawasaki and Harley-Davidson each ordered 50 units for their racing mounts. If this isn’t confirmation of my ideas, what else is?”

Production began in 1965 with a year-end turnout of only 150 units. Now, production has been stepped up to about 700 units yearly; which, according to Fontana, is the optimum number possible if optimum quality is to be maintained. So far 3500 units have been produced and distributed world-wide. Of these, some are sent back to Italy for overhauls by superfanatic owners.

The seven models now produced are the 170-, 180-, 210-, 230and 250mm front units; and for the rear, 180and 210mm versions. Except for foundry work, everything including drawings are done in the well-equipped Fontana workshop.

FINDLAY’S SUZUKI SPECIAL

Jack Findlay, a 32-year-old Australian, is quiet, valiant, and unassuming. He first came to ride in Europe in 1960, emerged as one of the best, but strangely never got a works ride. The only two people who have helped him in racing are Daniele Fontana in Italy and Harry Hunt in the U.S.

(Continued on page 132)

Continued from page 128

Findlay participates in about 60 European races yearly from March to October. Multiply that times 11 years of racing and you’ve got a lot of competition. In spite of an increasingly hard life for privateers, Jack holds a record of some 35 wins, among them the 500 class at the 1971 Ulster GP. Let’s also recall his 2nd place in the 1968 500cc world championship.

He has straddled practically every “over the counter” mount available in the last decade. He rates the 250 Bultaco TSS of 1966 as the best because it was both fast and reliable. His worst ride was on the 1969 Linto 500, which showed excellent potential but suffered various mechanical ills.

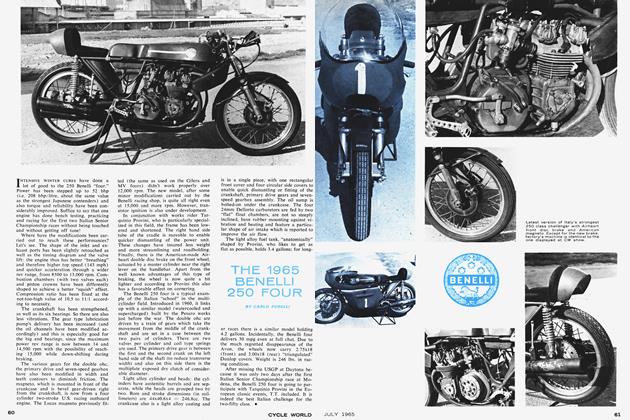

During the quiet winter months, Findlay and Fontana have been particularly busy setting up an ultra-light “special” powered by a 500 Suzuki Twin. Frame design follows the famous Matchless-Mclntyre concept which Findlay believes is the best roadholder. What’s more, its characteristics are particularly suited to Findlay’s riding style.

The engine has been prepared in two versions; one with air and one with water cooling. These will be alternated according to rules and situations. “Although I don’t think I have given them any bad publicity,” reports Jack with some sorrow, “I can’t get special racing parts from either the Suzuki factory or dealers. I must thank Daniele Fontana for much of the preparation—especially the complicated parts such as cylinders, heads, pistons, rings, gearboxes, etc.”

But why stick with the Suzuki Twin, modifying it into a racing powerplant when there are other good racing engines like the 500 Kawasaki available? The reasons are many. The Suzuki is less complicated, has a stronger crankcase and crankshaft, and gets considerably better gas mileage. In a World Championship event run over 125 miles, the Suzuki burns 6 to 6.5 gal. of fuel, while the Kawasaki needs 8.5 or 9 gal. The extra fueling stop necessary for the Kawasaki costs many positions.

So, with about the same power as the works mounts (a target not extremely difficult to reach) Findlay and Fontana are trying to challenge their rivals with lightness. Surely, their new mount will set a standard in the privateer field.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue