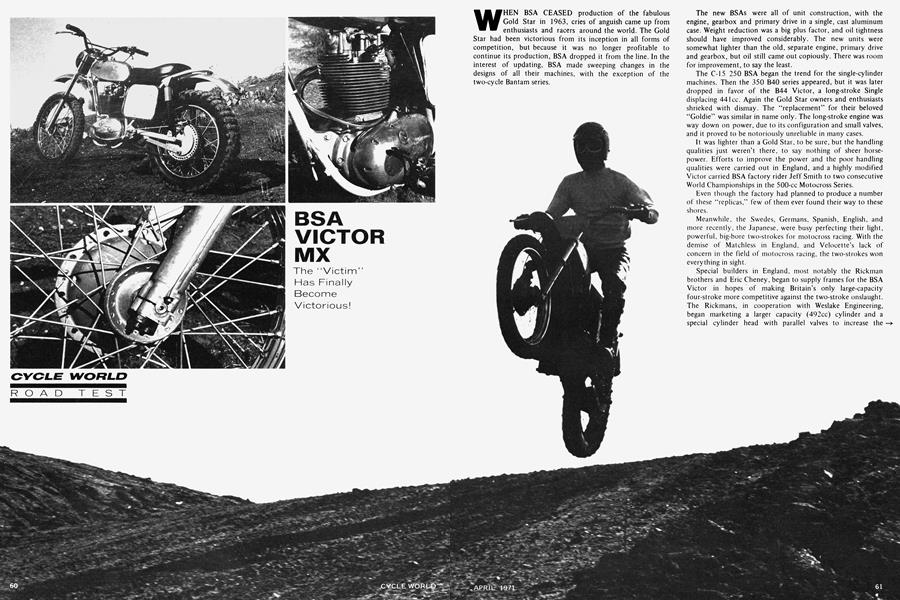

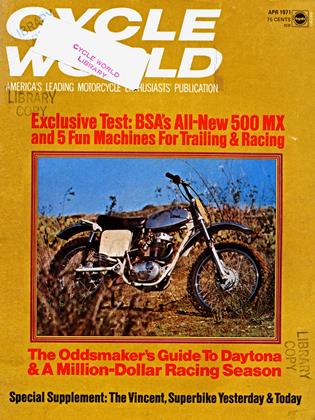

BSA VICTOR MX

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

The "Victim" Has Finally Become Victorious!

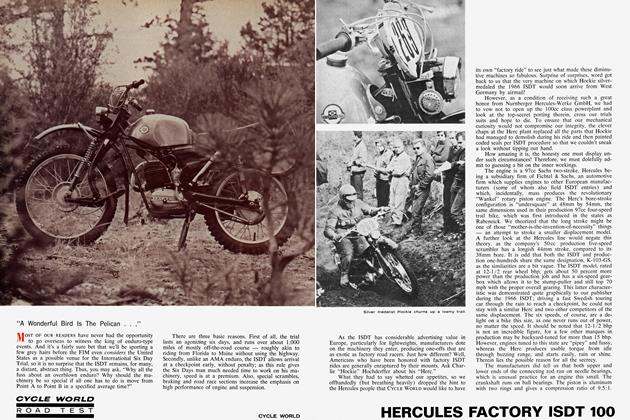

WHEN BSA CEASED production of the fabulous Gold Star in 1963, cries of anguish came up from enthusiasts and racers around the world. The Gold Star had been victorious from its inception in all forms of competition, but because it was no longer profitable to continue its production, BSA dropped it from the line. In the interest of updating, BSA made sweeping changes in the designs of all their machines, with the exception of the two-cycle Bantam series.

The new BSAs were all of unit construction, with the engine, gearbox and primary drive in a single, cast aluminum case. Weight reduction was a big plus factor, and oil tightness should have improved considerably. The new units were somewhat lighter than the old, separate engine, primary drive and gearbox, but oil still came out copiously. There was room for improvement, to say the least.

The C-15 250 BSA began the trend for the single-cylinder machines. Then the 350 B40 series appeared, but it was later dropped in favor of the B44 Victor, a long-stroke Single displacing 441cc. Again the Gold Star owners and enthusiasts shrieked with dismay. The “replacement” for their beloved “Goldie” was similar in name only. The long-stroke engine was way down on power, due to its configuration and small valves, and it proved to be notoriously unreliable in many cases.

It was lighter than a Gold Star, to be sure, but the handling qualities just weren’t there, to say nothing of sheer horsepower. Efforts to improve the power and the poor handling qualities were carried out in England, and a highly modified Victor carried BSA factory rider Jeff Smith to two consecutive World Championships in the 500-cc Motocross Series.

Even though the factory had planned to produce a number of these “replicas,” few of them ever found their way to these shores.

Meanwhile, the Swedes, Germans, Spanish, English, and more recently, the Japanese, were busy perfecting their light, powerful, big-bore two-strokes for motocross racing. With the demise of Matchless in England, and Velocette’s lack of concern in the field of motocross racing, the two-strokes won everything in sight.

Special builders in England, most notably the Rickman brothers and Eric Cheney, began to supply frames for the BSA Victor in hopes of making Britain’s only large-capacity four-stroke more competitive against the two-stroke onslaught. The Rickmans, in cooperation with Weslake Engineering, began marketing a larger capacity (492cc) cylinder and a special cylinder head with parallel valves to increase the machine’s performance. But none of these stopgap measures were really successful, and BSA saw the handwriting on the wall. The end result, for four-stroke enthusiasts, is quite probably the best thing since sliced bread.

Practically the only item the new (B50) Victor shares with its predecessor (B44) is the crankcase, and even that has been redesigned to accommodate another main bearing on the drive side. Gearbox and clutch components are also the same, but the power-producing portion is all new.

Now a full 500 (actual displacement is 499cc). the Victor sports an 84-mm bore. The new cylinder head can now breathe and uses a 1.755-in. inlet valve and a 1.531-in. exhaust valve, as opposed to the B44's 1.540-in. inlet valve and 1.412-in. exhaust valve. A larger 32-mm Amal Concentric carburetor handles the engine’s thirst for fuel and air. and having a float at the bottom precludes flooding when leaning the machine over. Our test machine carbureted beautifully right from an idle, and showed no signs of a Hat spot anywhere in the engine’s rev range.

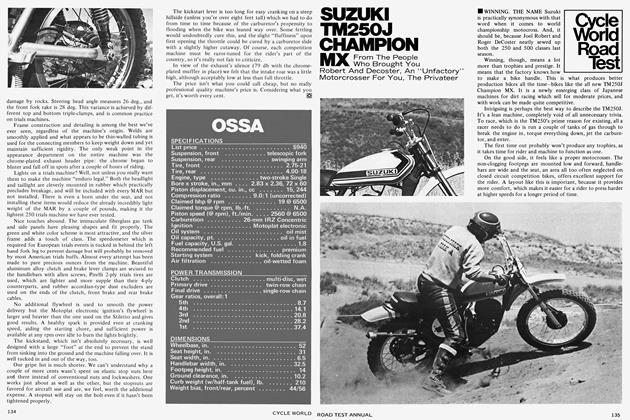

Even though the Victor MX is slightly down in peak horsepower from some of the more potent two-strokes currently available, it makes up the deficiency with a tremendously broad power band. Running on C.R. Axtell's dynamometer, our test machine was choked down to 3400 rpm, a relatively low speed at which it was pulling strongly. Yet. it still produces good power at 6700 rpm, well over its maximum horsepower engine speed of 6200 rpm.

Also, the way in which the power comes on is reassuring to less experienced riders. A four-stroke fires only half as often as a two-stroke, which helps the rear wheel get a better bite in slippery going. It’s also less abrupt when “coming onto the pipe.” The bike feels like a tractor in low, and buzzes nearly as high as the old Gold Star. It still doesn't put out quite as much power as a good Gold Star, but the combination is somewhat easier to live with.

Our test machine was used in the Trans-AMA series by Chuck “Feets” Minert, a man who has been riding BSA in competition longer than any other single person. “Feets” had made some slight modifications to the machine to suit his large frame and weight, but aside from the handlebars, slightly shortened footpegs, a crankcase breather coming out of the top of the clutch cover, and an odd aluminum nut and bolt here and there, the machine was perfectly standard. It's interesting to note that the six Victor MX machines that ran the entire Trans-AMA series had only one failure at one race, and that was a faulty ignition coil!

Transmission and clutch components were used, abused, slipped and thrashed without a sign of protest. Practically no oil wept past the gaskets. We would like to see the substitution of the older, closer first gear for the current one. as it's just too low with the standard gearing. But shifting is light and crisp, and the clutch went through the entire day without needing adjustment. A series of rubber blocks inside the clutch hub serves to cushion the engine's power impulses and reduce consequent wear of the gearbox components and the chains.

The Lucas Energy Transfer (capacitor-type) ignition system gets our plaudits this time. Early Lucas FT systems frightened the average owner and mechanic because they were not very well understood, and some of the components were of less than satisfactory quality. This led to failures.

Actually, an FT system is nothing more than an AC magneto with the ignition points and secondary coil separated from the alternator itself. Benefits from separating these items are less heat, easier maintenance and somewhat better insulation. But, there are also more wires to shake loose or break, and the early stators (mounted in the primary chaincase with the clutch and primary chain) often had faulty insulation and were prone to shorts.

In order to function correctly, the E-gap (also called the “phase”) of the alternator must be set correctly by moving the stator around the rotor’s magnets to agree exactly with the opening of the contact breaker for a good, hot spark. Earlier systems were difficult to set, and often slipped a little out of phase.

Thankfully, Lucas has come up with what looks like a 100-percent reliable system. Even though the Victor MX is hampered by an ultra-slow cranking ratio, which makes it difficult to spin the engine very fast with the kickstarter, a good, fat spark was provided by the ignition system.

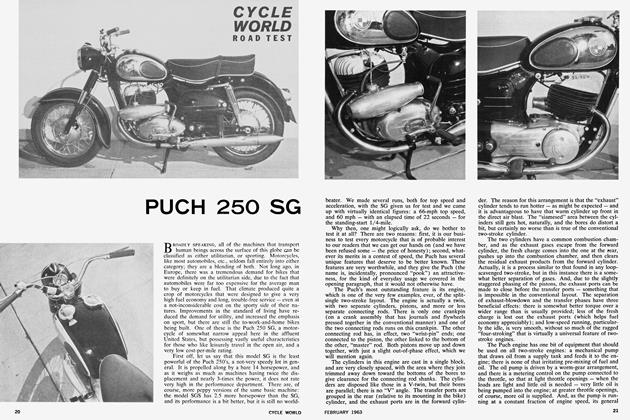

A great deal of credit for the Victor MX’s success must go to the frame design, and of course to the front forks. Following the Rickman Metisse practice of putting the frame tubes to work as an oil reservoir, BSA has been able to pare off a few pounds by doing away with the separate oil tank. Frame geometry has been copied from John Banks' highly successful Victor motocross mount, and all the frames feature tapered roller bearings in the steering head for less fore-and-aft fork movement and more precise steering.

The swinging arm pivot is mounted eccentrically. Rear chain tension is adjusted in steps by means of relocating the swinging arm’s position exactly the same amount on both sides. This is accomplished by using plates with locating holes with no in-between settings. Hence, it’s impossible to get the rear wheel out of line.

Frame construction is excellent, with smooth welds and deftly applied paint work. The only thing we felt the frame was missing was a bash plate to protect the underside of the engine from rocks, but one could easily be fabricated out of aluminum.

The front forks deserve special mention because of their superb action and robust construction. They follow Ceriani practice in that they have internal springs, are hydraulically dampened in both directions, and have rubber wipers to keep dirt and moisture from entering and damaging the oil seals. The entire assembly, including the massive cast-aluminum legs and fork yokes, is manufactured by BSA. A full 6 3/4 in. of travel is claimed, and the fork spring rate seemed proper for a 1 60-lb. rider.

The fork seals on our test bike wceped oil. but the bike already had several races behind it. Four 5/16-in. studs on each leg secure the bottom axle clamp rigidly in place and obviate the need for a fork brace to keep the wheel pointed exactly where the rider wants it.

New cast aluminum brake hubs help reduce unsprung weight and allow the wheels to follow surface irregularities more closely. Both brakes operated smoothly and were deemed perfect for a machine of the MX’s weight. The rear hub is conical in shape and incorporates the brake drum. Quick-change rear sprockets are featured, making the alteration of the f inal drive ratio a snap.

With all the work put into the large backbone frame and the extensive use of aluminum alloys, the Victor’s weight has been pruned to just a shade under 260 lb., wet. Even before the two-stroke motocross machines began to develop their present power, they always had a distinct weight advantage over a four-stroke of similar size. Now that advantage has been narrowed and the Victor MX weighs just a few pounds more than the Husky 405, the Maico and the CZ, and just slightly less than the Bultaco motocross machine. Right in the old ballpark, and the riding ease of the Victor makes it more than just a passing threat. Four-stroke fans unite, here's your machine!

BSA VICTOR MX

$1183

View Full Issue

View Full Issue