MONTESA KING SCORPION

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

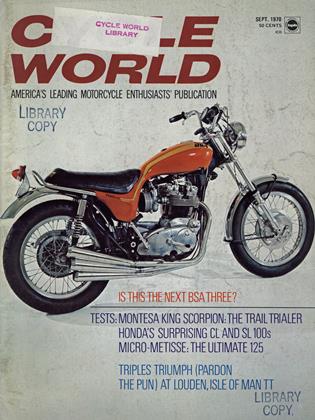

It Leaps Logs At A Single Tweak, Is Faster Than A Speeding Cota, Softer On The Posterior, But Still Feels Like A Trialer. It's A Trail-Trialer.

MONTESA HAS BEEN sorely late in providing its followers with a true combination street/trail machine.

The old Scorpion was basically a street bike, which showed up street bike deficiencies when applied to earnest trailing use.

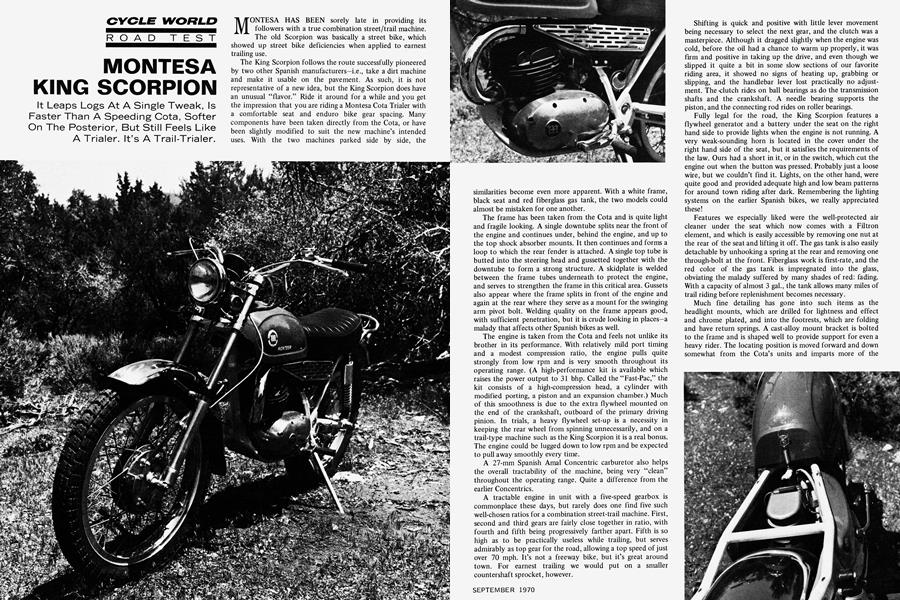

The King Scorpion follows the route successfully pioneered by two other Spanish manufacturers—i.e., take a dirt machine and make it usable on the pavement. As such, it is not representative of a new idea, but the King Scorpion does have an unusual “flavor.” Ride it around for a while and you get the impression that you are riding a Montesa Cota Trialer with a comfortable seat and enduro bike gear spacing. Many components have been taken directly from the Cota, or have been slightly modified to suit the new machine’s intended uses. With the two machines parked side by side, the similarities become even more apparent. With a white frame, black seat and red fiberglass gas tank, the two models could almost be mistaken for one another.

The frame has been taken from the Cota and is quite light and fragile looking. A single downtube splits near the front of the engine and continues under, behind the engine, and up to the top shock absorber mounts. It then continues and forms a loop to which the rear fender is attached. A single top tube is butted into the steering head and gussetted together with the downtube to form a strong structure. A skidplate is welded between the frame tubes underneath to protect the engine, and serves to strengthen the frame in this critical area. Gussets also appear where the frame splits in front of the engine and again at the rear where they serve as a mount for the swinging arm pivot bolt. Welding quality on the frame appears good, with sufficient penetration, but it is crude looking in places—a malady that affects other Spanish bikes as well.

The engine is taken from the Cota and feels not unlike its brother in its performance. With relatively mild port timing and a modest compression ratio, the engine pulls quite strongly from low rpm and is very smooth throughout its operating range. (A high-performance kit is available which raises the power output to 31 bhp. Called the “Fast-Pac,” the kit consists of a high-compression head, a cylinder with modified porting, a piston and an expansion chamber.) Much of this smoothness is due to the extra flywheel mounted on the end of the crankshaft, outboard of the primary driving pinion. In trials, a heavy flywheel set-up is a necessity in keeping the rear wheel from spinning unnecessarily, and on a trail-type machine such as the King Scorpion it is a real bonus. The engine could be lugged down to low rpm and be expected to pull away smoothly every time.

A 27-mm Spanish Amal Concentric carburetor also helps the overall tractability of the machine, being very “clean” throughout the operating range. Quite a difference from the earlier Concentrics.

A tractable engine in unit with a five-speed gearbox is commonplace these days, but rarely does one find five such well-chosen ratios for a combination street-trail machine. First, second and third gears are fairly close together in ratio, with fourth and fifth being progressively farther apart. Fifth is so high as to be practically useless while trailing, but serves admirably as top gear for the road, allowing a top speed of just over 70 mph. It’s not a freeway bike, but it’s great around town. For earnest trailing we would put on a smaller countershaft sprocket, however.

Shifting is quick and positive with little lever movement being necessary to select the next gear, and the clutch was a masterpiece. Although it dragged slightly when the engine was cold, before the oil had a chance to warm up properly, it was firm and positive in taking up the drive, and even though we slipped it quite a bit in some slow sections of our favorite riding area, it showed no signs of heating up, grabbing or slipping, and the handlebar lever lost practically no adjustment. The -clutch rides on ball bearings as do the transmission shafts and the crankshaft. A needle bearing supports the piston, and the connecting rod rides on roller bearings.

Fully legal for the road, the King Scorpion features a flywheel generator and a battery under the seat on the right hand side to provide lights when the engine is not running. A very weak-sounding horn is located in the cover under the right hand side of the seat, but it satisfies the requirements of the law. Ours had a short in it, or in the switch, which cut the engine out when the button was pressed. Probably just a loose wire, but we couldn’t find it. Lights, on the other hand, were quite good and provided adequate high and low beam patterns for around town riding after dark. Remembering the lighting systems on the earlier Spanish bikes, we really appreciated these!

Features we especially liked were the well-protected air cleaner under the seat which now comes with a Filtron element, and which is easily accessible by removing one nut at the rear of the seat and lifting it off. The gas tank is also easily detachable by unhooking a spring at the rear and removing one through-bolt at the front. Fiberglass work is first-rate, and the red color of the gas tank is impregnated into the glass, obviating the malady suffered by many shades of red: fading. With a capacity of almost 3 gal., the tank allows many miles of trail riding before replenishment becomes necessary.

Much fine detailing has gone into such items as the headlight mounts, which are drilled for lightness and effect and chrome plated, and into the footrests, which are folding and have return springs. A cast-alloy mount bracket is bolted to the frame and is shaped well to provide support for even a heavy rider. The locating position is moved forward and down somewhat from the Cota’s units and imparts more of the rider’s weight over the front end of the machine. This enhances steering and weight distribution for general trail riding, as it makes the front wheel more responsive to steering, rather than depending on body english to navigate.

Muffling is excellent and the entire exhaust system is tucked in and out of the way. There is no approved spark arrestor incorporated within the muffler, however, and the exhaust pipe tip’s unconventional shape would make it difficult to fit one of the commercially produced models.

The use of light alloy is welcomed in many places. Fenders, wheel rims and both the top and bottom triple clamps are of alloy, as are the fork tubes and wheel hubs. With an unladen weight of 274 lb., the Montesa is slightly heavier than most street/trail 250’s, but the weight is not a detriment.

Handhng is the Montesa’s forte. Wheelbase is almost 3 in. longer than the Cota’s, with the increase in length coming from the different triple clamps, the mounting point of the front axle (which is at the front of the fork legs), and from an increase in the length of the swinging arm. The front axle mounting position also serves to increase the trail slightly and slow down the steering somewhat. This, of course, is necessary for fast riding over rough country and is an improvement for street riding as well.

Suspension is quite soft and well damped, which helps keep both wheels on the ground. The front forks are of Montesa’s own design and manufacture and are some of the best we’ve ever tested. They were almost impossible to bottom in rough going, but were soft and sensitive enough to follow even the slightest undulations of the ground. It proved to be a superior fork in every respect. The rear shocks are also excellent and feature a five-position rear spring rate adjustment.

Riding out in the boonies became a real pleasure instead of a challenge. The front end is light enough to permit jumping large obstacles merely by giving the handlebars a rearward jerk and tweaking open the throttle in the lower gears. Low speed steering is light and predictable.

Our test bike was fitted with Firestone Super Sportsman tires which might well be the best all-around tire available. The lug pattern is similar to a trials tire, but the profile is rounded. So adequate traction is provided in the dirt (except for deep mud), yet street riders need not worry much about the tires slipping unduly while cornering and braking. A curious phenomenon showed up while ridirig above 50 mph on the street: there was a tendency for the front end to “search” which was a little disconcerting at first, but remained of such small magnitude that we soon became able to ignore it almost completely. It is probably attributable to a combination of the tires and steering geometry. The same tendency showed up at speed in the dirt, but was less noticeable there.

Another feature we liked was the incorporation of a rear chain oiler in the drive side of the swinging arm. Oil is delivered to the rear chain through an adjustable needle valve, and the filler is located at the forward end of the swinging arm shaft.

Our objections to the machine are few, the main one being the front brake which is much too sensitive for dirt work, although very good for the road. It is a double leading shoe affair which looks as though it came from the Impala Sport we tested a couple of years ago, and it still retains the air scoop which is blocked off by a plastic grille. We would much prefer to see a smaller, less fierce brake on the front, but the rear unit was excellent.

In retrospect, the Montesa King Scorpion is all it’s cracked up to be, and then some. A well-finished, good handling “trailer-trialer” that would be a worthy addition to anyone’s stable. M

MONTESA

KING SCORPION

$848

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

September 1970 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1970 -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

September 1970 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

September 1970 -

Special Feature

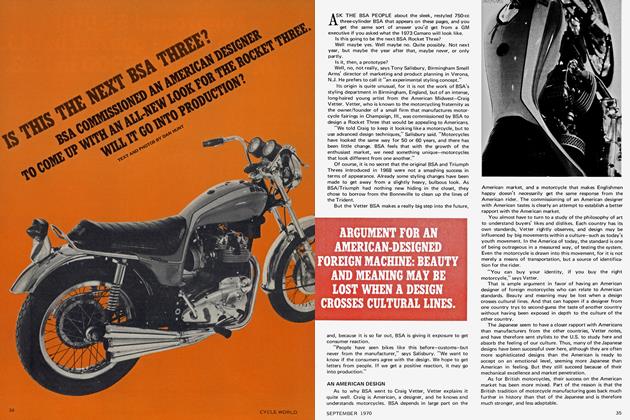

Special FeatureIs This the Next Bsa Three?

September 1970 By Dan Hunt -

Features

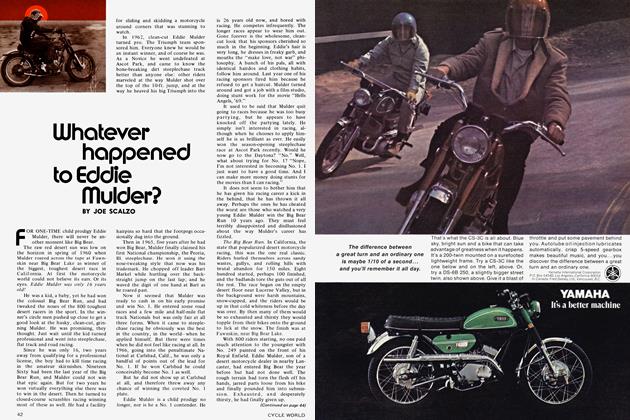

FeaturesWhatever Happened To Eddie Mulder?

September 1970 By Joe Scalzo