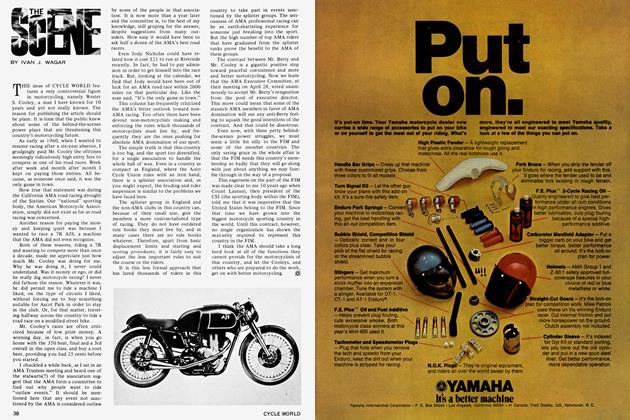

REPORT FROM JAPAN

YUKIO KURODA

CW VISITS YAMAHA COURSE

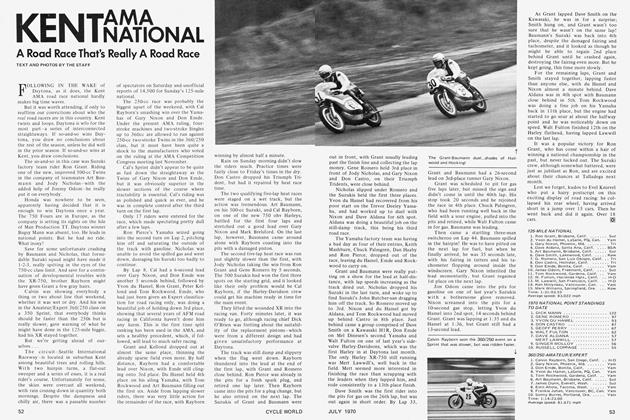

The occasion was the road test of the new Yamaha 650 by CYCLE WORLD’S counterpart in Japan, Motorcyclist. The staff asked us to go along with them to ride the big Yamaha and give our impressions of this first four-stroke roadster from Nippon Gakki (the name of Yamaha’s parent firm). It was quite a while after the machine had first been announced, so to make the test more interesting we were all invited to try the machine out at the lovely new private track which Yamaha has built to test new machines (and which Toyota, a frequent collaborator of Yamaha on projects like the beautiful 2000GT, also uses). The track is appropriately named Yamaha Course, and its design strongly resembles that of Suzuka Circuit, with one long straight, a collapsing radius bend (called “the spoon”), quick S bends in succession, and a number of rising and descending sections which gain and lose camber as they pass over low hills.

The six-kilometer course was only recently completed, and still has the smooth, clean, high-grip surface which road racers know and love so well.

The 650 wasn’t really the best machine to play earholer on, but I did have a lot of fun without scaring myself on the twisty course—being careful not to push things too hard, as there have already been a number of accidents on the complex bends; they are challenging to a smooth and careful rider, but too much foolhardiness or a clumsy-handling machine will flip you off on your can faster than you can say “Where did my Yamaha 650 go?”

And what else should we see at the Yamaha Course, or at least get a tiny peek at before they roared out of sight, than some new Twins that sounded like 125s. What have we here? I shall have to do a little Houdini and see what this new mount from Yamaha is; and I promise you’ll hear soon thereafter.

RECORD ’69 SALES FIGURES

The Japanese motorcycle industry set a production record of 2,447,391 in 1966—and many doubted if they’d ever manage to equal it again. Well, they did.

In 1969 a new record of 2,576,873 motorcycles rolled off the lines, Honda ahead as always. The biggest maker tooled out 1,534,882 two-wheel machines, and they hope to go for two million this year. About half of their production went into exports, and Honda hopes to increase exports to a million machines this year; this would be a 43 percent increase over 1969.

Yamaha has a firm hold on second place, having gone over the half million mark for the first time in 1969. They’ve had trouble filling orders from home and abroad (especially for off-road machines, like the wildly popular DT-1), but would like to push past the 650,000 mark this year, with 300,000 for export.

Suzuki was the only Japanese maker to fail to substantially increase motorcycle production in 1969: their production shows 398,784 machines versus 365,330 in 1968. The official reason given is the heavy demand for the 360-cc Fronte mini-car, a sweet piece of automotive talent to be sure, but I suspect that business troubles in the States and elsewhere played a role in their losing ground to others, especially Kawasaki. I’m convinced that Suzuki has the motorcycles to meet the competition, but keen machines are only one factor in a successful business, as any dealer will tell you. Suzuki’s making a full-bore attempt to claw back up in 1970, and I wish them well in their effort. Just get busy and build that mythical three-cylinder 650-cc machine that I put myself out on a limb telling the readers about, please. Or otherwise they’ll organize a lynch party, headed up by a group of vigilante dealers riding 500s they can’t sell and come all the way across the water to string me up for spreading false stories about future models.

Meanwhile back at the assembly line Kawasaki was busy ringing up a fantastic 31.1 percent growth rate in 1969, with a production of 102,406 machines. The main single reason is the elegant and swift-as-a-bullet Mach III 500, which helped them over the hundred thou mark after two rather slow years of 79,194 (1967) and 78,124 (1968).

This year they’d like to up production over the 150,000 mark, and their terrific position in the U.S. market should make them confident of such an increase.

Little Bridgestone keeps building fine motorcycles, but still hasn’t put enough effort in the selling end to make the competition hurt much; their 1969 total of 11,873 is sharply off from 17,659 in 1968.

The industry is becoming a little edgy about safety and emission control problems in the U.S. and Europe, but I believe their general optimism for future increases in sales is fully justified. And optimistic is what they are: the industry plans to build a total of 3.3 million motorcycles this year.

FOREIGN FACTORIES?

One way they hope to do it is with more production in new and modernized plants in Japan—but with a very tight labor situation, some makers are looking overseas to other countries for lots of land and low-priced labor to increase production. Yamaha and Suzuki already have assembly plants in Thailand, and Honda surprised a lot of people when they announced they were opening up an assembly plant in Belgium some years back.

Now they are looking over places like Mexico, Venezuela and Taiwan for fullfledged factories, to build bikes from the bottom up-savings in freight, import duty for domestic sales in the country of manufacture, and lower costs all around may someday make it possible for you to look on the engine of your V-8 Honda and see a plaque proudly proclaiming “Made in Mexico.”

AUTOMATIC TRANSMISSIONS?

Quite possibly, we may see automatic trannies on some future Hondas. One reason is the totally original automatic unit on the N360 and 1300 sedans, both of which have integral engine/transmission “motorcycle”-type drive components, with an ultra-compact torque converter matched to the engine, giving (Honda says) less power loss than a comparable manual gearbox and clutch arrangement. Acceleration doesn’t suffer noticeably, either, with the three-speed units.

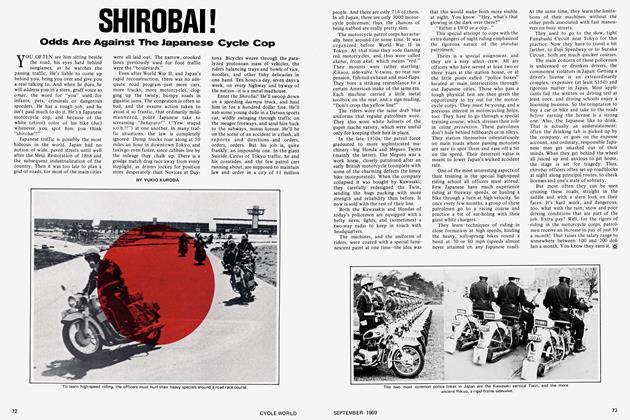

1 was walking through the gamy amusement area of Shinjuku one afternoon, and just after passing a startling sign advertising the delights of the “Club Lesbian” stopped at a crossing. Waiting for a green light was a police Honda CB750P, like the ones we showed you in a previous report. I don’t know why he attracted my attention, but I watched closely as the light changed to green, and I’ll be blessed and baptized if, without taking his hand from the grip or even looking at the clutch lever, he pushed the shift lever into first, motored off, and shifted into second, again without touching the clutch! Were my eyes deceiving me? I don’t think so. And the more 1 think about it, the more it seems that if Honda wanted to build an automatic clutch version of the big Four, it would make beautiful sense to let Tokyo police, who often have to creep along in slow traffic, where frequent clutching can be difficult and tiring, try out the prototype units.

Checking over a diagram of the CB750’s gearbox arrangement, it would seem that extensive modifications would have to be made to employ a unit similar to the foot clutch actuation of the Super Cub, in which a long extension of the spline d shift shaft travels over to the right side of the engine, where it hooks onto a throw-out mechanism on the clutch. The shaft on the 750 is stubby, and there is no provision for right-hand shifting either, you’ll recall.

The sound the bike made when the officer pushed the lever into first was a good healthy klunk that sounds just like mine and yours, so the best guess would be a semi-automatic arrangement, in which you would still use the foot lever, but could ignore the clutch. And if there’s anybody smart enough and daring enough to try such a trick, it is Honda.

The cherry blossoms unfurl across the countryside. Spring winds and spring rains come and go suddenly. The temperature begins its even climb to a pleasant level. Friends, it’s time to hit the road again.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue