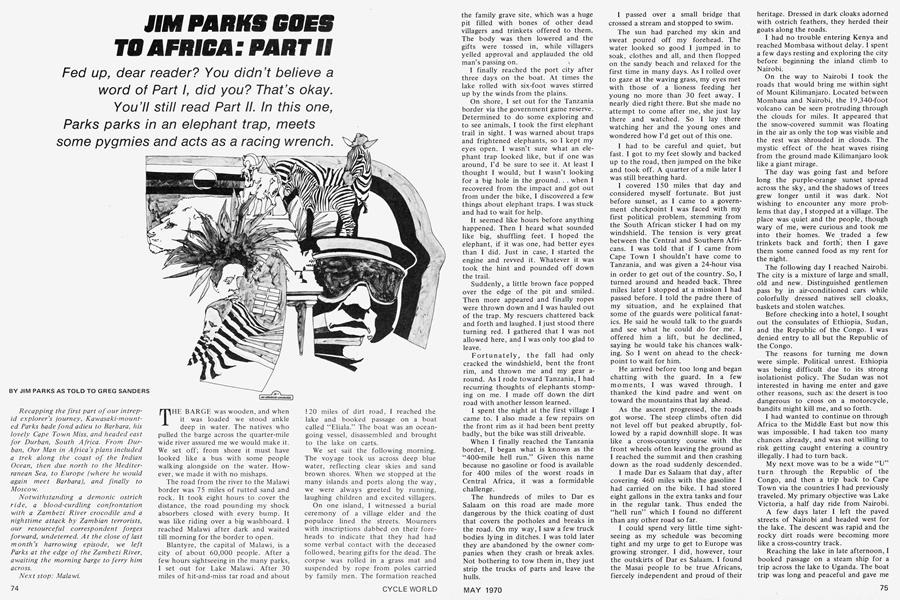

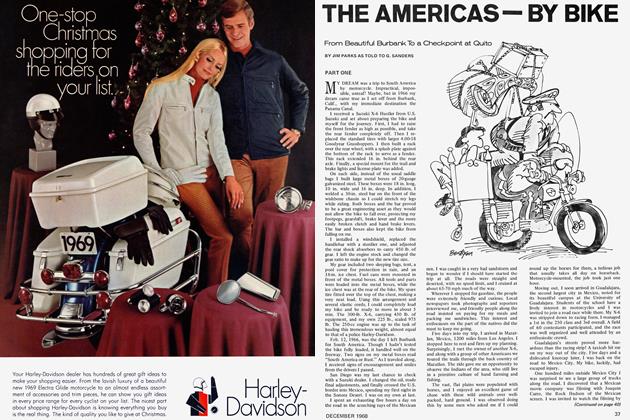

JIM PARKS GOES TO AFRICA: PART II

Fed up, dear reader? You didn’t believe a word of Part I, did you? That’s okay. You’ll still read Part II. In this one, Parks parks in an elephant trap, meets

JIM PARKS

GREG SANDERS

Recapping the first part of our intrepid explorer’s journey, Kawasaki-mounted Parks bade fond adieu to Barbara, his lovely Cape Town Miss, and headed east for Durban, South Africa. From Durban, Our Man in Africa’s plans included a trek along the coast of the Indian Ocean, then due north to the Mediterranean Sea, to Europe (where he would again meet Barbara), and finally to Moscow.

Notwithstanding a demonic ostrich ride, a blood-curdling confrontation with a Zambezi River crocodile and a nighttime attack by Zambian terrorists, our resourceful correspondent forges forward, undeterred. At the close of last month’s harrowing episode, we left Parks at the edge of the Zambezi River, awaiting the morning barge to ferry him across.

Next stop: Malawi.

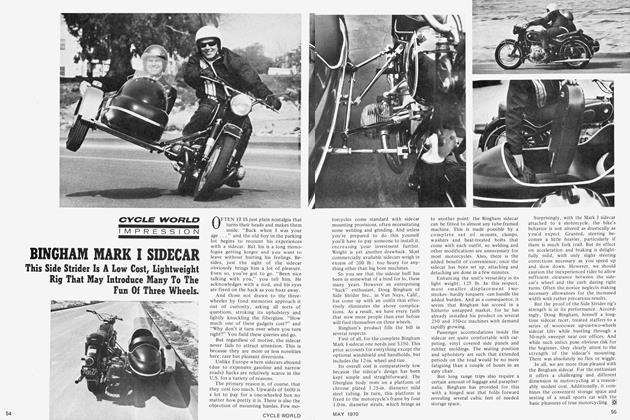

THE BARGE was wooden, and when it was loaded we stood ankle deep in water. The natives who pulled the barge across the quarter-mile wide river assured me we would make it. We set off; from shore it must have looked like a bus with some people walking alongside on the water. However, we made it with no mishaps.

The road from the river to the Malawi border was 75 miles of rutted sand and rock. It took eight hours to cover the distance, the road pounding my shock absorbers closed with every bump. It was like riding over a big washboard. I reached Malawi after dark and waited till morning for the border to open.

Blantyre, the capital of Malawi, is a city of about 60,000 people. After a few hours sightseeing in the many parks, I set out for Lake Malawi. After 30 miles of hit-and-miss tar road and about 120 miles of dirt road, I reached the lake and booked passage on a boat called "Eliala." The boat was an ocean going vessel, disassembled and brought to the lake on carts.

We set sail the following morning. The voyage took us across deep blue water, reflecting clear skies and sand brown shores. When we stopped at the many islands and ports along the way, we were always greeted by running, laughing children and excited villagers.

On one island, I witnessed a burial ceremony of a village elder and the populace lined the streets. Mourners with inscriptions dabbed on their foreheads to indicate that they had had some verbal contact with the deceased followed, bearing gifts for the dead. The corpse was rolled in a grass mat and suspended by rope from poles carried by family men. The formation reached the family grave site, which was a huge pit filled with bones of other dead villagers and trinkets offered to them. The body was then lowered and the gifts were tossed in, while villagers yelled approval and applauded the old man’s passing on. v

I finally reached the port city after three days on the boat. At times the lake rolled with six-foot waves stirred up by the winds from the plains.

On shore, I set out for the Tanzania border via the government game reserve. Determined to do some exploring and to see animals, I took the first elephant trail in sight. I was warned about traps and frightened elephants, so I kept my eyes open. I wasn’t sure what an elephant trap looked like, but if one was around, I’d be sure to see it. At least I thought I would, but I wasn’t looking for a big hole in the ground. . . when I recovered from the impact and got out from under the bike, I discovered a few things about elephant traps. I was stuck and had to wait for help.

It seemed like hours before anything happened. Then I heard what sounded like big, shuffling feet. I hoped the elephant, if it was one, had better eyes than I did. Just in case, I started the engine and revved it. Whatever it was took the hint and pounded off down the trail.

Suddenly, a little brown face popped over the edge of the pit and smiled. Then more appeared and finally ropes were thrown down and I was hauled out of the trap. My rescuers chattered back and forth and laughed. I just stood there turning red. I gathered that I was not allowed here, and I was only too glad to leave.

Fortunately, the fall had only cracked the windshield, bent the front rim, and thrown me and my gear around. As I rode toward Tanzania, I had recurring thoughts of elephants stomping on me. I made off down the dirt road with another lesson learned.

I spent the night at the first village I came to. I also made a few repairs on the front rim as it had been bent pretty badly, but the bike was still driveable.

When I finally reached the Tanzania border, I began what is known as the “400-mile hell run.” Given this name because no gasoline or food is available for 400 miles of the worst roads in Central Africa, it was a formidable challenge.

The hundreds of miles to Dar es Salaam on this road are made more dangerous by the thick coating of dust that covers the potholes and breaks in the road. On my way, I saw a few truck bodies lying in ditches. I was told later they are abandoned by the owner companies when they crash or break axles. Not bothering to tow them in, they just strip the trucks of parts and leave the hulls.

I passed over a small bridge that crossed a stream and stopped to swim.

The sun had parched my skin and sweat poured off my forehead. The water looked so good I jumped in to soak, clothes and all, and then flopped on the sandy beach and relaxed for the first time in many days. As I rolled over to gaze at the waving grass, my eyes met with those of a lioness feeding her young no more than 30 feet away. I nearly died right there. But she made no attempt to come after me, she just lay there and watched. So I lay there watching her and the young ones and wondered how I’d get out of this one.

I had to be careful and quiet, but fast. I got to my feet slowly and backed up to the road, then jumped on the bike and took off. A quarter of a mile later I was still breathing hard.

I covered 150 miles that day and considered myself fortunate. But just before sunset, as I came to a government checkpoint I was faced with my first political problem, stemming from the South African sticker I had on my windshield. The tension is very great between the Central and Southern Africans. I was told that if I came from Cape Town I shouldn’t have come to Tanzania, and was given a 24-hour visa in order to get out of the country. So, I turned around and headed back. Three miles later I stopped at a mission I had passed before. I told the padre there of my situation, and he explained that some of the guards were political fanatics. He said he would talk to the guards and see what he could do for me. I offered him a lift, but he declined, saying he would take his chances walking. So I went on ahead to the checkpoint to wait for him.

He arrived before too long and began chatting with the guard. In a few moments, I was waved through. I thanked the kind padre and went on toward the mountains that lay ahead.

As the ascent progressed, the roads got worse. The steep climbs often did not level off but peaked abruptly, followed by a rapid downhill slope. It was like a cross-country course with the front wheels often leaving the ground as I reached the summit and then crashing down as the road suddenly descended.

I made Dar es Salaam that day, after covering 460 miles with the gasoline I had carried on the bike. I had stored eight gallons in the extra tanks and four in the regular tank. Thus ended the “hell run” which I found no different than any other road so far.

I could spend very little time sightseeing as my schedule was becoming tight and my urge to get to Europe was growing stronger. I did, however, tour the outskirts of Dar es Salaam. I found the Masai people to be true Africans, fiercely independent and proud of their heritage. Dressed in dark cloaks adorned with ostrich feathers, they herded their goats along the roads.

I had no trouble entering Kenya and reached Mombasa without delay. I spent a few days resting and exploring the city before beginning the inland climb to Nairobi.

On the way to Nairobi I took the roads that would bring me within sight of Mount Kilimanjaro. Located between Mombasa and Nairobi, the 19,340-foot volcano can be seen protruding through the clouds for miles. It appeared that the snow-covered summit was floating in the air as only the top was visible and the rest was shrouded in clouds. The mystic effect of the heat waves rising from the ground made Kilimanjaro look like a giant mirage.

The day was going fast and before long the purple-orange sunset spread across the sky, and the shadows of trees grew longer until it was dark. Not wishing to encounter any more problems that day, I stopped at a village. The place was quiet and the people, though wary of me, were curious and took me into their homes. We traded a few trinkets back and forth; then I gave them some canned food as my rent for the night.

The following day I reached Nairobi. The city is a mixture of large and small, old and new. Distinguished gentlemen pass by in air-conditioned cars while colorfully dressed natives sell cloaks, baskets and stolen watches.

Before checking into a hotel, I sought out the consulates of Ethiopia, Sudan, and the Republic of the Congo. I was denied entry to all but the Republic of the Congo.

The reasons for turning me down were simple. Political unrest. Ethiopia was being difficult due to its strong isolationist policy. The Sudan was not interested in having me enter and gave other reasons, such as: the desert is too dangerous to cross on a motorcycle, bandits might kill me, and so forth.

I had wanted to continue on through Africa to the Middle East but now this was impossible. I had taken too many chances already, and was not willing to risk getting caught entering a country illegally. I had to turn back.

My next move was to be a wide “Lí” turn through the Republic of the Congo, and then a trip back to Cape Town via the countries I had previously traveled. My primary objective was Lake Victoria, a half day ride from Nairobi.

A few days later I left the paved streets of Nairobi and headed west for the lake. The descent was rapid and the rocky dirt roads were becoming more like a cross-country track.

Reaching the lake in late afternoon, I booked passage on a steam ship for a trip across the lake to Uganda. The boat trip was long and peaceful and gave me a chance to think. The first thing that came to mind was my agreement to meet Barbara in Spain. That seemed a long way off and was made more distant by the fact that I was heading the opposite direction. So I turned my mind to other thoughts. I had read about the Pygmies who live in the region I was to visit and decided I should try to see the little people.

Continued from page 75

We landed near Kanyrola, Uganda, and I immediately set out toward Stanleyville in search of Pygmies. The area was rather mountainous and night traveling was foolhardy, so I stopped and pitched a tent for the night. It was cold and silent and I huddled near the fire. Now and then something would move in the bushes and scare me half to death. There were few things visible in the solid black that enclosed me. Once a shadow darted across the road and silently disappeared. I thought about Pygmies and how they were supposed to be head hunters. I zipped my sleeping bag all the way to the top and slept.

Next morning, I traveled in the direction of Stanleyville so as to be near petrol stations and on a main road. On the way, I occasionally took off through the bushes searching for a village of little people, but to no avail. But I did discover that the trails left by animals were always well packed and smooth. At times I chose them rather than the actual roads.

I finally had to settle for some commercially minded Pygmies who had a tourist trap set up halfway to Stanleyville. I bargained for a few minutes with them and then realized they weren’t the kind of Pygmies I was looking for. They did, however, direct me to a place where I could find another American. Although talking to these people was difficult, I did understand that the American was a doctor. He lived in Albertville a couple hundred miles south of my intended destination. Since I had no pressing business in Stanleyville, I planned to visit this doctor.

1 headed south, making good time due to improved roads, and some were even paved. By nightfall, I was halfway there and very tired. Although the ride was smoother than usual, my bones ached, and I was saddle sore.

Upon reaching Albertville, I checked into a hotel and slept for the better part of a day. Then, when I was thoroughly rested, I went in search of the doctor.

I learned that the doctor was a medical missionary who owned an airplane. After finally locating him, I introduced myself as Jim Parks, The Explorer. He was glad to hear of my exploits in Africa and said he wished more people would travel around the Congo.

When I asked about his flying, I was told that he used the plane to go to far-off villages to treat sick natives. Later, he invited me to accompany him on one of his treks. Hearing this I jumped for joy.

Two days afterward we departed for a Pygmy village. As we flew I beheld the vast, green land spreading for miles under us. I could see green and brown rivers winding through tropical forest of dark green with little spots of life moving along the road.

We landed with a jarring series of bounces and vibrations in a cleared field sufficient for only the smallest planes. Pulling to a stop, we were instantly surrounded by children running and screaming from the edge of the field. When we stepped out of the plane, I saw that the children were rather well developed and the males had long whiskers on their chins. It turned out that these were genuine Pygmy adults, a race of midgets, who are reputed to be brave and deadly warriors.

The village was small and the grass and mud huts were crawling with insects. These people needed help and their sick regard this man as a god sent to save them.

Soon he set to work as a long line of patients had already formed. I was greeted as a friend since I came with the doctor. Normally the Pygmies don’t allow visitors, especially white ones.

We left for another village in a few hours and on arrival the same thing happened, the warm greeting and a long line of sick natives. I tried to talk to the natives about their problems, but I could not come close to attaining the understanding this medicine man had with these people.

We flew everyday and he treated sick natives devotedly as he had for years. We often discussed the America he had nearly forgotten and the Africa to which he had dedicated his life. During my stay we visited over 35 villages and tribes of Pygmies and Bantus.

The Bantu tribe inhabits much of Central Africa, the Congo, and as far south as Zambia. They are a colorful people who wear large feather headdresses and strings of animal teeth. Both tribes use spears and blow guns as weapons. The Pygmies are extremely accurate with their blow-guns and can send the poisoned darts through the air with great speed with a range of 50 feet. And because of his small size, the Pygmy has become a master of ambush.

After 11 days with this humanitarian I said goodby to the “doctor who flies.” Next stop: Zambia.

I traveled south across many rivers and through humid jungles where insects constantly nibbled at my skin. A big problem was the insects that splattered themselves on my face plate and windshield. I could only ride for a few hours before I had to stop and clean the mess off so I could see. I crossed the Congo River and could see men paddling long, narrow boats loaded with cargo for trading.

I entered Zambia with no problem, only warnings to be watchful for terrorists operating in the area. I reached Lusaka late that afternoon and was greeted with a hostile demonstration by young blacks against the white people. I realized

I realized that the disturbance was mainly anti-European but chose not to invite more trouble by riding through town. I went to the outskirts of the city to a hotel and spent a few days planning my next move. I decided to visit Salisbury again.

I made good time and tried to retrace some of the roads I had traveled before. Once in Salisbury, I learned from a travel agency that a ship was leaving Durban, South Africa, on Lriday, bound for Spain! I immediately booked passage, jumped on my bike, and left the city like a tornado.

This would be an endurance run for the bike and me. The trip is 1200 miles from Salisbury to Durban. At speeds of 80 mph and stops only for fuel, I reached Durban in 17 hours!

The bike underwent terrific punishment as we sailed over rocks, sand, and jarring dips in the road. When I reached Durban, the tires were badly chewed up by the road and I was exhausted.

However, I did not rest until the bike was loaded on board and I was snug in my cabin. We left Durban only a few hours after my arrival, headed for Cape Town and then on to Spain.

As soon as we docked at Cape Town I went ashore and called Barbara. We then met for lunch and planned to sail to Spain together.

It was a wonderful trip up the coast of Africa. We rounded Cape Palmas and docked at Lreetown, Sierra Leone. Crossing Cape Blanc and into the Tropic of Cancer, we entered a new and unfamiliar Africa.

The ship stopped at Rabat, Morocco, a city heavy in Moslem architecture and Arab custom. After visiting the crowded bazzars of the market place only briefly, my new traveling companion and I set sail for Barcelona, Spain. We passed through the Pillars of Hercules, unromantically known as the Straits of Gibraltar. Now in the Mediterranean Sea, we landed at the magnificent port of Barcelona.

(Continued on page 94)

Continued from page 76

Once on the road, Barbara and I traveled north along the Mediterranean seaboard. She perched behind me on a sleeping bag and waved at people as we zoomed past on our way to France. We crossed into France that evening and spent the night at Perpignan, slightly inland from the sea.

The highway along the coast was very modern and easy to navigate. The area resembled California in that the people were friendly and carefree, and the buildings were, for the most part, new. But the villages were close together and the highway always went through town. This meant we would have to slow down considerably when passing through them. We averaged about six hours of travel a day, and about 600 miles a day.

We took our time going along the Riviera. Passing through the resort area of St. Tropez Barbara tapped me on the shoulder and pointed to a New Jersey license plate. I caught up with the car and followed it to a store. The driver was an elderly man, in his seventies at least. After we introduced ourselves, he smiled and gave us his address with an invitation to visit him. That afternoon we sought out his house and were directed to an expensive looking apartment on the outskirts of town. The balcony hung over a cliff and looked down on a golden beach littered with bikini-clad girls and dark brown men wearing modified “G” strings.

While we lounged in his spacious den, he told us about his home in New Jersey and his hobbies, which included motorcycle racing. As we sat stunned he casually explained that he had given up motorcycles recently as he was now getting on in years. Next he pointed out a picture of himself skiing behind his racing boat. Needless to say we were amazed.

We stayed a few days with the elderly athlete during which we witnessed a boat race he had entered. The greyhaired sportster managed to place fourth in a roaring, spraying, bouncing race around the bay.

But we had to move on and bid our host farewell. Turning northeast, we headed toward the Rhone River Valley. We spent a day in Avignon, a large but quaint and typically French town on the River. Continuing north along the river, we came to Lyons, a city famous as a historical landmark from the time of Joan of Arc to Charles De Gaulle.

From Lyons we headed northeast to Geneva, Switzerland. The roads got steeper and the trees thinned out. This was beautiful country full of beautiful people.

We took the road to Lausanne between the border and Lake of Geneva. It became so steep we had to grind up many hills in first gear doing 5 mph. The road was paved in places, but there was only a small railing between us and a plummeting fall through the mist to the rocks below.

Lausanne spread along the shore of the Lake of Geneva and was on fairly level terrain. However, once out of the city and headed toward Paris we again started the ascent. After a long climb, the engine screaming in first and second gear, we crossed into France and decended. Across the Doubs River we headed northeast.

The highway that passed through villages was only a foot or so from the front doors of the houses. As we traveled through one town a lady opened the door to her house and nearly sent us into the wall on the other side of the street as I swerved to avoid hitting the door. The road also passed through vineyards where men and women worked in the waist high vines. We stopped at the house of the foreman of one vineyard and chatted for awhile. He offered us some of his vin rose that he claimed was the best in the valley. After gracious compliments on his wine, we continued toward the famous capital.

When we reached the town of Sens, we followed the Yonne River to Paris. Before entering the city itself, we visited a beautiful park called Le Bois (the forest). Nannies strolled slowly about the walk with their children in carts or tagging along behind. Boys romped through the park with their dogs, dashing between the tall trees that make Le Bois famous.

We stayed at a sector of Paris called kol d’ or. The first thing after our huge lprich on the Champs Elysee, we found the Kawasaki agency and asked about the local motorcycle scene.

He showed us to his workshop in which stood four new Kawasaki Mach III motorcycles. He then explained he was preparing for the Bol d’Or 24 hour endurance race. I offered my services as a mechanic, and told him I had had some experience with the Mach III in Africa. We set to work immediately.

At the track, tension was high and everyone was busy with last minute preparations and checking out the competition. Every major bike manufacturer in the world was represented.

In the first roaring hour of the race one of our bikes broke the track lap record previously held by a 500-cc Manx Norton while the torturous threemile lap required hourly pit stops.

Turning 70 mph on the curves and over a 100 mph on the straights, our No. 1 man was closely pursued by a Honda Four. During the 22nd hour, the Honda took the lead. Our hearts stopped and we yelled at the top of our lungs.

Two hours later the Honda streaked across the line under the checkered flag. Following on his tail were Mach Ills in 2nd, 3rd, and 4th places. When the race was over, the crazy fans ran onto the track to congratulate the happy Honda, not noticing that other bikes were still coming down the track to finish. As a result, spectators and contestants went flying everywhere, and several bikes were laid down at 70 mph.

While in Paris, I also tried to get a visa to go to Russia. The answer was me: “yes,” motorcycle: “no.” They told me I couldn’t carry enough gas to travel. I explained I could carry 600 miles worth of fuel. Then they told me the real reason. It seems the Russians couldn’t keep track of a bike as easily as a car. I left the Russian consulate in a huff and did what I do best: I had dinner.

We left Paris and headed for Amsterdam, Netherlands. In Amsterdam we met two American college students riding a BMW. They were touring Europe by bike.

In one market place the four of us ran into a problem when we asked for a large piece of cheese. Some words were said wrong and the shop keeper turned bright red and things got worse when we tried to clarify the statement. He ended the conversation by asking us to leave.

We rode to Bremen, Germany, with the two college boys, then on to Hamburg by ourselves. The trip was very enjoyable and the roads made fast travel easy and safe.

It was only a short hop from Hamburg to Copenhagen, Denmark. Here we toured the spendid Rosenburg Palace which dates back to 1606. Denmark, we discovered, is rich in a noble heritage and Copenhagen itself is the show place for the national treasures of history. A city of well over a million people, it comprises more than a quarter of the entire population of Denmark. On the outskirts of the capital are colorful farms, that are not large or extremely fertile, but due to exacting care and maintenance are very productive.

The Danes, unlike the Germans, greeted the story of my trip with uplifted glasses of malt liquor. I found out that the Danish consume about 16 gallons of alcholic beverages per person each year.

Next, we took the ferry to Sweden and then headed north to Stockholm. Sweden is a fabulous country. The scenery is fantastic and the weather is hearty and invigorating, but the nation has its problems with unemployment and overpopulation in the cities. The Swedish people, however, are very friendly and warm to Americans and do not let their problems affect their hos pitality.

By talking to young couples in Stockholm and elsewhere, I learned about the new custom of living together for a while before marriage. It’s not that the people are immoral, it’s just that there is such a shortage of housing in the city that young people have to live together to have an apartment away from home. Since the couple plans to marry anyway, they figure they might as well see if it will work out before it’s too late.

After a few weeks in Sweden, we headed south to Denmark. From Denmark we sailed to Scotland, land of misty hills and black lagoons. The Scots are a friendly but wary people who enjoy hunting, fishing, and drinking. I found many motorcycle events taking place on the grueling terrain of the highlands.

We traveled south through breathtaking hills rolling in green grass and thick woods. An occasional castle loomed on distant hill tops through grey mist or cool rain. We truly enjoyed the warm taverns that welcomed us after a hard day on the road. After we passed through the industrial town of Manchester and the industrial city of Birmingham, we were on our way to London.

Upon arrival, we were greeted by Mike Hailwood, four times world champion road racer. Barb and I stayed at his home in London and went to one of his last races as a professional. The race took place at Mallory Park, and the crowds greeted his arrival at the tracks as if he were the king. Barbara and I signed autographs just because we were his friends.

As you may have guessed by now, Barbara and I had fallen in love quite some time ago and decided that it was about time to tie the knot. So in a quiet little church in Hammersmith we were married on October 7, 1969. We left the red brick church on the motorcycle as the pleasantly puzzled minister waved to us from the steps.

Barbara had trouble getting her passport and visa for the USA so I arranged to send for her once I was in the States. I left for Portsmouth, England, where I boarded the luxurious S.S. France for the trip to New York.

When I cleared New York I headed for beautiful downtown Burbank, California, with 43,000 miles on the speedometer.

In Mississippi I met two guys riding brand new Harley XLCHs. They were headed for Los Angeles, so I asked if I could tag along. They said it was OK as long as I didn’t slow them down.

We covered the 3,200 miles in four days and I was home again. Barbara arrived a few weeks later and we set up our new life together. [Ö]