HELPLESSLY HOOKED

The Story Of A Sidecar Coterie: A Little More Back-Slapping, A Little Less Clashing Of Personalities.

GREG STOTT

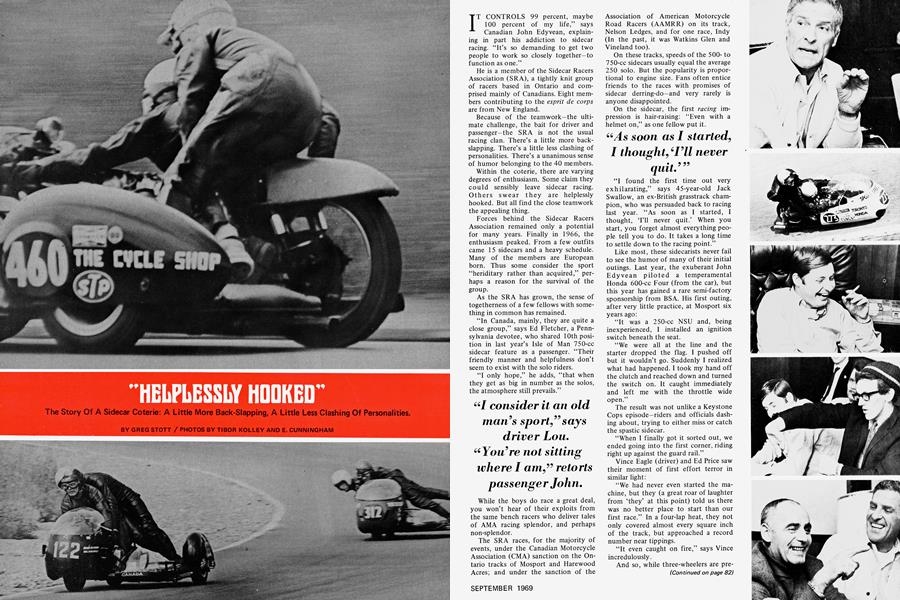

IT CONTROLS 99 percent, maybe 100 percent of my life,” says Canadian John Edyvean, explaining in part his addiction to sidecar racing. “It’s so demanding to get two people to work so closely together—to function as one.”

He is a member of the Sidecar Racers Association (SRA), a tightly knit group of racers based in Ontario and comprised mainly of Canadians. Eight members contributing to the esprit de corps are from New England.

Because of the teamwork—the ultimate challenge, the bait for driver and passenger—the SRA is not the usual racing clan. There’s a little more backslapping. There’s a little less clashing of personalities. There’s a unanimous sense of humor belonging to the 40 members.

Within the coterie, there are varying degrees of enthusiasm. Some claim they could sensibly leave sidecar racing. Others swear they are helplessly hooked. But all find the close teamwork the appealing thing.

Forces behind the Sidecar Racers Association remained only a potential for many years. Finally in 1966, the enthusiasm peaked. From a few outfits came 15 sidecars and a heavy schedule. Many of the members are European born. Thus some consider the sport “heriditary rather than acquired,” perhaps a reason for the survival of the group.

As the SRA has grown, the sense of togetherness of a few fellows with something in common has remained.

“In Canada, mainly, they are quite a close group,” says Ed Fletcher, a Pennsylvania devotee, who shared 10th position in last year’s Isle of Man 750-cc sidecar feature as a passenger. “Their friendly manner and helpfulness don’t seem to exist with the solo riders.

“I only hope,” he adds, “that when they get as big in number as the solos, the atmosphere still prevails.”

“I consider it an old man’s sport,”says driver Lou.

“You’re not sitting where I am,” retorts passenge r John.

While the boys do race a great deal, you won’t hear of their exploits from the same bench racers who deliver tales of AMA racing splendor, and perhaps non-splendor.

The SRA races, for the majority of events, under the Canadian Motorcycle Association (CMA) sanction on the Ontario tracks of Mosport and Harewood Acres; and under the sanction of the

Association of American Motorcycle Road Racers (AAMRR) on its track, Nelson Ledges, and for one race, Indy (In the past, it was Watkins Glen and Vineland too).

On these tracks, speeds of the 500to 750-cc sidecars usually equal the average 250 solo. But the popularity is proportional to engine size. Fans often entice friends to the races with promises of sidecar derring-do—and very rarely is anyone disappointed.

On the sidecar, the first racing impression is hair-raising: “Even with a helmet on,” as one fellow put it.

“As soon as I started, I thought, ‘I’ll never quit.

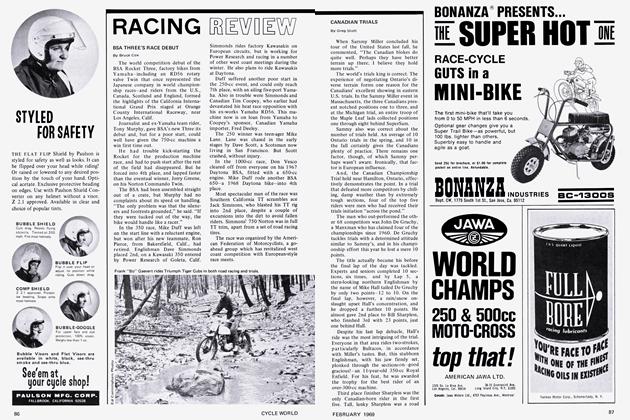

“I found the first time out very exhilarating,” says 45-year-old Jack Swallow, an ex-British grasstrack champion, who was persuaded back to racing last year. “As soon as I started, I thought, ‘I’ll never quit.’ When you start, you forget almost everything people tell you to do. It takes a long time to settle down to the racing point.”

Like most, these sidecarists never fail to see the humor of many of their initial outings. Last year, the exuberant John Edyvean piloted a temperamental Honda 600-cc Four (from the car), but this year has gained a rare semi-factory sponsorship from BSA. His first outing, after very little practice, at Mosport six years ago:

“It was a 250-cc NSU and, being inexperienced, I installed an ignition switch beneath the seat.

“We were all at the line and the starter dropped the flag. I pushed off but it wouldn’t go. Suddenly I realized what had happened. I took my hand off the clutch and reached down and turned the switch on. It caught immediately and left me with the throttle wide open.”

The result was not unlike a Keystone Cops episode—riders and officials dashing about, trying to either miss or catch the spastic sidecar.

“When I finally got it sorted out, we ended going into the first corner, riding right up against the guard rail.”

Vince Eagle (driver) and Ed Price saw their moment of first effort terror in similar light:

“We had never even started the machine, but they (a great roar of laughter from ‘they’ at this point) told us there was no better place to start than our first race.” In a four-lap heat, they not only covered almost every square inch of the track, but approached a record number near tippings.

“It even caught on fire,” says Vince incredulously.

And so, while three-wheelers are pre-

(Continued on page 82)

Continued from page 81

cisely that, their handling does require great skill and discretion. In fact, it has been suggested-not, surprisingly, by the survivors of the above incidents—that the sidecar is an elementary misconstruction.

The reason is its asymetrical design. The center line of gravity is actually off-center; power application is onesided; and one wheel steers, and that is not central. Also, braking forces are unequal.

Consequently, the outfit grabs toward the chair side when the power is on, and away from it during braking. Only when the throttle is stationary does the front wheel remain pointed straight ahead.

In the SRA, most machines have adopted the British left-hand chair. With this setup, the machines are at an advantage on the standard clockwise circuits, as an outfit with a left-hand chair corners better on a right-hand bend. The exceptions are Hugo Wolters and Henri Baumgartel, two Maryland competitors, with their newly acquired BMW special; and two first-time competitors, Paul Lewis and Bucky Riley of New Hampshire, riding Wolters’ previous BMW. Both outfits have right-hand (Continental) chairs, and of the Wolters-Baumgartel rig, great things are expected. All but the engine, which is Amol Precision built and tuned, belonged to Georg Auerbacher, a world champion rider.

“I thought they were the most ridiculous things I had ever ridden.”

On a left-hand bend, the passenger extends himself only as far as necessary for stability. He considers the wind resistance of a fully stretched out body but remembers also the centrifugal force acting on the machine. If he moves in, the chair comes up, quickly., to a point of no return.

Since the passenger resents any threat of being catapulted, the nightmarish hanging out proves quite essential. Scuffed helmets and the worn hip and shoulder areas of the leather suits are necessities, rather than marks of an eccentric acrobat.

If you find the passenger position confusing, then remember that the passenger’s head points in the direction of the turn.

Club Chairman Bill Malin, who began his career in the remote World War II atmosphere of Egypt with such exotic racing cliques as the Tel Cabur Tigers and the Suez Pirates, recalls his first

left-hand corner—without a passenger.

“L negotiated two or three righthanders without much problem. On the first left-hander, the chair wheel came up and instead of opening the throttle, I shut her down. The chair wheel came up and up till eventually I dropped a leg out. I thought they were the most ridiculous things I had ever ridden.”

A Sidecarist contemplates a broken marriage: “Racing had a great deal to do with it.”

On the right-hand bend, power is applied to the vertex of the corner, enough to keep the rear wheel slightly broken loose to induce drift, which is essential on any corner. Then it is slammed on for a hasty exit. The passenger at the same time moves his weight behind the driver for traction, particularly to keep the rear wheel down. It’s possible for the outfit to flip in a forward direction if the rear wheel gets up.

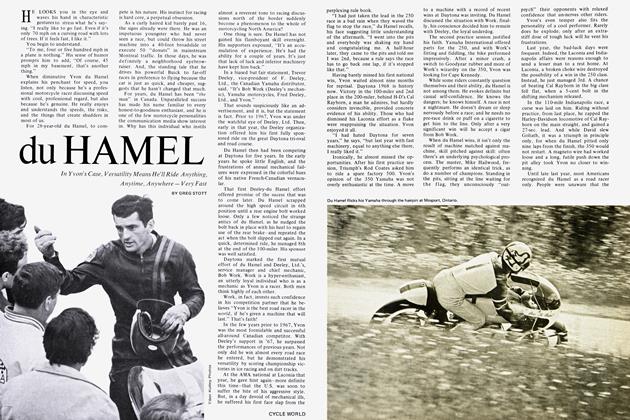

For three years, king of the sidecar class has been Lou Hermann. The reigning Canadian champion began in ’62 to transfer his fidelity from stock cars to sidecars after watching what looked to him to be a relatively easy sport.

Last year he accumulated more than 90 percent of the wins and, according to the record, it was not the time for a champion to be considering abandoning the sport. But Lou’s close friend and talented passenger, Klaus Grundier of New York, fell victim to a risk of the sport and a farewell seemed inevitable.

During a wet, greasy Mosport practice in June, the sidecars warmed up. No one, including Klaus, knows exactly what happened. The guess is that Lou shifted on the slick surface just as Klaus changed hold on the hand grips. The outfit probably twitched slightly, sending Klaus off the chair.

He suffered paralysis. Lou was distressed to the point of quitting. The impact on the group was solid. But Klaus, from the hospital, objectively reasoned the freakishness of the accident. The fellows, and particularly John Davis, his passenger-to-be, persuaded their cohort back.

Davis, 37, an accomplished soloist and what Lou simply calls, “a very good passenger,” says: “It shook everybody up, especially Lou. I remember him trying to talk me out of the chair, because I am married with children.

“I told him, ‘So are most of the fellows.’ I know my responsibilities and what can happen.”

(Continued on page 84)

Continued from page 82

The pragmatic attitude is typical of the SRA. Most maintain that despite the many trips to the boondocks, a sidecar is safer than a solo.

“I consider it an old man’s sport really,” grins Lou Hermann, but he reminds the listenerthat he’s a driver and has passengered only once and found it very frightening. “As a driver, you can afford two mistakes in a sidecar and get away with it. So I feel it’s safer. But it might not be from the passenger’s standpoint.”

Davis agrees: “You’re not sitting where I am.”

Racing in the English wet strikes a sour note in some. Edyvean, remembering an occasion where he lost his passenger for a few minutes, deplores the thought. “If it rains hard, I’ll park my bike.” And he stood by his threat earlier this year, but one of the club seniors, Jack Swallow, shrugs it off saying, “You just get wet. I’ll stay out there.”

Pre-race strategy between driver and passenger is apparent. In the first stages of racing, it is vital, but eventually a sort of mutual clairvoyance and digestion of experience from past races takes over.

“Then,” grins Lou Hermann, “You can discuss what you can do to the other fellows.”

“Yes,” adds his equally sinister partner, “like put ’em in the weeds or throw glass under their wheels.”

On certain aspects of stratagem and racing, there is a healthy divergence of point of view. Some SRA members suggest a study of the track before a race; others oppose the walk around. One fellow says, “It’s the most deceiving thing I ever did.”

One thing they all agree on is perfect timing and coordination between driver and passenger, and Ed Price gives one reason why: “In the chair it’s very important to know when your partner is going to change gears. Between certain corners, I’ll switch without holding on to anything. I take a jump, but, any sudden lurch could cause trouble.”

When the stretch between corners is so brief, the experts advise “using your toe-nails.”

Ian Payne, who made his bid with Edyvean for two years, wasn’t able to follow the advice in one of last year’s races. John changed gears as the outfit moved through a small puddle. The rig twitched, and Ian, helpless in one of those moments of no-hold, bounded off, almost being picked up by the next chair.

John traveled through the next righthander and was almost midway on the front straight before he realized that his slim, bespectacled left-hand man was not on board. They reunited shortly after for further moments of glory.

Throughout the race, the passenger is not only expected to act as a human balast—but to function also as mechanic-on-board, generally acting without instruction.

Blair Boyce, who joined late last year as Bill Malin’s passenger, undoubtedly feels more a seasoned veteran after his mechanical ordeals as passenger.

“I recall many times getting a decent sized jolt through the coils while trying to put the leads back on. And at Laconia, I had oil all over me after an oil line came off.”

On the topic of mechanicing, Ed Price said, “The biggest mistake I ever made was a day when I tried to stop a foaming oil tank by tightening the cap. Suddenly my hand was covered in oil and we were rapidly heading into a corner.

“Believe me,” he says, “I had to do some quick cleaning before clutching the grab bar.”

The race champion, Hermann, seems to have earned the award as strangetimes-with-a-passenger champion, too.

With his ex-passenger, Klaus Zans (who retired recently), he once managed an entire race at Vineland with Klaus holding a broken sidecar connection and the bike together.

At their first Vineland session, Klaus demonstrated his worth as a driver by driving the outfit home to 2nd place with Lou injured on the chair, after they flipped on the last lap.

One fellow considered the liability of playing passenger too great, and after one of those straight off the track episodes, departed, never, except for a hasty goodby, to be heard from again.

It is tacitly understood that when things do look uncertain, the passenger stays with the machine right until the last moment. A sidecar without its passenger is unmanageable at speed.

“Women passengers? If you run into the boondocks, you might never come out..

In most instances in the SRA, the financial onus is on the driver. He owns the machines, or at least invests the greater amount of money. Because frames and engines take a severe beating-more than a solo because of the asymetry and additional weightmaintenance costs are high. Tuning for reliability, rather than sheer power, is sensible but often unheeded advice.

Because the pyschics of the sidecar present such a forbidding image, the men feel their wives worry more than those of solo riders.

The point of sidecar addiction clouding responsibility was made by one racer as he reflected on his broken first marriage: “It didn’t work. I think that [racing] had a great deal to do with it.

“Now,” he beams, “my wife is with me all the way. She even wants to passenger.”

One long-time racer remarks frankly, “You say ‘don’t worry’, then you do what you want. You don’t really think about what’s happening behind you.”

Discussing the possibility of female passengers, the boys accept that some women may be able to perform well in racing, but their back-handed comments (“If you run into the boondocks, you might never come out,” or, “After you, 1 dear”) indicate they’re not going to petition the cause.

At one time, unreliability and want of data might have been excuses for the lack of inertia in sidecar progress. Today, popularity of the sport has increased fourfold through solid organization. Many of the SRA members feel the potential of the sidecar has not even been tapped. Under professional, bigdollar guidance, they feel it could sweep the country.

The means of such promotion appears to be the AMA. The sanctioning AAMRR and AMA are the difference between nothing and a heavy racing schedule—and the group counts its blessings. But both associations operate on slight budgets.

“We’d like to get into the AMA,” admits Hermann. “They draw the crowds and use the right kind of advertising.”

All agree it would be worthwhile but...

All outfits running presently conform to Federation Internationale Motocycliste (FIM) norms. The CMA and the “Alphabet Association” of course adopt the FIM standards. The AMA doesn’t.

“The rules are incompromisable,” says one fellow. “They have been standing for at least eight or nine years and call for 16-inch wheels and peculiar dimensions.

“It’s not that we lack individuality, but the FIM rules are the quick way to get ’round... 16-inch wheels (for road racing, not dirt work, as seen in California) are as passe as the Model T.”

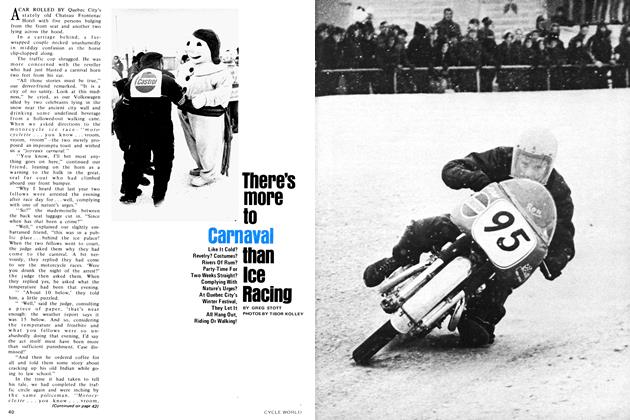

By some deliberate loopholing, the fellows have managed one AMA event, Laconia last year. Performing in a “demonstration race,” six outfits scrambled and drifted the demanding circuit, paying particular attention to the banked bends. Their general consensus is that Mosport is more enjoyable, but Laconia more difficult.

“You’ve really got to have your wits about you to do a quick time on that circuit,” they say. “You make it or break it with a good passenger. He’s never still for more than 20 seconds.”

Gerry Malin, brother of Bill, said one corner is so well banked “It was the first time our chair wheel ever left the ground on a right-hander...Peculiar!”

And so the challenge hangs over their heads—to ride the track, know its surface like a window peeper knows his toe holds, and show the crowds some of the damndest racing they’ve ever seen.

“I can see it now,” grins Lou Hermann. “We’ll overcome the politics and on the day of the first AMA national I’ll pull a repeat performance of an incident that happened at Watkins Glen a few years ago.

“There was a very sharp right-hander and I came up to the corner much too fast. I decided I would be better off going off into the grass. “We stopped right in front of the crowded grandstand,” he recalls. “Neither myself nor my passenger were hurt and when we received a tremendous hand from the spectators, I was very pleased. I thought they had admired how well I had handled the machine through the dirt so I stood up and took a little bow.

“Minutes later as we pushed the machine into the pits I noticed everyone smiling so I asked what was so funny.”

“Well,” one fellow replied, “just as you started that corner the announcer said, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, here comes the Canadian champion. Watch his superb cornering technique.’ ”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

September 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

September 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

September 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1969 -

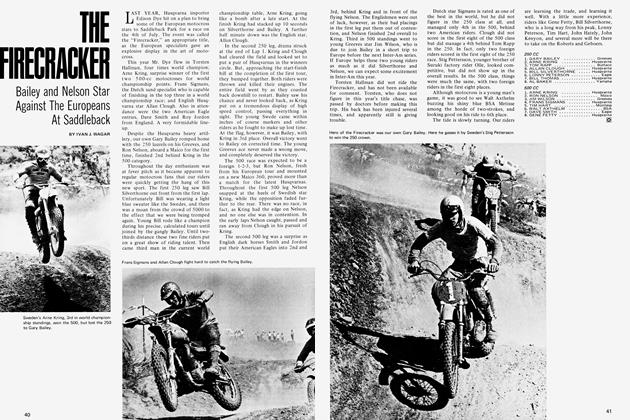

Competition

CompetitionThe Firecracker

September 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

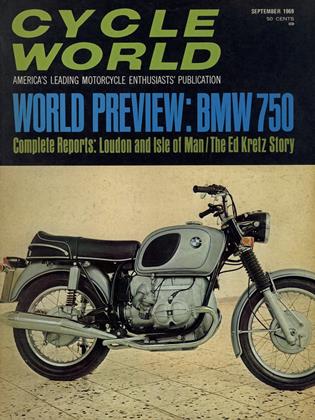

Preview

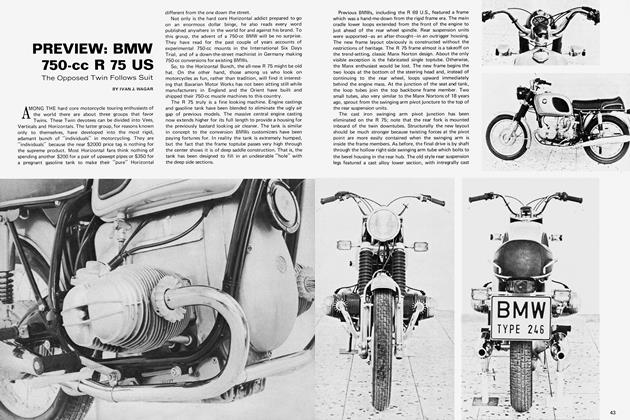

PreviewBmw 750-Cc R 75 Us

September 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar